The Social and Topographic Evolution of Medieval Anstey 35

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROTHLEY MEADOW | ROTHLEY William Davis

William Davis ROTHLEY MEADOW | ROTHLEY William Davis Est. 1935 We’ve been building beautiful new home easier. Whether you’d like to know more about the local area of our latest development, or are being held back by homes for more than 80 years. the buyer of your current home, with our expert consultants and tailored buying options we’ll support you every step of the way. And throughout that time the work of our family-owned All of this makes up our William Davis Difference. From start to company has always been underpinned by strong values, finish, when you buy from William Davis you can always expect understanding, and a commitment to being a developer to find the highest standards, stay well informed, and be treated with a difference. with consideration. That's why, in the annual Home Builders You’ll see this in everything from our unique sale packages and Federation survey, we've been rated a five-star developer four upgrades to the fine details we add to make each house a home. years in a row. But most of all, you’ll see it in our service. Having spent all In this brochure you’ll find out more about the way we work these years really getting to know our customers, we know it’s and what we do, and discover that a William Davis home offers important that we do everything we can to make finding your comfort, craftsmanship, and security – from our family, to yours. “ This is our second William Davis home in a row. -

Geography: Example Erosion

The Physical and Human Causes of Erosion The Holderness Coast By The British Geographer Situation The Holderness coast is located on the east coast of England and is part of the East Riding of Yorkshire; a lowland agricultural region of England that lies between the chalk hills of the Wolds and the North Sea. Figure 1 The Holderness Coast is one of Europe's fastest eroding coastlines. The average annual rate of erosion is around 2 metres per year but in some sections of the coast, rates of loss are as high as 10 metres per year. The reason for such high rates of coastal erosion can be attributed to both physical and human causes. Physical Causes The main reason for coastal erosion at Holderness is geological. The bedrock is made up of till. This material was deposited by glaciers around 12,000 years ago and is unconsolidated. It is made up of mixture of bulldozed clays and erratics, which are loose rocks of varying type. This boulder clay sits on layer of seaward sloping chalk. The geology and topography of the coastal plain and chalk hills can be seen in figure 2. Figure 2 The boulder clay with erratics can be seen in figure 3. As we can see in figures 2 and 3, the Holderness Coast is a lowland coastal plain deposited by glaciers. The boulder clay is experiencing more rapid rates of erosion compared to the chalk. An outcrop of chalk can be seen to the north and forms the headland, Flamborough Head. The section of coastline is a 60 kilometre stretch from Flamborough Head in the north to Spurn Point in the south. -

Final Thesis.Pdf

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. Kersey, H. (2017) Aristocratic female inheritance and property holding in thirteenth-century England. Ph.D. thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University. Contact: [email protected] ARISTOCRATIC FEMALE INHERITANCE AND PROPERTY HOLDING IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND By Harriet Lily Kersey Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 ii Abstract This thesis explores aristocratic female inheritance and property holding in the thirteenth century, a relatively neglected topic within existing scholarship. Using the heiresses of the earldoms and honours of Chester, Pembroke, Leicester and Winchester as case studies, this thesis sheds light on the processes of female inheritance and the effects of coparceny in a turbulent period of English history. The lives of the heiresses featured in this thesis span the reigns of three English kings: John, Henry III and Edward I. The reigns of John and Henry saw bitter civil wars, whilst Edward’s was plagued with expensive foreign wars. -

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review September 2020 2 Contents Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review .......................................................... 1 August 2020 .............................................................................................................. 1 Role of this Evidence Base study .......................................................................... 6 Evidence Base Overview ................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 7 General Description of Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge........................... 7 Figure 1: Map showing the extent of the Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge 8 2. Policy background ....................................................................................... 9 Formulation of the Green Wedge ....................................................................... 9 Policy context .................................................................................................... 9 National Planning Policy Framework (2019) ...................................................... 9 Core Strategy (December 2009) ...................................................................... 10 Site Allocations and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document (2016) ............................................................................................. 10 Landscape Character Assessment (September 2017) .................................... -

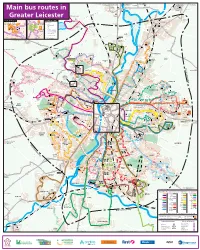

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Leicestershire County Council Highway Forum for Charnwood

