Homelessness 2018 Enumeration Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fire Department Members in Good Standing Addington Highlands Fire

Fire Department Members in good standing Addington Highlands Fire Adelaide Metcalfe Fire Department Adjala-Tosorontio Fire Department Y Ajax Fire Y Alberton Fire Alfred & Plantagenet Y Algonquin Highlands Fire Alnwick/Haldlmand Fire Y Amherstburg Fire Department Y Arcelor-Mittal Dofasco Argyle Fire Armstrong Fire Arnprior Fire Arran Elderslie (Chelsey) Fire Arran Elderslie (Paisley) Fire Arran Elderslie (Tara) Fire Asphodel-Norwood Fire Assiginack Fire Athens Fire Y Atikokan Fire Augusta Fire Y Aviva Insurance Canada Y Aweres Fire Aylmer Fire Department Y Baldwin Fire Barrie Fire & Emergency Services Y Batchawana Bay Fire Bayfield Fire Bayham Fire & Emergency Services Y Beausoleil Fire Beckwith Twp. Fire Belleville Fire Y Biddulph-Blanshard Fire Billings & Allan Fire Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport Black River Matheson Fire Blandford - Blenheim Fire Blind River Fire Bonfield Volunteer Fire Department Bonnechere Valley Fire Department Bracebridge Fire Department Y Bradford West Gwillinbury Fire & Emergency Services Y Brampton Fire Department Y Brantford Fire Department Y Brighton District Fire Department Britt Fire Department Brock Twp. Fire Department Y Brockton Fire Department Y Brockville Fire Department Y Brooke-Alvinston District Fire Department Y Bruce Mines Bruce Mines Fire Department Y Bruce Power Brucefield Area Fire Department Brudenell, Lyndoch & Raglan Fire Department Burk's Falls & District Fire Department Y Burlington Fire Department Y Burpee & Mills Fire Department Caledon Fire & Emergency Services Y Callander Fire Department -

Railway Occurrence Report Cn North America

RAILWAY OCCURRENCE REPORT CN NORTH AMERICA DERAILMENT TRAIN NO. 302-27 MILE 56.7, RUEL SUBDIVISION NEAR WESTREE, ONTARIO 30 JANUARY 1994 REPORT NUMBER R94T0029 MANDATE OF THE TSB The Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act provides the legal framework governing the TSB's activities. Basically, the TSB has a mandate to advance safety in the marine, pipeline, rail, and aviation modes of transportation by: ! conducting independent investigations and, if necessary, public inquiries into transportation occurrences in order to make findings as to their causes and contributing factors; ! reporting publicly on its investigations and public inquiries and on the related findings; ! identifying safety deficiencies as evidenced by transportation occurrences; ! making recommendations designed to eliminate or reduce any such safety deficiencies; and ! conducting special studies and special investigations on transportation safety matters. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. However, the Board must not refrain from fully reporting on the causes and contributing factors merely because fault or liability might be inferred from the Board's findings. INDEPENDENCE To enable the public to have confidence in the transportation accident investigation process, it is essential that the investigating agency be, and be seen to be, independent and free from any conflicts of interest when it investigates accidents, identifies safety deficiencies, and makes safety recommendations. Independence is a key feature of the TSB. The Board reports to Parliament through the President of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada and is separate from other government agencies and departments. Its independence enables it to be fully objective in arriving at its conclusions and recommendations. -

Official Road Map of Ontario

o ojikitM L. ik N th W p ercyP L. Pitukupi r a a 14 o k 7 K 8 9 10 11 12 13 N 15 h Stone L. Onakawana w s 88° 87° 86° 85° 84° 83° 82° 81° a fi y k L. r o N c e w v e a i ka J R t Ara L. to C r s Abamasagi e t g g O er iv ic a L. wnin R Riv R m ro iv i D e C e O'Sullivan L R. l r t i R H t it F L. t F Jog L. l L e . ge O Marshall Rid i I R MISSINAIBI m R L. a A Ferland R g T Esnagami N ta a i t O Mud k b R i Wababimiga i a River b L. a i M v a in 50° ive e L. i R r ss A i r 50° Aroland gam River M Coral mb Auden Lower no O Ke r Otter Rapids 643 Twin ive A R b r 19 Nakina N i fe L. t e i Logan I. 9 v b Fleming i A i L. R b r i Upper e a ti Riv k b Onaman is Private road i Twin L. b L. a with public access E iv P Route privée Murchison I. Burrows Chipman à accès public North 584 r fe L. L. e Wind n iv 62 a FUSHIMI LAKE i R L. w r a e Fraserdale s v Pivabiska . -

