The Waimumu Trust (SILNA) Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

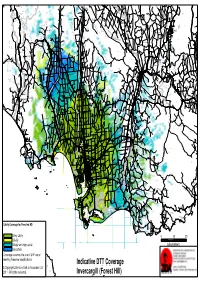

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197

SECTION 6 SCHEDULES Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197 SECTION 6: SCHEDULES SCHEDULE SUBJECT MATTER RELEVANT SECTION PAGE 6.1 Designations and Requirements 3.13 Public Works 199 6.2 Reserves 208 6.3 Rivers and Streams requiring Esplanade Mechanisms 3.7 Financial and Reserve 215 Requirements 6.4 Roading Hierarchy 3.2 Transportation 217 6.5 Design Vehicles 3.2 Transportation 221 6.6 Parking and Access Layouts 3.2 Transportation 213 6.7 Vehicle Parking Requirements 3.2 Transportation 227 6.8 Archaeological Sites 3.4 Heritage 228 6.9 Registered Historic Buildings, Places and Sites 3.4 Heritage 251 6.10 Local Historic Significance (Unregistered) 3.4 Heritage 253 6.11 Sites of Natural or Unique Significance 3.4 Heritage 254 6.12 Significant Tree and Bush Stands 3.4 Heritage 255 6.13 Significant Geological Sites and Landforms 3.4 Heritage 258 6.14 Significant Wetland and Wildlife Habitats 3.4 Heritage 274 6.15 Amalgamated with Schedule 6.14 277 6.16 Information Requirements for Resource Consent 2.2 The Planning Process 278 Applications 6.17 Guidelines for Signs 4.5 Urban Resource Area 281 6.18 Airport Approach Vectors 3.2 Transportation 283 6.19 Waterbody Speed Limits and Reserved Areas 3.5 Water 284 6.20 Reserve Development Programme 3.7 Financial and Reserve 286 Requirements 6.21 Railway Sight Lines 3.2 Transportation 287 6.22 Edendale Dairy Plant Development Concept Plan 288 6.23 Stewart Island Industrial Area Concept Plan 293 6.24 Wilding Trees Maps 295 6.25 Te Anau Residential Zone B 298 6.26 Eweburn Resource Area 301 Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 198 6.1 DESIGNATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS This Schedule cross references with Section 3.13 at Page 124 Desig. -

Waimumu Stream Drainage

tion, Mt', MoNab. WAIMUMU STREAM DRAINAGE. [LOCAL BILL.] ANALYSIS. Title. 14. Alteration of manner of election, Preamble. 15. Meetings of Board. 1. Short Title. 16. Board incorporated. 2. Constitution of district. 17. Board to have within district powers of 8. Board of Trustees. County Council. 4. First election. 18. Control of Waimumu Stream. 5. Ratepayers lists. 19. Board to have powers of Land Drainage 6. Objections. Board. 7. Appeal from list. 20 Additional powers. 8. Qualification of electors. 21. Resolution in exercise of power in Borough 9. Elections. of Mataura. 10. Subsequent elections. 22. Rates. 11. Appointment by Governor. 23. Classification of landis. 12. Election in case of vacancy. 24. Assumption of liabilities by Board. 19, Gaze#ing of eledion. Schedules. A BILL INTITULED AN Aor 00 provide for the Administration of a Tail-race or Flood- Title. channel in the Waimumu Stream constructed by the Mataura Borough Council under a Deed of Arrangement purporting to 6 be made in Pursuance of " The Mining Act, 1898," and for the Formation of a Drainage District in the District drained by the Waimumu Stream. WHEREAS by a deed dated the thirteenth day of May, one thousand preamble. nine ·hundred and two, and purporting to be made between the 10 Minister of Mines of the first part, the Corporation of the Borough of Mataura, acting by the Borough Council, of the second part, certain. landowners therein described of the third part, and certain mining companies therein described of the fourth part, after reciting that by reason of the -