QRUrlQRUrl LEICESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL HIGHWAY FORUM FOR CHARNWOOD WEDNESDAY, 1 JULY 2015 AT 4.30 PM TO BE HELD AT COMMITTEE ROOM 2, CHARNWOOD BOROUGH COUNCIL OFFICES AGENDA Item 1. Chairman's welcome 2. Apologies for absence 3. Any other items which the Chairman has decided to take as urgent elsewhere on the agenda 4. Declarations of interest in respect of items on the Agenda 5. Minutes of the previous meeting (Pages 5 - 14) 6. Chairman's update 7. Presentation of petitions under Standing Order 36 A petition with 113 signatures from District Councillor Seaton will be presented. The petition requests safeguards to make the railway bridge along Church Hill Road, Thurmaston safer for pedestrians. ‘We the undersigned request action from the Leicestershire County Council Highways Authority regarding pedestrian safety under the railway bridge on Church Hill Road, Thurmaston Leicester. Church Hill bridge is the only pedestrian route to Thurmaston’s three Primary schools from east of Thurmaston. The bridge is only wide enough for single vehicle movement and the footpath to one side of the bridge is narrow. The narrowness of the road means that vans and small lorries take Officer to Contact: Sue Dann, Democratic Support ◦ Department of Environment and Transport ◦ Leicestershire County Council ◦ County Hall Glenfield ◦ Leicestershire ◦ LE3 8RJ ◦ Tel: 0116 305 7122 ◦ Email: [email protected] www.twitter.com/leicsdemocracy www.facebook.com/leicsdemocracy www.leics.gov.uk/local_democracy up the whole width affecting their wing mirrors to protrude onto the path causing pedestrian to press against the filthy walls of the bridge. The narrowness of the path means that pedestrians have no option but to walk in single file. -

Magazine July/August 2018

ISSUE NUMBER 156 CONTENTS Church News 3, 20/22 All Saints Garden Party 6/7 & 33 Coffee & Cake 5 Tennis Club Lesson 7 Scarecrow Festival 8 From the Park 10/14 Newtown Brownies 16 Open Gardens 17 Good Neighbours 18 Bob Bown Playing Field 19 Gardening Club 24 Margaret Clifford 27 From the Records 28 Boules 30 Neighbourhood Watch 31/33 Rainbows 34 Parish Council 36/37 July/August 2018 1 Need a Helping Hand? Domestic, Commer- Fed up of tring to fit everything in and work? cial , Rental property & Or is it all becoming Communal area cleans a burden? Oven Cleans from £45 All cleaning products We provide included a friendly Bed Linen changed & laundered & efficient Ironing (collection & tailored service delivery service in- cluded) Call Lisa on Fully insured 0116 304 0607 or 0753 931 6717 Consult WALTER MILES (Electrical Engineers) LTD Est. 1928 For All Your Electrical Requirements LIGHTING, HEATING, POWER, REPAIRS, RENEWALS AND MAINTENANCE Member of the Electrical Contractors’ Association and N.I.C.E.I.C Office and Works Marshall House, West Street, Glenfield, LEICESTER,LE3 8DT Telephone 0116 287 2400 Fax 0116 287 2552 E-Mail [email protected] 2 The Bradgate Group Parish I grew up in North London. Some of you know that, you’ve worked out my accent isn’t local and that my support of Tottenham Hotspur can only be credited to growing up close to their home in London. My earliest memories date from the time my Dad was the Curate in a Church in Tollington Park (which actually is much closer to the old Arsenal ground at Highbury). -

