Students' Views About the Nature of Experimental Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Original Way of Teaching Geometrical Optics C. Even

Learning through experimenting: an original way of teaching geometrical optics C. Even1, C. Balland2 and V. Guillet3 1 Laboratoire de Physique des Solides, CNRS, Université Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, F-91405 Orsay, France 2 Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Université Paris 6, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cite, CNRS-IN2P3, Laboratoire de Physique Nucléaire et des Hautes Energies (LPNHE), 4 place Jussieu, F-75252, Paris Cedex 5, France 3 Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Université Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, F- 91405 Orsay, France E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Over the past 10 years, we have developed at University Paris-Sud a first year course on geometrical optics centered on experimentation. In contrast with the traditional top-down learning structure usually applied at university, in which practical sessions are often a mere verification of the laws taught during preceding lectures, this course promotes “active learning” and focuses on experiments made by the students. Interaction among students and self questioning is strongly encouraged and practicing comes first, before any theoretical knowledge. Through a series of concrete examples, the present paper describes the philosophy underlying the teaching in this course. We demonstrate that not only geometrical optics can be taught through experiments, but also that it can serve as a useful introduction to experimental physics. Feedback over the last ten years shows that our approach succeeds in helping students to learn better and acquire motivation and autonomy. This approach can easily be applied to other fields of physics. Keywords : geometrical optics, experimental physics, active learning 1. Introduction Teaching geometrical optics to first year university students is somewhat challenging, as this field of physics often appears as one of the less appealing to students. -

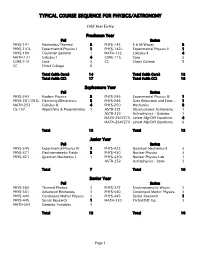

Typical Course Sequence for Physics/Astronomy

TYPICAL COURSE SEQUENCE FOR PHYSICS/ASTRONOMY Odd Year Entry Freshman Year Fall Spring PHYS-141 Mechanics/Thermal 3 PHYS-142 E & M/Waves 3 PHYS-141L Experimental Physics I 1 PHYS-142L Experimental Physics II 1 PHYS-190 Freshman Seminar 1 MATH-132 Calculus II 4 MATH-131 Calculus I 4 CORE-115 Core 5 CORE-110 Core 5 CC Christ College 8 CC Christ College 8 Total (with Core) 14 Total (with Core) 13 Total (with CC) 17 Total (with CC) 16 Sophomore Year Fall Spring PHYS-243 Modern Physics 3 PHYS-245 Experimental Physics III 1 PHYS-281/281L Electricity/Electronics 3 PHYS-246 Data Reduction and Error... 1 MATH-253 Calculus III 4 PHYS-250 Mechanics 3 CS-157 Algorithms & Programming 3 ASTR-221 Observational Astronomy 1 ASTR-253 Astrophysics - Galaxies 3 MATH-260/270 Linear Alg/Diff Equations 4 MATH-264/270 Linear Alg/Diff Equations 6 Total 13 Total 13 Junior Year Fall Spring PHYS-345 Experimental Physics IV 1 PHYS-422 Quantum Mechanics II 3 PHYS-371 Electromagnetic Fields 3 PHYS-430 Nuclear Physics 3 PHYS-421 Quantum Mechanics I 3 PHYS-430L Nuclear Physics Lab 1 ASTR-252 Astrophysics - Stars 3 Total 7 Total 10 Senior Year Fall Spring PHYS-360 Thermal Physics 3 PHYS-372 Electromagnetic Waves 3 PHYS-381 Advanced Mechanics 3 PHYS-440 Condensed Matter Physics 3 PHYS-440 Condensed Matter Physics 3 PHYS-445 Senior Research 1 PHYS-445 Senior Research 1 MATH-330 Partial Diff. Eq. 3 MATH-334 Complex Variables 3 Total 13 Total 10 Page 1 TYPICAL COURSE SEQUENCE FOR PHYSICS/ASTRONOMY Even Year Entry Freshman Year Fall Spring PHYS-141 Mechanics/Thermal 3 PHYS-142 E & M/Waves 3 PHYS-141L Experimental Physics I 1 PHYS-142L Experimental Physics II 1 PHYS-190 Freshman Seminar 1 MATH-132 Calculus II 4 MATH-131 Calculus I 4 CORE-115 Core 5 CORE-110 Core 5 CC Christ College 8 CC Christ College 8 Total (with Core) 14 Total (with Core) 13 Total (with CC) 17 Total (with CC) 16 Sophomore Year Fall Spring PHYS-243 Modern Physics 3 PHYS-245 Experimental Physics III 1 PHYS-281 Electricity/Electronics 3 PHYS-250 Mechanics 3 MATH-253 Calculus III 4 PHYS-246 Data Reduction and Error.. -

