The Whole Chord Thing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIC THEORY UNIT 5: TRIADS Intervallic Structure of Triads

MUSIC THEORY UNIT 5: TRIADS Intervallic structure of Triads Another name of an interval is a “dyad” (two pitches). If two successive intervals (3 notes) happen simultaneously, we now have what is referred to as a chord or a “triad” (three pitches) Major and Minor Triads A Major triad consists of a M3 and a P5 interval from the root. A minor triad consists of a m3 and a P5 interval from the root. Diminished and Augmented Triads A diminished triad consists of a m3 and a dim 5th interval from the root. An augmented triad consists of a M3 and an Aug 5th interval from the root. The augmented triad has a major third interval and an augmented fifth interval from the root. An augmented triad differs from a major triad because the “5th” interval is a half-step higher than it is in the major triad. The diminished triad differs from minor triad because the “5th” interval is a half-step lower than it is in the minor triad. Recommended process: 1. Memorize your Perfect 5th intervals from most root pitches (ex. A-E, B-F#, C-G, D-A, etc…) 2. Know that a Major 3rd interval is two whole steps from a root pitch If you can identify a M3 and P5 from a root, you will be able to correctly spell your Major Triads. 3. If you need to know a minor triad, adjust the 3rd of the major triad down a half step to make it minor. 4. If you need to know an Augmented triad, adjust the 5th of the chord up a half step from the MAJOR triad. -

A Group-Theoretical Classification of Three-Tone and Four-Tone Harmonic Chords3

A GROUP-THEORETICAL CLASSIFICATION OF THREE-TONE AND FOUR-TONE HARMONIC CHORDS JASON K.C. POLAK Abstract. We classify three-tone and four-tone chords based on subgroups of the symmetric group acting on chords contained within a twelve-tone scale. The actions are inversion, major- minor duality, and augmented-diminished duality. These actions correspond to elements of symmetric groups, and also correspond directly to intuitive concepts in the harmony theory of music. We produce a graph of how these actions relate different seventh chords that suggests a concept of distance in the theory of harmony. Contents 1. Introduction 1 Acknowledgements 2 2. Three-tone harmonic chords 2 3. Four-tone harmonic chords 4 4. The chord graph 6 References 8 References 8 1. Introduction Early on in music theory we learn of the harmonic triads: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. Later on we find out about four-note chords such as seventh chords. We wish to describe a classification of these types of chords using the action of the finite symmetric groups. We represent notes by a number in the set Z/12 = {0, 1, 2,..., 10, 11}. Under this scheme, for example, 0 represents C, 1 represents C♯, 2 represents D, and so on. We consider only pitch classes modulo the octave. arXiv:2007.03134v1 [math.GR] 6 Jul 2020 We describe the sounding of simultaneous notes by an ordered increasing list of integers in Z/12 surrounded by parentheses. For example, a major second interval M2 would be repre- sented by (0, 2), and a major chord would be represented by (0, 4, 7). -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music

1 Kristen Masada and Razvan Bunescu: A Segmental CRF Model for Chord Recognition in Symbolic Music A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music minished triads most frequently contain a diminished A chord is a group of notes that form a cohesive har- seventh interval (9 half steps), producing a fully di- monic unit to the listener when sounding simulta- minished seventh chord, or a minor seventh interval, neously (Aldwell et al., 2011). We design our sys- creating a half-diminished seventh chord. tem to handle the following types of chords: triads, augmented 6th chords, suspended chords, and power A.2 Augmented 6th Chords chords. An augmented 6th chord is a type of chromatic chord defined by an augmented sixth interval between the A.1 Triads lowest and highest notes of the chord (Aldwell et al., A triad is the prototypical instance of a chord. It is 2011). The three most common types of augmented based on a root note, which forms the lowest note of a 6th chords are Italian, German, and French sixth chord in standard position. A third and a fifth are then chords, as shown in Figure 8 in the key of A minor. built on top of this root to create a three-note chord. In- In a minor scale, Italian sixth chords can be seen as verted triads also exist, where the third or fifth instead iv chords with a sharpened root, in the first inversion. appears as the lowest note. The chord labels used in Thus, they can be created by stacking the sixth, first, our system do not distinguish among inversions of the and sharpened fourth scale degrees. -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

Harmonic Expectation in Twelve-Bar Blues Progressions Bryn Hughes

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Harmonic Expectation in Twelve-Bar Blues Progressions Bryn Hughes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC HARMONIC EXPECTATION IN TWELVE-BAR BLUES PROGRESSIONS By BRYN HUGHES A dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Bryn Hughes defended on July 1, 2011. ___________________________________ Nancy Rogers Professor Directing Dissertation ___________________________________ Denise Von Glahn University Representative ___________________________________ Matthew Shaftel Committee Member ___________________________________ Clifton Callender Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Evan Jones, Chair, Department of Music Theory and Composition _____________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii To my father, Robert David Moyse, for teaching me about the blues, and to the love of my life, Jillian Bracken. Thanks for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before thanking anyone in particular, I would like to express my praise for the Florida State University music theory program. The students and faculty provided me with the perfect combination of guidance, enthusiasm, and support to allow me to succeed. My outlook on the field of music theory and on academic life in general was profoundly shaped by my time as a student at FSU. I would like to express my thanks to Richard Parks and Catherine Nolan, both of whom I studied under during my time as a student at the University of Western Ontario and inspired and motivated me to make music theory a career. -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