Maori Cartography and the European Encounter

14 · Maori Cartography and the European Encounter PHILLIP LIONEL BARTON New Zealand (Aotearoa) was discovered and settled by subsistence strategy. The land east of the Southern Alps migrants from eastern Polynesia about one thousand and south of the Kaikoura Peninsula south to Foveaux years ago. Their descendants are known as Maori.1 As by Strait was much less heavily forested than the western far the largest landmass within Polynesia, the new envi part of the South Island and also of the North Island, ronment must have presented many challenges, requiring making travel easier. Frequent journeys gave the Maori of the Polynesian discoverers to adapt their culture and the South Island an intimate knowledge of its geography, economy to conditions different from those of their small reflected in the quality of geographical information and island tropical homelands.2 maps they provided for Europeans.4 The quick exploration of New Zealand's North and The information on Maori mapping collected and dis- South Islands was essential for survival. The immigrants required food, timber for building waka (canoes) and I thank the following people and organizations for help in preparing whare (houses), and rocks suitable for making tools and this chapter: Atholl Anderson, Canberra; Barry Brailsford, Hamilton; weapons. Argillite, chert, mata or kiripaka (flint), mata or Janet Davidson, Wellington; John Hall-Jones, Invercargill; Robyn Hope, matara or tuhua (obsidian), pounamu (nephrite or green Dunedin; Jan Kelly, Auckland; Josie Laing, Christchurch; Foss Leach, stone-a form of jade), and serpentine were widely used. Wellington; Peter Maling, Christchurch; David McDonald, Dunedin; Bruce McFadgen, Wellington; Malcolm McKinnon, Wellington; Marian Their sources were often in remote or mountainous areas, Minson, Wellington; Hilary and John Mitchell, Nelson; Roger Neich, but by the twelfth century A.D. -

Urban and Industry

The Southland Economic Project URBAN AND INDUSTRY SOUTHLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL Cover photo: Matāura looking south across the Matāura River Source: Emma Moran The Southland Economic Project: Urban and Industry Technical Report May 2018 Editing Team: Emma Moran – Senior Policy Analyst/Economist (Environment Southland) Denise McKay – Policy and Planning Administrator (Environment Southland) Sue Bennett – Principal Environmental Scientist (Stantec) Stephen West – Principal Consents Officer (Environment Southland) Karen Wilson – Senior Science Co-ordinator (Environment Southland) SRC Publication No 2018-17 Document Quality Control Environment Policy, lanning and egulatory ervices Southland Division Report reference Title: The outhland conomic roject: Urb an ndustry No: 2018-17 Emma Moran, enio olicy nalyst/Economist, nvironment outhland Denis McKay, licy d anning Administrator, nvironment outhland Prepared by Sue ennett, Principal nvironmental cientist, tantec Stephen est, Principal onsents fficer, Environment Southland Karen ilson, enio cience o-ordinator, nvironment Southland Reviewed by: Ke urray, RMA anner, Departmen f onservation Approved for issue by The overnance ro or he outhlan conomic roject Date issued ay 2018 Project Code 03220.1302 Document History Version Final Status: Final Date May 2018 Doc ID: 978-0-909073-41-1 municipal fi i thi reproduced from consultants’ outputs devel wi territorial authoriti Southl Distri Council Southl Distri Council Invercargill Ci Council l reasonabl nformati withi thi incl esti cul average concentrations over four years Disclaimer multiplied by the annual flows. This is a ‘broad brush’ calculati i may di Envi Southl accounti contami National Poli val thi i system’s existing performance (the base) and its upgrade scenarios. Citation Advice Moran, ., McKay D., Bennett, ., West, ., an Wilson, . -

South Island Fishing Regulations for 2020

Fish & Game 1 2 3 4 5 6 Check www.fishandgame.org.nz for details of regional boundaries Code of Conduct ....................................................................4 National Sports Fishing Regulations ...................................... 5 First Schedule ......................................................................... 7 1. Nelson/Marlborough .......................................................... 11 2. West Coast ........................................................................16 3. North Canterbury ............................................................. 23 4. Central South Island ......................................................... 33 5. Otago ................................................................................44 6. Southland .........................................................................54 The regulations printed in this guide booklet are subject to the Minister of Conservation’s approval. A copy of the published Anglers’ Notice in the New Zealand Gazette is available on www.fishandgame.org.nz Cover Photo: Jaymie Challis 3 Regulations CODE OF CONDUCT Please consider the rights of others and observe the anglers’ code of conduct • Always ask permission from the land occupier before crossing private property unless a Fish & Game access sign is present. • Do not park vehicles so that they obstruct gateways or cause a hazard on the road or access way. • Always use gates, stiles or other recognised access points and avoid damage to fences. • Leave everything as you found it. If a gate is open or closed leave it that way. • A farm is the owner’s livelihood and if they say no dogs, then please respect this. • When driving on riverbeds keep to marked tracks or park on the bank and walk to your fishing spot. • Never push in on a pool occupied by another angler. If you are in any doubt have a chat and work out who goes where. • However, if agreed to share the pool then always enter behind any angler already there. • Move upstream or downstream with every few casts (unless you are alone). -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No

