The Art of Pedaling - Advanced Use of Pedal in Different Styles of Music, and How It Relates to Technique, Dynamics and Articulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

Basic Dynamic Markings

Basic Dynamic Markings • ppp pianississimo "very, very soft" • pp pianissimo "very soft" • p piano "soft" • mp mezzo-piano "moderately soft" • mf mezzo-forte "moderately loud" • f forte "loud" • ff fortissimo "very loud" • fff fortississimo "very, very loud" • sfz sforzando “fierce accent” • < crescendo “becoming louder” • > diminuendo “becoming softer” Basic Anticipation Markings Staccato This indicates the musician should play the note shorter than notated, usually half the value, the rest of the metric value is then silent. Staccato marks may appear on notes of any value, shortening their performed duration without speeding the music itself. Spiccato Indicates a longer silence after the note (as described above), making the note very short. Usually applied to quarter notes or shorter. (In the past, this marking’s meaning was more ambiguous: it sometimes was used interchangeably with staccato, and sometimes indicated an accent and not staccato. These usages are now almost defunct, but still appear in some scores.) In string instruments this indicates a bowing technique in which the bow bounces lightly upon the string. Accent Play the note louder, or with a harder attack than surrounding unaccented notes. May appear on notes of any duration. Tenuto This symbol indicates play the note at its full value, or slightly longer. It can also indicate a slight dynamic emphasis or be combined with a staccato dot to indicate a slight detachment. Marcato Play the note somewhat louder or more forcefully than a note with a regular accent mark (open horizontal wedge). In organ notation, this means play a pedal note with the toe. Above the note, use the right foot; below the note, use the left foot. -

Articulation from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Articulation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Examples of Articulations: staccato, staccatissimo,martellato, marcato, tenuto. In music, articulation refers to the musical performance technique that affects the transition or continuity on a single note, or between multiple notes or sounds. Types of articulations There are many types of articulation, each with a different effect on how the note is played. In music notation articulation marks include the slur, phrase mark, staccato, staccatissimo, accent, sforzando, rinforzando, and legato. A different symbol, placed above or below the note (depending on its position on the staff), represents each articulation. Tenuto Hold the note in question its full length (or longer, with slight rubato), or play the note slightly louder. Marcato Indicates a short note, long chord, or medium passage to be played louder or more forcefully than surrounding music. Staccato Signifies a note of shortened duration Legato Indicates musical notes are to be played or sung smoothly and connected. Martelato Hammered or strongly marked Compound articulations[edit] Occasionally, articulations can be combined to create stylistically or technically correct sounds. For example, when staccato marks are combined with a slur, the result is portato, also known as articulated legato. Tenuto markings under a slur are called (for bowed strings) hook bows. This name is also less commonly applied to staccato or martellato (martelé) markings. Apagados (from the Spanish verb apagar, "to mute") refers to notes that are played dampened or "muted," without sustain. The term is written above or below the notes with a dotted or dashed line drawn to the end of the group of notes that are to be played dampened. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

On Teaching the History of Nineteenth-Century Music

On Teaching the History of Nineteenth-Century Music Walter Frisch This essay is adapted from the author’s “Reflections on Teaching Nineteenth- Century Music,” in The Norton Guide to Teaching Music History, ed. C. Matthew Balensuela (New York: W. W Norton, 2019). The late author Ursula K. Le Guin once told an interviewer, “Don’t shove me into your pigeonhole, where I don’t fit, because I’m all over. My tentacles are coming out of the pigeonhole in all directions” (Wray 2018). If it could speak, nineteenth-century music might say the same ornery thing. We should listen—and resist forcing its composers, institutions, or works into rigid categories. At the same time, we have a responsibility to bring some order to what might seem an unmanageable segment of music history. For many instructors and students, all bets are off when it comes to the nineteenth century. There is no longer a clear consistency of musical “style.” Traditional generic boundaries get blurred, or sometimes erased. Berlioz calls his Roméo et Juliette a “dramatic symphony”; Chopin writes a Polonaise-Fantaisie. Smaller forms that had been marginal in earlier periods are elevated to unprecedented levels of sophistication by Schubert (lieder), Schumann (character pieces), and Liszt (etudes). Heightened national identity in many regions of the European continent resulted in musical characteristics which become more identifiable than any pan- geographic style in works by composers like Musorgsky or Smetana. At the college level, music of the nineteenth century is taught as part of music history surveys, music appreciation courses, or (more rarely these days) as a stand-alone course. -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