Geology of Foleyet and Ivanhoe Townships; Ontario Geological Survey, Open File Report 5851, 42P

ISBN 0-7778-1337-8 THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

Chapleau-Foleyet Sheet

THESE TERMS GOVERN YOUR USE OF THIS DOCUMENT Your use of this Ontario Geological Survey document (the “Content”) is governed by the terms set out on this page (“Terms of Use”). By downloading this Content, you (the “User”) have accepted, and have agreed to be bound by, the Terms of Use. Content: This Content is offered by the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) as a public service, on an “as-is” basis. Recommendations and statements of opinion expressed in the Content are those of the author or authors and are not to be construed as statement of government policy. You are solely responsible for your use of the Content. You should not rely on the Content for legal advice nor as authoritative in your particular circumstances. Users should verify the accuracy and applicability of any Content before acting on it. MNDM does not guarantee, or make any warranty express or implied, that the Content is current, accurate, complete or reliable. MNDM is not responsible for any damage however caused, which results, directly or indirectly, from your use of the Content. MNDM assumes no legal liability or responsibility for the Content whatsoever. Links to Other Web Sites: This Content may contain links, to Web sites that are not operated by MNDM. Linked Web sites may not be available in French. MNDM neither endorses nor assumes any responsibility for the safety, accuracy or availability of linked Web sites or the information contained on them. The linked Web sites, their operation and content are the responsibility of the person or entity for which they were created or maintained (the “Owner”). -

Presentation Chapleau Council

Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB Presentation to: Municipality of Chapleau Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB Thank you for this opportunity to present on how the Paramedic Services relate to your community Topics of discussion 1. A perspective of Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB 2. The Paramedic Services Department 3. Call Volumes and Staffing 4. Challenges & Opportunities: I. Regionalized Health Care II. Long Distance Transport Options III. Non-urgent Activities 5. Questions? DSB Coverage Area • Encompasses the Districts of Manitoulin and Sudbury (excluding the City of Greater Sudbury). • An area of over 45,000 sq. km • Larger than 115 Countries in the World • 12 EMS Stations • Northern Coverage Chapleau (12/7 on site and 12/7 on call). Foleyet (10/7 on site and 14/7 on call) • Chapleau max coverage of one hours in all directions. From To Distance (km) Time (hh:mm) Toronto Detroit 393 4:16 Toronto Sudbury 385 4:55 Distance Toronto Ottawa 411 4:33 Challenges Toronto Montreal 544 6:18 Chapleau Sudbury 410 5:15 Travel from Chapleau to Timmins is 2 hours and 39 Chapleau Timmins 202 2:39 minutes one way (202 KMs) Wawa Sault Ste. 224 2:27 Travel from Chapleau to Marie Sudbury is 5 hours and 15 minutes (410KMs) The MOHLTC/Ornge have an arbitrary rule that non-urgent patients will not be moved by air ambulance where the one way distance is less than 240KM. The rule does not consider road conditions, nor does it consider travel distance. Wawa is granted exception, while Chapleau is not. Key Paramedic Responsibilities Provide land ambulance operations in a seamless manner to the community. -

Ontario Early Years Child and Family Centre Plan

Manitoulin-Sudbury District Services Board Ontario Early Years Child and Family Centres (OEYCFC) OEYCFC Plan and Local Needs Assessment Summary 2017 Geographic Distinction Reference The catchment area of the Manitoulin-Sudbury District Services Board (Manitoulin- Sudbury DSB) includes 38 communities, towns and villages and covers a distance that spans over 42,542 square kilometres. The communities, towns and villages are represented by 18 municipal jurisdictions and 2 unorganized areas, Sudbury Unorganized North Part and Manitoulin Unorganized West Part. The catchment area of the Manitoulin- Sudbury DSB is a provincially designated area for the purposes of the delivery of social services. The municipalities represented by the Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB are: Baldwin, Espanola, Nairn and Hyman, Sables-Spanish River, Assiginack, Billings, Burpee and Mills, Central Manitoulin, Cockburn Island, Gordon/Barrie Island, Gore Bay, Northeastern Manitoulin and the Islands, Tehkummah, French River, Killarney, Markstay- Warren, St. Charles and Chapleau. The municipalities in the Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB catchment area are commonly grouped into four main areas or regions, known as LaCloche, Manitoulin Island, Sudbury East and Sudbury North. The Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB catchment area does not include First Nations territories. Data for this report has been derived, for the most part, from Statistics Canada. We have used the most recent data (2016) whenever possible and have used 2011 data where the 2016 data is not yet available. From a Statistics Canada perspective, data for the catchment area of the Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB falls within two Census Divisions, Manitoulin District and Sudbury District. Manitoulin District and Sudbury District Census Divisions: The Manitoulin District – otherwise known as Manitoulin Island – includes 10 census subdivisions containing 14 communities, town and villages, and one unorganized territory. -

