Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wakefield Amateur Rowing Club, 1846 – C.1876

‘Jolly Boating Weather…’ Wakefield Amateur Rowing Club, 1846 – c.1876 Nowadays rowing is typically viewed as a socially elite sport: that of grammar schools, universities and gentlemen. Whilst this is true to a point, historically rowing has cut across boundaries of class as much as any other sport. During the nineteenth century most sports, including rowing, were divided into three broad classes – working or tradesmen who made their living on the water as watermen or boatman; middle class and gentlemen amateurs; and those who made their living from the sport, who came from the working or middle class. This last group, the professional sportsmen rowers, were the equivalent of today’s superstars from football or rugby; the Clasper family or James Renforth from Newcastle had a massive following as true working class heroes who made a living from their prize money and boat-making skills. Harry Clasper (1812 to 1870) and his brothers were some of the first superstar sportsmen of their day and also the earliest professional sportsmen – in other words they were able to live from their winnings and what we would now term sponsorship. Rowing races and regattas were seen by the middle and gentry classes as a polite summer entertainment and also as the off-season equivalent of horse racing, with prizes and wagers commonly running into several hundreds of pounds. Regattas were established in London on the Thames before 1825 – the ‘Lambeth,’ ‘Blackfriars’ and ‘Tower’ regattas were held that summer with prizes being as high as £25.1 Most towns with access to a good stretch of water established Rowing Clubs, generally as an ‘out door amusement’ but increasingly during the nineteenth century for the ‘improvement of the working classes’ and ‘bringing out the bone and muscle of our English youth.. -

North East History 39 2008 History Volume 39 2008

north east history north north east history volume 39 east biography and appreciation North East History 39 2008 history Volume 39 2008 Doug Malloch Don Edwards 1918-2008 1912-2005 John Toft René & Sid Chaplin Special Theme: Slavery, abolition & north east England This is the logo from our web site at:www.nelh.net. Visit it for news of activities. You will find an index of all volumes 1819: Newcastle Town Moor Reform Demonstration back to 1968. Chartism:Repression or restraint 19th Century Vaccination controversies plus oral history and reviews Volume 39 north east labour history society 2008 journal of the north east labour history society north east history north east history Volume 39 2008 ISSN 14743248 NORTHUMBERLAND © 2008 Printed by Azure Printing Units 1 F & G Pegswood Industrial Estate TYNE & Pegswood WEAR Morpeth Northumberland NE61 6HZ Tel: 01670 510271 DURHAM TEESSIDE Editorial Collective: Willie Thompson (Editor) John Charlton, John Creaby, Sandy Irvine, Lewis Mates, Marie-Thérèse Mayne, Paul Mayne, Matt Perry, Ben Sellers, Win Stokes (Reviews Editor) and Don Watson . journal of the north east labour history society www.nelh.net north east history Contents Editorial 5 Notes on Contributors 7 Acknowledgements and Permissions 8 Articles and Essays 9 Special Theme – Slavery, Abolition and North East England Introduction John Charlton 9 Black People and the North East Sean Creighton 11 America, Slavery and North East Quakers Patricia Hix 25 The Republic of Letters Peter Livsey 45 A Northumbrian Family in Jamaica - The Hendersons of Felton Valerie Glass 54 Sunderland and Abolition Tamsin Lilley 67 Articles 1819:Waterloo, Peterloo and Newcastle Town Moor John Charlton 79 Chartism – Repression of Restraint? Ben Nixon 109 Smallpox Vaccination Controversy Candice Brockwell 121 The Society’s Fortieth Anniversary Stuart Howard 137 People's Theatre: People's Education Keith Armstrong 144 2 north east history Recollections John Toft interview with John Creaby 153 Douglas Malloch interview with John Charlton 179 Educating René pt. -

Of St Cuthbert'

