Climate Change, Extinction, and Sky Island Biogeography in a Montane Lizard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Kansas Biological Survey Report #151 Kelly Kindscher, Randy Jennings, William Norris, and Roland Shook September 8, 2008 Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Cover Photo: The Gila River in New Mexico. Photo by Kelly Kindscher, September 2006. Kelly Kindscher, Associate Scientist, Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, 2101 Constant Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66047, Email: [email protected] Randy Jennings, Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] William Norris, Associate Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Roland Shook, Emeritus Professor, Biology, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Citation: Kindscher, K., R. Jennings, W. Norris, and R. Shook. Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico. Open-File Report No. 151. Kansas Biological Survey, Lawrence, KS. ii + 42 pp. Abstract During 2006 and 2007 our research crews collected data on plants, vegetation, birds, reptiles, and amphibians at 49 sites along the Gila River in southwest New Mexico from upstream of the Gila Cliff Dwellings on the Middle and West Forks of the Gila to sites below the town of Red Rock, New Mexico. -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus Poinsettii

856.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus poinsettii Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Webb, R.G. 2008. Sceloporus poinsettii. Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard Crevice Spiny Lizard Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard 1852:126. Type-locality, “Rio San Pedro of the Rio Grande del Norte, and the province of Sonora,” restricted to either the southern part of the Big Burro Moun- tains or the vicinity of Santa Rita, Grant County, New Mexico by Webb (1988). Lectotype, National Figure 1. Adult male Sceloporus poinsettii poinsettii (UTEP Museum of Natural History (USNM) 2952 (subse- 8714) from the Magdalena Mountains, Socorro County, quently recataloged as USNM 292580), adult New Mexico (photo by author). male, collected by John H. Clark in company with Col. James D. Graham during his tenure with the U.S.-Mexican Boundary Commission in late Au- gust 1851 (examined by author). See Remarks. Sceloporus poinsetii: Duméril 1858:547. Lapsus. Tropidolepis poinsetti: Dugès 1869:143. Invalid emendation (see Remarks). Sceloporus torquatus Var. C.: Bocourt 1874:173. Sceloporus poinsetti: Yarrow “1882"[1883]:58. Invalid emendation. S.[celoporus] t.[orquatus] poinsettii: Cope 1885:402. Seloporus poinsettiii: Herrick, Terry, and Herrick 1899:123. Lapsus. Sceloporus torquatus poinsetti: Brown 1903:546. Sceloporus poissetti: Král 1969:187. Lapsus. Figure 2. Adult female Sceloporus poinsettii axtelli (UTEP S.[celoporus] poinssetti: Méndez-De la Cruz and Gu- 11510) from Alamo Mountain (Cornudas Mountains), tiérrez-Mayén 1991:2. Lapsus. Otero County, New Mexico (photo by author). Scelophorus poinsettii: Cloud, Mallouf, Mercado-Al- linger, Hoyt, Kenmotsu, Sanchez, and Madrid 1994:119. Lapsus. Sceloporus poinsetti aureolus: Auth, Smith, Brown, and Lintz 2000:72. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Stories of the Sky Islands: Exhibit Development Resource Guide for Biology and Geology at Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial

Stories of the Sky Islands: Exhibit Development Resource Guide for Biology and Geology at Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial Prepared for the National Park Service under terms of Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Agreement H1200-05-0003 Task Agreement J8680090020 Prepared by Adam M. Hudson,1 J. Jesse Minor,2,3 Erin E. Posthumus4 In cooperation with the Arizona State Museum The University of Arizona Tucson, AZ Beth Grindell, Principal Investigator May 17, 2013 1: Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona ([email protected]) 2: School of Geography and Development, University of Arizona ([email protected]) 3: Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona 4: School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona ([email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................3 Beth Grindell, Ph.D. Ch. 1: Current research and information for exhibit development on the geology of Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial, Southeast Arizona, USA..................................................................................................................................... 5 Adam M. Hudson, M.S. Section 1: Geologic Time and the Geologic Time Scale ..................................................5 Section 2: Plate Tectonic Evolution and Geologic History of Southeast Arizona .........11 Section 3: Park-specific Geologic History – Chiricahua -

Recent Wildfire Patterns of the Madrean Sky Islands of Southwestern United States and Northwestern Mexico Miguel L