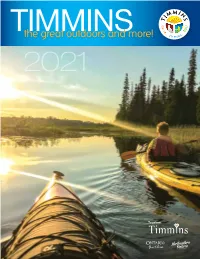

The Great Outdoors and More! 2021 Publisher/Editor: All Information in This Guide Was Deemed How to Get Here

TIMMINSthe great outdoors and more! 2021 Publisher/Editor: All information in this guide was deemed How to Get Here ............................... 2 TOURISM TIMMINS accurate at the time of printing. Canoe, Kayak & SUP Routes ............. 4 220 Algonquin Blvd. East All price references are subject to change. Timmins, Ontario P4N 1B3 Should you decide to take a canoe trip Biking and Hiking Trails .................... 6 705.360.2619 | 800.387.8466 based on information presented in this Fax: 705.360.2682 database, it is essential that you purchase Golfing ............................................. 8 an approved Government of Ontario [email protected] topographical map available from local Parks and Campgrounds ................... 8 tourismtimmins.com hunting and fishing tackle businesses. You should also be familiar with basic Provincial and Municipal Parks ......... 9 Editorial Contributors: compass and map reading skills. Users Arts, Culture and Heritage ...............12 Diane Armstrong, Karen Bachman, are also reminded that access routes and Guy Lamarche, Lorraine Cantin, trails are in a natural setting; therefore Indigenous Murals ...........................16 they may be altered by natural conditions Antoine Garwah, Marnie Lapierre, and may contain dangerous sections. Indigenous Experiences ...................17 Lacey Rigg Many of the canoe routes described in this database require advanced canoeing Competitive Events ..........................18 Tourist Information: and survival skills. It is imperative novice Timmins Convention -

This Document Was Retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act E-Register, Which Is Accessible Through the Website of the Ontario Heritage Trust At

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. t 'l ' TELEPHONE (519) 482-3997 C. C. Q"ooto" 23 ALBERT STREET CL"f,-J"'orr"., P.O. BOX 400 e'C. gr\' CLINTON, ONTARIO J4rr. -,11. J'll-'-'1,#,r,u, (Dt NOM 1LO ty CL" fn- J"rot r,.t 1t " "HOME OF NADAR IN CANADA" IN THE MATTER OF THE ONTARIO HERITAGE ACT I9?4, S. 0. 1980, Chapter 33?. AND ]N THE MATTER OF THE LANDS AND PREMISES AT THE FOLLOWTNG MUNICTPAL ADDRESSES IN THE PROVINCE OF ONTARTO. NOTICE OF INTENTION TO DESIGNATE To: Ontari-o Herltage Foundation, 77 Bloor St. West, Toronto, Ontario. MZA zRg TAKE NOTICE that the Council of the Corporation of the Town of Clinton intends to designate the properties, incl-ud.ing lands and buildings, at the,following municipal ad.dresses as prdperties of architectural and/or histoiical interest under part- rv of the 0ntario Heritage Act, I9?4, R. S. O. Chapter 332. (a) The Former Molson's Bank Building / 23-25 Rattenbury St. East, (b) The Faryan-Rance House 4O nattenbury St. East, (c) The Peacock-McMurray House IJ! Ontario Street, / . (d) The C. N. School on Wheel_s No. 15089 Sloman Park, Victoria Terrace. ,./ Reasons for the proposed designation of the above properties are enclo sed. -

