SAHS Transactions XXVII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synopsis of the Archaeology of the Sandwell Priory and Holy Well

APPENDIX 4 SELECT COMMITTEE ON HERITAGE AND CULTURE SYNOPSIS OF ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE SANDWELL PRIORY AND HOLY WELL Comments of Planning Archaeologist This paper represents the undertaking and finding of work carried out during the past thirty years at the above site. The site of Sandwell Priory, Sandwell Hall and the Holy Well lie 2km east of West Bromwich town centre, in a public open space known as Sandwell Valley Country Park. The first known archaeological excavations occurred on the site in 1958, with the aim of re-erecting large sections of the ruins. There are no records of this excavation with the exception of a newspaper account of the work. The major excavation work on the priory site was initiated by the Technical and Development Services Department of Sandwell MBC in August 1982 as an adjunct to the restoration of the nearby Sandwell Park Farm, with the aim of enhancing knowledge of the historic development of the Sandwell Valley. The archaeological excavations were ended in August 1988 and masonry exposed as a result of the work was subsequently consolidated for permanent display. The assemblage of artefacts that were collected as a result of the excavation has been stored within the cellarage of Wednesbury Museum with the exception of those used for display at Sandwell Park Farm. The excavations were undertaken as part of the Sandwell Valley Archaeological Project initially directed by Dr M A Hodder 1982 – 1987 and later by Mr G C Jones 1987 – 1988. Dr Hodder went on to become the first Borough Archaeologist for Sandwell. The excavation was financed by the Manpower Services Commission, and sponsored by Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council. -

Walk West Bromwich

SMBC/WM 2006.02 OAK HOUSE west bromwich “A wonderful specimen of English life and history” WEST BROMWICH CENTRAL LIBRARY walk From the original yellow of “What a beautiful building, the mosaics and stained west bromwich. furze bushes and heathland, glass are truly stunning” heritage trail through the black and fiery SANDWELL PARK FARM reds of industrialisation, “I love my visit, every time I visit it’s just the best” to the vibrant pink and SANDWELL VALLEY silver of recent building, “Thank you Sandwell for maintaining and enhancing this jewel shining in the surrounding desert” West Bromwich today DARTMOUTH PARK presents a vibrant and living “This place is a haven of peace and pleasure kaleidoscope of people to walk around” and buildings sharing a fascinating past and inspiring future. Named after the “Broom” bush and Wic meaning heath, WEST BROMWICH “Broom Wic” was a Saxon settlement to which West was Directions: later added in about 650 AD to distinguish it from other Metro info: Bromwiches. Saxon and Mediaeval farmland was gradually tel: 0121 254 7272 replaced in the 1500s and 1600s as industries like web: www.travelmetro.co.uk nailmaking and gunlock filing flourished. Small iron works sprang up and mines were dug to exploit iron and coal. Bus and rail info: The opening of a canal in 1769 and the first railway station Traveline: 0870 608 2608 Centro Hotline: 0121 200 2700 in 1837 together with new and improved roads made the web: www.centro.org.uk transport of raw materials and finished goods easier and National Rail: 08457 48 49 50 increased the importance of West Bromwich as a prosperous and wealthy industrial town. -

