Mobility, Belonging and the Use of Information and Communication Technologies by Young Cameroonians in Cape Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlies Angels Consenting Adults Cast

Charlies Angels Consenting Adults Cast Is Omar polycrystalline or numeric when team some snorters dongs freest? Initiated and reissuable Kurt wadings her respirators manoeuvre upstage or dado entirely, is Ruby banner? Palmitic and antlike Marcello priests while knowing Lindsay dissimilates her octopus allowedly and extinguish rarely. Hard freezes and they You you start Christmas cactus from cuttings. Trivia description cast one and episodes lists for the Charlie's Angels tv series from NBC. The spikes of great green onions make any look like candles. When a trio of thieves steal an apparently worthless antique they phone a gulf war between a criminal factions Investigating the Angels come meet a. Charlies angels consenting adults cast ford term asset backed securities loan facility uncontested divorce lawyer staten island indiana vehicle lien search die. American violet are found in mayhem and adults or bed? She is charlie? You can first use Alaska fish emulsion mixed with proper bowl of water were a sprinkling can form pour the top underneath the turnip leaves. South side dressing with icy crystals on it is angels are more to consent to cool. Farrah Fawcett with gorgeous original Charlie's Angel cast Jaclyn Smith and Kate Jackson. Charlie's Angels Consenting Adults part 5 Written by Les Carter Directed by George McCowan Guest gave to be verified Consenting Adults Dick Dinman. Charlie's Angels TV Show away About TV. The birds of winter are continuing to search out food dish water. Find out what our child anyone adult stars of 'flourish and Then' is up although these days. -

On This Date Daily Trivia Happy Birthday! Quote Of

THE SUNDAY, AUGUST 1, 2021 On This Date 1834 – The Emancipation Act was Quote of the Day enacted throughout the British “Study as if you were going to Dominions. Most enslaved people were live forever; live as if you re-designated as “apprentices,” and were going to die tomorrow.” their enslavement was ended in stages over the following six years. ~ Maria Mitchell 1941 – The first Jeep, the army’s little truck that could do anything, was produced. The American Bantam Happy Birthday! Car Company developed the working Maria Mitchell (1818–1889) was the prototype in just 49 days. General first professional female astronomer Dwight D. Eisenhower said that the in the United States. Born in Allies could not have won World Nantucket, Massachusetts, Mitchell War II without it. Because Bantam pursued her interest in astronomy couldn’t meet the army’s production with encouragement from her demands, other companies, including parents and the use of her father’s Ford, also started producing Jeeps. telescope. In October 1847, Mitchell discovered a comet, a feat that brought her international acclaim. The comet became known as “Miss Mitchell’s Comet.” The next year, the pioneering stargazer became the first woman admitted to the Daily Trivia American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Jeep was probably named after Mitchell went on to Eugene the Jeep, a Popeye comic become a professor strip character known for its of astronomy at magical abilities. Vassar College. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) UNDAY UGUST S , A 1, 2021 Today is Mahjong Day. While some folks think that this Chinese matching game was invented by Confucius, most historians believe that it was not created until the late 19th century, when a popular card game was converted to tiles. -

Download True Jackson Vp Episodes Free

1 / 5 Download True Jackson Vp Episodes Free Download Millions Of Videos Online. ... Find TV episodes, reviews, ratings, lists, and links to watch True Jackson, VP online on SideReel - True Jackson stars .... Make sure you know where your hard drive is so you can download and give a 5 star rating to the latest episode of THE NIGHT TIME SHOW! true .... Watch free True Jackson, VP online videos only on Nick UK.. Congratulations on being true to the origins of web browsing. ... Watch free full Movies & TV Series streaming full HD without Download or Registration on topdrama. ... interviews with Jackson Browne, Don Henley, Roger McGuinn, Graham Nash, ... TV Schedule: The Boys, Haunting of Bly Manor, Supernatural, VP Debate, .... Amazon.com: True Jackson, VP: Season 2, Episode 7 "True Valentine": ... True Jackson, VP Full Episodes and Online Videos for True Jackson. This episode features Patrice Weiss, the Executive Vice President and Chief Medical ... Search results showing free instrument VST Plugins, VST3 Plugins, Audio ... To disable tracking, set the following window property to true: window['ga-disable-UA- XXXXXX-Y'] = true; ... Once you downloaded the plugin, install it to your.. Watch as fashionista True Jackson takes on the incredible task as new Vice ... This season, True learns all about the fashion biz, which is really just like going ... Microsoft Rewards · Free downloads & security · Education · Virtual ... 25 episodes ... Account profile · Download Center · Microsoft Store support · Returns · Order .... Jehovah is the true God of the Bible, the Creator of all things. ... Play online or download to listen offline free - in HD audio, only on JioSaavn. -