Official Road Map of Ontario

s A ika u at p b s a ) i a 13 14t 15 16 18 K g i p b O e o i d 82° ) 81° LITTLE ABITIBI 80° 79° h e r d è n i v u i r ( o r Pierre G 73 RENÉ Island Falls e L. N M BRUNELLE r 120 pasatika è i a v t i t r a Harty ( g Little a G Val Rita m Wurtele Abitibi 581 i Kapuskasing 22 fe10 634 L. G fe Traversier Moonbeam Fauquier Ferry 652 40 Smooth Rock fe Falls GREENWATER Grégoires 579 Clute Mill 28 Clutefe 32 20Kilometres 0 Miles 20 Driftwood 636 49° 668 fe 20kilomètres 49° 11 0 milles 20 fe 7 15 18 14 8 652 r 16 e fe Saganash 10 v i 574 R L. Hunta Taykwafe 49° R Cochrane 111 i Tagamou Nation v po A e b r 11 49 it ib i LAKE 75 dc Macamic Tunis La Sarre g ABITIBI-DE TROYES n i River s Nellie Lake (Lac a 111 N 393 a 67 Iroquois Falls B T B po po t 655 A I I I r dc e fe Porquis Junction 101 v Abitibi) po Ri 10 Monteith Barbers Bay Val Gagné Wahgoshig H 14 R. Connaught 577 10 First Nation fe Matheson 36 23 388 Hoyle 28 po Duparquet R. 17 101 QUÉBEC Flying Post Shillington10 6 15 23 572 dc 395 R Timmins fe po Elsas Porcupine KETTLE LAKES Holtyre . SchumacherSouth Porcupine Ramore 101 H e 672 g o a i po h o t fe 24 Night n h o ESKER a d k . -

Directory of Ontario Jurisdictions Cross-Referenced by Health Unit

Directory of Ontario Jurisdictions Cross- referenced by Health Unit © Produced and compiled by the Association of Local Public Health Agencies, 2008 Public Health Unit Names Updated 2020 City Health Unit Region ABBEY SUDBURY NORTH EAST ABBOTSFORD PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ABBOTT TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABERARDER LAMBTON SOUTH WEST ABERDEEN TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABERDEEN GREY-BRUCE SOUTH WEST ABERDEEN ADDITIONAL ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABERFELDY LAMBTON SOUTH WEST ABERFOYLE WELLINGTON-DUFFERIN CENTRAL WEST ABIGO TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABINGDON NIAGARA CENTRAL WEST ABINGER KINGSTON EASTERN ABITIBI CANYON PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ABIWIN NORTHWESTERN NORTH WEST ABNEY TP SUDBURY NORTH EAST ABOTOSSAWAY TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABRAHAM TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABREY TP THUNDER BAY NORTH WEST ACADIA TP SUDBURY NORTH EAST ACANTHUS NORTH BAY NORTH EAST ACHESON TP SUDBURY NORTH EAST ACHIGAN ALGOMA NORTH EAST ACHILL SIMCOE CENTRAL EAST ACHRAY NORTH BAY NORTH EAST ACOUCHICHING NORTH BAY NORTH EAST ACRES TP PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ACTINOLITE HASTINGS EASTERN ACTON TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ACTON HALTON CENTRAL WEST ACTON CORNERS LEEDS EASTERN ADAIR TP PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ADAMS PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ADAMSON TP THUNDER BAY NORTH WEST AMSVILLE GREY-BRUCE SOUTH WEST ADANAC TP PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ADDINGTON HIGHLANDS TP KINGSTON EASTERN ADDISON TP SUDBURY NORTH EAST ADDISON LEEDS EASTERN ADELAIDE MIDDLESEX SOUTH WEST ADELAIDE METCALFE TP MIDDLESEX SOUTH WEST ADELARD RENFREW EASTERN ADIK ALGOMA NORTH EAST ADJALA SIMCOE CENTRAL EAST ADJALA-TOSORONTIO TP SIMCOE CENTRAL EAST ADMASTON RENFREW EASTERN -

10-Year Housing and Homelessness Plan

2014 Moving Forward A Plan to Address Housing and Homelessness within the Manitoulin- Sudbury District Services Board Catchment Area over the Next 10 Years Social Planning Council of Sudbury May 1, 2013 Revised by Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB February 27, 2014 1 Contributors to the Plan: Mary Hanna (M.A.), Social Planning Council of Sudbury Annette Reszczynski (M.A.), Social Planning Council of Sudbury Janet Gasparini, Social Planning Council of Sudbury Danielle Beaulieu, Laurentian University Lynn O’Farrell (M.Sc), Social Planning Council of Sudbury Special Thanks to Donna Moroso and Rhonda McCauley from the Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB for all of their input and guidance. This plan is intended for use by the Manitoulin-Sudbury District Services Board (Manitoulin-Sudbury DSB). 2 Table of Contents Contributors to the Plan: ......................................................................................................... 1 Geographic Distinctions Reference ........................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction .............................................................................................................................16 Geography of the Manitoulin-Sudbury District .....................................................................17 Housing Instability and Homelessness in Northern Rural Communities: An Overview ....20 Definition of Homelessness