Cambridge Section of the Waikato Expressway: Archaeological Desktop Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finance & Corporate Public Agenda

Finance & Corporate Public Agenda - 20 April 2021 - Agenda Finance & Corporate Public Agenda - 20 April 2021 Council Chambers Waipa District Council 101 Bank Street Te Awamutu Chairperson AW Brown Members His Worship the Mayor JB Mylchreest, EM Andree-Wiltens, EH Barnes, LE Brown, PTJ Coles, RDB Gordon, ML Gower, B Koroheke (Te Kanohi Representative), SC O’Regan, MJ Pettit, EM Stolwyk, CS St Pierre, BS Thomas, GRP Webber 20 April 2021 01:00 PM - 02:10 PM Agenda Topic Presenter Time Page 1. Apologies Chairperson 01:00 PM-01:01 PM 3 2. Disclosure of Members’ Interests Chairperson 01:01 PM-01:02 PM 4 3. Late Items Chairperson 01:02 PM-01:03 PM 5 4. Confirmation of Order of Meeting Chairperson 01:03 PM-01:04 PM 6 5. Confirmation of Minutes Chairperson 01:04 PM-01:05 PM 7 5.1 Finance & Corporate Committee Chairperson 8 Minutes - 30 March 2021 6. Cambridge Town Hall Community Trust Bev Gatenby 01:05 PM-01:20 PM 17 Appointments 7. Financial Report for the Period Ended 31 Nada Milne 01:20 PM-01:40 PM 22 March 2021 8. Targa 2021 - Request for Temporary Road Julie Taylor 01:40 PM-01:43 PM 33 Closure 9. Receiving of Mighty River Domain 2020 Liz Stolwyk 01:43 PM-02:03 PM 40 Annual Report 1 Finance & Corporate Public Agenda - 20 April 2021 - Agenda 10. Resolution to Exclude the Public Chairperson 02:03 PM-02:05 PM 51 2 Finance & Corporate Public Agenda - 20 April 2021 - Apologies APOLOGIES Recommendation That the apologies for non-attendance from Councillors CS St Pierre and EM Andree- Wiltens be received. -

Lake Te Koo Utu Ecology, Stormwater Management and Restoration Options Prepared for Waipa District Council

Lake Te Koo Utu Ecology, stormwater management and restoration options Prepared for Waipa District Council 3 April 2020 Document Set ID: 10372718 Version: 3, Version Date: 17/04/2020 Document Quality Assurance Bibliographic reference for citation: Boffa Miskell Limited 2020. Lake Te Koo Utu: Ecology, stormwater management and restoration options. Report prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited for Waipa District Council. Prepared by: Andrew Blayney Ecologist – Associate Principal Boffa Miskell Limited Mike Chapman Water Resources Specialist Te Miro Water Consultants Ecology Inputs Kieran Miller Reviewed by: Ecologist – Associate Principal Boffa Miskell Limited Status: Final Revision / version: [1.1] Issue date: 3 April 2020 Use and Reliance This report has been prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited on the specific instructions of our Client. It is solely for our Client’s use for the purpose for which it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. Boffa Miskell does not accept any liability or responsibility in relation to the use of this report contrary to the above, or to any person other than the Client. Any use or reliance by a third party is at that party's own risk. Where information has been supplied by the Client or obtained from other external sources, it has been assumed that it is accurate, without independent verification, unless otherwise indicated. No liability or responsibility is accepted by Boffa Miskell Limited for any errors or omissions to the extent that they arise from inaccurate information provided by the Client -

