Valérie Éliane Savard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Coldplay? 2016 CILL Season Begins 2016 Primary Election Results: So Goes City Island

Periodicals Paid at Bronx, N.Y. USPS 114-590 Volume 45 Number 4 May 2016 One Dollar Coldplay? 2016 CILL Season Begins By VIRGINIA DANNEGGER and KAREN NANI ria Piri, concession stand managers Jim and singlehandedly did the job of several and Sue Goonan, and equipment manager people. Even though his boys aged out of Lou Lomanaco. Several of these board the league, John still dedicates his time to members have served multiple terms on the help.” He presented John with a framed board. CILL jersey and a plaque in appreciation Mr. Esposito gave special thanks to for his support of the league and the City Photos by RICK DeWITT the outgoing president, John Tomsen, Island community. It was a chilly start to the 2016 Little League season on April 9, but the baseball tradi- who threw out the first pitch. “John has “As many of you know, volunteering tion dating back to 1900 is alive and warm on City Island. There are major, minor and time is a family commitment. Whether it t-ball teams competing once again this season. The ceremonial first pitch was thrown been president of the CILL since 2009 by outgoing president John Tomsen, who was also awarded a framed jersey by the Continued on page 19 new league president, Dom Esposito (right, top photo). New York State Assemblyman Michael Benedetto joined Catherine Ambrosini, Mr. Esposito and Mr. Tomsen (second photo, l. to r.) for the season opener. The American Legion color guard bearers led the teams in the “Star Spangled Banner.” As the weather warms up, head down to Ambro- 2016 Primary Election Results: sini Field next to P.S. -

6182 Rhodes & Singer.Indd

Consuming Images 6182_Rhodes & Singer.indd i 18/12/19 3:04 PM Robert Abel’s Bubbles (1974) 6182_Rhodes & Singer.indd ii 18/12/19 3:04 PM Consuming Images Film Art and the American Television Commercial Gary D. Rhodes and Robert Singer 6182_Rhodes & Singer.indd iii 18/12/19 3:04 PM Dedicated to Barry Salt and Gerald “Jerry” Schnitzer Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Gary D. Rhodes and Robert Singer, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun—Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 6068 2 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 6070 5 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 6071 2 (epub) The right of Gary D. Rhodes and Robert Singer to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 6182_Rhodes & Singer.indd iv 18/12/19 3:04 PM Contents List of Figures vi Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1. Origins 16 2. Narrative 36 3. Mise-en-scène 62 4. -

A Journal for Critical Debate Vol. 27 (2018)

Connotations A Journal for Critical Debate Volume 27 (2018) Connotations Society Connotations: A Journal for Critical Debate Published by Connotations: Society for Critical Debate EDITORS Inge Leimberg (Münster), Matthias Bauer (Tübingen), Burkhard Niederhoff (Bochum) and Angelika Zirker (Tübingen) Secretary: Eva Maria Rettner Editorial Assistants: Mirjam Haas, Tobias Kunz, Alia Luley, Sara Rogalski EDITORIAL ADDRESS Professor Matthias Bauer, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Department of English, Wilhelmstr. 50, 72074 Tübingen, Germany Email: [email protected] http://www.connotations.de EDITORIAL BOARD Judith Anderson, Indiana University Bloomington Åke Bergvall, University of Karlstad Christiane Maria Binder, Universität Dortmund Paul Budra, Simon Fraser University Lothar Černý, Fachhochschule Köln Eleanor Cook, University of Toronto William E. Engel, The University of the South Bernd Engler, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen David Fishelov, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem John P. Hermann, University of Alabama Lothar Hönnighausen, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Arthur F. Kinney, University of Massachusetts, Amherst Frances M. Malpezzi, Arkansas State University J. Hillis Miller, University of California, Irvine Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, Fordham University Martin Procházka, Charles University, Prague Alan Rudrum, Simon Fraser University Michael Steppat, Universität Bayreuth Leona Toker, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem John Whalen-Bridge, National University of Singapore Joseph Wiesenfarth, University of Wisconsin-Madison Connotations is a peer-reviewed journal that encourages scholarly communication in the field of English Literature (from the Middle English period to the present), as well as American and other Literatures in English. It focuses on the semantic and stylistic energy of the language of literature in a historical perspective and aims to represent different approaches. Connotations publishes articles and responses to articles, as well as to recent books. -

2018 – Volume 6, Number

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 & 3 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor KEVIN CALCAMP Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Bump in the Night” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of Pixabay/Kellepics EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH PAUL BOOTH Minnesota State University, Moorhead DePaul University GARY BURNS ANNE M. CANAVAN Northern Illinois University Salt Lake Community College BRIAN COGAN ASHLEY M. DONNELLY Molloy College Ball State University LEIGH H. EDWARDS KATIE FREDICKS Florida State University Rutgers University ART HERBIG ANDREW F. HERRMANN Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO KATHLEEN A. KENNEDY Maryville University of St. Louis Missouri State University SARAH MCFARLAND TAYLOR KIT MEDJESKY Northwestern University University of Findlay CARLOS D. MORRISON SALVADOR MURGUIA Alabama State University Akita International -

The Release: a Thesis

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-16-2014 The Release: A Thesis Jonathan Frey [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frey, Jonathan, "The Release: A Thesis" (2014). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1798. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1798 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Release A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Film Production By Jonathan Frey B.A. Tulane University, 2003 May 2014 © 2014, Jonathan Frey ii Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... -