Report of the Select Committee on Heritage and Culture Sandwell’S Heritage

Oldbury Rowley Regis Smethwick Tipton Wednesbury West Bromwich Sandwell’s Heritage Report of the Select Committee on Heritage and Culture Sandwell’s Heritage JULY 2005 Sandwell Heritage Report of The Select Committee on Heritage and Culture Contents Page No 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Sandwell’s Heritage – An Overview 1 1.2 Purpose of Select Committee – Phase 1 2 1.3 Context 2 1.4 Proceedings of The Select Committee 3 1.5 Select Committee’s Achievements to Date 3 1.6 Overarching Recommendations 4 2. Physical Assets 6 2.1 Summary of Arguments Put Before The Select 6 Committee 2.1.1 Historic Buildings, Structures & Parks - Overview 6 2.1.2 Priorities for Historic Buildings, Structures and 8 Parks 2.1.3 Findings from Exemplar Buildings 9 2.1.3.1 Oak House, Oak House Barns and Stocks 9 2.1.3.2 West Bromwich Manor House and Manager’s 9 House 2.1.3.3 Cobbs Engine House and Chimney 10 2.1.3.4 Sandwell Priory and Well 10 2.1.3.5 Ingestre Hall 11 2.1.3.6 Haden Hall and Stable Block, Haden Hill Estate 11 2.1.4 Findings from Other Historic Buildings and Sites 12 2.1.4.1 Visitor Centres 12 2.1.4.2 Heritage Listed Parks 13 Sandwell’s Heritage Page No 2.1.4.3 Conservation Areas 14 2.1.4.4 Chain Shop, Temple Meadow Primary School, 14 Cradley Heath 2.1.4.5 Canal Infrastructure / Bid for World Heritage Status 15 2.1.4.6 Soho Foundry 16 2.1.4.7 Soho House 17 2.1.4.8 Black Country Living History Museum, Dudley 17 2.1.5 Other Issues for Historic Buildings and Sites 17 2.1.5.1 Development Priorities within the Museums Service 17 2.1.5.2 Data Collection on the Historic Environment / Local 18 Listing 2.1.5.3 Community Venues / Borough-wide Venues 18 2.1.5.4 Access for People with Disabilities 19 2.2 Conclusions of The Select Committee 20 2.3 Recommendations of The Select Committee 21 3. -

Newsletter 135 September 2020

1 STAFFORDSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER September 2020 Web: www.sahs.uk.net Issue No 135 email: [email protected] Hon. President: Dr John Hunt B.A., Ph.D., F.S.A., F.R.Hist.S., P.G.C.E. tel: 01543 423549 Hon. General Secretary: Steve Lewitt B.A. (Oxon.), M.A., P.G.C.E., P.G.C.R.M., F.C.I.P.D., F.R.S.A. Hon. Treasurer: Keith Billington A.C.I.B. tel: 01543 278989 The Church of St. Matthew, Walsall Contents include ‘Geoffrey de Mala Terra and Goffredo Malaterra’ by A J and E A Yates page 3 ‘A Lightning Strike at St Matthew’s Church, Walsall’ by Diana M Wilkes page 3 ‘Archaeology for Pevsner’ by Mike Hodder page 10 Autumn Lectures in Lichfield Guildhall Postponed – page 2 2 A Message from Dr John Hunt, Honorary President As for most societies and organisations, the Covid-19 pandemic and the restrictions necessary to ‘live with it’ has meant that it has now been nearly six months since SAHS was last able to organise an event for our membership. We have all been disappointed not to hear the excellent cast of speakers lined up for us, or to be able to participate in our usual programme of field visits. We have however been able to publish our Transactions as normal, and to continue with the publication of our Newsletters, in addition to which numerous online ‘extras’ have hopefully mitigated some of the disappointment felt at the disruption to our activities. Unfortunately, I have to inform you that this disruption is set to continue. -

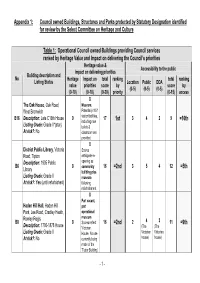

Schedule of Historic Buildings, Structures and Parks Protected By

Appendix 1: Council owned Buildings, Structures and Parks protected by Statutory Designation identified for review by the Select Committee on Heritage and Culture Table 1: Operational Council owned Buildings providing Council services ranked by Heritage Value and Impact on delivering the Council’s priorities Heritage value & Accessibility to the public impact on delivering priorities Building description and No Heritage Impact on total ranking total ranking Listing Status Location Public DDA value priorities score by score by (0-5) (0-5) (0-5) (0-10) (0-10) (0-20) priority (0-15) access 8 The Oak House, Oak Road, Museum. West Bromwich Potentially 10 if B16 Description: Late C16th House 9 visitor facilities, 17 3 4 2 9 including new 1st =16th Listing Grade: Grade II*(star) toilets & At risk?: No classroom are provided 8 District Public Library, Victoria Scores Road, Tipton anticipate re- Description: 1905 Public opening as B6 8 community 16 =2nd 3 5 4 12 =5th Library building plus Listing Grade: Grade II museum At risk?: Yes (until refurbished) following refurbishment 8 Part vacant, Haden Hill Hall, Haden Hill part Park, Lee Road, Cradley Heath, operational Rowley Regis museum B8 8 Scores reflect 16 =2nd 2 4 3 11 =9th Description: 1700-1878 House Victorian (The (The Listing Grade: Grade II House. No use Victorian Victorian At risk?: No currently being house) house) made of the ‘Tudor Building’ - 1 - Table 1: Operational Council owned Buildings providing Council services ranked by Heritage Value and Impact on delivering the Council’s priorities -