Waipa Cemetery Locations

Abergeldie Way G3 Hautapu Road G3 Paterangi Road D4-E5 Airport Road E2 Hawthorne Road D5 Patterson Road C4 A B C D E F G H I J Akatarere Road I7 Head Road I5 Payne Road F6 Allcock Road C4 Herman Road E3 Peake Road G2-G3 Alexander Road C6 Hewson Road H5 Penniket Road E3 Allen Road E6 Hickey Road H3 Perrin Road D4 Allwill Drive G3 Hicks Road I5 Perrott Road I8 1 Hamilton Amber Lane I4 Higham Road F6 Pickering Road G2 1 Anderson Road C4 Hill Road J5 Pirongia Road C5-E5 Waikato City Andrew Road G7 Hodgson Road C4 Plantation Road J5 Te Miro Hogan Road G3 Pokuru Factory Road D6 District Scenic Reserve Angus Road F3 Aotearoa Road H8-I9 Holmwood Drive C3 Pokuru Road C6-E6 Appleby Road G3 Houchen Road D2 Puahue Road F6-G6 Puahue Quarry Road G6 Arapuni Lake Road I7-J8 Ingram Road E3 Arapuni Road F6-17 Pukerimu Lane G3 Matamata- Arthur Road B4 Jary Road E4-F4 Waikato Aspin Road H2-H3 John Hewitt Drive I4 Quarry Road A3 Piako Awanui Avenue E6 Johnson Road D5 District Judd Lane H4 Racecourse Road (CB) G3 District Judge Road G6 Racecourse Road (TA) E5 2 2 Baker Road I2-I3 Rahiri Road H5 Lake Koromatua Bank Road D5 Jury Road C2 Wildlife Management Reserve Ranby Roadh E4 Barrett Road C2 Rangioawhia Road Kahuwera Road H7 F6 Bayley Road G7 Ray Road Kaipaki Road E3-G3 D6 Bell Road C4 Raynes Road Kairangi Road G5-H6 E2 Benn Road H4 Redoubt Road Kakaramea Road C2-C5 H4 Berkers Road C2 Reid Road Maungakawa Kakepuku Road D7 C3 Scenic Reserve Berquist Road F3 Reynolds Road G4 Kaniwhaniwha Karapiro Road I4 Scenic Reserve Bird Road C5 Rice Road Karl Road E4 C4 -

Programme 22-27 January 2019

PROGRAMME 22-27 JANUARY 2019 www.ridewaikato.co.nz @ride_cycling_festival_nz /ride2019 CELEBRATE THE RIDE! We are passionate about this region and believe that The Three Peaks RIDE New cycling is one of the best ways to explore our stunning landscapes, to stay healthy and active, to socialise with Zealand’s Cycling Festival friends and family, and quite simply to have a lot of fun! is a world-class, week-long We have created this event to showcase the wonders of cycling – from the highest level of competitive sport to the festival of cycling for widest possible community participation events – RIDE people of all ages and literally has something for everyone. stages. We invite you to take in the vibrant atmosphere and cheer on the pros as they take on the UCI 2.2 Grassroots Trust New Zealand Cycle Classic – or better yet, get on a bike yourself and ride the inaugural Hobbiton Movie Set Gran Fondo. Whether you are seasoned cyclist, a beginner or just keen to see what it’s all about, join us for a week of ‘all things cycling’ in the Waipa District from 22 January to 27 January 2019. On behalf of the event organising committee, I look forward to celebrating the RIDE with you! For a full list of event happenings each day check out the event schedule at ridewaikato.co.nz Simon Perry Chairman RIDE: New Zealand’s Cycling Festival Awe inspiring. Life enriching. From a remote active volcanic plateau comes the world’s most magnificent Manuka honey. Enrich life everyday. www.threepeaksnz.com WELCOME TO WAIPA We are delighted to have this outstanding event in our Welcome to the Waipa district and to welcome teams and spectators from New Zealand and around the world. -

