County Durham, the Oldest Known Sword Dance Play Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of St Cuthbert'

A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham by Ruth Robson of St Cuthbert' 1. Market Place Welcome to A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham, part of Durham Book Festival, produced by New Writing North, the regional writing development agency for the North of England. Durham Book Festival was established in the 1980s and is one of the country’s first literary festivals. The County and City of Durham have been much written about, being the birthplace, residence, and inspiration for many writers of both fact, fiction, and poetry. Before we delve into stories of scribes, poets, academia, prize-winning authors, political discourse, and folklore passed down through generations, we need to know why the city is here. Durham is a place steeped in history, with evidence of a pre-Roman settlement on the edge of the city at Maiden Castle. Its origins as we know it today start with the arrival of the community of St Cuthbert in the year 995 and the building of the white church at the top of the hill in the centre of the city. This Anglo-Saxon structure was a precursor to today’s cathedral, built by the Normans after the 1066 invasion. It houses both the shrine of St Cuthbert and the tomb of the Venerable Bede, and forms the Durham UNESCO World Heritage Site along with Durham Castle and other buildings, and their setting. The early civic history of Durham is tied to the role of its Bishops, known as the Prince Bishops. The Bishopric of Durham held unique powers in England, as this quote from the steward of Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham from 1284-1311, illustrates: ‘There are two kings in England, namely the Lord King of England, wearing a crown in sign of his regality and the Lord Bishop of Durham wearing a mitre in place of a crown, in sign of his regality in the diocese of Durham.’ The area from the River Tees south of Durham to the River Tweed, which for the most part forms the border between England and Scotland, was semi-independent of England for centuries, ruled in part by the Bishop of Durham and in part by the Earl of Northumberland. -

Creative Media Production Enrichment - Js

CREATIVE MEDIA PRODUCTION ENRICHMENT - JS Creative question: What makes the North East Unique The focus of the project is to use a creative enquiry approach based around an open question. This will generate an agreed outcome that is entirely student led which will use different forms of media to showcase their findings. Teaching and Learning Role As teaching and Learning Lead, my role will be to advise and support on the programme development, act as a critical friend to challenge thinking and practice, analyse pedagogy and effective practice. I will engage in initial ideas, and help pupils to develop and become confident in managing a social enterprise event. I will review the social enterprise work with staff, outside visitors, pupils and parents. Date Activity Outcome Week 1 Key Question What makes the North Students take on the role of investigators and East Unique? brainstorm answers PPT mystery where is the Landmark? They solve clues to look at Landmarks in the What do we want to get out of a North East. project? They share their knowledge and come up What are our strengths? with a plan. Drama games/warm up activities What do we know about the North East? How Discussion of what an enquiry is, can we find out more? What is important to children to come up with the ideas people in the North East? How can we find after looking at information. They ask out? questions to extend their knowledge. They generate their own ideas and explore all the possibilities Week 2 Investigate and sketch features of the Students (with input from the teacher) decide North East which landmarks are a priority to visit. -

Washington Heritage Offer - Discussion Paper

REPORT FOR WASHINGTON AREA COMMITTEE 7 JANUARY 2010 REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR CITY SERVICES WASHINGTON HERITAGE OFFER - DISCUSSION PAPER 1.0 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1.1 The purpose of the report is for Members of the Washington Area Committee to discuss and recommend ways forward in relation to the Heritage agenda within Washington, in order that projects can be investigated and developed for the future. 2.0 BACKGROUND 2.1 Washington is located in the west of Sunderland and is divided into small villages or districts, with the original settlement being named Washington Village. Washington became a new town in 1964 and a part of Sunderland in 1974. Washington is now a diverse town offering wonderful countryside views, fascinating history, heritage and leisure attractions. 3.0 CONTEXT 3.1 Heritage is an area of continuing growth both across the region and for the City of Sunderland. Sunderland has a distinct heritage and there is a strong sense of pride across the city. This pride is based on our character and our traditions, including the distinct identity of specific communities and the cultural traditions of our people. A successful nomination which is currently being developed for World Heritage Status would allow the city to become a cultural heritage landmark as one of three World Heritage Sites across the region and 27 sites across the UK, allowing the city to prosper in areas such as economic development and tourism. 3.2 Heritage for the city is managed and delivered through the City Services Directorate, with two part-time heritage officers working to deliver the Heritage agenda. -