Physics, M.S. 1

Physics, M.S. 1 PHYSICS, M.S. DEPARTMENT OVERVIEW The Department of Physics has a strong tradition of graduate study and research in astrophysics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; condensed matter physics; high energy and particle physics; plasma physics; quantum computing; and string theory. There are many facilities for carrying out world-class research (https://www.physics.wisc.edu/ research/areas/). We have a large professional staff: 45 full-time faculty (https://www.physics.wisc.edu/people/staff/) members, affiliated faculty members holding joint appointments with other departments, scientists, senior scientists, and postdocs. There are over 175 graduate students in the department who come from many countries around the world. More complete information on the graduate program, the faculty, and research groups is available at the department website (http:// www.physics.wisc.edu). Research specialties include: THEORETICAL PHYSICS Astrophysics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; condensed matter physics; cosmology; elementary particle physics; nuclear physics; phenomenology; plasmas and fusion; quantum computing; statistical and thermal physics; string theory. EXPERIMENTAL PHYSICS Astrophysics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; biophysics; condensed matter physics; cosmology; elementary particle physics; neutrino physics; experimental studies of superconductors; medical physics; nuclear physics; plasma physics; quantum computing; spectroscopy. M.S. DEGREES The department offers the master science degree in physics, with two named options: Research and Quantum Computing. The M.S. Physics-Research option (http://guide.wisc.edu/graduate/physics/ physics-ms/physics-research-ms/) is non-admitting, meaning it is only available to students pursuing their Ph.D. The M.S. Physics-Quantum Computing option (http://guide.wisc.edu/graduate/physics/physics-ms/ physics-quantum-computing-ms/) (MSPQC Program) is a professional master's program in an accelerated format designed to be completed in one calendar year.. -

Experimental Physics I PHYS 3250/3251

Syllabus Experimental Physics I PHYS 3250/3251 Course Description: Introduction to experimental modern physics, measurement of fundamental constants, repetition of crucial experiments of modern physics (Stern Gerlach, Zeeman effect, photoelectric effect, etc.) Course Objectives: The objective of this course is introduce you to the proper methods for conducting controlled physics experiments, including the acquisition, analysis and physical interpretation of data. The course involves experiments which illustrate the principles of modern physics, e.g. the quantum nature of charge and energy, etc. Succinct, journal-style reports will be the primary output for each experiment, with at least one additional presentation (oral and/or poster) required. Text: An Introduction to Error Analysis, 2nd Edition, J.R. Taylor, ISBN 0-935702-75-X. Additional documentation for any assigned experiments will be supplied as needed. Learning Outcomes: At the conclusion of this course, students will be able to: 1) Assemble and document a relevant bibliography for a physics experiment. 2) Prepare a journal-style manuscript using scientific typesetting software. 3) Plan and conduct experimental measurements in physics while employing proper note-taking methods. 4) Calculate uncertainties for physical quantities derived from experimental measurements. Clemson Thinks2: What is Critical Thinking? This course is designed to be part of the Clemson Thinks2 (CT2) program. “Critical thinking is reasoned and reflective judgment applied to solving problems or making decisions about what to believe or what to do. Critical thinking gives reasoned consideration to defining and analyzing problems, identifying and evaluating options, inferring likely outcomes and probable consequences, and explaining the reasons, evidence, methods and standards used in making those analyses, inferences and evaluations. -

