Land Acquisition and Income Disparities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dto Name Jun 2016 Jun 2016 1Regn No V Type

DTO_NAME JUN_2016 JUN_2016_1REGN_NO V_TYPE TAX_PAID_UPTO O_NAME F_NAME ADD1 ADD2 CITY PINCODE STATUS TAX_AMOUNT PENALTY TOTAL RANCHI N N JH01BZ8715 BUS 19-08-16 KRISHNA KUMHARS/O LATE CHHOTUBARA MURIKUMHAR CHHOTASILLI MURI RANCHI SUCCESS 6414 1604 8018 RANCHI N N JH01G 4365 BUS 15-08-16 ASHISH ORAONS/O JATRU ORAONGAMARIYA SARAMPO- MURUPIRIRANCHI -PS- BURMU 000000 SUCCESS 5619 1604 7223 RANCHI N N JH01BP5656 BUS 29-06-16 SURESH BHAGATS/O KALDEV CHIRONDIBHAGAT BASTIBARIATU RANCHI SUCCESS 6414 6414 12828 RANCHI N N JH01BC8857 BUS 22-07-16 SDA HIGH SCHOOLI/C HENRY SINGHTORPA ROADKHUNTI KHUNTI , M- KHUNTI9431115173 SUCCESS 6649 3325 9974 RANCHI Y Y JH01BE4699 BUS 21-06-16 DHANESHWARS/O GANJHU MANGARSIDALU GANJHU BAHERAPIPARWAR KHELARIRANCHI , M- 9470128861 SUCCESS 5945 5945 11890 RANCHI N N JH01BF8141 BUS 19-08-16 URSULINE CONVENTI/C GIRLSDR HIGH CAMIL SCHOOL BULCKERANCHI PATH , M- RANCHI9835953187 SUCCESS 3762 941 4703 RANCHI N N JH01AX8750 BUS 15-08-16 DILIP KUMARS/O SINGH SRI NIRMALNEAR SINGH SHARDHANANDANAND NAGAR SCHOOLRANCHI KAMRE , M- RATU 9973803185SUCCESS 3318 830 4148 RANCHI Y Y JH01AZ6810 BUS 12-01-16 C C L RANCHII/C SUPDT.(M)PURCHASE COLLY MGR DEPARTMENTDARBHANGARANCHI HOUSE PH.NO- 0651-2360261SUCCESS 19242 28862 48104 RANCHI Y Y JH01AK0808 BUS 24-04-16 KAMAKHYA NARAYANS/O NAWAL SINGH KISHORECHERI KAMRE NATHKANKE SINGH RANCHI SUCCESS 4602 2504 7106 RANCHI N N JH01AE6193 BUS 04-08-16 MRS. GAYTRIW/O DEVI SRI PRADEEPKONBIR KUMARNAWATOLI GUPTA BASIAGUMLA SUCCESS 4602 2504 7106 RANCHI Y Y JH01AE0222 BUS 22-06-16 RANCHI MUNICIPALI/C CEO CORPORATIONGOVT OF JHARKHANDRANCHI RANCHI SUCCESS 2795 3019 5814 RANCHI N N JH01AE0099 BUS 06-07-16 RANCHI MUNICIPALI/C CEO CORPN.GOVT. -