110 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 6 SCHEDULE Puketi, Mr .J. McAtamney's Residence. Purekireki, Public Hall. A warua Electoral District Ratanui, Public Hall. Brydone, Public School. Romahapa, Public Hall. Dacre, Public School. Stirling, Public School. Edendale, Public School. Stony Creek, Mr E. King's Residence. Fortrose, Social Hall. Tahakopa, Public School. Glencoe, Waitane-Glencoe Domain Board Hall. Tahatika, Public Hall. Glenham, Public Hall. Tapariui, Public School. Gorge Road, Public School. Tarara, Public School. Haldane, Public Hall. Taumata, Public Hall. Kapuka, Public School. Tawanui, Public School. Main South Road, near Mataura, Mr L. F. Rowe'1 Garage. Te Houka, Public Hall. Mataura Island, Public School. Tokoiti, Public School. Menzies Ferry, Public School. Waikaka Valley, Public School. Mimihau, Public School. Waikoikoi, Public School. • Mokoreta, Public School. Waipahi, Public School. Morton Mains (Siding), Public School. Wairuna, Public Hall. Niagara, Public School. Waitepeka, Public School. Otara, Public School. Waiwera South, Public School. Pine Bush, Public School. Wangaloa, School Building. Progress Valley, Public School. Warepa, Public School. Quarry Hills, Public School. Wharetoa, Public Hall. Redan (Wyndham), Public School. Seaward Downs, Public School. Wallace Electoral District South Wyndham, Public School. Charlton, Public Hall. Te Tipua, Public School. Croydon Bush, Public Hall. Tokonui, Public School. .Jacobstown (Gore), Sale and Main Streets corner, Office of Tuturau, Public School. Gord,on Falconer and Company. Waikawa, Public School. Waimumu, Public School. Waikawa Valley, Mr A. W. Crosbie's Hut. -west Gore, Coutts Road, Mr .J. Laird's Residence. Waimahaka, Public School. Waituna, Public School. As witness the hand' of His Excellency the Governor-General, Wyndham, Town Hall. this 2nd day of February 1955 . -

New Zealand Touring Map

Manawatawhi / Three Kings Islands NEW ZEALAND TOURING MAP Cape Reinga Spirits North Cape (Otoa) (Te Rerengawairua) Bay Waitiki North Island Landing Great Exhibition Kilometres (km) Kilometres (km) N in e Bay Whangarei 819 624 626 285 376 450 404 698 539 593 155 297 675 170 265 360 658 294 105 413 849 921 630 211 324 600 863 561 t Westport y 1 M Wellington 195 452 584 548 380 462 145 355 334 983 533 550 660 790 363 276 277 456 148 242 352 212 649 762 71 231 Wanaka i l Karikari Peninsula e 95 Wanganui 370 434 391 222 305 74 160 252 779 327 468 454 North Island971 650 286 508 714 359 159 121 499 986 1000 186 Te Anau B e a Wairoa 380 308 252 222 296 529 118 781 329 98 456 800 479 299 348 567 187 189 299 271 917 829 Queenstown c Mangonui h Cavalli Is Themed Highways29 350 711 574 360 717 905 1121 672 113 71 10 Thames 115 205 158 454 349 347 440 107 413 115 Picton Kaitaia Kaeo 167 86 417 398 311 531 107 298 206 117 438 799 485 296 604 996 1107 737 42 Tauranga For more information visit Nelson Ahipara 1 Bay of Tauroa Point Kerikeri Islands Cape Brett Taupo 82 249 296 143 605 153 350 280 newzealand.com/int/themed-highways643 322 329 670 525 360 445 578 Mt Cook (Reef Point) 87 Russell Paihia Rotorua 331 312 225 561 107 287 234 1058 748 387 637 835 494 280 Milford Sound 11 17 Twin Coast Discovery Highway: This route begins Kaikohe Palmerston North 234 178 853 401 394 528 876 555 195 607 745 376 Invercargill Rawene 10 Whangaruru Harbour Aotearoa, 13 Kawakawa in Auckland and travels north, tracing both coasts to 12 Poor Knights New Plymouth 412 694 242 599 369 721 527 424 181 308 Haast Opononi 53 1 56 Cape Reinga and back. -