Management of Wetland Archaeological Sites in New Zealand

5. Case studies 5.1 KAURI POINT SWAMP The Kauri Point swamp is a true swamp. It is fed by mineral-rich ground water, is eutrophic, and moderately acid—no more than pH 5.8 (Shawcross 1976: 281– 282). The swamp is essentially Y-shaped with a main arm and slightly smaller tributary arm. Both arms are fed by perennial springs, which are augmented, to some extent, by run-off from the ground surface during rain. However, the surrounding volcanic ash soils are free draining and much of the rain probably feeds the springs via the ground water-table. For most of its length the swamp is less than 10 m wide, usually about 5 m, but narrower for the lower 40 m (adjacent to the pa) where it cuts down to a narrower channel. Just above this, at the junction of the two branches, the swamp is wider— approximately 15 m. Immediately below the junction of the two arms is where the swamp excavation was made. The head of the main arm of the swamp (where the principal springs are located), is vegetated above a culverted causeway. The vegetation is predominantly willow, but includes manuka, cordyline, ferns, grasses, raupo, rushes, cress, and arum lily. The vegetation continues below the causeway for approximately 50 m, but here it is less diverse with a large clump of raupo Figure 4. Locations of Lake above a large grove of willow. Below the willows the diversity of vegetation Mangakaware and Owarau declines and it is mainly grasses and rushes. Pa (Kauri Point) swamp. -

Contents Kia Ora and Welcome

Lake Rotoroa, Hamilton Contents Kia Ora and Welcome ...............................................................2 Our City .....................................................................................4 Middle-earth Movie Magic .........................................................5 Underground Wonders ..............................................................6 Outdoor Adventures ..................................................................7 Top 10 Family Fun Activities ......................................................8 Arts & Culture and Shop Up A Storm ........................................9 Gourmet Delights ....................................................................10 Your Business Events Destination ............................................11 Cycle Trails .............................................................................. 12 Walking and Hiking Trails ........................................................ 14 Where to Stay, Our Climate, Getting Around ..........................16 Thermal Explorer Highway and Itinerary Suggestions ............ 17 Useful Information, Visit our Website ......................................18 What’s On - Events .................................................................19 Hamilton CBD Map .................................................................49 Waikato Regional Map ......................................... Cover Section North Waikato ........................................................................ 26 Hamilton................................................................................ -

Waipā Heritage Trail Brochure

Symbols Walking Tracks Toilets Site on private land. Access permission required. All other sites are visible from the road or are accessible to the public. Published By Waipa District Council / Waipa Heritage and Biodiversity Committee Private Bag Cambridge Copyright 2008 Design What’s the Story Publications ISBN: 978-0-473-14254-4 Welcome to the... Waipā DISTRICT HERITAGE TRAIL This heritage trail traces the rich history of the Waipā region. Included are sites of Māori and European settlements, battle sites, trading posts, and places that have played a significant part in the development of Waipā District. For ease of use they are listed in two sections: West Waipā and East Waipā. Within these sections, the sites are listed as much as possible in the order you might find them travelling north to south. If we were to cover every Waipā site of historical interest this would become a large book not an easy-use guide. Instead the aim has been to cover a broad selection. Historical sites in Te Awamutu and Cambridge have been excluded as these are covered in other publications. WEST WAIPA EAST WAIPA pages 2-13 pages 18-29 To Hamilton Cambridge Pirongia Te Awamutu To Otorohonga Full map on page 14 1 1 Harapepe District Harapepe was originally settled by the chief Māhanga, descendant of the occupants of the Tainui canoe. He lived at Pūrākau, a pā at the confluence of Kaniwhaniwha Stream and the Waipā River. Following the land war in the mid 1860s, Ngāti Māhanga land was confiscated and offered to British soldiers (the second company of Forest Rangers under Major Von Tempsky) in one acre residential grants plus 50 acres of farming land. -