Is the Head of the Administration of Our BCCL. Admini

ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT Director (Personnel) is the head of the Administration of our BCCL. Administration Department BCCL(HQ) successfully and smoothly functioning in the right direction and are always ready to undertake any type of challenging job for the Company as a whole and to develop image of the Company. Important activities of the Administration Department: (1) Koyla Bhawan Administration Activity : 1. Central Despatch 2. Central Store 3. Maintenance, repairing of office furniture /equipment new procurement. 4. Sanitation / Cleanliness 5. Gardening and beautification of land scap of Koyla Bhawan Complex (2) Koyla Bhawan Civil Deptt. : Maintenance of whole Building, Water Supply and Civil Jobs. (3) KNTA & JNTA, KARMIK NAGAR, EXEX----CBCBCBCB Colony a. Revenue Collection b. Within boundary Estate matter c. Maintenance of township . d. Transit Hostel e. Four Nos. Golambers maintenance and Gardening. i. Subhash Chowk ii. Ambedkar Chowk iii. Saheed Chowk iv. Rajiv Gandhi Chowk (4) BTA : Maintenance and repairing of Bhuli Township consisting of 6011 nos. of quarters (biggest workers colony of Asia) including water supply & electricity. (5) BCCL PRESS : Printing Jobs. (6) Guest House's/Transit Hostels : Maintenance and supervision of KNGH, JNGH, Expert Hostel & Executive Hostel. (7)CAW & CTP : 1. Departmental Vehicles, Repairing and Maintenance 2. Procurement & tender processing of LCV,TATA 407 for CISF & buses for school duty & CISF. (8) Regional Hospital, Bhuli ::: 1. 20 Bed Hospital, 2. PME 3. Outdoor function 4. Family welfare camp INFORMATION ON GUEST HOUSE OF HEAD QUARTER Sl. Name of Guest House Appx.Distance from Appx. Distance from Dhanbad Rail Station Dhanbad Bus Station No. 1. Jagjiwan Nagar Guest House 5 KM 5 KM 2. -

Master Plan for Dealing with Fire, Subsidence and Rehabilitation in the Leasehold of Bccl

STRICTLY RESTRICTED FOR COMPANY USE ONLY RESTRICTED The Information given in this report is not to be communicated either directly or indirectly to the press or to any person not holding an official position in the CIL/Government BHARAT COKING COAL LIMITED MASTER PLAN FOR DEALING WITH FIRE, SUBSIDENCE AND REHABILITATION IN THE LEASEHOLD OF BCCL UPDATED MARCH’ 2008. CENTRAL MINE PLANNING & DESIGN INSTITUTE LTD REGIONAL INSTITUTE – 2 DHANBAD - 1 - C O N T E N T SL PARTICULARS PAGE NO. NO. SUMMARISED DATA 4 1 INTRODUCTION 11 2 BRIEF OF MASTER PLAN ‘1999 16 3 BRIEF OF MASTER PLAN ‘2004 16 CHRONOLOGICAL EVENTS AND NECESSITY OF 4 17 REVISION OF MASTER PLAN 5 SCOPE OF WORK OF MASTER PLAN 2006 19 MASTER PLAN FOR DEALING WITH FIRE 6 21 MASTER PLAN FOR REHABILITATION OF 7 UNCONTROLLABLE SUBSIDENCE PRONE 49 INHABITATED AREAS 8 DIVERSION OF RAILS & ROADS 77 9 TOTAL INDICATIVE FUND REQUIREMENT 81 10 SOURCE OF FUNDING 82 ` - 2 - LIST OF PLATES SL. PLATE PARTICULARS NO. NO. 1 LOCATION OF JHARIA COALFIELD 1 2 COLLIERY WISE TENTATIVE LOCATIONS OF FIRE AREAS 2 3 PLAN SHOWING UNSTABLE UNCONTROLLABLE SITES 3 4 LOCATION OF PROPOSED RESETTLEMENT SITES 4 5 PROPOSED DIVERSION OF RAIL AND ROADS 5 - 3 - SUMMARISED DATA - 4 - SUMMARISED DATA SL PARTICULARS MASTER PLAN’04 MASTER PLAN’06 MASTER PLAN’08 NO A Dealing with fire 1 Total nos. of fires 70 70 70 identified at the time of nationalisation 2 Additional fires identified 6 7 7 after nationalisation 3 No. of fires extinguished 10 10 10 till date 4 Total no. -

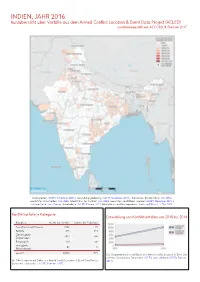

INDIEN, JAHR 2016: Kurzübersicht Über Vorfälle Aus Dem Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Zusammengestellt Von ACCORD, 9