Modern Experimental Physics Introduction for Physics 401 Students

Modern Experimental Physics Introduction for Physics 401 students Spring 2014 Eugene V. Colla • Goals of the course • Experiments • Teamwork • Schedule and assignments • Your working mode Physics 401 Spring 2013 2 • Primary: Learn how to “do” research Each project is a mini-research effort How are experiments actually carried out Use of modern tools and modern analysis and data-recording techniques Learn how to document your work • Secondary: Learn some modern physics Many experiments were once Nobel-prize-worthy efforts They touch on important themes in the development of modern physics Some will provide the insight to understand advanced courses Some are just too new to be discussed in textbooks Physics 401 Spring 2013 3 Primary. Each project is a mini-research effort Step1. Preparing: • Sample preparation • Wiring the setup • Testing electronics Preparing the samples for ferroelectric measurements Courtesy of Emily Zarndt & Mike Skulski (F11) Standing waves resonances in Second Step2. Taking data: Sound experiment If problems – go back to Courtesy of Mae Hwee Teo and Step 1. Vernie Redmon (F11) Physics 401 Spring 2013 4 Primary. Each project is a mini-research effort Plot of coincidence rate for 22Na against the angle between detectors A and B. The fit is a Step3. Data Analysis Gaussian function centred at If data is “bad” or not 179.30° with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 14.75°. enough data point – go back to Step 2 Courtesy of Bi Ran and Thomas Woodroof Author#1 and Author#2 Step4. Writing report and preparing the talk Physics 401 Spring 2013 5 Primary. -

On the Shoulders of Giants: a Brief History of Physics in Göttingen

1 6 ON THE SHO UL DERS OF G I A NTS : A B RIEF HISTORY OF P HYSI C S IN G Ö TTIN G EN On the Shoulders of Giants: a brief History of Physics in Göttingen 18th and 19th centuries Georg Ch. Lichtenberg (1742-1799) may be considered the fore- under Emil Wiechert (1861-1928), where seismic methods for father of experimental physics in Göttingen. His lectures were the study of the Earth's interior were developed. An institute accompanied by many experiments with equipment which he for applied mathematics and mechanics under the joint direc- had bought privately. To the general public, he is better known torship of the mathematician Carl Runge (1856-1927) (Runge- for his thoughtful and witty aphorisms. Following Lichtenberg, Kutta method) and the pioneer of aerodynamics, or boundary the next physicist of world renown would be Wilhelm Weber layers, Ludwig Prandtl (1875-1953) complemented the range of (1804-1891), a student, coworker and colleague of the „prince institutions related to physics proper. In 1925, Prandtl became of mathematics“ C. F. Gauss, who not only excelled in electro- the director of a newly established Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute dynamics but fought for his constitutional rights against the for Fluid Dynamics. king of Hannover (1830). After his re-installment as a profes- A new and well-equipped physics building opened at the end sor in 1849, the two Göttingen physics chairs , W. Weber and B. of 1905. After the turn to the 20th century, Walter Kaufmann Listing, approximately corresponded to chairs of experimen- (1871-1947) did precision measurements on the velocity depen- tal and mathematical physics. -

Research in High Energy Physics

,*•'••' Annual Technical Progress Report and FY 1997 Budget Request for DOE Grant DE-FG03-94ER40833 to The U.S. Department of Energy San Francisco Operations Office from The University of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Title of Project: RESEARCH IN HIGH ENERGY PHYSICS December 1, 1993 to November 30, 1998 (FY94-FY98) Principal Investigators Stephen L. Olsen Xerxes Tata Experimental Physics Theoretical Physics G<: fun DOCUMENT IS UMJTO ASTER Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Overview 2 1.1.1 Background 3 1.1.2 Recent Accomplishments 4 1.1.3 Personnel Changes 5 2 Accelerator-Based Experiments 6 2.1 The BELLE Experiment 6 2.1.1 Physics Motivation 6 2.1.2 The BELLE Detector 7 2.1.3 Hawaii Participation in BELLE 10 2.1.4 BELLE Equipment Budget 18 2.1.5 Detector Integration 19 2.1.6 Budget 19 2.1.7 Publications 19 2.2 The BES Experiment 21 2.2.1 V' Physics 21 2.2.2 Xc Physics 31 2.2.3 Charm Physics: measurement of fz>a and fn 34 2.2.4 CODEMAN 35 2.2.5 The BES upgrade 35 2.2.6 Recent BES publications: 38 2.3 The CLEO-II Experiment 41 2.3.1 Studies of inclusive B Meson decays 41 2.3.2 Search for the process b —• s gluon 42 2.3.3 Exclusive hadronic B decays 45 ii DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document 2.3.4 Determination of CKM matrix elements 47 2.3.5 Bs - Bs Mixing 47 2.3.6 Doubly Cabibbo-suppressed D° meson decay and D° — D° mixing 48 2.3.7 CLEO II particle ID 49 2.3.8 Reviews of B Physics 51 2.4 The DO Experiment 53 2.4.1 Top Mass Fitting 53 2.4.2 Hawaii analyses to extract the top mass 56 2.4.3 Another pseudolikelihood fit 58 2.4.4 Optimal cuts 59 2.4.5 HT analysis 62 2.4.6 Personnel 64 2.4.7 Other Activities 64 2.4.8 Future Plans 64 2.4.9 Publications 64 2.5 The AMY Experiment . -