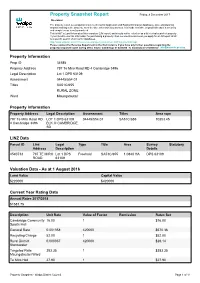

Property Snapshot Report Friday, 8 December 2017

Property Snapshot Report Friday, 8 December 2017 Disclaimer The property report is a snapshot of selected Council Application and Rating Information databases, zone and planning maps pertaining to the property, as at the date this report is generated. It is made available in good faith and it’s accuracy and completeness is not guaranteed. This is NOT a Land Information Memorandum (LIM report) and should not be relied on as a full clerical search of property . If you intend to use this information for purchasing a property, then we would recommend you apply for a LIM report which is a specific search of all council databases. http://www.waipadc.govt.nz/our-services/property-and-rates/LIM/Pages/default.aspx Please contact the Revenue Department in the first instance if you have any further questions regarding the property snapshot report during office hours: Cambridge 07 8233800 Te Awamutu 07 8720030 or [email protected] Property Information Prop ID 34588 Property Address 797 Te Miro Road RD 4 Cambridge 3496 Legal Description Lot 1 DPS 63109 Assessment 04445/554.01 Titles SA51C/655 RURAL ZONE Ward Maungatautari Property Information Property Address Legal Description Assessment Titles Area sqm 797 Te Miro Road RD LOT 1 DPS 63109 04445/554.01 SA51C/655 10853.45 4 Cambridge 3496 BLK III CAMBRIDGE SD LINZ Data Parcel ID Linz Legal Type Title Area Survey Statutory Address Description Details 4540733 797 TE MIRO Lot 1 DPS Freehold SA51C/655 1.0840 HA DPS 63109 ROAD 63109 Valuation Data - As at 1 August 2016 Land Value Capital Value $220000 -

Annual Report 2009/10

HAMILTON CITY COUNCIL’S 2009/10 ANNUAL REPORT the year in review Whakatauki and He Mihi Kotahi ano te kohao te ngira E kuhuna ai te miro ma, te miro whero Me te miro pango. A muri I a au kia mau ki te ture, Ki te whakapono, ki te aroha. Hei aha te aha! Hei aha te aha! There is but one eye of the needle Through which the white, red and black threads must pass. After me obey the commandments, keep faith, And hold fast to love and charity Forsake all else. Nga take I koreohia a tatau I mua Tui ai te kupu korero I korerotia Kia tu te winiwini kia tu te wanawana I nga pu korero I wanangatia I roto I te whai ao I te ao marama. We bring our combined history and past discussions Into our plans here for the future. Be open and stand strongly For the issues considered and discussed, To benefit the world, now and in the future. Na Potatau Te Wherowhero, 1858 the year in review Hamilton City Council Municipal Offices Garden Place Private Bag 3010 Hamilton 3420 New Zealand Phone +64 (0)7 838 6699 Fax +64 (0)7 838 6599 Email [email protected] www.hamilton.co.nz ISSN 1171-316X CONTENTS i CONTENTS 1.0 Message from the Mayor and Chief 4.9 Waste Minimisation………………………. 95 Executive…………………………..................... 1 Refuse and Recycling……………………… 95 4.10 Water Management……………………... 99 2.0 Overview of Council’s Performance in 3 Water Supply………………………………. 99 2009/10.……….……………………………….. Wastewater………………………………… 102 Stormwater…………………………………. 104 3.0 Strategic Direction…..……..……….…..... -

Greening Cambridge’

Towards ‘Greening Cambridge’ Supporting Predator Free Cambridge - helping to make our dawn chorus a symphony November 2018 Prepared by Better Biosecurity Solutions Ltd, November 2018 - Predator Free Cambridge This pre-scoping strategy/framework document has been reviewed and approved for release by: __________________________ P G Russell 19th November 2018 Cover photograph: Large female possum trapped in Hall Street, Cambridge – June 2018 (Photo source: P Russell) Acknowledgements The following people and organisations are thanked for their assistance in preparing this document: • Susan Emmitt, Claudia Gawler – Waipa District Council • Dion Patterson, Tania Wells, Carisse Enderwick, Rose DouglasGraham, Andrew Styche – Dept of Conservation • Dave Byers, Mark Gasquoine – Waikato Regional Council • Alex Daniel, Environmental Educator, Enviroschools/Trees for Survival • Members of the wider Cambridge community (Adam Thompson, Joe Dillon, Donna Palmer, David Griffith and Bella and Niki Russell) currently undertaking predator control/raising awareness (keep up the great work!) Disclaimer: This document has been prepared and written by Better Biosecurity Solutions Ltd for the Department of Conservation and Predator Free Cambridge, to ultimately better engage with schools but also businesses and the wider Cambridge community. The document is intended to provide accurate and adequate information pertaining to the subject matters, within the limitations of the project scope. While every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this