Research Article QUANTITATIVE and DYNAMIC EXPRESSION PROFILE of PREMATURE and ACTIVE FORMS of the REGIONAL ADAM PROTEINS DURING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human ADAM12 Quantikine ELISA

Quantikine® ELISA Human ADAM12 Immunoassay Catalog Number DAD120 For the quantitative determination of A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase domain- containing protein 12 (ADAM12) concentrations in cell culture supernates, serum, plasma, and urine. This package insert must be read in its entirety before using this product. For research use only. Not for use in diagnostic procedures. TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................................................1 PRINCIPLE OF THE ASSAY ...................................................................................................................................................2 LIMITATIONS OF THE PROCEDURE .................................................................................................................................2 TECHNICAL HINTS .................................................................................................................................................................2 MATERIALS PROVIDED & STORAGE CONDITIONS ...................................................................................................3 OTHER SUPPLIES REQUIRED .............................................................................................................................................3 PRECAUTIONS .........................................................................................................................................................................4 -

ADAM9: a Novel Player in Vestibular Schwannoma Pathogenesis

1856 ONCOLOGY LETTERS 19: 1856-1864, 2020 ADAM9: A novel player in vestibular schwannoma pathogenesis MARIA BREUN1, ALEXANDRA SCHWERDTFEGER1, DONATO DANIEL MARTELLOTTA1, ALMUTH F. KESSLER1, CAMELIA M. MONORANU2, CORDULA MATTHIES1, MARIO LÖHR1* and CARSTEN HAGEMANN1* 1Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Würzburg; 2Department of Neuropathology, Institute of Pathology, University of Würzburg, D-97080 Würzburg, Germany Received April 27, 2019; Accepted October 2, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2020.11299 Abstract. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 9 (ADAM9) is VS samples (n=60). A total of 30 of them were from patients a member of the transmembrane ADAM family. It is expressed with neurofibromatosis. Healthy peripheral nerves from in different types of solid cancer and promotes tumor invasive- autopsies (n=10) served as controls. ADAM9 mRNA levels ness. To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the were measured by PCR, and protein levels were determined first to examine ADAM9 expression in vestibular schwan- by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and western blotting (WB). nomas (VS) from patients with and without neurofibromatosis The Hannover Classification was used to categorize tumor type 2 (NF2) and to associate the data with clinical parameters extension and hearing loss. ADAM9 mRNA levels were of the patients. The aim of the present study was to evaluate 8.8-fold higher in VS compared with in controls. The levels if ADAM9 could be used as prognostic marker or therapeutic were 5.6-fold higher in patients with NF2 and 12-fold higher in target. ADAM9 mRNA and protein levels were measured in patients with sporadic VS. WB revealed two mature isoforms of the protein, and according to IHC ADAM9 was mainly expressed by S100-positive Schwann cells. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Importance of Β-APP, ADAM9, 10, 17 in Alzheimer Disease

Available online at www.ijmrhs.com al R edic ese M a of rc l h a & n r H u e o a J l l t h International Journal of Medical Research & a n S ISSN No: 2319-5886 o c i t i Health Sciences, 2019, 8(7): 68-7 e a n n c r e e t s n I • • I J M R H S Importance of β-APP, ADAM9, 10, 17 in Alzheimer Disease: Preliminary Autopsy Study with Immunohistochemical Expression in Human Brain Filiz Eren1, Nursel Turkmen Inanır1,2, Recep Fedakar2, Bulent Eren3*, Murat Serdar Gurses1, Mustafa Numan Ural4, Sumeyya Akyol5, Busra Aynekin5 and Kadir Demircan5 1 Bursa Morgue Department, Council of Forensic Medicine of Turkey, Bursa, Turkey 2 Department of Forensic Medicine, School of Medicine, Uludag University, Bursa, Turkey 5 3 Department of Forensic Medicine, School of Medicine, Tokat Gaziosmanpaşa University Tokat, Turkey 4 5 Bilgemed Work Safety and Security, Bursa, Turkey 5 Independent Researcher, Ankara, Turkey *Corresponding e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is encountered as an important health problem. It was exposed that in the pathophysiology of AD, formation, and aggregation of amyloid β from amyloid precursor protein ( APP), was restrained by α-secretase group, ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase) enzymes. From this perspective, ADAM group of enzymes can be presumably used in the future both as a diagnostic marker, and potential treatment modality. In our study, 9 cases with or without AD in different age groups with various causes of death who were autopsied in the Bursa Morgue Department of the Council of Forensic Medicine of Turkey were included in the study. -