26 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

26 bus time schedule & line map 26 Leicester - Groby - Ratby - Thornton - Bagworth - View In Website Mode Ellistown - Coalville The 26 bus line (Leicester - Groby - Ratby - Thornton - Bagworth - Ellistown - Coalville) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bagworth: 6:28 PM (2) Coalville: 6:12 AM - 6:12 PM (3) Leicester: 6:19 AM - 5:03 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 26 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 26 bus arriving. Direction: Bagworth 26 bus Time Schedule 18 stops Bagworth Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:28 PM Marlborough Square, Coalville Marlborough Square, England Tuesday 6:28 PM Avenue Road, Coalville Wednesday 6:28 PM 185 Belvoir Road, England Thursday 6:28 PM North Avenue, Coalville Friday 6:28 PM 182 Central Road, Hugglescote And Donington Le Heath Civil Parish Saturday 6:28 PM Fairƒeld Road, Hugglescote 78 Central Road, Hugglescote And Donington Le Heath Civil Parish Post O∆ce, Hugglescote 26 bus Info Station Road, Hugglescote Direction: Bagworth Stops: 18 The Common, Hugglescote Trip Duration: 15 min Line Summary: Marlborough Square, Coalville, Sherwood Close, Ellistown Avenue Road, Coalville, North Avenue, Coalville, Fairƒeld Road, Hugglescote, Post O∆ce, Parkers Close, Ellistown Hugglescote, Station Road, Hugglescote, The Common, Hugglescote, Sherwood Close, Ellistown, Amazon, Bardon Parkers Close, Ellistown, Amazon, Bardon, Amazon, Bardon, Parkers Close, Ellistown, Working Mens Club, Amazon, Bardon Ellistown, Primary School, Ellistown, -

127 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

127 bus time schedule & line map 127 Leicester - Loughborough - Shepshed View In Website Mode The 127 bus line (Leicester - Loughborough - Shepshed) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Leicester: 6:00 AM - 6:55 PM (2) Loughborough: 7:32 AM - 11:10 PM (3) Quorn: 10:08 PM (4) Shepshed: 5:31 AM - 10:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 127 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 127 bus arriving. Direction: Leicester 127 bus Time Schedule 78 stops Leicester Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:40 AM - 9:08 PM Monday 6:00 AM - 6:55 PM Gri∆n Close, Shepshed Gri∆n Close, Shepshed Civil Parish Tuesday 6:00 AM - 6:55 PM The Meadows, Shepshed Wednesday 6:00 AM - 6:55 PM Springƒeld Road, Shepshed Thursday 6:00 AM - 6:55 PM Friday 6:00 AM - 6:55 PM Council O∆ces, Shepshed 47a Charnwood Road, Shepshed Civil Parish Saturday 6:15 AM - 7:00 PM Bull Ring, Shepshed Bull Ring, Shepshed Civil Parish Sullington Road, Shepshed 127 bus Info Challottee, Shepshed Civil Parish Direction: Leicester Stops: 78 Leicester Road, Shepshed Trip Duration: 73 min Line Summary: Gri∆n Close, Shepshed, The Cambridge Street, Shepshed Meadows, Shepshed, Springƒeld Road, Shepshed, Council O∆ces, Shepshed, Bull Ring, Shepshed, Ingleberry Road, Shepshed Sullington Road, Shepshed, Leicester Road, Shepshed, Cambridge Street, Shepshed, Ingleberry Highways Department, Shepshed Road, Shepshed, Highways Department, Shepshed, Petrol Station, Loughborough, Pitsford Drive, Petrol Station, Loughborough Loughborough, Ravensthorpe Drive, -

Photographic Survey of Groby Conservation Area

GROBY CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL & MANAGEMENT PLAN PHOTOGRAPHIC SURVEY OF GROBY CONSERVATION AREA November 2010 1 Markfield Road sited at the junction with Ratby Road is a pleasant stone property. Unfortunately, the two dormer windows and fixed plastic shop canopies are not traditional features within the conservation area. The chimney stacks and pots are imposing features in this area of the conservation area. The terrace of four dwellings 3 – 9 Markfield Road are stone properties with slate roofs and dominant chimney stacks. Unfortunately, the gable end to no. 9 has been rendered. - 2 - 11 Markfield Road is a large rendered dwelling, painted white, with a stone plinth, slate roof and stone boundary walls. The property still has chimney stacks and pots and a front bay window has been added. 13 Markfield Road is a large imposing dwelling with two front bay windows and a fine privet hedge. The property is rendered, painted white with a slate roof and interesting diaper brickwork. - 3 - This charming thatched cottage, 15 Markfield Road, has one half of its front elevation built in stone and the other rendered. This bungalow is one of three modern dwellings that run up Markfield Road numbering 17 – 21. Unfortunately, these dwellings do not respect the traditional character of the conservation area by way of their design or use of modern materials. - 4 - The brick garage fronting 19 Markfield Road does not respect traditional character of the conservation area in its form or siting. The modern bungalow, 21 Markfield Road, does not reflect the character of the conservation area. - 5 - View looking westwards along Markfield Road showing a traditional stone wall running up the carriageway and planting on the left where a mineral railway line once crossed under the road. -