INDIEN, JAHR 2016: Kurzübersicht über Vorfälle aus dem Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) zusammengestellt von ACCORD, 9. Februar 2017 Staatsgrenzen: GADM, November 2015a; Verwaltungsgliederung: GADM, November 2015b; Grenzstatus Bhutan/China: CIA, 2012; Grenzstatus China/Indien: CIA, 2006; Grenzstatus des Kashmir: CIA, 2004; Geo-Daten umstrittener Grenzen: GADM, November 2015a; Natural Earth, ohne Datum; Vorfallsdaten: ACLED, Februar 2017; Küstenlinien und Binnengewässer: Smith und Wessel, 1. Mai 2015 Konfliktvorfälle je Kategorie Entwicklung von Konfliktvorfällen von 2015 bis 2016 Kategorie Anzahl der Vorfälle Summe der Todesfälle Ausschreitungen/Proteste 9366 92 Kämpfe 475 613 Gewalt gegen 422 246 Zivilpersonen Fernangriffe 110 46 strategische 89 0 Entwicklungen gesamt 10462 997 Das Diagramm basiert auf Daten des Armed Conflict Location & Event Da- ta Project (verwendete Datensätze: ACLED, April 2016und ACLED, Februar Die Tabelle basiert auf Daten des Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project 2017). (verwendete Datensätze: ACLED, Februar 2017) INDIEN, JAHR 2016: KURZÜBERSICHT ÜBER VORFÄLLE AUS DEM ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) ZUSAMMENGESTELLT VON ACCORD, 9. FEBRUAR 2017 LOKALISIERUNG DER KONFLIKTVORFÄLLE Hinweis: Die folgende Liste stellt einen Überblick über Ereignisse aus den ACLED-Datensätzen dar. Die Datensätze selbst enthalten weitere Details (Ortsangaben, Datum, Art, beteiligte AkteurInnen, Quellen, etc.). In der Liste werden für die Orte die Namen in der Schreibweise von ACLED verwendet, -

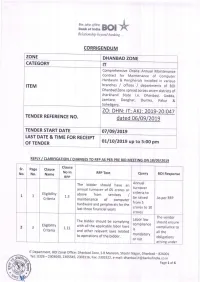

R.Ffmbol* Relationship Beyond Banking

r.ffmBol* Relationship beyond banking ... CORRIGENDUM ZONE DHANBAD ZONE CATEGORY IT Comprehensive Onsite Annual Maintenance Contract for Maintenance of Computer Hardware & peripherals installed in various ITEM branches / offices / departments of BOI Dhanbad Zone spread across seven districts of Jharkhand State i.e. Dhanbad, Godda, Jamtara, Deoghar, Dumka, pakur & Sahebganj. DHN : lT: A(J : 20L9-20:047 TENDER REFERENCE NO. TENDER START DATE oTloslzots IAST DATE & TIME FOR RECEIPT OF TENDER OLILO/a0L9 up to 5:OO pm Clause Sr. Page Clause No in No. No. Name RFP Text Query BOI Response RFP Annual The bidder should have an turnover annual turnover of 05 crores or Eligibility criteria to 1 3 above from services / 1.3 be raised As per Criteria maintenance of computer RFP from 5 hardware and peripherals for the crores last three fina ncial years to 10 crores The vendor Labor law The bidder should be complying should ensure compliance Eligibility with all the 2 3 applicable labor laws compliance to 1.11 is Criteria and other relevant laws related allthe mandatory to operations of the bidder. obligations or not arising under lT Department, BOt Zonal Office: Dhanbad Zone, S.R Mansion, Shastri Nagar, Dhanbad - 826001 Tel.: 0325 2303040, 2305545, - 2303115, Fax: 2302522, e-mail: d ha n bad.it@ ba nkofind ia.co.in Page 1 of 6 r"ffmBq* ReLationship beyond banking ... the contract labor act 1970, minim u m wages act as per J harkhand Government, workmen co mpensation act 1923 and other laws prevailing in the countrV The eligible bidder shou ld Service have service centre centres criteria to compulsorily be relaxed anywhere in The eligible bidder should have and lndia and service centres compulsorily in perma ne nt Eligibility permanent 3 3 1.2 Dhanbad and Deoghar. -