Experimental Physics Seminar PHYS 210, Spring 2006 Department of Physics Princeton University

Experimental Physics Seminar PHYS 210, Spring 2006 Department of Physics Princeton University Prof. Michael Romalis, Office: Jadwin 230, Phone 8-5586, e-mail: [email protected] TA: Georgios Vasilakis Office: Jadwin B21, Phone 8-0702, e-mail: [email protected] Technical: Dan Hoffman Office: Jadwin B19, Phone 8-5441, e-mail: [email protected] Web page: www.princeton.edu/~romalis/PHYS210 Class: Wednesday, 7:30 –10:20, Jadwin 475 and 469 Class structure In the first half of the semester we will go over modern experimental physics techniques in major areas of physics: high energy and nuclear physics, condensed matter physics, atomic physics, astrophysics, and biophysics. The emphasis will be on actual hands-on experimental aspects. The underlying physics, some of which may be new to you, will be covered in a “hand-waving” fashion to give you a taste of things discussed in more advanced physics classes. You will be expected to read lecture notes available on the web before the class. We will typically have a 30-min lecture followed by “show-and-tell” of the experimental apparatus. The first three labs will be particularly hands-on and will focus on LabView, a program commonly used for computer control of experiments, and simple electronic circuits. In the second half of the semester you will work on independent projects in groups of 2-4 people. A list of possible projects is given below. You are also welcome to propose your own project ideas. If you ever wanted to build a crazy contraption or demonstrate a counter-intuitive physical effect, now is your chance to do it with full support of Princeton Physics department! We are also looking for new ideas for Freshman lab experiments. -

High Energy Physics Subpanel Report

DOE/ER-0718 HEPAP Subpanel Report on PLANNING FOR THE FUTURE OF U.S. HIGH-ENERGY PHYSICS February 1998 T O EN FE TM N R E A R P G E Y D U • • A N C I I T R E D E M ST A ATES OF U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Research Division of High Energy Physics EXECUTIVE SUMMARY High-energy physicists seek to understand the universe by investigating the most basic particles and the forces between them. Experiments and theoretical insights over the past several decades have made it possible to see the deep connections between apparently unrelated phenomena and to piece together more of the story of how a rich and complex cosmos could evolve from just a few kinds of elementary particles. Our nations contributions to this remarkable achievement have been made possible by the federal governments support of basic research and the development of the state- of-the-art accelerators and detectors needed to investigate the physics of the elementary particles. This investment has been enormously successful: of the fifteen Nobel Prizes awarded for research in experimental and theoretical particle physics over the past forty years, physicists in the U.S. program won or shared in thirteen and account for twenty- four of the twenty-nine recipients. New high-energy physics facilities now under construction will allow us to take the next big steps toward understanding the origin of mass and the asymmetry between the behavior of matter and antimatter. The U.S. Department of Energy has asked its High Energy Physics Advisory Panel (HEPAP) to recommend a scenario for an optimal and balanced U.S. -