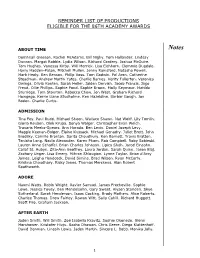

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

University of Groningen Narrative Metalepsis As Diegetic Concept In

University of Groningen Narrative Metalepsis as Diegetic Concept in Christopher Nolan’s 'Inception' (2010) Kiss, M. Published in: Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2012 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Kiss, M. (2012). Narrative Metalepsis as Diegetic Concept in Christopher Nolan’s 'Inception' (2010). Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies, 5, 35 - 54. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 26-09-2021 ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 5 (2012) 35–54 Narrative Metalepsis as Diegetic Concept in Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010) Miklós Kiss University of Groningen (the Netherlands) Email: [email protected] Abstract. The paper aims to revitalise Gérard Genette’s literary term of ‘metalepsis’ within a cinematic context,1 emphasising the expression’s creative potentials for both analytical and creative approaches. -

Volume 8, Number 1

POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State -

Virginia Minnesota Synopsis (Short) Childhood Friends Addison and Lyle Reunite 15 Years After a Tragedy That Robbed Them of Th

Virginia Minnesota Synopsis (Short) Childhood friends Addison and Lyle reunite 15 years after a tragedy that robbed them of their mysterious and inspirational little friend Virginia. The three girls had lived at Larsmont Bluff, a forbidding lakeside mansion, which served as a private home for children from troubled families. After the tragedy, the home was forced to close, and Addison and Lyle were sent off to unsettled futures many miles apart. Years later, when the owner dies, they are summoned back to Larsmont for the reading of the will. Together again, Addison and Lyle reluctantly return to a place they vowed never to return. They embark on an illuminating overnight journey where they revisit painful memories and discover long-forgotten gifts Virginia had bestowed on them so many years before. Synopsis (Long) Separated for fifteen years by a childhood tragedy that has haunted them ever since, two young women—Lyle and Addison—are reunited at the place both vowed never to return. Lyle and her unusual companion, a “wandering robot” named Mister that she’s picked up on the latest of her never-ending road trips across country, returns to Minnesota’s Lake Superior coastline for the first time since the devastating incident that robbed her and Addison of their mysterious and inspirational little friend named Virginia. Addison had fewer options than Lyle when the tragedy ended their time together at Larsmont Bluff – a private home for girls from troubled families. Lyle was shipped off to California to live with distant relatives, and instead of returning to her dysfunctional mother, Addison was sent to foster care until she aged out of the program and eventually succumbed to a life of dead-end jobs and small-town pettiness. -

Donor Bulletin 2 Caught in a Blessed Circle

2019 Donor Bulletin 2 Caught in a Blessed Circle Dear Friends, I recently met with a long-time seminary supporter. As we visited together, enjoying steaming cups of coffee on a frigid January morning, I asked him this question: “What inspires you to be so very generous? Why are you so generous?” “No one has ever asked me that before,” he responded. He sat back, and remained quiet for a few moments - then, he leaned toward me, fixing his gaze intently on mine, his elbows on his knees. The words were slow and deliberate. “Because I’m thankful to God. I’m grateful.” Gratitude inspires generosity, and generosity, in turn, inspires gratitude. It’s a blessed circle. We are grateful for your generosity, and inspired, too. Thank you so much for your continued support, patience, and prayers: all of the ways that you increase hope in and throughout the United Lutheran Seminary community. Your partnership, faith, and love in the shared ministry of theological education provides for the future of the Church. Over the past calendar year, we have had many blessings and opportunities arise for the seminary: • Our student body has increased to over 300 students; • We have been able to bring on a new Biblical Studies professor, Dr. Crystal Hall; • Different learning formats allow our students to learn in a variety of ways through distributed learning, online classes, and hybrid classrooms; • We have expanded continuing education opportunities for our lay and rostered leaders; • We continue to provide a thorough and comprehensive education, giving graduates the tools necessary to lead in a variety of ways; • The Urban Theological Institute now has 27 degree students and 43 certificate students; • Student borrowing has decreased to 23%: less than a quarter of our students take out loans! • A bequest of $30 million given toward student scholarships and one faculty chair will ensure that our support of students can continue and grow. -

Zombies, Reavers, Butchers, and Actuals in Joss Whedon's Work Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2012 Zombies, Reavers, Butchers, and Actuals in Joss Whedon's Work Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Zombies, Reavers, Butchers, and Actuals in Joss Whedon's Work," in Joss Whedon: The Complete Companion: The TV Series, The Movies, The Comic Books and More. Ed. PopMatters Media. London: Titan Books, 2012: 285-297. Publisher Link. © 2012 Titan Books. Used with permission. FIREFLY 3.10 3.10 Zombies, Reavers, Butchers, and Actuals in Joss Whedon's Work Gerry Canavan For all the standard horror movie monsters Joss Whedon took up in Buffy and Angel-vampires, of course, but also ghosts, demons, werewolves, witches, Frankenstein's monster, the Devil, mummies, haunted puppets, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, the "bad boyfriend," and so on-you'd think there would have been more zombies. In twelve years of television across both series zombies appear in only a handful of episodes. They attack almost as an afterthought at Buffy's drama-laden homecoming party early in Buffy Season 3 ("Dead Man's Party" 3.2); they completely ruin Xander's evening in "The Zeppo" (3.13) later that same season; they patrol Angel's Los Angeles neighborhood in "The Thin Dead Line" (2.14) in Angel Season 2; they stalk the halls of Wolfram & Hart in "Habeas Corpses" (4.8) in Angel Season 4. A single zombie comes back from the dead to work things out with the girlfriend who poisoned him in a subplot in "Provider" (3.12) in Angel Season 3; Adam uses science to reanimate dead bodies to make his lab assistants near the end of Buffy Season 4 ("Primeval" 4.21); zombies guard a fail-safe device in the basement of Wolfram & Hart in "You're Welcome" (3.12) in Angel Season 5.