Outer Space As Liminal Space: Folklore and Liminality On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

Bloodsuckers Doom Coalition Finished Picture Plus!

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES ISSUE 92 • OCTOBER 2016 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF CARDIFF'S FINEST! PLUS! JAGO & LITEFOOT! DOCTOR WHO! DORIAN GRAY! BLOODSUCKERS DOOM COALITION FINISHED PICTURE A BARMAID GOES BAD! THIRD SERIES OVERVIEW! FINAL SERIES PREVIEW! HEADING WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio dramas and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories! at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Dark Shadows, Blake's 7, The Avengers and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a Survivors as well as classic characters such as bonus release, downloadable audio readings of Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera new short stories and discounts. and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The You can access a video guide to the site at Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. www.bigfinish.com/news/v/website-guide-1 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @ BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH WELCOME TO VORTEX EDITORIAL SNEAK PREVIEW COLD FUSION OOM COALITION is a very clever thing. Each story needs to be able to stand on its D own, as a piece of entertaining drama. But the four stories in each box set need to unify to tell a bigger story, which feels complete in its own right. But then, the four box sets need to work together, to relate a full adventure in 16 parts. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

GALACTICA DISCOVERS EARTH (Early Draft) by Glen A

GALACTICA 1980 GALACTICA DISCOVERS EARTH (early draft) by Glen A. Larson Revision Date: November 26, 2979 FADE IN ON A BEAUTIFUL STARFIELD - NIGHT WALTER Fantastic, isn't it... Do you ever wonder if there's life out there? We are on an average looking guy, in average casual clothes, circa 1980. He is in an average compact car with a sunroof, through which Walter gazes skyward, his arm draped off screen. We follow his arm with camera to take in a prettier than average young woman who seems interested in anything but Walter and the stars. JAMIE I'm not too sure there's even life around here. Walter's eyes drift down and over, his mood shattered. WALTER What? JAMIE I've had it... WALTER What'd I do now? JAMIE Nothing... It's what I did... WALTER You've been like this for a week... If it's the wedding, we can move it up... I just thought your folks would prefer... JAMIE Walter... It isn't working... WALTER You don't mean us... JAMIE Walter... I don't mean you and me... I mean me and this planet... It just isn't working out... I got passed over today... 2. WALTER Passed over for what... Head of the steno pool... Once we're married I don't want you working anyway... JAMIE I didn't apply for head of the steno pool... I was interviewed by Scott to get an on-camera assignment... WALTER On-camera... You? JAMIE And what's that supposed to mean? I don't have the brains to be a good field reporter.. -

Super Mage Beastiary

The Super Mage Bestiary by Dean Shomshak HERO GAMES The Super Mage Bestiary by Dean Shomshak Editing & Layout: Ellen Porter Kiley Illustrations: Derek Stevens Cover Coloration: Alia Ogron Page Number Icon: Robert W. Fetterolf Kallamar Title Font: Eric VanDycke Managing Editor: Bruce Harlick Copyright @1999 by Hero Games. All rights reserved. Hero System, Fantasy Hero, Champions, Hero Games and Star Hero are all registered trademarks of Hero Games. Acrobat and the Acrobat logo are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated which may be registered in certain jurisdictions. All other trade- marks and registered trademarks are properties of their owners. Published by Hero Plus, a division of Hero Games. Hero Plus Hero Plus is an electronic publishing company, using the latest technology to bring products to customers more efficiently, more rapidly, and at competitive prices. Hero Plus can be reached at [email protected]. Let us know what you think! Send us your mailing address (email and snail mail) and we’ll make sure you’re informed of our latest products. Visit our Web Site at http://www.herogames.com Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 5 Contents..................................................................................................................................... 6 Use In Other Genres ................................................................................................................. 6 Where They Come -

See What's on ¶O – Lelo This Week, This Hour, This Second

FOR THE WEEK OF MAY 28 - JUNE 3, 2017 THE GREAT INDEX TO FUN DINING • ARTS • MUSIC • NIGHTLIFE Look for it every Friday in the HIGHLIGHTS THIS WEEK on Fox. Jamie Foxx hosts this new game show, which TODAY TUESDAY features Shazam, the world’s most popular song identi- The Leftovers World of Dance fication app. HBO 6:00 p.m. KHNL 9:00 p.m. FRIDAY Kevin (Justin Theroux) assumes an alternate identity Extraordinary dancers from all ages and walks of life Shark Tank when he embarks on a mission of mercy in a new epi- kick off the qualifier round for the chance to win a life- sode of “The Leftovers,” airing today on HBO. altering $1-million prize in the premiere of “World of KITV 7:00 p.m. The post-apocalyptic drama follows a family of survi- Dance,” airing Tuesday on NBC. Jenna Dewan Tatum vors a few years after the mysterious simultaneous dis- serves as mentor and host, while Jennifer Lopez, Business moguls decide whether or not to invest appearance of 140 million people. Derek Hough and Ne-Yo serve as judges. their own money in new products and companies in back-to-back episodes of the critically acclaimed reali- ty TV series “Shark Tank,” airing Friday on ABC. MONDAY WEDNESDAY Hopeful entrepreneurs pitch their ideas in the hopes of Lucifer The F Word snagging a deal with a Shark. KHON 8:00 p.m. KHON 8:00 p.m. SATURDAY Charlotte (Tricia Helfer) acciden- Celebrity chef and TV personality Gordon Ram- To Tell the Truth tally charbroils a man to death say hosts as foodie families and friends compete in self-defence, and Lucifer in high-stakes cook-offs in “The F Word,” pre- KITV 7:00 p.m. -