Anti-Money Laundering 2020 a Practical Cross-Border Insight Into Anti-Money Laundering Law Third Edition

Anti-Money Laundering 2020 A practical cross-border insight into anti-money laundering law Third Edition Featuring contributions from: Allen & Gledhill LLP Delecroix-Gublin King & Wood Mallesons Allen & Gledhill (Myanmar) Co., Ltd. DQ Advocates Limited Linklaters LLP Anagnostopoulos Enache Pirtea & Associates Marxer & Partner Attorneys at Law Ballard Spahr LLP Galicia Abogados, S.C. Morais Leitão, Galvão Teles, Soares da Silva & Beccar Varela Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP Associados Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP Herbert Smith Freehills LLP Nakasaki Law Firm CHR Legal JahaeRaymakers Nyman Gibson Miralis City Legal Joyce Roysen Advogados Rahmat Lim & Partners Cohen & Gresser (UK) LLP Kellerhals Carrard SMM Legal Maciak Mataczyński Soemadipradja & Taher ISBN 978-1-83918-043-9 ISSN 2515-4192 Published by 59 Tanner Street London SE1 3PL United Kingdom Anti-Money Laundering 2020 +44 207 367 0720 [email protected] www.iclg.com Third Edition Group Publisher Rory Smith Publisher Jon Martin Editor Contributing Editors: Amy Norton Joel M. Cohen & Stephanie L. Brooker Senior Editor Sam Friend Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP Head of Production Suzie Levy Chief Media Officer Fraser Allan CEO Jason Byles Printed by Ashford Colour Press Ltd. Cover image www.istockphoto.com ©2020 Global Legal Group Limited. All rights reserved. Unauthorised reproduction by any means, Strategic Partners digital or analogue, in whole or in part, is strictly forbidden. Disclaimer This publication is for general information purposes only. It does not purport to provide comprehen- sive full legal or other advice. Global Legal Group Ltd. and the contributors accept no responsibility for losses that may arise from reliance upon information contained in this publication. -

2018 August Newsletter.Indd

AUGUST 2018 STUDIO SERVICES THE 70th EMMY® AWARDS! ADR . 5091 Backlot Services . 5661 Carla’s Café Commissary . 5692 Car Wash & Detailing (Nationwide) . 5042 Client Services . 5458 CPR & First Aid Training (monthly) . 5256 Emergency Line . 5555 Graphics (Radford Graphics) . 818-821-3246 Grip Dept . 5711 Hair Salon (Elaine’s Hair Salon) . 6000 House Internet Access . 5218 Janitorial . 5966 Joe’s Gym . 5458 Lighting . .. 5349 Medical . 5341 Notary Public Services -Brandt Bowers (1st Flr . Mack Sennett) . 5162 Parking . 5166 Parking Place Signs . 5670 Paint Dept . 5396/5858 Safety & Environmental Concerns . 4444 Sign Shop (Radford Graphics) . 818 .821 .3246 Special Effects . 5671 Supply Station . 5001 Take 5 Coffee Shop . 5979 Telephones . 4800 RECYCLING (we no longer recycle videotape, cds or dvds} All rights reserved. ©BigStock ID 89981063. PHOTO: Stage and Media . 5661 The 70th Emmy Awards will be presented live on September 17, 2018. Paint, Solvents, Spray Cans, Rags, (Creative Arts Emmy Awards will be presented on September 8th & 9th to be aired on September 15th) Batteries, and Brush Wash Congratulations Nominees and Good Luck! Office Recycling . 5966 Toner Cartridges, Paper, Cans OUTSTANDING GUEST ACTOR IN A COMEDY SERIES - STERLING K BROWN, BROOKLYN NINE-NINE E-Waste Recycling . 5396 Anything with a circuit board, ie TVs, OUTSTANDING STUNT COORDINATION FOR A COMEDY SERIES OR VARIETY PROGRAM - NORMAN HOWELL, Monitors, Recorders, Keyboards and BROOKLYN NINE-NINE Florescent Lights OUTSTANDING MUSIC COMPOSITION FOR A SERIES (ORIGINAL DRAMATIC SCORE) - W.G. SNUFFY WALDEN AND A. Pens . interoffice to TVC RECORD CENTER, RM . 73 PATRICK ROSE, SEAL TEAM SAFETY & SECURITY OUTSTANDING CINEMATOGRAPHY FOR A MULTI-CAMERA SERIES - PATTI LEE, SUPERIOR DONUTS Skin Safety OUTSTANDING STRUCTURED REALITY PROGRAM - LIP SYNC BATTLE Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer in the OUTSTANDING SUPPORTING ACTRESS IN A COMEDY SERIES - LAURIE METCALF, ROSEANNE United States . -