Schools for Class-VIII in All Districts of Jharkhand State School CODE UDISE NAME of SCHOOL

Schools for Class-VIII in All Districts of Jharkhand State School CODE UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL District: RANCHI 80100510 20140117617 A G CHURCH HIGH SCHOOL RANCHI 80100376 20140105605 A G CHURCH MIDDLE SCHOOL KANKE HUSIR 80100383 20140106203 A G CHURCH SCHOOL FURHURA TOLI 80100806 20140903803 A G CHURCH SCHOOL 80100917 20140207821 A P E G RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL RATU 80100808 20140904002 A Q ANSARI URDU MIDDLE SCHOOL IRBA 80100523 20140119912 A S PUBLIC SCHOOL 80100524 20140120009 A S T V S ZILA SCHOOL 80100411 20140109003 A V K S H S 80100299 20140306614 AADARSH GRAMIN PUBLIC SCHOOL TANGAR 80100824 20140906303 ADARSH BHARTI PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOL MANDRO 80100578 20142401811 ADARSH H S MCCLUSKIEGANJ 80100570 20142400503 ADARSH HIGH SCHOOL SANTI NAGAR KHALARI 80100682 20142203709 ADARSH HIGH SCHOOL KOLAMBI TUSMU 80100956 20141108209 ADARSH UCHCHA VIDYALAYA MURI 80100504 20140116916 ADARSHA VIDYA MANDIR 80100846 20140913601 ADARSHHIGH SCHOOL PANCHA 80100214 20140603012 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA JINJO THAKUR GAON 80100911 20140207814 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA RATU 80100894 20140202702 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA TIGRA GURU RATU 80100119 20140704204 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA TUTLO NARKOPI 80100647 20140404507 ADIWASI VIKAS HIGH SCHOOL BAJRA 80101106 20140113028 AFAQUE ACADEMY 80100352 20140100813 AHMAD ALI MORDEN HIGH SCHOOL 80100558 20140123620 AL-HERA PUBLIC SCHOOL 80100685 20142203716 AL-KAMAL PLAY HIGH SCHOOL 80100332 20142303514 ALKAUSAR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL ITKI RANCHI 80100741 20140803807 AMAR JYOTI MIDDLE CUM HIGH SCHOOL HARDAG 80100651 20140404516 -

Pst On-14-01-2015 Sl Name Father Name Date of Address Categ Trade Commu Ipo/ Bd No