A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham by Ruth Robson of St Cuthbert' 1. Market Place Welcome to A Literary Pilgrimage of Durham, part of Durham Book Festival, produced by New Writing North, the regional writing development agency for the North of England. Durham Book Festival was established in the 1980s and is one of the country’s first literary festivals. The County and City of Durham have been much written about, being the birthplace, residence, and inspiration for many writers of both fact, fiction, and poetry. Before we delve into stories of scribes, poets, academia, prize-winning authors, political discourse, and folklore passed down through generations, we need to know why the city is here. Durham is a place steeped in history, with evidence of a pre-Roman settlement on the edge of the city at Maiden Castle. Its origins as we know it today start with the arrival of the community of St Cuthbert in the year 995 and the building of the white church at the top of the hill in the centre of the city. This Anglo-Saxon structure was a precursor to today’s cathedral, built by the Normans after the 1066 invasion. It houses both the shrine of St Cuthbert and the tomb of the Venerable Bede, and forms the Durham UNESCO World Heritage Site along with Durham Castle and other buildings, and their setting. The early civic history of Durham is tied to the role of its Bishops, known as the Prince Bishops. The Bishopric of Durham held unique powers in England, as this quote from the steward of Anthony Bek, Bishop of Durham from 1284-1311, illustrates: ‘There are two kings in England, namely the Lord King of England, wearing a crown in sign of his regality and the Lord Bishop of Durham wearing a mitre in place of a crown, in sign of his regality in the diocese of Durham.’ The area from the River Tees south of Durham to the River Tweed, which for the most part forms the border between England and Scotland, was semi-independent of England for centuries, ruled in part by the Bishop of Durham and in part by the Earl of Northumberland. -

Creative Media Production Enrichment - Js

CREATIVE MEDIA PRODUCTION ENRICHMENT - JS Creative question: What makes the North East Unique The focus of the project is to use a creative enquiry approach based around an open question. This will generate an agreed outcome that is entirely student led which will use different forms of media to showcase their findings. Teaching and Learning Role As teaching and Learning Lead, my role will be to advise and support on the programme development, act as a critical friend to challenge thinking and practice, analyse pedagogy and effective practice. I will engage in initial ideas, and help pupils to develop and become confident in managing a social enterprise event. I will review the social enterprise work with staff, outside visitors, pupils and parents. Date Activity Outcome Week 1 Key Question What makes the North Students take on the role of investigators and East Unique? brainstorm answers PPT mystery where is the Landmark? They solve clues to look at Landmarks in the What do we want to get out of a North East. project? They share their knowledge and come up What are our strengths? with a plan. Drama games/warm up activities What do we know about the North East? How Discussion of what an enquiry is, can we find out more? What is important to children to come up with the ideas people in the North East? How can we find after looking at information. They ask out? questions to extend their knowledge. They generate their own ideas and explore all the possibilities Week 2 Investigate and sketch features of the Students (with input from the teacher) decide North East which landmarks are a priority to visit. -

Museums, Health & Social Care Service

Museums, Health & Social Care service Contents 3 Introduction to Museums, Health & Social Care Service Resource Forewords by Professor Helen Chatterjee MBE, University College London 4 and Dr Neil Churchill OBE, NHS England 5 Roman herb garden 7 Bridges over the Tyne 9 Cosmetics through the ages - Brown sugar and honey lip scrub 11 Cosmetics through the ages - Epsom bath salts 13 North East cinema history 15 Art appreciation 17 Food in Georgian times – Tea 19 Food in Georgian times – Chocolate tasting 21 Non-walking walking tour 23 Food in Tudor times 25 Food rationing 27 Pigments and minerals 29 Colour and mood 31 Talking about objects and telling stories 33 Played in Tyne & Wear –The Blaydon races 35 Sketchy walks 37 Museum trails Through developing a strong partnership As well as supporting the existing professionals, Welcome to the between Tyne & Wear Archive & Museums and we are also working with the up and coming Northumbria University at Newcastle, Faculty of workforce as the resource will be used as part Museums, Health Health and Life Sciences, we created the steering of nurse education at Northumbria University. group whose role was to oversee this project. The group was made up of a multi-disciplinary We see these resources as a living collection of & Social Care team of health and social care practitioners useful ideas that will be added to and adapted, so and academics (occupational therapists, keep in touch by looking on the TWAM website Service resource. physiotherapists, mental health nurses, social and signing up to our mail out for news about new worker, and older people’s nurses). -