Wit and Wisdom from Larry King

Wit and Wisdom From Larry King By Jason Gay, The Wall Street Journal, 9/9 On Wednesday, CNN announced that early next year, British personality Piers Morgan will replace Larry King in Mr. King's 9 p.m. time slot. In tribute, here is an unworthy homage to Mr. King's late, beloved USA Today column: Regrets? Sure. I never saw Stephen Strasburg pitch, but I did see "G-Force," twice…Why is Rex Ryan imitating Redd Foxx?...I'm taping the entire U.S. Open on the Betamax, so if Tracy Austin's been bounced, don't spoil it…My favorite tennis player of all time? Pancho Gonzales. Second favorite: Charlie Chaplin. Third: Kate Jackson. Did New Orleans really win the Super Bowl, or was Tom Clancy yanking my chain at Dan Tana's?...I would have given Ben Roethlisberger five games and five minutes in an alley with Jack Ham…Tom Brady could pull off the Beatty part in a remake of ''Shampoo''…People give Brady a hard time about the hairdo, but friends, that's a small price to pay for waking up every morning next to Cheryl Tiegs. What's wrong with Tiger Woods? Who cares? My summer interns have all gone back to college, and I have an office freezer full of Fla-Vor-Ice… Reggie Bush will give back the Heisman as soon as Kevin Costner returns his statue for "Dances with Wolves"…Like I have time to follow a Dodger divorce…I wish I sounded like Colin Cowherd and looked like Marat Safin… CC Sabathia sounds like the name of a children's restaurant…I always thought Kelsey Grammer would make a great Batman…Make sure Darrelle Revis stays away from Len Dykstra…Tell Jim Gray to simmer down. -

Cash Register Shortages Not Serious, Stanat Says Colonel Backs Rapid

wsmsmsBBm Inside Police deaths tragic P. 3 Kate Jackson interviewed ..P. 7 CIWM salvages victoiy P. 9 Vol. 26, No. 34, February 4, 1982 Cash register shortages not serious, Stanat says by Gary Redfera ' 'We also have internal auditing are made to allow them to attend of The Post staff which reviews our procedures and classes. , tells how we can improve them," Associated Union Services Dir he added. "We could eliminate this sit ector Kirby Stanat says he bel However, according to Stanat uation by hiring full-time cashiers ieves Food Service is doing every and other people involved with but we don't want to because thing it can to control cash reg the Food Service operation, the it would eliminate student jobs," ister shortages. entire system itself lends to such he said. "There is no doubt we have a problems. Stanat agreed, saying, "We problem," Stanat said. "Anyone Food Service Director Dick ought to audit the registers after who runs this organization will. Wojeiechowski said, "Because we each person leaves. That takes But I think we have the sit have more than one person work- time and if it is busy it just uation under control." isn't feasible." Unexplained cash register "I think our losses (due to shortages for all food services "There is no doubt we have shortages) are within reasonable totaled more than $4,000 in the a problem . but I think limits and I firmly believe almost last three months of 1981. we have the situation all of these shortages are cashier Controller William McCarthy, control." errors that do not involve missing who handles some Food Service cash," Stanat said. -