Greetings from Waimumu, the Fellowship of Christian Farmers

Greetings from Waimumu, The Fellowship of Christian Farmers, International NZ will have a stand at the Southern Field Days, February 12-14th, at the Waimumu Exhibit Field near Gore. This will be the first FCFI stand at the Southland event. Our marquee will be on lot 511 near the Gate 4 Entrance. Hopefully we will get to see some of you who live on the South Island. Others we may meet at National Fieldays in June. We need to ask you to pray for the organization of Fellowship of Christian Farmers, Int. NZ. Pray for the Lord’s wisdom as we move forward with organizational plans. The need to grow spiritually in Christ and to use our hands to grow food, fix machines and assist missionaries around the world is greater than ever. New Zealand farmers can travel anywhere in the world to serve the Lord with their passport. Recently in Central, Illinois on November 17th, an EF-4 tornado destroyed 1080 homes in Washington, IL and 20 farm yards. Farmers in FCFI have been busy helping families clean up the damage in the middle of winter. This is similar to NZ farmers organizing the “Farmy Army” in Christchurch to clean up liquifaction in the streets following earthquakes. Your feedback is important to us to know how the Lord is leading you to be part of this ministry. Special Meeting Invitation - You are invited to attend a special meeting of the Fellowship of Christian Farmers, Int. at the Mataura Christian Church, Mataura, February 16th at 7:00 pm. We will have a presentation explaining the recent projects of FCFI and a time to sing, read scripture and pray for the needs of the community. -

HEAT PLANT in NEW ZEALAND

HEAT PLANT in NEW ZEALAND Heat Plant Sized Greater Than One Hundred Kilowatts Thermal Segmented by Industry Sector as at 1st August 2011 Database updated by CRL Energy Ltd on behalf of the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority While CRL Energy Ltd has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the Heating Plant in New Zealand Database, no responsibility is accepted for any error. CRL Energy Limited Report No 11/11031 1 Contents 1. Introduction...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 2. Methodology .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 3. Survey........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 3.1 Key assumptions................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 3.2 Industry coverage..............................................................................................................................................................................................................4 -

Allicance Group Ltd Mataura

BEFORE THE SOUTHLAND REGIONAL COUNCIL IN THE MATTER OF of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER OF of an application by Alliance Group to divert water from the Mataura River for the purposes of generating electricity STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE BY JOHN KYLE 21 NOVEMBER 2018 1. INTRODUCTION My name is John Clifford Kyle. I hold an honours degree in Regional Planning from Massey University, obtained in 1987. I am the Managing Director of the firm Mitchell Daysh Limited, which practices as a planning and environmental consultancy throughout New Zealand. I have been engaged in resource and environmental management for 30 years. My experience includes a mix of local authority and consultancy resource management work. Since 1994, I have been involved with providing consultancy advice with respect to Regional and District Plans, designations, resource consents, environmental management and environmental impact assessments. This work includes extensive experience with large-scale consenting projects involving inputs from a multidisciplinary team. An outline of projects in which I have been called upon to provide resource management advice in recent times is included as Appendix A. While I accept that this is not an Environment Court hearing, I have read and agree to comply with the Environment Court’s Code of Conduct for Expert Witnesses contained in the Practice Note 2014. I confirm that the issues addressed in this brief of evidence are within my area of expertise. I have not omitted to consider material facts known to me that might alter or detract from the opinions that I express here. I participated in conferencing with two of the other planning witnesses involved in this hearing on 15 November 2018. -

Eyre Mountains/Taka Rä Haka Conservation Park

Eyre Mountains/ Taka Rä Haka Conservation Park Northern Southland CONteNTS Introduction Introduction 5 The Eyre Mountains/Taka Rä Haka Conservation Park is situated to the south west of Lake Wakatipu, between the Park Access 5 distinctive wet granite mountains of Fiordland and the classic drier schist landscape of Central Otago. Mäori named the area Taka Rä Haka O Te Rä in reference Recreation Opportunities 6 to the setting sun on the mountain tops at day’s end. The Eyre Mountains were named after the explorer Edward Important Information 9 John Eyre, Lieutenant-Governor of New Zealand (South Island and lower North Island) from 1848-. Huts and Hut Fees 10 The Eyre Mountains/Taka Rä Haka Conservation Park covers 6,160 hectares of rugged, mountainous country, Oreti Valley 11 interspersed with long, narrow river valleys and a great variety of flora and fauna, some of which are unique to Southland. The park was officially opened on 1 June 00 Windley Valley 13 by the Hon. Chris Carter, Minister of Conservation. Acton Valley 15 Park Access Cromel Valley 16 The park is approximately an hour’s drive from either Invercargill or Queenstown. Access is from a number of Irthing Valley 19 points along State Highway 6 (between Kingston and Five Rivers), the Five Rivers – Mossburn Road and from State Highway 94 (Mossburn – Te Anau Road). Note that many Eyre Creek 21 access routes into the park are on public access easements through private Upper Mataura River 23 property. Please respect local land- owners by keeping Further Information 24 to formed tracks and complying with access information posted on signs.