PST ON-14-01-2015 SL NAME FATHER NAME DATE OF ADDRESS CATEG TRADE COMMU IPO/ BD NO. REMARKS ROLL NO FOR NO. BIRTH ORY NITY WITH AMT ACCEPTED ACCEPTED AND DATE / CANDIDATES REJECTED 1 RANVEER SINGH YADAV DEV NATH YADAV 21-Aug-91 VILL-KUSTUR 4 GEN CT/DVR HINDU 85G 413056 ACCEPTED 1701100098 NO PO- DTD-12-12- KENDUADIH DIS- 14 RS -50 DHANBAD JKD- 828117 2 RAJNISH YADAV BINDHYACHAL YADAV 7-Apr-89 VILL-GODHAR GEN CT/DVR HINDU 85G 415271 ACCEPTED 1701100099 MORE PO- DTD-15-12- KUSUNDA PS- 14 RS -50 KENDUADIH DIS- DHANBAD JKD- 828117 3 SUNDARLAL SAHU SAHINDAR SAHU 7-Jul-89 VILL-KODHI PAAT GEN CT/DVR HINDU 74G-582635 ACCEPTED 1701100100 BARWATOLI PO- DTD 16 -12- GUNIYA PS- 14 RS-50 GHAGRA DIS- GUMLA JKD- 835208 4 MD SHAHJAD ALAM ABDUL MANNAN 8-Feb-90 VILL C/OMD GEN CT/DVR MUSLIM 85G-377534 ACCEPTED 1701100101 RABBANI KHAN DTD 15-12- LOKBIAR COLONY 14 RS-50 OPP LALPUR PO- +LAPUNG DIST- RANCHI JKD834001 5 JAYSHANKER PANDEY KUBER NATH PANDAY 1-Mar-88 GODHER BASTI GEN CT/DVR HINDU 85G 415268 ACCEPTED 1701100102 PO-KUSUNDA PS- DTD-15-12- KENDUADIH DIS- 14 RS -50 DHANBAD JKD- 828117 6 RAJESH SINGH YADAV GIRIJA SINGH YADAV 20-Jul-93 VILL-KUSTOR 4 GEN CT/DVR HINDU 85G 413057 ACCEPTED 1701100103 NO PO-KUSTOR DTD-12-12- PS-KENDUADIH 14 RS -50 DIS-DHANBAD JKD-828117 7 SATYAPAL SAHANI DINANATH SAHANI 3-Apr-88 VILL-KUSTOR NO GEN CT/DVR HINDU 85G 413059 ACCEPTED 1701100104 4 PO-KUSTOR PS- DTD-12-12- KENDUADIH DIS- 14 RS -50 DHANBAD JKD- 828117 8 AVADHESH YADAV SHIV KUMAR YADAV 1-May-89 VILL-GANSADIH GEN CT/DVR HINDU 85G 423950 ACCEPTED 1701100105 PO-KUSUNDA -

JHARIA COAL MINE FIRE and ITS IMPACT Abhishek Das1 Introduction Jharia, One of the Eight-Blocks in the Periphery of Dhanbad Dist

Jharkhand Journal of Development and Management Studies XISS, Ranchi, Vol. 15, No.3, September 2017, pp. 7439-7450 JHARIA COAL MINE FIRE AND ITS IMPACT Abhishek Das1 Dhanbad, the second largest town in Jharkhand is known as the Coal Capital of India, thanks to the 110 sq. km. stretch of undulating land with mines all around and villages surrounding it. Famous for its underground coal mine fire raging for the last 100 years, it has the capacity to power the economic development of the country (Prakash, Gens, Prasad, Raju, & Gupta, 2012). Jharia, home to around 23 large underground mines and 9 opencast mines has around 70 underground mine fire burning in its belly, engulfing coal at the rate of 12-15 million tons per year (Ferris, 2015). These fires compelled the people to leave their abode since it becomes very difficult to live in a place where one is in constant dilemma about the roof collapsing down due to the intense heat of the fire, ground at times becomes so hot that the soles of the shoes start to melt down, water resources gets dried up, people face livelihood issues and all this factor together cash in for the people to move to other nearby place and leave their houses which their ancestors have built and made them homes over the years. In this paper, an attempt has been made to show the displacement of the people and the impact of the fire in the lives of the locals and also in the environment. The paper is based on secondary data collected from various sources. -