Washington Heritage Offer - Discussion Paper

REPORT FOR WASHINGTON AREA COMMITTEE 7 JANUARY 2010 REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR CITY SERVICES WASHINGTON HERITAGE OFFER - DISCUSSION PAPER 1.0 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1.1 The purpose of the report is for Members of the Washington Area Committee to discuss and recommend ways forward in relation to the Heritage agenda within Washington, in order that projects can be investigated and developed for the future. 2.0 BACKGROUND 2.1 Washington is located in the west of Sunderland and is divided into small villages or districts, with the original settlement being named Washington Village. Washington became a new town in 1964 and a part of Sunderland in 1974. Washington is now a diverse town offering wonderful countryside views, fascinating history, heritage and leisure attractions. 3.0 CONTEXT 3.1 Heritage is an area of continuing growth both across the region and for the City of Sunderland. Sunderland has a distinct heritage and there is a strong sense of pride across the city. This pride is based on our character and our traditions, including the distinct identity of specific communities and the cultural traditions of our people. A successful nomination which is currently being developed for World Heritage Status would allow the city to become a cultural heritage landmark as one of three World Heritage Sites across the region and 27 sites across the UK, allowing the city to prosper in areas such as economic development and tourism. 3.2 Heritage for the city is managed and delivered through the City Services Directorate, with two part-time heritage officers working to deliver the Heritage agenda. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS Victor Suthren (ed.). Canadian Stories of the episodes are located on waters contiguous Sea. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1993. with Canadian soil, but all are directly related ix + 278 pp. $17.95, paper; 0-19-540849-7. to the national life. A good example is Joshua Slocum's lone trip around the world. The Indelibly etched in my memory is my first segment the reader is treated to finds the reading assignment in History 101. It was a Nova Scotian sailor in the South Atlantic, book on the major rivers of Europe. Such while John Voss, another intrepid Canadian knowledge, the professor claimed, was essen• small boat voyager, is to be found battling tial to the study of European History. This mountainous seas in the South Pacific. book edited by Victor Suthren might not, The trilogy of World War II accounts at perhaps, be essential, but it would certainly be sea by such distinguished chroniclers as Hal beneficial for students of Canada. Unlike Lawrence, James B. Lamb and Joseph Schull much assigned reading, this collection is a provide poignant portraits of the pain and sheer delight to read, capturing, as it does, not agony of a generation of young Canadians in• only a lot of Canadian history but much of its decently rushed into becoming seasoned sea• culture as well. In all of this Canada's rivers, farers and in the course writing an important lakes and ocean waters play a major role. chapter in the nation's history. Stories about Suthren has gathered together thirty-two the Bluenose and the Marco Polo, with the stories in eight distinctive groupings: The tyrannical "Bully Forbes," will be familiar to First Peoples; The Newcomers; Blood On The many. -

Fatfield Circular Drummond

Key points of interest E) Arts Centre Washington Heritage Trails Washington Area The Arts Centre is a converted 19th A) Fatfield Bridge century farm, a ruin rescued at the time Designed by D. Balfour of Houghton- of the development of the new town in le-Spring, this bridge was built in 1889 1972. Originally called Biddick Farm at a cost of £8000. It was officially Arts Centre, it has gone through opened on 29 January 1890 by the several incarnations to become a 3rd Earl of Durham. vibrant multi-arts centre with a theatre, 6 B) Girdle Cake Cottage gallery, rehearsal rooms, artists studios, Walk The Biddick Pumping Station stands recording studio, café and award on the site of Girdle Cake Cottage. This winning bar. It is now owned and quaintly named dwelling was reputedly managed by Sunderland City Council. the refuge of the Earl of Perth, James F) Worm Hill Fatfield Circular Drummond. The Earl is said to have According to local legend this is the hill taken sanctuary here after the Jacobite which the Lambton Worm wrapped Walk Distance & Time: Army was defeated by the Duke of itself around after roaming the 2.9 miles or 4.8km Cumberland’s Government forces at surrounding countryside, terrorising the the Battle of Culloden in 1746. locals and devouring the cows and 1 hour (approx) C) Victoria Viaduct sheep. The summit offers fine views of This bridge is one of the most the semi-natural ancient woodlands of Start and Finish Point: impressive stone viaducts in Britain. the Wear corridor, with Penshaw Named after Queen Victoria, the final Monument above. -

