Labor Mobility and Racial Discrimination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BURTON ALBION Ground Name the Pirelli Stadium | Capacity 6,912 | Nickname the Brewers

AT THE RIVERSIDE LAURI COX and SAM LOUGHRAN introduce tonight’s opponents... BURTON ALBION www.burtonalbionfc.co.uk Ground Name The Pirelli Stadium | Capacity 6,912 | Nickname The Brewers 21 Hope Akpan Position: Midfielder Nationality: Nigerian DOB: 14.08.1991 Born in Childwall, Liverpool, Akpan made his competitive debut for Everton against BATE on 17 December 2009 in the UEFA Europa League. He came through the youth ranks at Everton and later played for Hull City (on loan), Crawley Town, Reading and Blackburn Rovers. Following his release by Blackburn, Akpan signed a one-year contract with Burton ONE TO Albion in July 2017. WATCH Though born in England, he represents Nigeria at international level. 43 Manager Nigel Clough Born in Sunderland and raised in Derby, Clough is most notable for his time as a player at Nottingham Forest, where he played over 400 times in league, cup and European matches in two separate spells, mostly under the managership of his father and Boro legend Brian, and scored 131 goals throughout his career, making him the second highest scorer in the club’s history. He subsequently had spells with Liverpool, Manchester City and Sheffield Wednesday before moving into non-league football at the age of 32 when he became player-manager with then Southern League Premier Division side Burton Albion in 1998. Over the next decade, during half of which he continued to play a regular role on the field, Clough took Burton up from the seventh tier of the English football league system to the brink of promotion to League Two before leaving halfway through the 2008–09 season to follow in his father’s footsteps and take over at Derby County, where he served for four years until September 2013. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

Back in Black ... and White!

Clap Your Hands, Stamp Your Feet £2.50 An independent view of Watford FC and football in general BACK IN BLACK ... AND WHITE! DOWNLOAD EDITION Please visit our Just Giving page and make a donation to The Bobby Moore Fund http://www.justgiving.com/CYHSYF Thank You! Geri says: “Good Lord! Are you Clap boys still going in glorious black and white? I may even pick up the mic and start miming again…” Credits The editorial team would like to extend their immense gratitude in no particular order to the following people, without whom this fanzine would not have been possible: Marvin Monroe Jay’s Mum Steve Cuthbert Tom Willis Woody Wyndham Josh Freedman Capt’n Toddy Martin & Frances Pipe Jamie Parkins (for the photos) Mike Parkin Hamish Currie Guy Judge Chris Lawton Martin Pollard Ed Messenger (since 1951) Tim Turner Bill Wilkinson our sellers Sam Martin and Ian Grant .. and of course to you our readers for buying it! Thanks a million! Barry and John While this edition is officially a ‘one off’ at the moment, if you would like to see Clap Your Hands Stamp Your Feet back on the streets at another date in future then please continue to send your padding to our email address over the next few months and if we get enough contributions we may yet be back in the springtime... yep, fairweather fanzine sellers - that’s us! [email protected] The views expressed in this fanzine are not necessarily shared by the editors and we take no responsibility for any offence or controversy arising from their publication. -

Al Parecer El PRI En Cancún Intenta Repetir La

Año 7 Número 1519 Lunes 09 de Julio de 2012 Edición Estatal José Luis González Mendoza no descarta que contienda de nuevo en un futuro cercano Al parecer el PRI en Cancún intenta repetir la misma historia de derrotas que vivió con el ex regidor Víctor Viveros Salazar, pues pese a que Laura Fernández Piña perdió la elección a diputada federal, la quieren catapultar para la presidencia municipal de Benito Juárez Pese a perder, ven a Laura como www.qrooultimasnoticias.com “candidata natural” Página 02 02 Ultimas Noticias de Quintana Roo CANCUN Lunes 09 de Julio de 2012 Pese a perder, ven a Laura como “candidata natural” Por Lucía Osorio CANCÚN.— Aún con la expe- riencia del pasado, el PRI en Be- nito Juárez no aprende, ya que al parecer intenta repetir la misma historia de derrotas que vivió con el ex regidor Víctor Viveros Sala- zar, pero ahora con Laura Fernán- dez Piña, quien a pesar de perder la elección a diputada federal, la catapultan para ser la candidata natural por la presidencia munici- pal de Cancún. El reciente nombrado presidente del PRI en Cancún, José Luis Gon- zález adelantó la ex candidata a la diputación por el Distrito 03, Laura Fernández Piña, “seguramente la veremos de nuevo contendiendo por algún cargo de elección popu- lar, sobre todo tomando en cuenta que sacó una buena votación”. Explicó que de no haber sido una campaña presidencial, se hu- biera ganado el municipio (en alu- sión al efecto Andrés Manuel Ló- pez Obrador, pues a su parecer la oposición no hizo una buena cam- paña) por el buen trabajo realiza- do, “pero no nos alcanzó”, acotó. -