SAHS Transactions Volume XXV111

Staffordshire SampleCounty Studies StaffordshireSOUTH STAFFORDSHIR E ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY TRANSACTIONSampleCounty S FOR 1986-1987 VOLUME XXVIII Studies Walsall 1988 StaffordshireCONTENT S 'LICHFIELD' AND 'ST. AMPHIBALUS': THE STORY OF A LEGEND DOUGLAS JOHNSON 1 A LANDSCAPE SURVEY OF SANDWELL VALLEY, 1982-87 N. R. HEWITT AND M. A. HODDER 14 ALL SAINTS' CHURCH, WEST BROMWICH: MEDIEVAL FLOOR TILES, AN ARCHITECTURAL FRAGMENT, AND AN EXCAVATION M. A. HODDER 39 MEDIEVAL FLOOR TILES FROM WEST BROMWICH MANOR HOUSE M. A. HODDER 42 THE DOVECOTE FROM HASELOUR HALL, HARLASTON, STAFFORDSHIRE SIMON A. C. PENN SampleCounty 44 EXCAVATIONS AT MOAT FARM, PELSALL, 1982 AND 1984: A POST-MEDIEVAL FARMSTEAD J. MILLNANDM. A. HODDER 51 AN EARLY EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY DESCRIPTION OF LICHFIELD CATHEDRAL NIGEL J. TRINGHAM 55 OFFICERS, 1986-87 Studies64 PROGRAMME, 1986-87 65 LIST OF FIGURES Pages StaffordshireLANDSCAPE SURVEY OF SAND WEL L VALLEY Fig. 1 Sandwell Valley: location and relief 15 Fig. 2 Recording forms 16 Fig. 3 Sandwell Valley: Pre-Priory 18 Fig. 4 Sandwell Valley: plans and sections of burnt mound 20 Fig. 5 Sandwell Valley: features around Sandwell Priory and Sandwell Hall 21 Fig. 6 Sandwell Valley: sections of excavated features 22 Fig. 7 Sandwell Valley: Priory and immediate post-Priory 24 Fig. 8 Sandwell Valley: Dartmouth period, Sandwell Hall and gardens . 28 Fig. 9 Sandwell Valley: Dartmouth period 29 Fig. 10 Sandwell Valley: greenhouse and rickyard 30 Fig. 11 Sandwell Valley: plan of heated greenhouse 32 Fig. 12 Sandwell Valley: Post-Dartmouth 36 ALL SAINTS' CHURCH, WEST BROMWICH Fig. 1 Medieval flooSampler tile designs and architectural feature 40 MEDIEVAL FLOOR TILES FROM WESTCounty BROMWICH MANOR HOUSE Fig. -

Download This File

the Sandwell Sandwell @sandwellcouncil erald www.sandwell.gov.uk H SUMMER 2017 Summertime in Sandwell Lightwoods House, Bearwood House, Lightwoods Sign up to Sandwell Council email updates Follow the bears this Discover Sandwell: 100 of the things the News from your www.sandwell.gov.uk/emailupdates summer: Page 2 Page 4 council does: Pages 5-7 town: Pages 18-23 2 The Sandwell Herald Are you online? Follow those bears! Save time with MySandwell We’re busy adding more services to our MySandwell portal – saving The Big Sleuth comes to Sandwell you time and the need to call us to report a problem or request a We’re very proud to be part of The Big Sleuth – service. a brilliant public art trail bringing bear-illiant bears to Sandwell. You can now report an environmental health issue and even record a The 10-week project supporting Birmingham The trail, which is being run in conjunction with noise nuisance diary online. Children’s Hospital Charity will see up to 100 Wild in Art, is on until Sunday 17 September. And soon you’ll be able to book a pest control appointment through decorated bear sculptures on display in the region’s During that time we want as many people as your account. streets, parks and open spaces. possible to visit all of the bears, check out The Big All you need to do is register for a MySandwell account – it takes a few Sleuth app and have fun! moments. Then you can access all of these services and more online: A sleuth is the collective noun for a group of bears and you’ll be able to sleuth your way around the Three of the bears will be auctioned off in aid of Council tax and benefits – check your council tax bill, benefits and trail which includes Sandwell, Birmingham, Solihull, Birmingham Children’s Hospital Charity in the business rates balances and transactions Sutton Coldfield and Resorts World. -