North East History

Jubilee North East Edition History North North East History Volume 48 East • Fifty Years of the North East Labour History Society History • Picketing, Photography and Memory: Easington 1984-85 North East History Volume 48 2017 • Jack Trevena: WEA District Secretary and Conscientious Objector • The Bagnalls of Ouseburn: Watermen, Publican, and a Sporting Hero • Trade Unionism and Methodism • Rose Lumsden, a Sunderland Nurse in the Great War • Gender and Social Transformation in the 1970s 48 2017 Community Development Projects • Commemorative Plaques and Monuments – some recent examples • Davey Hopper 1943 – 2016. A Personal Appreciation The north east labour history society holds regular meetings on a wide variety of subjects. The society welcomes new members. We have an increasingly busy web-site at www.nelh.net Supporters are welcome to contribute to discussions Journal of the North East Labour History Society Volume 48 http://nelh.net/ 2017 Journal of the North East Labour History Society north east history North East Volume 48 2017 History ISSN 14743248 © 2017 NORTHUMBERLAND Printed by Azure Printing Units 1 F & G Pegswood Industrial Estate Pegswood Morpeth TYNE & Northumberland WEAR NE61 6HZ Tel: 01670 510271 DURHAM TEESSIDE Journal of the North East Labour History Society Copyright reserved on behalf of the authors and the North East Labour History Society © 2017 www.nelh.net 1 north east history Contents Note from the Editors 5 How to submit articles 8 Notes on contributors 9 Articles: Fifty Years of the North East Labour History Society 13 Picketing, Photography and Memory: Leanne Carr 31 Easington 1984-85 Another Kind of Heroism: Jack Trevena, Kath Connolly 43 Workers’ Educational Association North and Jude Murphy East District Secretary 1914-1919 and Conscientious Objector Conscientious Objectors 1916-1956 Sue King 59 Oral History interviews with a Daughter and Widows in Newcastle The Bagnalls of Ouseburn: Watermen, Mike Greatbatch 65 Publican, and a Sporting Hero Easington Colliery: My Pathway To Politics Harry Barnes 81 Trade Unionism and Methodism. -

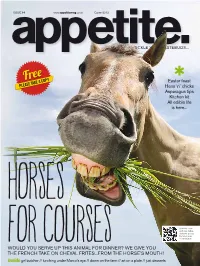

Horses for Courses Scan This Code

ISSUE 14 www.appetitemag.co.uk Easter 2013 T ICKLE YOUR TASTEBUDS... Easter feast Hens ‘n’ chicks Asparagus tips Kitchen kit All edible life is here... Horses Scan this code with your mobile device to access the latest news for courses on our website WOO ULD Y U seRVE UP THIS ANIMAL FOR DINNER? WE GIVE YOU THE FRENCH TAKE ON CHEVAL FRITES...FROM THE HORSE’S MOUTH! inside girl butcher // lunching under Marco’s eye // down on the farm // art on a plate // just desserts Appetite Advert_Layout 1 08/03/2013 15:32 Page 1 PLACE YOUR Editor, fazed by the fuss over ORDER FREE STAY horsemeat, ponders the wisdom 4 CLUB Great places, great offers of what we eat. If horse, why 6 FEED...BACK FRIDAYS not dog, after all? Reader recipes and news 7 it’s a dATE AT THE NEW Fab places to tour and taste There I was, minding my own business, trying to source a supplier so that he can NORTHUMBRIA HOTEL languishing of a Sunday morning on the serve cheval steak frites. Our other new 8 GIRL ABOUT TOON sofa under something called a Slanket columnist, butcher Charlotte Harbottle, Our lady Laura’s adventures in food (a blanket with foot and hand pockets; along with farmers and farm shop strange, but a greatly efficacious hangover proprietors, tells us that the scandal has at 10 LUNCH cure) when a rant began. “Horse! Horse! least made us all more conscious of the A feast at The Lambton Worm Dine at Louis' Jesmond on any Friday evening for two people & if you spend It’s like eating your dog. -