2013 Uefa European Under-21 Championship 2011/13 Season Match Press Kit

2013 UEFA EUROPEAN UNDER-21 CHAMPIONSHIP 2011/13 SEASON MATCH PRESS KIT Israel England Group A - Matchday 3 Teddy Stadium, Jerusalem Tuesday 11 June 2013 18.00CET (19.00 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................3 Team facts.........................................................................................................................5 Squad list...........................................................................................................................7 Head coach.......................................................................................................................9 Match officials..................................................................................................................10 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................11 Competition facts.............................................................................................................12 Competition information..................................................................................................14 Legend............................................................................................................................15 Israel v England Tuesday 11 June 2013 - 18.00CET (19.00 local time) MATCH PRESS -

Getting Your

No. 37 / FEBRUARY 2019 GETTING YOUR MARVIN SORDELL TALKS ABOUT THE IMPORTANCE OF PUTTING MENTAL HEALTH FIRST PLUS DEBUTANTS • FEJIRI OKENABIRHIE • RAINBOW LACES • TALENTTouchline TRANSFER February 2019 1 Welcome to The FA Youth Cup is reaching brought to you by League Football Education its business end with eight EFL No. 37 / FEBRUARY 2019 WRITTEN BY JACK WYLIE | DESIGN BY ICG Academies still chasing silverware at the Round of 16 stage. One of the biggest scalps of this year’s tournament came TUESDAY 7TH MAY 2019 at the Wham Stadium, with Accrington Stanley’s Charlie Bradford City FC Ridge and Lewis Gilboy putting the home outfit 2-0 up Valley Parade inside six minutes against a strong Leeds United side, before eventually securing a 4-2 win after extra-time. That result booked a fourth round meeting with Liverpool, where their run ended as Stanley suffered a 4-0 defeat to the U18 Premier League North leaders, who will host WEDNESDAY 8TH MAY 2019 Wigan Athletic for a place in the last eight. Burton Albion FC The Latics produced the performance of Round Four with Pirelli Stadium a scintillating display at the KCom Stadium, hammering Hull City 6-2 thanks to a hat-trick from first-year apprentice Joe Gelhardt, as well as a double for Charlie Jolley, who Higher Education also found the net in a 2-1 win against Wolverhampton Wanderers at Molineux in the previous round. THURSDAY 9TH MAY 2019 If you’re thinking about going to University next September, LFE’s Higher Education Guide The lowest ranked club left in the competition are Sky Bet Woking FC provides extensive information League Two Bury, who have won back-to-back ties on the Laithwaite Community regarding the UCAS application road, winning 4-2 after extra-time against Stevenage before Stadium process, including Clearing and seeing off Peterborough United by a solitary goal. -

Intermediary Transactions 1February 2017 to 31 January 2018

27/03/2018 Premier League Intermediary Transactions 1 February 2017 to 31 January 2018 The information below represents all Transactions involving Clubs where an Intermediary was used from 1st February 2017 to 31 st January 2018. If the Intermediary was a company, they are listed in bold with their representative(s) in italics. If more than one intermediary acted on behalf of any of the parties (including subcontracts), they will be separated by "/". This information has been made publicly available in accordance with the requirements of the FIFA Regulations on Working with Intermediaries and The FA Regulations on Working with Intermediaries. The information has been included in good faith for football regulatory purposes only and no undertaking, representation or warranty (express or implied) is given as to its accuracy, reliability or completeness. We cannot guarantee that any information displayed has not been changed or modified through malicious attacks or “hacking”. Date Received Registering Club Player Player IM Player IM Organisation Registering Club IM Registering Club IM Organisation Former Club IM Former Club IM Organisation Former Club 01/02/17 AFC Bournemouth Ryan Fraser Jon McLeish Platinum One Sports Management Jon McLeish Platinum One Sports Management 24/05/17 AFC Bournemouth Steve Cook Marlon Fleischman Unique Sports Management Marlon Fleischman Unique Sports Management 22/06/17 AFC Bournemouth Harry Arter Paul Martin WMG Management Europe Ltd Paul Martin WMG Management Europe Ltd 30/06/17 AFC Bournemouth Asmir Begovic -