The Women of Battlestar Galactica and Their Roles : Then and Now

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 The women of Battlestar Galactica and their roles : then and now. Jesseca Schlei Cox 1988- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cox, Jesseca Schlei 1988-, "The women of Battlestar Galactica and their roles : then and now." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 284. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/284 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WOMEN OF BATTLESTAR GALACTICA AND THEIR ROLES: THEN AND NOW By Jesseca Schleil Cox B.A., Bellarmine University, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degre:e of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2013 Copyright 2013 by Jesseca Schlei Cox All Rights Reserved The Women of Battlestar Galactica and Their Roles: Then and Now By Jesseca Schlei Cox B.A., Bellarmine University, 2010 Thesis Approved on April 11, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Gul Aldikacti Marshall, Thesis Director Cynthia Negrey Dawn Heinecken ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my mother and grandfather Tracy Wright Fritch and Bill Wright who instilled in me a love of science fiction and a love of questioning the world around me. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Apocalypse As Religious and Secular Discourse in Battlestar Galactica

Volume 6 2014-15 APOCALYPSE & GHOSTS Apocalypse as Religious and Secular Discourse in Battlestar Galactica and its Prequel Caprica Diane Langlumé University of Paris VIII Saint-Denis Abstract he concept of the end of the world is inherent in religious discourse. Illustratively, in T Medieval Christianity, a divine power was held responsible for cataclysmic events. In the post-Hiroshima era, the concept of apocalypse has taken on secular meaning. Not surprisingly, given recent history, the apocalypse has become a prominent component of popular television epics; broadcast narratives, such as Battlestar Galactica and Caprica, entwine both Biblical and secular versions of the apocalypse, thereby creating a novel apocalyptic discourse which, instead of establishing the apocalypse as an end, uses it as a foundation, as a thought-provoking means of conveying a political message of tolerance and acceptance of otherness, of encouraging self-reflectiveness; and as a way of denouncing the empty rhetoric of religious extremism. Keywords: Television series, Battlestar Galactica, Caprica, religion, Book of Mormon, Bible, Book of Revelation, John of Patmos, Genesis, Adam, Garden of Eden, Heaven, God, fall of man, the beast, false prophet, angel, Second Coming, resuscitation, apocalypse, end of the world, nuclear apocalypse, Hiroshima, post-apocalyptic, genocide, intertextuality, parody, pastiche, religious satire, 9/11, America, religious terrorism, suicide bombing, cyborg, robot, humanity, monotheism, polytheism. he television series Battlestar Galactica1 establishes its chronology between a nuclear T apocalypse that has just taken place and the threat of a potential future apocalypse,2 both at the hands of human-looking cyborgs called Cylons. Caprica, its prequel series, set fifty- eight years before the nuclear detonation, unfolds the events leading up to the apocalypse in Battlestar Galactica. -

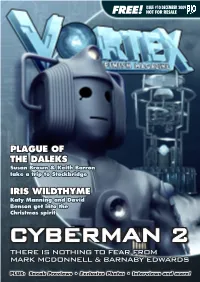

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Doctor Who 4 Ep.14

Doctor Who 4 Episode 14 (Christmas 08) By Russell T Davies Shooting Script Pink Revisions 3rd April 2008 Prep starts: 10.03.08 Shooting: 07.04.08 - 03.05.08Tale Writer's The Doctor Who 4 - Episode 14 - Shooting Script - 31/03/08 page 1. 1 OMITTED 1 2 EXT. VICTORIAN STREET #1 - DAY 1 2 FX: a quiet corner; wheeze & grind, and the TARDIS appears. THE DOCTOR steps out. It's snowing. He likes snow! He strolls out of the quiet corner, into... A STREET MARKET. Working class London, busy and bustling. Vendors, cocky lads, working girls, crones, braziers, beggars in doorways, hot chestnuts, smoke, steam, the works. The Doctor walking through. Smiling. He's loving it, the colour and bustle and noise; this is what he travels for. Throughout all this, a CAROL can be heard; a new Murray Gold Christmas Carol. Jolly & sinister, like the best hymns. The Doctor passes the CAROLLERS, stops for a listen. Then he wanders on, calls out to an URCHIN: THE DOCTOR You there, boy, what day is this? URCHIN Tale Christmas Eve, sir! THE DOCTOR In what year? URCHIN You thick or something? THE DOCTOR Oy! AnswerWriter's the question! URCHIN Year of our Lord 1851, sir. THE DOCTOR TheRight. Nice year. Bit dull - Suddenly, a woman's voice, a distance away, yelling - ROSITA OOV Doctor! THE DOCTOR ...who, me? ROSITA OOV Doctor!!! Big grin! And he's running - ! (CONTINUED) Doctor Who 4 - Episode 14 - Pink Amendments - 03/04/08 page 2. 2 CONTINUED: 2 TRACK with him, racing through the snow, exhilarated - he's actually glad to hear someone calling his name - CUT TO: 3 EXT.