Fatfield Circular Drummond

Key points of interest E) Arts Centre Washington Heritage Trails Washington Area The Arts Centre is a converted 19th A) Fatfield Bridge century farm, a ruin rescued at the time Designed by D. Balfour of Houghton- of the development of the new town in le-Spring, this bridge was built in 1889 1972. Originally called Biddick Farm at a cost of £8000. It was officially Arts Centre, it has gone through opened on 29 January 1890 by the several incarnations to become a 3rd Earl of Durham. vibrant multi-arts centre with a theatre, 6 B) Girdle Cake Cottage gallery, rehearsal rooms, artists studios, Walk The Biddick Pumping Station stands recording studio, café and award on the site of Girdle Cake Cottage. This winning bar. It is now owned and quaintly named dwelling was reputedly managed by Sunderland City Council. the refuge of the Earl of Perth, James F) Worm Hill Fatfield Circular Drummond. The Earl is said to have According to local legend this is the hill taken sanctuary here after the Jacobite which the Lambton Worm wrapped Walk Distance & Time: Army was defeated by the Duke of itself around after roaming the 2.9 miles or 4.8km Cumberland’s Government forces at surrounding countryside, terrorising the the Battle of Culloden in 1746. locals and devouring the cows and 1 hour (approx) C) Victoria Viaduct sheep. The summit offers fine views of This bridge is one of the most the semi-natural ancient woodlands of Start and Finish Point: impressive stone viaducts in Britain. the Wear corridor, with Penshaw Named after Queen Victoria, the final Monument above. -

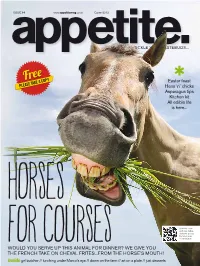

Horses for Courses Scan This Code

ISSUE 14 www.appetitemag.co.uk Easter 2013 T ICKLE YOUR TASTEBUDS... Easter feast Hens ‘n’ chicks Asparagus tips Kitchen kit All edible life is here... Horses Scan this code with your mobile device to access the latest news for courses on our website WOO ULD Y U seRVE UP THIS ANIMAL FOR DINNER? WE GIVE YOU THE FRENCH TAKE ON CHEVAL FRITES...FROM THE HORSE’S MOUTH! inside girl butcher // lunching under Marco’s eye // down on the farm // art on a plate // just desserts Appetite Advert_Layout 1 08/03/2013 15:32 Page 1 PLACE YOUR Editor, fazed by the fuss over ORDER FREE STAY horsemeat, ponders the wisdom 4 CLUB Great places, great offers of what we eat. If horse, why 6 FEED...BACK FRIDAYS not dog, after all? Reader recipes and news 7 it’s a dATE AT THE NEW Fab places to tour and taste There I was, minding my own business, trying to source a supplier so that he can NORTHUMBRIA HOTEL languishing of a Sunday morning on the serve cheval steak frites. Our other new 8 GIRL ABOUT TOON sofa under something called a Slanket columnist, butcher Charlotte Harbottle, Our lady Laura’s adventures in food (a blanket with foot and hand pockets; along with farmers and farm shop strange, but a greatly efficacious hangover proprietors, tells us that the scandal has at 10 LUNCH cure) when a rant began. “Horse! Horse! least made us all more conscious of the A feast at The Lambton Worm Dine at Louis' Jesmond on any Friday evening for two people & if you spend It’s like eating your dog. -