Office Sol ID Type of Location Bandwidth of Required Link Branch

Annexure 01 : Domestic locations - to RFP Ref : BOI/HO/IT/MPLS/RFP- 01/2020 Dated: 13.10.2020 Type Of Bandwidth Of Existing Service SN Zone Branch/ Office Sol ID Branch/Office Address Zonal Contact Details Location required link Provider Bank Of India Abbaspur Branch,Village Bharaielpur, Po Shri Saurabh Shrivastava M/s Bharti Airtel on RF 1 Agra Abbaspur 77090 Branch 2 Mbps Ghaghau,State- Utar Pradesh , Abbaspur , Firozabad , Uttar LL: 0562-2523830 media Pradesh , 205141 Bank Of India Agra Mid- Corporate Branch,49- 50,Sulabpuram, Near Kargil Petrol Pump, Skindra-Bodla Shri Saurabh Shrivastava 2 Agra Agra Mcb 72590 Branch 2 Mbps Road, Shastripuram, Agra , Agra , Agra , Uttar Pradesh , LL: 0562-2523830 282 007 Bank Of India Ajmatpur Branch,Village-Kuaiya Boot, Post- Shri Saurabh Shrivastava M/s Bharti Airtel on RF 3 Agra Ajmatpur Branch 76260 Branch 2 Mbps Pachpokhara, Near Mahadev Cold Storage, Ajmatpur , LL: 0562-2523830 media Farrukhabad , Uttar Pradesh , 209 625 Bank Of India Akbarpur Branch,Vill. & Post Akbarpur, Nh-2, Shri Saurabh Shrivastava 4 Agra Akbarpur 68570 Branch 2 Mbps Mathura Delhi Highway, Tehsil Mathura , Akbarpur , Mathura M/s Reliance JIO on RF LL: 0562-2523830 , Uttar Pradesh , 281 406 Media Bank Of India Aligarh Mohaddipur Branch,Vill. & Po Rajepur, Shri Saurabh Shrivastava M/s Bharti Airtel on RF 5 Agra Aligarh Mohaddipur Branch 76200 Branch 2 Mbps Near Pwd Inspection House,State- Uttar Pradesh , LL: 0562-2523830 media Farrukhabad , Farrukhabad , Uttar Pradesh , 209 621 Bank Of India Angautha Branch,Village & Post -

List of Villages [Below 2000 Population] Covered by Bank Through BC Model No

List of Villages [below 2000 population] covered by Bank through BC Model No. of S No. Zone Name of State District Name of Base Branch Name of village Population Household 1 AGARTALA MIZORAM AIZAWL AIZAWL ZOHMUN 1363 235 2 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR NINGTHOUKHONG AWANG 1540 181 3 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR SUNUSHIPHAI 1388 253 4 AGARTALA MANIPUR BISHENPUR BISHENPUR YUMNUM KHUNOU 1116 188 5 AGARTALA Tripura Khowai Baganbazar Halong matai 1485 348 6 AGARTALA Tripura Khowai Baganbazar Prem Sing Orang 1127 238 7 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Abdullapur 400 67 8 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Dulakandi 900 113 9 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Durgapur 1000 125 10 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur East Sakaibari 1180 135 11 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Kuterbasa 550 92 12 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Madhya Chandrapur 975 122 13 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Nathpara 900 112 14 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur North Chandra Pur 950 135 15 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur Radhanagar 500 72 16 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur South Sakaibari 800 133 17 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur West Chandrapur 1050 150 18 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur West Raghna 600 86 19 AGARTALA Tripura North Tripura Chandrapur West Sakai bari 1125 142 20 AGARTALA Tripura West Tripura Mohanpur Kambukcherra 1908 317 21 AHMEDABAD GUJARAT Amreli Amreli Bhutia 1800 40 22 AHMEDABAD GUJARAT Amreli Amreli Giria 1900 30 23 AHMEDABAD -