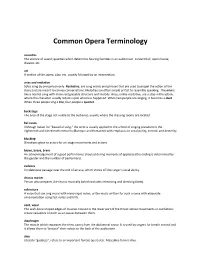

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

Romantic Music 1810 – 1900

Romantic Music 1810 – 1900 Key Characteristics • A thick texture • Wide range and contrast in dynamics and pitch • Long expressive melodies • Rich harmonies • A large orchestra – a variety of Percussion is now common • Use of recurring themes – Leitmotiv • Nationalism Romantic Orchestra • Orchestra size became the size it is today. • Strings – many more players (plus the Harp) • Brass – introduction of trombone and tuba • Woodwind – more in number (piccolo,cor anglais, bass clarinet and contrabassoon) • Percussion – 3 or more timpani, plus lots of other percussion instruments Symphony • A work for full orchestra • The Classical Symphony usually followed the pattern of 4 movements. • However, in the Romantic era some composers extended this to include 5 movements, • Some experimented with the addition of voices. • In both of the above examples the use of expression through dynamics, modulation and size of orchestra was significant. Concerto • A work for soloist and orchestra • In the Romantic era the Orchestra took a more prominent role in the Solo Concerto. • In Classical music it had played the accompanying part – in Romantic times it became equal with the soloist. • Romantic Orchestra became equal with the soloist Programme Music • Music which tells a story or describes a scene. • This was music composed for the purpose of telling a story or describing a mood or scene from a picture or piece of poetry. • Instruments and harmonies were assigned to certain emotions or characters within the story/picture. • Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony • Composed in 1808 • Beethoven said that the symphony was “more the expression of feeling than painting” • Berlioz composed his Symphonie Fantastique where one melody is used to symbolise a person throughout each movement. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Music Is Made up of Many Different Things Called Elements. They Are the “I Feel Like My Kind Building Bricks of Music

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – BUILDING BRICKS 5 MINUTES READING #1 Music is made up of many different things called elements. They are the “I feel like my kind building bricks of music. When you compose a piece of music, you use the of music is a big pot elements of music to build it, just like a builder uses bricks to build a house. If of different spices. the piece of music is to sound right, then you have to use the elements of It’s a soup with all kinds of ingredients music correctly. in it.” - Abigail Washburn What are the Elements of Music? PITCH means the highness or lowness of the sound. Some pieces need high sounds and some need low, deep sounds. Some have sounds that are in the middle. Most pieces use a mixture of pitches. TEMPO means the fastness or slowness of the music. Sometimes this is called the speed or pace of the music. A piece might be at a moderate tempo, or even change its tempo part-way through. DYNAMICS means the loudness or softness of the music. Sometimes this is called the volume. Music often changes volume gradually, and goes from loud to soft or soft to loud. Questions to think about: 1. Think about your DURATION means the length of each sound. Some sounds or notes are long, favourite piece of some are short. Sometimes composers combine long sounds with short music – it could be a song or a piece of sounds to get a good effect. instrumental music. How have the TEXTURE – if all the instruments are playing at once, the texture is thick. -

Music Appreciation Mus-100 Unit 5 Study Guide

MUSIC APPRECIATION MUS-100 UNIT 5 STUDY GUIDE 1. What was the span of time in which the Romantic era occurred? 2. Describe the melodies of the Romantic period. 3. What term was used by Romantic composers to indicate a flexible tempo that was to be determined by the performer? 4. Describe the harmonies of the Romantic era. 5. What was the most important ‘instrument’ of the Romantic period? 6. How did the Romantic orchestra compare in size to that of the Classic orchestra? 7. What is a general term for any piece of music associated with a story or extra-musical idea? 8. What controlled most of the elements in Romantic music? 9. How were dynamics employed in Romantic music? 10. What is the musical term for a short Romantic piece, lasting only a few minutes and is usually written for piano or voice? 11. Describe the use of tempo in Romantic music. 12. What is the musical term for ‘robbed time?' 13. Describe the use of form in Romantic music. 14. Instead of rigid forms, what type of music did most composers write? 15. What is the musical term for writing that invoved the use of various instruments to produce an effective and total orchestral sound? 16. How was the form of Romantic music determined? 17. What piano genre is a Polish national dance? 18. What musical era used chromaticism the most? 19. Which of the other ‘arts’ had the greatest influence on the early Romantic composers? 20. Which country produced Romantic nationalistic music? 21. Who were three early Romantic composers of piano miniatures? 22. -

Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 3 Number 2 Fall Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Kauffman, Deborah (1992) "Portamento in Romantic Opera," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 3. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.199205.02.03 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Romantic Ornamentation Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman Present day singing differs from that of the nineteenth century in a num- ber of ways. One of the most apparent is in the use of portamento, the "carrying" of the tone from one note to another. In our own century portamento has been viewed with suspicion; as one author wrote in 1938, it is "capable of much expression when judiciously employed, but when it becomes a habit it is deplorable, because then it leads to scooping."1 The attitude of more recent authors is difficult to ascertain, since porta- mento has all but disappeared as a topic for discussion in more recent texts on singing. Authors seem to prefer providing detailed technical and physiological descriptions of vocal production than offering discussions of style. But even a cursory listening of recordings from the turn of the century reveals an entirely different attitude toward portamento.