Cska Clinch Elm Signing

- 1 - Page 7 - OLYMPICS: Craig Bellamy strikes for Team GB NEWS HEADLINES pg. 3-6 OLYMPICS pg. 7-8 CHAMPIONS LEAGUE pg. 9 FRANCE: TROPHÉE DES CHAMPIONS pg. 10 RUSSIA: PREMIER LEAGUE pg. 11 BRAZIL: BRASILEIRÃO pg. 12-13 pg. 14 MEXICO: LIGA MX Page 10 – FRANCE: Lyon win Trophée des Champions USA: MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER pg. 15 TRANSFER ROUND-UP pg. 16-18 ARGENTINA: INICIAL PREVIEW pg. 19 Page 19 – ARGENTINA: Primera Division Preview - 2 - ENGLAND By reputation, Oscar operates in the classic Interestingly, the contrasts between the Brazilian No 10 role where his link play and success in signing Brazilians is quite stark THE BRAZILIAN between both Chelsea and United. Alex, individual-running threat should create a host of David Luiz and Ramires in particular, have all INVASION chances for Chelsea. proved productive at Stamford Bridge whereas Sir Alex’s strike rate with Brazilians, AS the Olympic football His current Olympic team-mate Lucas Moura and indeed many of his South American (pictured above) has, arguably, more buzz about signings, has been very poor. tournament begins to shift up him and already Sir Alex Ferguson has gone For all of Antonio Valencia’s positive through the gears two of public with his interest, a rare move by the contributions you need only look at Kleberson, Gabriel Heinze, Juan Veron and Manchester United manager who has also Brazil’s brightest talents are Alex Possebon to discover United’s Latino openly courted Arsenal’s Robin van Persie this busts while the jury is still out on the da Silva poised to keep shining in the summer. -

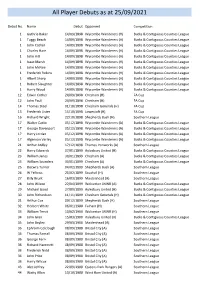

All Player Debuts As at 22/08/2021

All Player Debuts as at 25/09/2021 Debut No. Name Debut Opponent Competition 1 Guthrie Baker 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 Tuggy Beach 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 John Cother 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 Charles Hare 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 John Hill 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 Isaac Marsh 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 John McNee 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 Frederick Robins 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 Albert Sharp 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 Robert Slaughter 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 1 Harry Wood 14/09/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (H) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 12 Edwin Cother 24/09/1898 Chesham (H) FA Cup 12 John Paull 24/09/1898 Chesham (H) FA Cup 14 Thomas Steel 01/10/1898 Chesham Generals (H) FA Cup 15 Frederick Lister 15/10/1898 Lowestoft (H) FA Cup 16 Richard Wright 22/10/1898 Shepherds Bush (H) Southern League 17 Walter Catlin 05/12/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (A) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 17 George Davenport 05/12/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (A) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 17 Harry Jordan 05/12/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (A) Bucks & Contiguous Counties League 17 Algernon Varley 05/12/1898 Wycombe Wanderers (A) Bucks -

Twists in Store in Relegation Drama

Sports FRIDAY, JANUARY 16 , 2015 Saints march on as Spurs stage FA Cup comeback LONDON: Shane Long scored the winner as Premier But as the loose ball squirted away to the right of the Townsend’s cross was nodded on by Soldado and Paulinho League high-flyers Southampton saw off second-tier area, Republic of Ireland striker Long let fly with a first-time took the ball on his chest before unleashing a half-volley. Ipswich Town 1-0 in their FA Cup third-round replay on shot for what turned out to be the only goal of the game. Spurs equalised on the stroke of half-time through Wednesday. Victory saw the Saints, third in the Premier “It was a tough game,” Long told the BBC. “It was very Etienne Capoue before two goals early in the second half, League, book a fourth-round tie at home to top-flight rivals windy and the pitch was cut up. Ipswich are third in the from Vlad Chriches and Danny Rose, completed the come- Crystal Palace-a side now managed by former Championship for a reason and it was hard.” back. Afterwards, Pochettino said his side had been Southampton boss Alan Pardew. On the stroke of half-time, Southampton-already miss- involved in a “strange game”. “It was key to go in at half- Meanwhile Mauricio Pochettino, another ex- ing the influential Morgan Schneiderlin - saw Victor time at 2-2,” he added. “The team has shown character and Southampton manager, had a night to remember as his Wanyama suffer what appeared to be a hamstring injury. -