Physical Conclusions of Experimental Physics Versus Metaphysical

Physical Conclusions of Experimental Physics Versus Metaphysical Assumptions of Theoretical Physics Theoretical physicists create assumptions for their theories to explain the results of measurements made by experimental physicists. If the as- sumption corresponds to the measured values then it is a physical assump- tion and becomes a principle of measurement. If the initial assumption does not correspond to the experimental measurement it is a metaphysical assumption and becomes a theory of measurement. Experimental physi- cists validate principles for the measurement of mass, space, time, and gravity and theoretical physicists imagine unmeasured theories of atoms, photons, and the force and motion of gravity. An example of a principle of measurement is an accelerometer read- ing. The physical assumption is that force (F = ma) changes the direction and magnitude of the motion of mass along a single vector. The result of change in motion is a positive or negative value of momentum p = m+/-v. Change is measured as acceleration/deceleration (a/d = F/m). Measure- ments show that accelerometers measure an unknown combination of ac- celeration and deceleration along a single vector. The total quantity of a force is momentum and momentum is the basis of all measured physical interactions, Another principle of measurement is the clock reading. The physical assumption of the clock is the idea that a spinning rigid body of mass will continue to spin at a constant rate (rpm) until its conserved quantity of angular momentum is changed by a centrifugal acceleration/deceleration. The rate of a Cesium clock is a function of the angular momentum of the Cesium-133 atom. -

PHYS - Physics 1

PHYS - Physics 1 PHYS428 Physics Capstone Research (2-4 Credits) PHYS - PHYSICS Individual, focused research under the guidance of a faculty member. Discussion, presentations and, if appropriate, research group projects PHYS401 Quantum Physics I (4 Credits) involved. Student must submit final research paper for completion of Introduces some quantum phenomena leading to wave-particle duality. course. Paper may also serve as thesis required for High Honors in Schroedinger theory for bound states and scattering in one dimension. Physics. Not intended as a general "reading course" (see PHYS499). One-particle Schroedinger equation and the hydrogen atom. Restriction: Must be in a major within CMNS-Physics department; and Prerequisite: PHYS371 and PHYS373. senior standing or higher; and permission of instructor. Formerly: PHYS421. Repeatable to: 4 credits. PHYS402 Quantum Physics II (4 Credits) PHYS429 Atomic and Nuclear Physics Laboratory (3 Credits) Quantum states as vectors; spin and spectroscopy, multiparticle systems, Classical experiments in atomic physics and more sophisticated the periodic table, perturbation theory, band structure, etc. experiments in current techniques in nuclear physics. Prerequisite: PHYS401. Prerequisite: PHYS405. PHYS404 Introduction to Statistical Thermodynamics (3 Credits) PHYS431 Introduction to Solid State Physics (3 Credits) Introduction to basic concepts in thermodynamics and statistical Classes of materials; introduction to basic ideal and real materials' mechanics. behavior including mechanical, electrical, thermal, magnetic and optical Prerequisite: PHYS371 or PHYS420. responses of materials; importance of microstructure in behavior. One PHYS405 Advanced Experiments (3 Credits) application of each property will be discussed in detail. Advanced laboratory techniques. Selected experiments from many fields Prerequisite: PHYS271, PHYS270, and MATH241. of modern physics. Emphasis on self-study of the phenomena, data Restriction: Junior standing or higher; and must be in the Engineering: analysis, and presentation in report form. -

Bell's Theorem and Its First Experimental Tests

ARTICLE IN PRESS Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 37 (2006) 577–616 www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsb Philosophy enters the optics laboratory: Bell’s theorem and its first experimental tests (1965–1982) Olival Freire Jr. Instituto de Fı´sica, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, BA 40210-340, Brazil Received 27 June 2005; received in revised form 22 November 2005; accepted 2 December 2005 Abstract This paper deals with the ways that the issue of completing quantum mechanics was brought into laboratories and became a topic in mainstream quantum optics. It focuses on the period between 1965, when Bell published what we now call Bell’s theorem, and 1982, when Aspect published the results of his experiments. Discussing some of those past contexts and practices, I show that factors in addition to theoretical innovations, experiments, and techniques were necessary for the flourishing of this subject, and that the experimental implications of Bell’s theorem were neither suddenly recognized nor quickly highly regarded by physicists. Indeed, I will argue that what was considered good physics after Aspect’s 1982 experiments was once considered by many a philosophical matter instead of a scientific one, and that the path from philosophy to physics required a change in the physics community’s attitude about the status of the foundations of quantum mechanics. r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: History of physics; Quantum physics; Bell’s theorem; Entanglement; Hidden-variables; Scientific controversies 1. Introduction Quantum non-locality, or entanglement, that is the quantum correlations between systems (photons, electrons, etc.) that are spatially separated, is the key physical effect in the burgeoning and highly funded search for quantum cryptography and computation.