Hambleton 5/10/07 17:42 Page 1

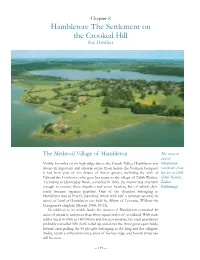

Hambleton 5/10/07 17:42 Page 1 Chapter 8 Hambleton: The Settlement on the Crooked Hill Sue Howlett The Medieval Village of Hambleton The western end of Visible for miles on its high ridge above the Gwash Valley, Hambleton was Hambleton always an important and valuable estate. Even before the Norman Conquest peninsula from it had been part of the dower of Saxon queens, including the wife of the air in 2006 Edward the Confessor, who gave her name to the village of Edith Weston. (John Nowell, According to Domesday Book, compiled in 1086, the manor was extensive Zodiac enough to contain three churches and seven hamlets, five of which after- Publishing) wards became separate parishes. One of the churches belonging to Hambleton was St Peter’s, Stamford, which with half a carucate (around 60 acres) of land at Hambleton was held by Albert of Lorraine, William the Conquerer’s chaplain (Morris 1980, 19-21). In addition to its arable lands, the manor of Hambleton contained 40 acres of meadow and more than three square miles of woodland. With male adults listed in 1086 as 140 villeins and thirteen bordars, the total population probably exceeded 500. Serfs toiled up and down the three great open fields, behind oxen pulling the 45 ploughs belonging to the king and the villagers. Today, nearly a millennium later, areas of former ridge and furrow strips can still be seen. – 149 – Hambleton 5/10/07 17:43 Page 2 An 1839 drawing of Hambleton Church (Uppingham School Archives) Some time after the Domesday survey, William the Conquerer granted Hambleton to the powerful Norman family of Umfraville, who sub-divided the large and sprawling manor into two: Great and Little Hambleton. -

Land for Sale in Cropston, Leicestershire Land on Bradgate Road, Cropston, Leicester, LE7 7HT

v6.1 01727 817479 www.vantageland.co.uk Land for Sale in Cropston, Leicestershire Land on Bradgate Road, Cropston, Leicester, LE7 7HT Investment Land for sale well situated near Thurmaston, Leicester, Loughborough, A46 and the M1 Motorway M1 A46 This site comprises of approximately 3 acres of arable land for sale with investment potential due to the adjacent housing and its prime location on the outskirts of Leicester. The land benefits from gated access and is available freehold as a whole or in 2 good sized lots that have the potential for paddock conversion. Cropston is a desirable and affluent village in Leicestershire, between Leicester to the south and Loughborough to the north. It acts as a commuter village for surrounding towns and villages. Leicester’s surrounding towns and villages are expected to benefit from the regeneration of the thriving city centre to strengthen the areas economy. The site is available freehold as a whole or in lots. Lot A: 1.40 acres SOLD Lot B: 1.51 acres SOLD Travel 1.4milestotheA46 2.2milestotheA6 3.8milestoSilebyTrainStation* 4.4milestoJunction21aoftheM1 11.1milestoEastMidlandsInternational Airport * JourneyTimes:8minstoLoughborough;15 minstoLeicester;1hr35minstoLondonSt Pancras POSTCODE OF NEAREST PROPERTY:LE77HT © COLLINS BARTHOLOMEW 2003 Location 0.8milestoThurcaston SituatedintheheartofCharnwoodForest, 1.8milestoAnstey Cropstonoffersmanycountrywalksand pursuitsandispartoftheNationalForest. 2.1milestoMountsorrel 2.9milestoBirstall LocatedwithinCharnwoodForestisBradgate Park,Leicestershire’slargestandmostpopular