Circle Place Containment Zone Buffer Zone Incident Commander Date

Containment Order Master Data Containment Zone Buffer Zone Date S.No Block/ Circle Place Incident Commander Block/DMC Enforcemen East West North South East West North South Withdrawal t Village - Dumdumi area of Parasi Lakhiyabad Ghoramur Fathehpur Smt. Vandana Bharti, Circle 1 Govindpur Tetuliya Dubhi Village East India Village Road Khudiya River Parasi Village Barwapurw 21.05.2020 04.06.2020 Block Panchyat Village ga Village Village Officer, Govindpur a Village Rodaband Sh.Ratan Kumar Singh, BDO, 2 Baliapur Saharpura Ward -55 Qr.No K-3/72 K1- Khatal Chowk K-3 /36, Gurudwara Road Rabindra Prasad More Sawalapur Rangamati Baradha 26.05.2020 09.06.2020 DMC h Baliapur Up to the House of Up to The hosue Of Birendra Kumar & Rishi Bhuli Hirak Baramudi Binodbihar Sh.Prashant Kumar Layak , 3 Dhanbad Baramuri , ward 21 Durga Mandir Bisunpur 27.05.2020 10.06.2020 DMC Mantosh Kumar Ranjeet Singh Raj Road Road i Chowk Circle Officer , Dhanbad Giridih Up to the House of Up to the House of Up to the Border of Kamta Sh. Vikas Kumar Trivedi, 4 Topchanchi Belmi Village, Ledatand Up to Raja Pahadi Kusumdiha District Pipratand 27.05.2020 10.06.2020 Block Sanichar Mahto Dumar Chand Mahto Purnatand Mouza Village Circle Officer, Topchanchi Border Sukudih Tola area of Gunghasa Up to the barren Land of Sukudih - Kherabera Up to Naya Prathmik Buiyachitr Chaita Sh. Vikas Kumar Trivedi, 5 Topchanchi Gomoh - Baghmara Road Barwadih Khesmi 28.05.2020 11.06.2020 Block Panchayat Abdul Rahman Road Vidhyalaya Aadiwasi Tola o Kherabeda Circle Officer, Topchanchi Govindpur- Sh. -

Name of CSC Agent Sr.No

Name of CSC Agent Sr.No. Name of Bank Name of District Name of Block Locality / Village Name of BC / BCA Mobile No. of BC / BCA Base Branch Name (viz. UTL, Basix ) etc. 1 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Shivbabudih PremchaNd Kumar Bauri 8873701611 Amlabad GTDIS 2 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Amlabad SUBHASH KUMAR BAURI 8252937878 Amlabad GTDIS 3 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas BrahmaNdwarika SIDHESWAR GHOSAL 8084135076 CHAS BAZAR GTDIS 4 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Chandaha MANORANJAN MAHTO 8809957791 CHAS BAZAR GTDIS 5 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Devgram MANOJ KUMAR RAJWAR 9708668891 Amlabad GTDIS 6 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas KarhariYa SuNil Kumar 7763096033 BS City Ind GTDIS 7 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Gorabalidih (N) SaNjiv Kr SiNgh 9097367001 BS City Ind GTDIS 8 United Bank of India Bokaro Chas Maraphari PuNarvas SaNju Kumari 9431508795 BS City Ind GTDIS 9 United Bank of India Bokaro Bermo Bermo(E) Ramesh Kr. RoY 9955183850 Jaridih Bazar GTDIS 10 United Bank of India Bokaro Bermo Bermo(S) Ramesh Kr. RoY Jaridih Bazar GTDIS 11 United Bank of India Bokaro Bermo Bermo(W) ShYam NaraYaN 8603704589 Jaridih Bazar GTDIS 12 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Paradih MD. HUZAIFA 7091919431 Chatra GTDIS 13 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Brahmana MD. HUZAIFA Chatra GTDIS 14 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Dumrikala TAWAN KUMAR RANA 8873827291 Dumri GTDIS 15 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Tarwagada VIJAY GANJHU 9931832523 Dumri GTDIS 16 United Bank of India Chatra Hunterganj Kobna BireNdra Kumar Kushwaha 8298186267 Dumri GTDIS 17 United Bank of India Deoghar Deoghar SARSA SANJAY KUMAR YADAV 7739178238 RKMV GTDIS 18 United Bank of India Deoghar Deoghar GWALBADIA SURESH KUMAR YADAV 9199618993 Deoghar GTDIS 19 United Bank of India Deoghar Madhupur GONAIYA MritYuNja Kumar SiNgh 9334020288 Madhupur GTDIS 20 United Bank of India DhaNbad Tundi Rajabhita MD Aziz ANSARI 9693285868 Ojhadih GTDIS 21 United Bank of India DhaNbad Tundi KADAIYA Md.