The Positive Side of Proteolysis in Alzheimer's Disease

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Biochemistry Research International Volume 2011, Article ID 721463, 13 pages doi:10.1155/2011/721463 Review Article Zinc Metalloproteinases and Amyloid Beta-Peptide Metabolism: The Positive Side of Proteolysis in Alzheimer’s Disease Mallory Gough, Catherine Parr-Sturgess, and Edward Parkin Division of Biomedical and Life Sciences, School of Health and Medicine, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Edward Parkin, [email protected] Received 17 August 2010; Accepted 7 September 2010 Academic Editor: Simon J. Morley Copyright © 2011 Mallory Gough et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by an accumulation of toxic amyloid beta- (Aβ-)peptides in the brain causing progressive neuronal death. Aβ-peptides are produced by aspartyl proteinase-mediated cleavage of the larger amyloid precursor protein (APP). In contrast to this detrimental “amyloidogenic” form of proteolysis, a range of zinc metalloproteinases can process APP via an alternative “nonamyloidogenic” pathway in which the protein is cleaved within its Aβ region thereby precluding the formation of intact Aβ-peptides. In addition, other members of the zinc metalloproteinase family can degrade preformed Aβ-peptides. As such, the zinc metalloproteinases, collectively, are key to downregulating Aβ generation and enhancing its degradation. It is the role of zinc metalloproteinases in this “positive side of proteolysis in Alzheimer’s disease” that is discussed in the current paper. 1. Introduction of 38–43 amino acid peptides called amyloid beta (Aβ)- peptides. -

Selective Inhibition of ADAM12 Catalytic Activity Through

Selective inhibition of ADAM12 catalytic activity through engineering of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-2 Marie Kveiborg, Jonas Jacobsen, Meng-Huee Lee, Hideaki Nagase, Ulla M Wewer, Gillian Murphy To cite this version: Marie Kveiborg, Jonas Jacobsen, Meng-Huee Lee, Hideaki Nagase, Ulla M Wewer, et al.. Selective inhibition of ADAM12 catalytic activity through engineering of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-2. Biochemical Journal, Portland Press, 2010, 430 (1), pp.79-86. 10.1042/BJ20100649. hal-00506526 HAL Id: hal-00506526 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00506526 Submitted on 28 Jul 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Biochemical Journal Immediate Publication. Published on 10 Jun 2010 as manuscript BJ20100649 Selective inhibition of ADAM12 catalytic activity through engineering of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-2 Marie Kveiborg*,§, Jonas Jacobsen*,§, Meng-Huee Lee†, Hideaki Nagase‡, Ulla M. Wewer*,¶, and Gillian Murphy†,¶ *Department of Biomedical Sciences and Biotech Research and Innovation Centre (BRIC), University of Copenhagen, Ole Maaløes Vej 5, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark †Department of Oncology, Cambridge University, Cancer Research Institute, Li Ka Shing Centre, Cambridge CB2 ORE, UK ‡Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology Division, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, 65 Aspenlea Road, London W6 8LH, UK §,¶These authors contributed equally to the study. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Differential Gene Expression and Functional Analysis Implicate Novel Mechanisms in Enteric Nervous System Precursor Migration and Neuritogenesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Developmental Biology 298 (2006) 259–271 www.elsevier.com/locate/ydbio Differential gene expression and functional analysis implicate novel mechanisms in enteric nervous system precursor migration and neuritogenesis Bhupinder P.S. Vohra a, Keiji Tsuji b,c, Mayumi Nagashimada b,d, Toshihiro Uesaka b, ⁎ ⁎ Daniel Wind a, Ming Fu a, Jennifer Armon a, Hideki Enomoto b, , Robert O. Heuckeroth a, a Department of Pediatrics and Department of Molecular Biology and Pharmacology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Avenue, Box 8208, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA b Laboratory for Neuronal Differentiation and Regeneration, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, 2-2-3 Minatojima-minamimachi, Chuo-ku, Kobe, Hyogo 650-0047, Japan c Department of Pediatrics, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Graduate School of Medical Science, Kamigyo-ku, Kyoto 602-8566, Japan d Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-2 Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan Received for publication 17 April 2006; revised 17 May 2006; accepted 22 June 2006 Available online 27 June 2006 Abstract Enteric nervous system (ENS) development requires complex interactions between migrating neural-crest-derived cells and the intestinal microenvironment. Although some molecules influencing ENS development are known, many aspects remain poorly understood. To identify additional molecules critical for ENS development, we used DNA microarray, quantitative real-time PCR and in situ hybridization to compare gene expression in E14 and P0 aganglionic or wild type mouse intestine. Eighty-three genes were identified with at least two-fold higher expression in wild type than aganglionic bowel. -

Zinc Metalloproteinases and Amyloid Beta-Peptide Metabolism: the Positive Side of Proteolysis in Alzheimer’S Disease

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Biochemistry Research International Volume 2011, Article ID 721463, 13 pages doi:10.1155/2011/721463 Review Article Zinc Metalloproteinases and Amyloid Beta-Peptide Metabolism: The Positive Side of Proteolysis in Alzheimer’s Disease Mallory Gough, Catherine Parr-Sturgess, and Edward Parkin Division of Biomedical and Life Sciences, School of Health and Medicine, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YQ, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Edward Parkin, [email protected] Received 17 August 2010; Accepted 7 September 2010 Academic Editor: Simon J. Morley Copyright © 2011 Mallory Gough et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by an accumulation of toxic amyloid beta- (Aβ-)peptides in the brain causing progressive neuronal death. Aβ-peptides are produced by aspartyl proteinase-mediated cleavage of the larger amyloid precursor protein (APP). In contrast to this detrimental “amyloidogenic” form of proteolysis, a range of zinc metalloproteinases can process APP via an alternative “nonamyloidogenic” pathway in which the protein is cleaved within its Aβ region thereby precluding the formation of intact Aβ-peptides. In addition, other members of the zinc metalloproteinase family can degrade preformed Aβ-peptides. As such, the zinc metalloproteinases, collectively, are key to downregulating Aβ generation and enhancing its degradation. It is the role of zinc metalloproteinases in this “positive side of proteolysis in Alzheimer’s disease” that is discussed in the current paper. 1. Introduction of 38–43 amino acid peptides called amyloid beta (Aβ)- peptides. -

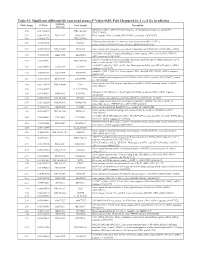

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Comparative Transcriptome Analyses Reveal Genes Associated with SARS-Cov-2 Infection of Human Lung Epithelial Cells

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.24.169268; this version posted June 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Comparative transcriptome analyses reveal genes associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection of human lung epithelial cells Darshan S. Chandrashekar1, *, Upender Manne1,2,#, Sooryanarayana Varambally1,2,3,#* 1Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 2Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 3Institute of Informatics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL # Share Senior Authorship (UM Email: [email protected]) *Correspondence to: Sooryanarayana Varambally, Ph.D., Molecular and Cellular Pathology, Department of Pathology, Wallace Tumor Institute, 4th floor, 20B, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35233, USA Phone: (205) 996-1654 Email: [email protected] And Darshan S. Chandrashekar Ph.D., Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL Email: [email protected] Running Title: SARS-CoV-2 gene signature in infected lung epithelial cells Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed. Page | 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.24.169268; this version posted June 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract: Understanding the molecular mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection (the cause of COVID-19) is a scientific priority for 2020. Various research groups are working toward development of vaccines and drugs, and many have published genomic and transcriptomic data related to this viral infection. -

Original Article Tetraspanin CD9 Interacts with Α-Secretase to Enhance Its Oncogenic Function in Pancreatic Cancer

Am J Transl Res 2020;12(9):5525-5537 www.ajtr.org /ISSN:1943-8141/AJTR0105976 Original Article Tetraspanin CD9 interacts with α-secretase to enhance its oncogenic function in pancreatic cancer Weiwei Lu1*, Aihua Fei1*, Ying Jiang2, Liang Chen1, Yunkun Wang2 1Department of Emergency, Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200092, PR China; 2Department of Neurosurgery, Shanghai Changzheng Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Second Military Medical University, 415 Feng Yang Rd, Shanghai 200003, PR China. *Equal contributors. Received December 5, 2019; Accepted June 6, 2020; Epub September 15, 2020; Published September 30, 2020 Abstract: Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal cancers and its prognosis remains poor. ADAM family proteins like ADAM10, ADAM9 and ADAM17 function as α-secretase to cleavage cell surface proteins like Notch to facilitate oncogenesis in various tumors. The oncogenic roles of α-secretase in PDAC have been demonstrated but it remains unknown that whether and how α-secretase is regulated in PDAC. Here, we report that the expression of tetraspanin CD9 was increased and strongly associated with poor prognosis in PDAC. CD9 expression was positively associated with α-secretase activity in PDAC tissues and CD9 knock-down inhibited α-secretase activity in PDAC cell lines. Co-immunoprecipitation and GST pull down demonstrates that CD9 directly interacted with ADAM10, ADAM9 and ADAM17, respectively. Cell surface biotin labeling and immunostaining of tagged ADAM proteins show that CD9 promoted cell surface trafficking of ADAM family proteins. In addition, the antibody targeting extracellular domain of CD9 disrupted the interactions between CD9 and ADAM family proteins, reduced cell surface trafficking of ADAM proteins and inhibited α-secretase activity.