Villarreal et al. Fire Ecology (2019) 15:2 Fire Ecology https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-018-0012-x ORIGINALRESEARCH Open Access Distant neighbors: recent wildfire patterns of the Madrean Sky Islands of southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico Miguel L. Villarreal1* , Sandra L. Haire2, Jose M. Iniguez3, Citlali Cortés Montaño4 and Travis B. Poitras1 Abstract Background: Information about contemporary fire regimes across the Sky Island mountain ranges of the Madrean Archipelago Ecoregion in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico can provide insight into how historical fire management and land use have influenced fire regimes, and can be used to guide fuels management, ecological restoration, and habitat conservation. To contribute to a better understanding of spatial and temporal patterns of fires in the region relative to environmental and anthropogenic influences, we augmented existing fire perimeter data for the US by mapping wildfires that occurred in the Mexican Sky Islands from 1985 to 2011. Results: A total of 254 fires were identified across the region: 99 fires in Mexico (μ =3901ha,σ = 5066 ha) and 155 in the US (μ =3808ha,σ = 8368 ha). The Animas, Chiricahua, Huachuca-Patagonia, and Santa Catalina mountains in the US, and El Pinito in Mexico had the highest proportion of total area burned (>50%) relative to Sky Island size. Sky Islands adjacent to the border had the greatest number of fires, and many of these fires were large with complex shapes. Wildfire occurred more often in remote biomes, characterized by evergreen woodlands and conifer forests with cooler, wetter conditions. The five largest fires (>25 000 ha) all occurred during twenty-first century droughts (2002 to 2003 and 2011); four of these were in the US and one in Mexico. -

Sceloporus Jarrovii)By Chiggers and Malaria in the Chiricahua Mountains, Arizona

THE SOUTHWESTERN NATURALIST 54(2):204–207 JUNE 2009 NOTE INFECTION OF YARROW’S SPINY LIZARDS (SCELOPORUS JARROVII)BY CHIGGERS AND MALARIA IN THE CHIRICAHUA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA GRE´ GORY BULTE´ ,* ALANA C. PLUMMER,ANNE THIBAUDEAU, AND GABRIEL BLOUIN-DEMERS Department of Biology, University of Ottawa, 30 Marie-Curie, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada *Correspondent: [email protected] ABSTRACT—We measured prevalence of malaria infection and prevalence and intensity of chigger infection in Yarrow’s spiny lizards (Sceloporus jarrovii) from three sites in the Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona. Our primary objective was to compare parasite load among sites, sexes, and reproductive classes. We also compared our findings to those of previous studies on malaria and chiggers in S. jarrovii from the same area. Of lizards examined, 85 and 93% were infected by malaria and chiggers, respectively. Prevalence of malaria was two times higher than previously reported for the same area, while prevalence of chiggers was similar to previous findings. Intensity of chigger infection was variable among sites, but not among reproductive classes. The site with the highest intensity of chigger infection also had the most vegetative cover, suggesting that this habitat was more favorable for non- parasitic adult chiggers. RESUMEN—Medimos la frecuencia de infeccio´n por malaria y la frecuencia e intensidad de infeccio´n por a´caros en la lagartija espinosa Sceloporus jarrovii de tres sitios en las montan˜as Chiricahua del sureste de Arizona. Nuestro objetivo principal fue comparar la carga de para´sitos entre sitios, sexos y clases reproductivas. Adicionalmente comparamos nuestros hallazgos con estudios previos sobre malaria y a´caros para esta especie en la misma a´rea. -

Forest Ecology and Management 329 (2014) 264–278

Forest Ecology and Management 329 (2014) 264–278 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Fire severity, size, and climate associations diverge from historical precedent along an ecological gradient in the Pinaleño Mountains, Arizona, USA ⇑ Christopher D. O’Connor a,c, , Donald A. Falk a,c, Ann M. Lynch b,c, Thomas W. Swetnam c a University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources and the Environment, 325 Biosciences East Building, Tucson, AZ 85721, United States b U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 1215 E. Lowell St., Tucson, AZ 85721, United States c University of Arizona, Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, 1215 E. Lowell St., Tucson, AZ 85721, United States article info abstract Article history: In recent decades fire size and severity have been increasing in high elevation forests of the American Received 13 May 2014 Southwest. Ecological outcomes of these increases are difficult to gauge without an historical context Received in revised form 26 June 2014 for the role of fire in these systems prior to interruption by Euro-American land uses. Across the gradient Accepted 27 June 2014 of forest types in the Pinaleño Mountains, a Sky Island system in southeast Arizona that experienced two relatively large high-severity fires in the last two decades, we compared fire characteristics and climate associations before and after the onset of fire exclusion to determine the degree of similarity between Keywords: past and recent fires. We use a gridded fire scar and demography sampling network to reconstruct spa- Spatial reconstruction tially explicit estimates of fire extent and burn severity, as well as climate associations of fires from indi- Fire history Elevation gradient vidual site to landscape scales from 1640 to 2008 C.E. -

Sprint Performance of Phrynosomatid Lizards, Measured on a High-Speed Treadmill, Correlates with Hindlimb Length