The Guitar, the Steamship and the Picnic: England on the Move Transcript

The Guitar, the Steamship and the Picnic: England on the Move Transcript Date: Thursday, 11 December 2014 - 1:00PM Location: St. Sepulchre Without Newgate 11 December 2014 The Guitar, the Steamship and the Picnic: England on the Move Professor Christopher Page I would like to begin with a poem by William Blake, first published in his collection Songs of Innocence in 1789. Many of you will know it; it is entitled The Chimney Sweeper, and you have it, in Blake’s illustrated copy, on the first page of your handout: When my mother died I was very young, And my father sold me while yet my tongue Could scarcely cry weep! weep! weep! weep! So your chimneys I sweep & in soot I sleep. There’s little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head That curled like a lamb’s back, was shaved, so I said, “Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head’s bare, You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair.” And so he was quiet, and that very night, As Tom was a-sleeping he had such a sight! That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned, & Jack, Were all of them locked up in coffins of black; And by came an Angel who had a bright key, And he opened the coffins & set them all free; Then down a green plain, leaping, laughing they run, And wash in a river and shine in the Sun. Then naked and white, all their bags left behind, They rise upon clouds, and sport in the wind. And the Angel told Tom, if he’d be a good boy, He'd have God for his father & never want joy. -

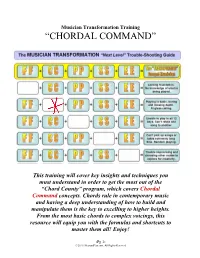

“Chordal Command”

Musician Transformation Training “CHORDAL COMMAND” This training will cover key insights and techniques you must understand in order to get the most out of the “Chord County” program, which covers Chordal Command concepts. Chords rule in contemporary music and having a deep understanding of how to build and manipulate them is the key to excelling to higher heights. From the most basic chords to complex voicings, this resource will equip you with the formulas and shortcuts to master them all! Enjoy! -Pg 1- © 2010. HearandPlay.com. All Rights Reserved Introduction In this guide, we’ll be starting with triads and what I call the “FANTASTIC FOUR.” Then we’ll move on to shortcuts that will help you master extended chords (the heart of contemporary playing). After that, we’ll discuss inversions (the key to multiplying your chordal vocaluary), primary vs secondary chords, and we’ll end on voicings and the difference between “voicings” and “inversions.” But first, let’s turn to some common problems musicians encounter when it comes to chordal mastery. Common Problems 1. Lack of chordal knowledge beyond triads: Musicians who fall into this category simply have never reached outside of the basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) and are stuck playing the same chords they’ve always played. There is a mental block that almost prohibits them from learning and retaining new chords. Extra effort must be made to embrace new chords, no matter how difficult and unusual they are at first. Knowing the chord formulas and shortcuts that will turn any basic triad into an extended chord is the secret. -

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications Minseon Song May 17, 2014 Abstract Transformational theory is a modern branch of music theory developed by David Lewin. This theory focuses on the transformation of musical objects rather than the objects them- selves to find meaningful patterns in both tonal and atonal music. A generalized interval system is an integral part of transformational theory. It takes the concept of an interval, most commonly used with pitches, and through the application of group theory, generalizes beyond pitches. In this paper we examine generalized interval systems, beginning with the definition, then exploring the ways they can be transformed, and finally explaining com- monly used musical transformation techniques with ideas from group theory. We then apply the the tools given to both tonal and atonal music. A basic understanding of group theory and post tonal music theory will be useful in fully understanding this paper. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 A Crash Course in Music Theory 2 3 Introduction to the Generalized Interval System 8 4 Transforming GISs 11 5 Developmental Techniques in GIS 13 5.1 Transpositions . 14 5.2 Interval Preserving Functions . 16 5.3 Inversion Functions . 18 5.4 Interval Reversing Functions . 23 6 Rhythmic GIS 24 7 Application of GIS 28 7.1 Analysis of Atonal Music . 28 7.1.1 Luigi Dallapiccola: Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera, No. 3 . 29 7.1.2 Karlheinz Stockhausen: Kreuzspiel, Part 1 . 34 7.2 Analysis of Tonal Music: Der Spiegel Duet . 38 8 Conclusion 41 A Just Intonation 44 1 1 Introduction David Lewin(1933 - 2003) is an American music theorist. -

Leo Carrillo California History & Art Program

LEO CARRILLO CALIFORNIA HISTORY & ART PROGRAM PROJECT TITLE: Fine-Tuning Guitar Art THEME: Spanish Guitar AGE: Fourth Grade PROJECT INTRODUCTION: Students will learn about the history of the classical Spanish guitar that was a part of the lifestyle at the Leo Carrillo Ranch. Students will be introduced to the famous Mexican folksong “La Golondrina”, a melody played on the guitar and cherished by Leo Carrillo. Students will create and design their own Spanish guitar inspired work of art through mixed media using collage and illustration, personalizing their artwork with intentional images and meaning. ART PROJECT INSPIRATION: SPANISH GUITAR The guitar is one of the most popular and widespread musical instruments played today. It is actually the second most played instrument, with the first being the piano. A person who makes guitars is called a “luthier”. A person who plays the guitar is called a “guitarist”. Guitarists play the guitar by plucking or strumming the strings with their fingers, fingernails, or a pick. There are several types of guitars: Classical, Electric, Steel, Flamenco, 12 String and many more. It was the classical guitar, also known as the Spanish guitar that had a special presence at the Leo Carrillo Ranch. Music played on the Spanish guitar reminded Leo Carrillo of his family history and was very much a part of the life he experienced as a child growing up. The word guitar was adopted into English from the Spanish word “guitarra” in the 1600’s. The country of Spain has had an extraordinary impact on the development of the classical guitar. Spaniards in Andalusia during the 1790’s took the guitar to new heights when they added a sixth string to it.