Lambton Arms to Pelton Fell Railway Walk

Lambton Arms to Pelton Fell Railway Walk Today your amended walk, being led by Moira Foster was to be along the C2C cycle track starting behind the Lambton Worm pub and heading towards Pelton Fell. It’s a walk we have done many times and Moira has taken a few photographs to remind us of the route. Today wouldn’t have been the first time it’s been very muddy getting on to the track. The course of the former Stanhope and Tyne Railway of 1834 through Pelton Fell, Stella Gill and South Pelaw which served local mines is now occupied by part of a long distance cycleway (the C2C cyclepath) and footpath noted for unusual sculptures that adorn the route. John Grimshaw , director and chief engineer of Sustrans had the vision and foresight to redevelop these redundant facilities as long distance cycle paths as future important resources, as recreational, social and green links , connecting communities rural and urban as well as facilitating access to our countryside again. Near Stella Gill is an appropriately named sculpture called King Coal that was unveiled in 1992 at about the time the last mines were closing in County Durham. This impressive sculpture, designed by an artist called David Kemp features the enormous face of a bearded man who gazes outward in the direction of the distant Penshaw Monument. He is made from recycled bricks, mining shovels and a colliery fan impeller and we get the overall impression that the remnants of some old colliery building have strangely transformed by their own design into a king who now keeps watch over his lost kingdom. -

City of Sunderland Landscape Character Assessment

City of Sunderland Landscape Character Assessment Prepared by LUC for Sunderland City Council September 2015 Project Title: City of Sunderland Landscape Character Assessment Client: Sunderland City Council Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by Principal 1 23 June 2014 Outline draft LUC PDM SCO 2 15 October Draft report LUC PDM SCO 2014 3 9 July 2015 Final draft report LUC PDM SCO 4 7 September Final report LUC PDM SCO 2015 H:\1 Projects\60\6074 Sunderland LCA\B Project Working\REPORT\Sunderland LCA v4 20150907.docx City of Sunderland Landscape Character Assessment Prepared by LUC for Sunderland City Council September 2015 Planning & EIA LUC EDINBURGH Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd 28 Stafford Street Registered in England Design London Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning Edinburgh Bristol Registered Office: Landscape Management EH3 7BD Glasgow 43 Chalton Street Ecology Tel: 0131 202 1616 London NW1 1JD LUC uses 100% recycled paper Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 Contents 1 Introduction 10 Background 10 Study Area 10 Approach 11 Glossary 12 2 Evolution of the Landscape 16 Introduction 16 Physical influences 17 Human influences 18 The modern landscape 21 3 Landscape Classification 26 Introduction 26 4 Landscape Character Types and Areas 30 Introduction 30 LCT 1: Coalfield Ridge 31 Description 31 Guidance and strategy 33 LCT 2: Coalfield Lowland Terraces 36 Description 36 Guidance and strategy 42 LCT 3: Incised Lowland Valley 46 Description 46 Guidance and -

Penshaw Monument

LOCAL STUDIES CENTRE FACT SHEET NUMBER 14 Penshaw Monument A brief history On the summit of Penshaw Hill is the Monument, built in honour of John George Lambton, the first Earl of Durham. Penshaw Monument dominates the skyline and can be seen for miles around, from County Durham, Wearside and Tyneside. It overlooks Herrington County Park on the south side and Washington Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust on the north side. Penshaw comes from the old British word pen, meaning hill and shaw describes a wooded area. The foundation stone was laid on Wednesday 28 August 1844, by Thomas, Earl of Zetland, in the presence of a large crowd, attended by about 400 members of the Provincial Grand Lodges of Freemasons. About £6,000 was raised by public subscription, which was used to build the Monument. However funding ran out and the roof and interior walls were never added. In 1988 when Sunderland City Council invested £50,000 in floodlights, the dramatic play of light among the columns added to The structure the visual effect. The Grade l listed monument, built in the form of a Greek temple, stands 136 metres above sea level. It The monument is now in the care of the National is based on the design of the Theseion, the Temple of Trust. Hephaestus, in Athens. It was designed by Newcastle architects John and Benjamin Green and built by Thomas Pratt of Sunderland. The Monument is made of gritstone from the quarries of the then Marquess of Londonderry. Steel pins and brackets held the gritstone blocks together, but over the years these deteriorated. -

Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Phd

Linguistic Identity in Nineteenth-Century Tyneside Dialect Songs by Rodney Hermeston Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds School of English March 2009 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement 1 Acknowledgements I wish to give particular thanks to my supervisors, David Fairer, Anthea Fraser Gupta and Alison Johnson. Acknowledgements also go to Clive Upton. Thanks to Katie Wales, Joan Beal, Nikolas Coupland, Emma Moore, Andrew Walker, Judith Murphy and Charles Phythian-Adams. All of these scholars made manuscripts and conference papers available to me. I am extremely grateful to Katie Wales for commenting upon parts of my work. Thanks also to Julia Snell. In addition I wish to acknowledge the support given by The Brotherton Trust to assist in the use of rare book collections in various libraries of northern England. I am grateful to my family and friends, and special thanks are due to Bryan and Shirley Matthews. Finally I am extremely grateful for the support (and patience) of Sarah Vaughan. ii Abstract This thesis examines the social meanings and identities conveyed by the use of local dialect in nineteenth-century Tyneside song. It is deliberately a hybrid of literary and linguistic approaches, and this dual methodology is used to raise questions about some of the categorical assumptions that have underpinned much previous discussion of this kind of material. -

Northern Saints Trail the Way of Learning Walk Leaflet

The Northern Way of Saints Trails Learning Jarrow - Sunderland - Durham Jarrow – Cleadon – Whitburn – Roker – The Christian Monkwearmouth – Sunderland – Penshaw Monument – Houghton-le-Spring – Chester-le-Street – crossroads of Great Lumley – Finchale Abbey – Crook Hall & Gardens the British Isles – Durham Cathedral Cleadon Mill Distance: 38 miles/61km The Way of Learning ‘Devote yourself to learn the sayings and doings of the men This, the most urban of the six Northern Saints Trails, might of old’ runs a quote from the Father of English History, the have less of the jaw-dropping countryside the North East Gain the ultimate enlightenment on The Way of Venerable Bede, around the atrium of a museum dedicated invariably exhibits, but it compensates by being jam-packed Learning as it takes you on the trail of England ’s to him at Jarrow Hall, near the start of The Way of Learning. with cultural eye-openers. The area has produced countless original scholar, the Venerable Bede, through a The quote is an apt metaphor for this walk. The route traces firsts (first English history book, England’s first stained glass, rich legacy of the North East’s foremost industry, the special places associated with Britain’s best-known first incandescent light bulb) and the route winds between scholar-monk the Venerable Bede, besides taking you on a example after example of the region’s exceptional inventiveness and innovation. journey to ground-breaking Roman discoveries (Arbeia, innovativeness over the centuries, and the museums that South Shields Roman Fort), the majestic medieval Finchale champion it. But one character stands out from The Way of Priory, where fascinating St Godric once attracted attention Learning in particular and that is the Venerable Bede. -

City of Sunderland Landscape Character Assessment

City of Sunderland Landscape Character Assessment Prepared by LUC for Sunderland City Council September 2015 LCT 2: Coalfield Lowland Terraces Description Location and extents 4.17 This LCT occurs within the Tyne and Wear Lowlands which occupy the eastern edge of the Durham Coalfield. The LCT is constrained to the north, east and south by the escarpment of the Durham Magnesian Limestone Plateau that rises sharply forming a distinct boundary between the two different bedrock types. The LCT extends south and west into County Durham covering an area of gently rolling topography that forms a transitional landscape between the Magnesian Limestone escarpment and the Wear Valley to the west. Key characteristics of the Coalfield Lowland Terraces 4.18 Key characteristics of the Coalfield Lowland Terraces LCT: • Lowland transitional landscape between the Magnesian Limestone escarpment to the east and Wear Valley to the west; • Underlying Carboniferous Coal Measures are masked by thick layers of glacial deposits; • The topography is gently rolling or flat in areas of boulder clay, with a more undulating terrain associated with river valleys, and with the remains of glacial moraines; • Agricultural land use is mixed but predominantly arable with semi-regular patterns of medium and large-scale fields bounded by low hawthorn hedges and pockets of recently planted woodland; • Former colliery workings and spoil heaps have now been reclaimed, with large tracts of recently restored land; • Fragmented by industrial and residential development, the landscape includes corridors of open space between settlements, often with urban fringe character; • Large industrial complexes and industrial estates are present; • Long and relatively open views across County Durham from the elevated foot slopes of the Limestone Escarpment to the west; these become less frequent towards the low lying Wear Valley.