J. Zool., Lond. (1999) 248, 255±265 # 1999 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom Sprint performance of phrynosomatid lizards, measured on a high-speed treadmill, correlates with hindlimb length Kevin E. Bonine and Theodore Garland, Jr Department of Zoology, University of Wisconsin, 430 Lincoln Drive, Madison, WI 53706-1381, U.S.A. (Accepted 19 September 1998) Abstract We measured sprint performance of phrynosomatid lizards and selected outgroups (n = 27 species). Maximal sprint running speeds were obtained with a new measurement technique, a high-speed treadmill (H.S.T.). Animals were measured at their approximate ®eld-active body temperatures once on both of 2 consecutive days. Within species, individual variation in speed measurements was consistent between trial days and repeatabilities were similar to values reported previously for photocell-timed racetrack measure- ments. Multiple regression with phylogenetically independent contrasts indicates that interspeci®c variation in maximal speed is positively correlated with hindlimb span, but not signi®cantly related to either body mass or body temperature. Among the three phrynosomatid subclades, sand lizards (Uma, Callisaurus, Cophosaurus, Holbrookia) have the highest sprint speeds and longest hindlimbs, horned lizards (Phryno- soma) exhibit the lowest speeds and shortest limbs, and the Sceloporus group (including Uta and Urosaurus) is intermediate in both speed and hindlimb span. Key words: comparative method, lizard, locomotion, morphometrics, phrynosomatidae, sprint speed INTRODUCTION Fig. 1; Montanucci, 1987; de Queiroz, 1992; Wiens & Reeder, 1997) that exhibit large variation in locomotor Evolutionary physiologists and functional morpholo- morphology and performance, behaviour, and ecology gists emphasize the importance of direct measurements (Stebbins, 1985; Conant & Collins, 1991; Garland, 1994; of whole-animal performance (Arnold, 1983; Garland & Miles, 1994a). -

The Madrean Sky Island Archipelago: a Planetary Overview, Peter Warshall

The Madrean Sky Island Archipelago: A PlanetaryOverview PeterWarshaltl Abstract.-Previouswork on biogeographicisolation hAFoncerned itself with oceanicisland chains, islands associated with continents, fringingarchipelagos, and bodiesof watersuch as the Africanlake system which serue as "aquaticislands". This paper reviewsthe "continentalislands" and comparesthem to the Madreansky island archipelago.The geological,hydrological, and climaticcontext for the Afroalpine,Guyana, Paramo, low and high desert of theGreat Basin, etc. archipelagosare comparedfor source areas, number of islands, isolating mechanisms,interactive ecosystems, and evolutionary history. The history of scientificexploration and fieldworkfor the Madrean Archipelagoand its uniquestatus among the planet'sarchipelagos are summarized. In 1957,Joe Marshall published "Birds of the American Prairies Province of Thkhtajan, 1986) Pine-Oak Woodland in Southern Arizona artd Ad- and western biogeographic provinces, a wealth of jacent Mexico." Never surpassed, this elegant genetically unique cultivars in the Sierra Madre monograph described the stacking of biotic com- Occidental, and a myriad of mysteries concerning munities on each island mountain from the the distribution of disjuncts, species "holes," and Mogollon Rim to the Sierra Madre. He defined the species "outliers" on individual mountains (e.g., Madrean archipelago as those island mountains Ramamoorthy, 7993). The northernmost sky is- with a pine'oak woodland.lnl967, Weldon Heald lands are the only place in North America where (1993), from his home in the Chiricahuas, coined vou can climb from the desert to northern Canada the addictive phrase-"sky islands" for these in- in a matter of hours (Warshall, 1986). The sky is- sular mountains of the North American lands pose numerous puzzles about vertical borderlands. Weldon Heald's catch phrase immor- migration strategies used by plants and animals talized |oe Marshall's meticulous observations. -

Sky Islands Children's Forest Strategic Plan

Sky Islands Children’s Forest Strategic Plan 2012 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Coronado National Forest Sky Islands Children’s Forest Strategic Plan Coronado National Forest 1 Sky Islands Children’s Forest Strategic Plan Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................3 What is a Children’s Forest? .......................................................................................................................................5 Purpose of this Strategy .............................................................................................................................................5 Background .................................................................................................................................................................6 Sky Islands Children’s Forest ......................................................................................................................................8 Vision, Mission and Guiding Principles ...................................................................................................................9 Goals, Strategies, and Actions ................................................................................................................................9 Evaluation and Measures ................................................................................................................................... -

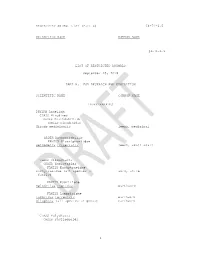

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes