Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerius Maximus on Vice: a Commentary of Facta Et Dicta

Valerius Maximus on Vice: A Commentary on Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 9.1-11 Jeffrey Murray University of Cape Town Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the School of Languages and Literatures University of Cape Town June 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract The Facta et Dicta Memorabilia of Valerius Maximus, written during the formative stages of the Roman imperial system, survives as a near unique instance of an entire work composed in the genre of Latin exemplary literature. By providing the first detailed historical and historiographical commentary on Book 9 of this prose text – a section of the work dealing principally with vice and immorality – this thesis examines how an author employs material predominantly from the earlier, Republican, period in order to validate the value system which the Romans believed was the basis of their world domination and to justify the reign of the Julio-Claudian family. By detailed analysis of the sources of Valerius’ material, of the way he transforms it within his chosen genre, and of how he frames his exempla, this thesis illuminates the contribution of an often overlooked author to the historiography of the Roman Empire. -

Vestal Virgins and Their Families

Vestal Virgins and Their Families Andrew B. Gallia* I. INTRODUCTION There is perhaps no more shining example of the extent to which the field of Roman studies has been enriched by a renewed engagement with anthropology and other cognate disciplines than the efflorescence of interest in the Vestal virgins that has followed Mary Beard’s path-breaking article regarding these priestesses’ “sexual status.”1 No longer content to treat the privileges and ritual obligations of this priesthood as the vestiges of some original position (whether as wives or daughters) in the household of the early Roman kings, scholars now interrogate these features as part of the broader frameworks of social and cultural meaning through which Roman concepts of family, * Published in Classical Antiquity 34.1 (2015). Early versions of this article were inflicted upon audiences in Berkeley and Minneapolis. I wish to thank the participants of those colloquia for helpful and judicious feedback, especially Ruth Karras, Darcy Krasne, Carlos Noreña, J. B. Shank, and Barbara Welke. I am also indebted to George Sheets, who read a penultimate draft, and to Alain Gowing and the anonymous readers for CA, who prompted additional improvements. None of the above should be held accountable for the views expressed or any errors that remain. 1 Beard 1980, cited approvingly by, e.g., Hopkins 1983: 18, Hallett 1984: x, Brown 1988: 8, Schultz 2012: 122. Critiques: Gardner 1986: 24-25, Beard 1995. 1 gender, and religion were produced.2 This shift, from a quasi-diachronic perspective, which seeks explanations for recorded phenomena in the conditions of an imagined past, to a more synchronic approach, in which contemporary contexts are emphasized, represents a welcome methodological advance. -

ROMAN POLITICS DURING the JUGURTHINE WAR by PATRICIA EPPERSON WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State

ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR By PATRICIA EPPERSON ,WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State University Tahlequah, Oklahoma 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1975 SEP Ji ·J75 ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR Thesis Approved: . Dean of the Graduate College 91648 ~31 ii PREFACE The Jugurthine War occurred within the transitional period of Roman politics between the Gracchi and the rise of military dictators~ The era of the Numidian conflict is significant, for during that inter val the equites gained political strength, and the Roman army was transformed into a personal, professional army which no longer served the state, but dedicated itself to its commander. The primary o~jec tive of this study is to illustrate the role that political events in Rome during the Jugurthine War played in transforming the Republic into the Principate. I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Neil Hackett, for his patient guidance and scholarly assistance, and to also acknowledge the aid of the other members of my counnittee, Dr. George Jewsbury and Dr. Michael Smith, in preparing my final draft. Important financial aid to my degree came from the Dr. Courtney W. Shropshire Memorial Scholarship. The Muskogee Civitan Club offered my name to the Civitan International Scholarship Selection Committee, and I am grateful for their ass.istance. A note of thanks is given to the staff of the Oklahoma State Uni versity Library, especially Ms. Vicki Withers, for their overall assis tance, particularly in securing material from other libraries. -

THE PONTIFICAL LAW of the ROMAN REPUBLIC by MICHAEL

THE PONTIFICAL LAW OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC by MICHAEL JOSEPH JOHNSON A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Classics written under the direct of T. Corey Brennan and approved by ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2007 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Pontifical Law of the Roman Republic by MICHAEL JOSEPH JOHNSON Dissertation Director: T. Corey Brennan This dissertation investigates the guiding principle of arguably the most important religious authority in ancient Rome, the pontifical college. Chapter One introduces the subject and discusses the hypothesis the dissertation will advance. Chapter Two examines the place of the college within Roman law and religion, giving particular attention to disproving several widely held notions about the relationship of the pontifical law to the civil and sacral law. Chapter Three offers the first detailed examination of the duties of the pontifical college as a collective body. I spend the bulk of the chapter analyzing two of the three collegiate duties I identify: the issuing of documents known as decrees and responses and the supervision of the Vestal Virgins. I analyze all decrees and responses from the point of view their content, treating first those that concern dedications, then those on the calendar, and finally those on vows. In doing so my goal is to understand the reasoning behind the decree and the major theological doctrines underpinning it. In documenting the pontifical supervision of Vestal Virgins I focus on the college's actions towards a Vestal accused of losing her chastity. -

Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus Augustus 63 B.C. - 14 A.D

Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus Augustus 63 B.C. - 14 A.D. Rise to Power 44 B.C. Although great-nephew to Julius Caesar, Octavius was named Caesar’s adopted son in his will; at the age of eighteen, he became Caesar’s heir, inherit- ing, besides his material estate, the all- important loyalty of Caesar’s troops. By law required to assume the name Octavianus to reflect his biological origins, he raised a large army in Italy, and swayed two legions of his rival Marcus Antonius to join his army. 43 B.C. Following the deaths of the ruling consuls, Hirtius and Pansa, in fighting between Antony and the senate’s forces, Octavian was left in sole command of the consular armies. When the senate attempted to grant their command to Decimus Brutus, one of Caesar's assassins, Octavian refused to hand over the armies, and marched into Rome at the head of eight legions. He had demanded the consulship; when the senate refused, he ran for the office, and was elected. Marc Antony formed an alliance with Marcus Lepidus. Recognizing the undeniable strength of Octavian’s support, the two men entered into an arrangement with him, sanctioned by Roman law, for a maximum period of five years. This limited alliance, designed to establish a balance in the powers among the three rivals while also increasing their powers, was called the Second Triumvirate. Octavian, Antony and Lepidus initiated a period of proscriptions, or forcible takeovers of the estates and assets of wealthy Romans. While the primary reason for the campaign was probably to gain funds to pay their troops, the proscriptions also served to eliminate a number of their chief rivals, critics, and any- one who might pose a threat to their power. -

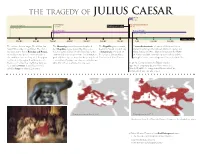

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

THE TR AGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR Transition 49–27 BC Coriolanus Caesar assassinated Roman Kingdom 494 BC Shakespeare’s play 44 BC 753–509 BC Roman Republic Roman Empire 509–49 BC 27 BC – 293 AD Roman Epochs 700 BC 600 BC 500 BC 400 BC 300 BC 200 BC 100 BC 1 AD 100 AD 200 AD The enforced vestal virgin, Rhea Silvia, has The Monarchy is overthrown and replaced The Republic grows corrupt, A second triumvirate is formed of Octavius Caesar twins fathered by the god Mars. The stolen by a Republic, a government by the people, begins to flounder and decay. (Julius Caesar’s great-nephew), Marcus Lepidus, and and abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, headed by two consuls elected annually by the A triumvirate is formed of Mark Antony. In 27 BC, Mark Antony loses the Battle are fed by a woodpecker and nursed by a citizens and advised by a senate. A constitution Pompey the Great, Marcus of Actium and kills himself, Lepidus is exiled, and the she-wolf in a cave, the Lupercal. They grow gradually develops, centered on the principles of Crassus, and Julius Caesar. young Caesar becomes Augustus Caesar, Exalted One. up, found a city, argue, then Romulus kills a separation of powers and checks and balances. Remus and names the city Rome. OR it was All public offices are limited to one year. In 49 BC, Caesar crosses the Rubicon and is founded by Aeneas about this time. It is appointed temporary dictator three times; on ruled by kings for almost 250 years. -

Expression “Loco Filiae” in Gaius' Institutes

ARTICLES 1SOME CONSIDERATIONS ON THE EXPRESSION “LOCO FILIAE” IN GAIUS’ INSTITUTES Carlos Felipe Amunátegui Perelló* Patricio-Ignacio Carvajal Ramírez** Key words: Manus; potestas; mancipium; Gaius 1 Introduction The expression “loco filiae” that Gaius uses to describe the position of the wife in manu has led a significant number of scholars to the firm belief thatmanus and patria * Professor of Roman law, Pontificia Universidad Católica, Chile. This article is part of the Conicyt Research Project Anillos de Instigación Asociativa SOC 1111 and Fondecyt Regular 1141231. ** Professor of Roman law, Pontificia Universidad Católica, Chile. This article is part of the Conicyt Research Project Anillos de Instigación Asociativa SOC 1111 and Fondecyt Regular 1141231. Fundamina DOI: 10.17159/2411-7870/2016/v22n1a1 Volume 22 | Number 1 | 2016 Print ISSN 1021-545X/ Online ISSN 2411-7870 pp 1-24 1 CARLOS FELIPE AMUNÁTEGUI PERELLÓ AND PATRICIO-IGNACIO CARVAJAL RAMÍREZ potestas were equivalent powers.1 Although the personal powers that a paterfamilias could exert over his descendants did not seem to match those that he could apply to his wife in manu, Gaius consistently uses the expression loco filiae to describe her position. The personal powers which a paterfamilias usually held in relation to his descendants, namely the vitae necisque potestas (the power to kill or let live), ius noxa dandi (the right to surrender the perpetrator of some pre-defined offences), and the ius vendendi (the right to sell them in mancipio), seem to have adjusted poorly to the position of a wife under manus. Although the possibility has been put forward that the husband had some kind of ius vitae necisque over his wife in manu,2 this notion remains controversial.3 Further, the possibility of selling one’s own wife or surrendering her after a noxal action is not supported by any ancient sources. -

Julius Caesar Free Download

JULIUS CAESAR FREE DOWNLOAD Orlando W Qualley Chair of Classical Languages and Chair of the Classics Department Philip Freeman | 416 pages | 14 May 2009 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9780743289542 | English | New York, NY, United States Timeline Of the Life of Gaius Julius Caesar Find out more about page archiving. We strive for accuracy and fairness. And he granted citizenship to a number of foreigners. Few Romans would have chosen young Julius Caesar ca —44 B. Despite the reprieve, Caesar left Rome, joined the army and earned the prestigious Julius Caesar Crown for his courage at the Siege of Mytilene in 80 Julius Caesar. Aristotle Philosopher. As a result of his debt Caesar turned to the richest man in Rome and possibly in history by some accountsMarcus Licinius Crassus. The difference between a republic and an empire is Julius Caesar loyalty of Julius Caesar army Julius Caesar. It has also provided many well-known quotes — Julius Caesar to Shakespeare, not Caesar — including:. A people known for their military, political, and social institutions, the ancient Romans conquered vast amounts of land in Europe and northern Africa, built roads and aqueducts, and spread Latin, their language, far and wide. He remained close to his mother, Aurelia. Scipio Africanus was a talented Roman general who commanded the army Julius Caesar defeated Hannibal in the final battle of the Second Punic War in B. Sign in. Caesar drove Pompey out of Italy and chased him to Greece. The Julii Caesares traced their lineage back to the goddess Venusbut the family was not snobbish or conservative-minded. Around the time of his Julius Caesar death, Caesar made a concerted effort to establish key alliances with the country's nobility, with whom he was well-connected. -

Aguirre-Santiago-Thesis-2013.Pdf

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SIC SEMPER TYRANNIS: TYRANNICIDE AND VIOLENCE AS POLITICAL TOOLS IN REPUBLICAN ROME A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in History By Santiago Aguirre May 2013 The thesis of Santiago Aguirre is approved: ________________________ ______________ Thomas W. Devine, Ph.D. Date ________________________ ______________ Patricia Juarez-Dappe, Ph.D. Date ________________________ ______________ Frank L. Vatai, Ph.D, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii DEDICATION For my mother and father, who brought me to this country at the age of three and have provided me with love and guidance ever since. From the bottom of my heart, I want to thank you for all the sacrifices that you have made to help me fulfill my dreams. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Frank L. Vatai. He helped me re-discover my love for Ancient Greek and Roman history, both through the various courses I took with him, and the wonderful opportunity he gave me to T.A. his course on Ancient Greece. The idea to write this thesis paper, after all, was first sparked when I took Dr. Vatai’s course on the Late Roman Republic, since it made me want to go back and re-read Livy. I also want to thank Dr. Patricia Juarez-Dappe, who gave me the opportunity to read the abstract of one of my papers in the Southwestern Social Science Association conference in the spring of 2012, and later invited me to T.A. one of her courses. -