SAHS Transactions Volume XXXI

Staffordshire SampleCounty Studies Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council, Department of Technical and Development Services, P.O. Box 42, West Bromwich, B71 3RZ SANDWELL VALLEY ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT StaffordshirePROJECT STAFF , 1982-1988 Project Directors: M. A. Hodder (1982-1987), G. C. Jones (1987-1988) Supervisors: R. Barnes A. Cox J. Hall S. Jeffery D. Sandhu J. Carmichael J. Glazebrook N. Hewitt A. Lenihan S. Webster L. Collett J. Glew G. Higgerson S. O'Donnell T. Westwood K. Corbett I. Greig G. Higginson Staff: K. Adams I. Clews T. Green M. Maydew A. Skipp M. Adolf J. Conniff M. Griffiths L. Mills A. Skitt P. Ahmed B. Cooke J. Groves P. Moore H. Smith M. Alcock C. Cooper B. Haley B. O'Carroll S. Smith F. Ali A. Cottrell P. Handley L. O'Connor T. Smith J. Anslow M. DabbSamples P. HandCountys E. O'Donnel l P. Spruce R. Archer S. Darby P. Hennefer S. O'Donnell C. Staddon D. Aston G. Davies W. Hocknull K. Parker M. Stanyer L. Aston N. Davies T. Hodgetts A. Parry G. Stevens P. Atkinson S. Davies I. Hough B. Patel P. Stevens T. Austin J. Day J. Hoult D. Patel H. Summers L. Baker S. Dixon P. Huggins R. Pearce A. Tarifa P. Baker P. Downer D. Issac A. Perry T. Taylor S. Banfield S. Driver D. James C. Perry D. Thompson P. Banner D. Ebanks D. Johnson D. Perry L. Thompson C. Barnett J. Eley R. Jones D. Pitt StudiesL. Thompson K. Beddington C. Emery R. Jones M. Power J. Turner M. Bentley A. Emms T. -

Sandnats Bulletin

SANDNATS BULLETIN ROOK –A SANDWELL VALLEY REGULAR By Terry Parker Cover Picture ‘ Red Fox’ by Andy Purcell– this year we are experimenting with a new layout & our thanks go to Andy for a long unbroken series of terrific cover photos. SANDNATS BULLETIN MARCH 2008 PAGE 1 Sandwell Valley Naturalists’ Club (SANDNATS) was formed in 1975. Its members work to conserve the Valley’s wildlife, help others to enjoy it, and liaise with Sandwell Council about the management of the Valley. OFFICERS PRESIDENT - John Shrimpton CONTENTS PAGE 3 Editorial. VICE-PRESIDENTS Freda Briden, Peter Shirley PAGE 4 Chairman’s Report. PAGE 5 Club Accounts. CHAIR - Tony Wood PAGE 7 Meeting Reports TREASURER - Jane Hardwick PAGE 17 Entomology Report SECRETARY Margaret Shuker . (0121 357 1067) PAGE 19 Ornithology Report MEMBERSHIP - Marian Brevitt PAGE 25 Botany Report 165 Queslett Road, Great Barr, Birmingham, B43 6DS PAGE 29 S.V. Staff Report BULLETIN EDITOR –Mike Bloxham. PAGE 31 Mammals & amphibians (0121 553 3070) PAGE 34 ‘From Bill Stott to PRESS OFFICER - Tony Wood Biodiversity’ PAGE 63 Forthcoming publications COMMITTEE MEMBERS and other reports Sheila Hadley, Mike Poulton, and Bill Moodie. HON AUDITORS Peter Shirley & Arthur Stevenson SANDNATS BULLETIN MARCH 2007 PAGE 2 EDITORIAL First of all, an apology about lost editions. Yes– you’ve all heard it before and the loss of the special edition for November 2007 was indeed a little more than carelessness. The editor’s fires went out, but an attempt to re-kindle them is now afoot with a fresh year and the whiff of change in the air. This number attempts to combine the annual report with the lost November number, taking a final look back into wildlife history of the Sandwell Valley and thus bringing to an end a series of writings commemorating the founding of the Club .