Topps Match Attax Premier League 2011/2012 EXTRA

www.soccercardindex.com 2011/2012 Topps Match Attax Extra English Premier League checklist Squad Updates New Signings Golden Goals U1 Carl Jenkinson - ARS N1 Thierry Henry - ARS GG1 Thierry Henry -ARS U2 Andre Santos - ARS N2 Robbie Keane - AST GG2 Stilyan Petrov - AST U3 Tomas Rosicky - ARS N3 Bradley Orr - BLA GG3 Alan Shearer - BLA U4 Alex Oxlade Chamerlaine - ARS N4 Tim Ream - BOL GG4 Nicolas Anelka - BOL U5 Francis Coquelin - ARS N6 Marvin Sordell - BOL GG5 Gustavo Poyet - CHE U6 Ju Young Park - ARS N5 Ryo Miyaichi - BOL GG6 Tim Howard - EVT U7 Marouane Chamakh - ARS N8 Darron Gibson - EVT GG7 Jon Harley - FUL U8 Carlos Cuellar - AST N9 Steven Pienaar - EVT GG8 Steven Gerrard - LIV U9 Barry Bannan - AST N7 Landon Donovan - EVT GG9 Georgi - MAC U10 Grant Hanley - BLA N10 Pavel Pogrebnyak - FUL GG10 Paul Scholes - MAU U11 Jason Lowe - BLA N11 David Pizarro - MAC GG11 David Ginola - NEW U12 Simon Vukcevic - BLA N13 Ryan Bennett - NOR GG12 Jeremy Goss - NOR U13 Joe Riley - BOL N12 Jonny Howson - NOR GG13 Ray Wilkins - QPR U14 Dedryck Boyata - BOL N16 Nedum Onuoha - QPR GG14 Ricardo Fuller - STO U15 Mark Davies - BOL N15 Taye Taiwo - QPR GG15 Niall Quinn - SUN U16 Ivan Klasnic - BOL N17 Samba Diakite - QPR GG16 Nathan Dyer - SWA U17 Jose Bosingwa - CHE N18 Djibril Cisse - QPR GG17 Danny Rose - TOT U18 Oriol Romeu - CHE N14 Fedrico Macheda - QPR GG18 Simon Cox - WBA U19 Daniel Sturridge - CHE N19 Wayne Bridge - SUN GG19 Maynor Figueroa - WIG U20 Denis Stracqualursi - EVT N20 Sotirios Kyrgiakos - SUN GG20 Alex Rae - WOL U21 Apostolos Vellios -

Kick-It-Out-Annual-Review

KICK IT OUT / ANNUAL REVIEW 2012–2013 It is said that a week is a long time in politics! The same can be said for the week-to-week lifelong struggles in confronting the debilitating effects of racism, discrimination, exclusion and inequality. Kick It Out, in its 20th year of leading such challenges in summit which led to the production of the Inclusion and the football world, experienced an eventful time with the Anti-Discrimination plan, co-ordinated by The FA on behalf fallout from the Terry and Suarez incidents in October 2011. of the football authorities. What can be said with certainty is that change rarely This demonstrated how purposeful protests pose occurs without the combination of confronting the challenges. Direct action across the whole of society to indefensible and yielding a positive response from the inequalities, injustices and unfair treatment, is the most powers that be. When those 30-plus players defied their effective way of challenging the status quo and must be clubs by not wearing the One Game, One Community done repeatedly to achieve the desired outcomes. weeks of action t-shirts in October 2012, they were rightly expressing their frustrations about the slow progress made When Kevin-Prince Boateng, fed up with being racially with eliminating racism from all parts of the game, in spite abused, walked off the field of play during a friendly of some notable improvements which have occurred during game, his AC Milan team-mates joined him as the the past two decades. referee and match officials failed to provide him with the protection necessary.