Julius Caesar

Working Paper CEsA CSG 168/2018 ANCIENT ROMAN POLITICS – JULIUS CAESAR Maria SOUSA GALITO Abstract Julius Caesar (JC) survived two civil wars: first, leaded by Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius; and second by himself and Pompeius Magnus. Until he was stabbed to death, at a senate session, in the Ides of March of 44 BC. JC has always been loved or hated, since he was alive and throughout History. He was a war hero, as many others. He was a patrician, among many. He was a roman Dictator, but not the only one. So what did he do exactly to get all this attention? Why did he stand out so much from the crowd? What did he represent? JC was a front-runner of his time, not a modern leader of the XXI century; and there are things not accepted today that were considered courageous or even extraordinary achievements back then. This text tries to explain why it’s important to focus on the man; on his life achievements before becoming the most powerful man in Rome; and why he stood out from every other man. Keywords Caesar, Politics, Military, Religion, Assassination. Sumário Júlio César (JC) sobreviveu a duas guerras civis: primeiro, lideradas por Cornélio Sula e Caio Mário; e depois por ele e Pompeius Magnus. Até ser esfaqueado numa sessão do senado nos Idos de Março de 44 AC. JC foi sempre amado ou odiado, quando ainda era vivo e ao longo da História. Ele foi um herói de guerra, como outros. Ele era um patrício, entre muitos. Ele foi um ditador romano, mas não o único. -

Roman History the LEGENDARY PERIOD of the KINGS (753

Roman History THE LEGENDARY PERIOD OF THE KINGS (753 - 510 B.C.) Rome was said to have been founded by Latin colonists from Alba Longa, a nearby city in ancient Latium. The legendary date of the founding was 753 B.C.; it was ascribed to Romulus and Remus, the twin sons of the daughter of the king of Alba Longa. Later legend carried the ancestry of the Romans back to the Trojans and their leader Aeneas, whose son Ascanius, or Iulus, was the founder and first king of Alba Longa. The tales concerning Romulus’s rule, notably the rape of the Sabine women and the war with the Sabines, point to an early infiltration of Sabine peoples or to a union of Latin and Sabine elements at the beginning. The three tribes that appear in the legend of Romulus as the parts of the new commonwealth suggest that Rome arose from the amalgamation of three stocks, thought to be Latin, Sabine, and Etruscan. The seven kings of the regal period begin with Romulus, from 753 to 715 B.C.; Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, from 534 to 510 B.C., the seventh and last king, whose tyrannical rule was overthrown when his son ravished Lucretia, the wife of a kinsman. Tarquinius was banished, and attempts by Etruscan or Latin cities to reinstate him on the throne at Rome were unavailing. Although the names, dates, and events of the regal period are considered as belonging to the realm of fiction and myth rather than to that of factual history, certain facts seem well attested: the existence of an early rule by kings; the growth of the city and its struggles with neighboring peoples; the conquest of Rome by Etruria and the establishment of a dynasty of Etruscan princes, symbolized by the rule of the Tarquins; the overthrow of this alien control; and the abolition of the kingship. -

Roma'nin Kaderini Çizmiş Bir Ailenin

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANA BİLİM DALI ESKİÇAĞ TARİHİ BİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ CORNELII SCIPIONES: ROMA’NIN KADERİNİ ÇİZMİŞ BİR AİLENİN TARİHİ VE MİRASI Mehmet Esat Özer 2501151298 Tez Danışmanı Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Gürkan Ergin İSTANBUL-2019 ÖZ CORNELII SCIPIONES: ROMA’NIN KADERİNİ ÇİZMİŞ BİR AİLENİN TARİHİ VE MİRASI MEHMET ESAT ÖZER Scipio ailesinin tarihi neredeyse Roma Cumhuriyeti’nin kendisi kadar eskidir. Scipio’lar Roma Cumhuriyeti’nde yüksek memuriyet görevlerinde en sık yer almış ailelerinden biri olup yükselişleri etkileyicidir. Roma’nın bir varoluş mücadelesi verdiği Veii Savaşları’ndan yükselişe geçtiği Kartaca Savaşları’na Roma Cumhuriyet tarihinin en kritik anlarında sahne alarak Roma’nın Akdeniz Dünyası’nın egemen gücü olmasına katkıda bulunmuşlardır. Aile özellikle Scipio Africanus, Scipio Aemilianus gibi isimlerin elde ettiği başarılarla Roma aristokrasisinde ön plana çıkarak Roma’nın siyasi ve askeri tarihinin önemli olaylarında başrol oynamıştır. Bu tezde Scipio ailesi antik yazarların eserleri ve arkeolojik veriler ışığında incelenerek ailenin geçmişi; siyasi, sosyal, kültürel alanlardaki faaliyetleriyle katkıları ve Roma’nın emperyal bir devlete dönüşmesindeki etkileri değerlendirilecektir. Konunun kapsamı sadece ailenin Roma Cumhuriyet tarihindeki yeriyle sınırlı kalmayıp sonraki dönemlerde de zamanın şartlarına göre nasıl algılandığına da değinilecektir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Cornelii Scipiones, Scipio, Roma Cumhuriyeti, Aristokrasi, Scipio Africanus, Scipio Aemilianus, Kartaca, Emperyal.