Buses Are Running to Emergency Timetables with Extra Journeys for Key Workers

April 2020 coronavirus (covid-19) buses are running to emergency timetables with extra journeys for key workers full timetables inside for more information see gonortheast.co.uk/coronavirus Go North East Whitley Bay - Metrocentre Coaster 1A via Marden, Tynemouth, North Shields, Howdon, Wallsend, Byker, Newcastle, Gateshead, Lobley Hill Daily Ref.No.: GNE08 Commencing Date: 18/04/2020 Service No 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH ABH Whitley Bay Bournemouth Gardens . ---- ---- ---- 0759 0859 0959 1059 1159 1259 1359 1459 1559 1659 1759 1859 2059 Whitley Bay Oxford Street . ---- ---- ---- 0803 0903 1003 1103 1203 1303 1403 1503 1603 1703 1803 1903 2103 Cullercoats John Street . ---- ---- ---- 0806 0906 1006 1106 1206 1306 1406 1506 1606 1706 1806 1906 2106 Marden Estate Lorton Avenue . ---- ---- ---- 0810 0910 1010 1110 1210 1310 1410 1510 1610 1710 1810 1910 2110 Tynemouth Park Hotel / Sea Life Centre . ---- ---- ---- 0814 0914 1014 1114 1214 1314 1414 1514 1614 1714 1814 1914 2114 Tynemouth Front Street . ---- ---- ---- 0816 0916 1016 1116 1216 1316 1416 1516 1616 1716 1816 1916 2116 North Shields Northumberland Square . ---- 0625 0721 0821 0921 1021 1121 1221 1321 1421 1521 1621 1721 1821 1921 2121 North Shields West Percy Street . Arr ---- 0626 0722 0822 0922 1022 1122 1222 1322 1422 1522 1622 1722 1822 1922 2122 North Shields West Percy Street . Dep 0515 0627 0723 0824 0924 1024 1124 1224 1324 1424 1524 1624 1724 1824 1924 2124 Percy Main The Redburn . .Arr 0521 0635 0731 0831 0931 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 1531 1631 1731 1832 1932 2132 Percy Main The Redburn . -

Alang the Road: Heritage Trail

Alang the Road A Heritage Trail Following the route of the Geordie anthem Blaydon Races. George Ridley “I took the bus” Balmbras Music Hall Mosley Street & St Nicholas’ Church George Ridley was born Blaydon Races tells the Going to the music hall In 1862 St Nicholas’ Church was not in Gateshead in 1835 into story of a bus journey in was the most popular yet a cathedral. Dating from the 12th a mining family. His first 1862 on a rainy summer leisure activity in the century or earlier, it was one of four job at the age of eight was afternoon. A group of 1860s. There were churches in Newcastle along with St as a trapper boy down people travelled from several music halls in John’s, St Andrew’s and All Saints. It a pit – a horrible job that Newcastle to watch the Newcastle, but Balmbras became a cathedral in 1882. meant sitting in the dark annual races in Blaydon. in the Cloth Market was Mosley Street was the first street in for hours on end, opening The vehicle they went the most famous. It was the world to be lit by electricity. Joseph and shutting doors. After in was an open-topped originally called the Wheat Swan, inventor of the light bulb (made being seriously injured at horse-drawn coach, Sheaf Inn, and was also in Benwell), had his shop here on the work in his twenties, he and the poor condition known as the Royal Music west side of the street. This building, embarked on a successful of the roads would Saloon.