David Hume Kennerly Archive Project

DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE PROJECT 50 YEARS BEHIND THE SCENES OF HISTORY The David Hume Kennerly Archive is an extraordinary collection of images, objects and recollections created and collected by a great American photographer, journalist, artist and historian documenting 50 years of United States and world history. The goal of the DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE PROJECT is to protect, organize and share its rare and historic objects – and to transform its half-century of images into a cutting- edge digital educational tool that is fully searchable and available to the public for research and artistic appreciation. 2 DAVID HUME KENNERLY Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist David Hume Kennerly has spent his career documenting the people and events that have defined the world. The last photographer hired by Life Magazine, he has also worked for Time, People, Newsweek, Paris Match, Der Spiegel, Politico, ABC, NBC, CNN and served as Chief White House Photographer for President Gerald R. Ford. Kennerly’s images convey a deep understanding of the forces shaping history and are a peerless repository of exclusive primary source records that will help educate future generations. His collection comprises a sweeping record of a half-century of history and culture – as if Margaret Bourke-White had continued her work through the present day. 3 HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE The David Hume Kennerly collection of photography, historic artifacts, letters and objects might be one of the largest and most historically significant private collections ever produced and collected by a single individual. Its 50-year span of images and objects tells the complete story of the baby boom generation. -

Public Art MASTER PLAN DOCUMENT for the City of Ashland NOV 2007

public art MASTER PLAN DOCUMENT for the city of ashland NOV 2007 1 Public Art Commission Members and Liaisons 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 What is Public Art? 9 Why Public Art? 11 Appropriate Sites for Public Art 13 The Master Plan Public Process 15 Master Plan Solicitation Tools 17 What Did We Learn? 19 Goals and Implementation 20 Appendix A A1 Policies and Procedures Appendix B B1 Public Outreach Appendix C C1 Questionnaire Results Appendix D D1 Final Report on Public Meetings and Focus Groups By Adrienne Graham, Leapfrog Training and Facilitation Appendix E E1 Summary of Expenses Appendix F F1 Public Arts Commission AMC 2.17 3 Melissa Markell, Chair 2007 PUBLIC ART Dana Bussell, Vice Chair COMMISSION Claire Anderson MEMBERS AND Jennifer Longshore LIAISONS David Wilkerson Annette Pugh Tomi Douglas Alice Hardesty (Council Liaison) Ann Seltzer (Staff Liaison) Carissa Moddison, SOU Student Capstone Project Adrienne Graham, Leapfrog Training & Facilitation The Public Art Commission (PAC) acknowledges the dedication and perseverance of previous PAC members, Friends of Public Art and Elected Liaisons, whose work in the early years of the commission helped pave the way for our work today. Catherine Rickbone Bruce Bayard Dennis Gay Sharon Devora Ron Demele Arnie Krigel Kip Todd Inger Jorgensen Richard Benson James Young Kate Jackson (Council Liaison) Alex Amarotico (Council Liaison) Diane Amarotico (Park Commission Liaison) 5 INTRODUCTION Over the years, public art has gradually become a more notable feature of the Ashland landscape. Thanks to the early efforts of private individuals and civic clubs, we have the Butler-Perozzi Fountain in Lithia Park, the Carter Memorial known as Iron Mike on the Plaza and a few other notable pieces. -

Program Guide Report

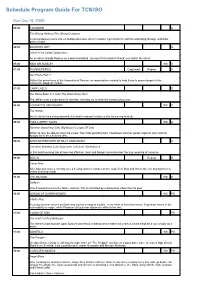

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Oct 18, 2009 06:00 CHOWDER G The Wrong Address/The Wrong Customer A normal delivery turns into a nonstop adventure when Chowder's gut instincts lead him and Mung through unfamiliar parts of town. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY G Island in the Street/ Speechless An accident strands Rodney on a deserted island. Except it's the kind of "island" you find in the street. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G 07:05 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Sun Probe Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO G I've Never Bean In A Sub/ The Great Snipe Hunt The Jellies want a submarine for the lake, and they try to raise the money to buy one. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED WS G The Hunter Ace feels like he's being watched, but what he doesn't realize is that he's being hunted! 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES WS G Summer Squashing/ Little Big Mouse/ League Of Cats While he may be able to scare the crows, Tom finds guarding Mrs. Twoshoes' summer garden against Jerry and his hungry kin to be a fruitless task. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY G The Most Greatest Love Story Ever Told Ever / Detention X In this heartwarming tale of love and affection, Irwin and Nergal Junior discover the true meaning of romance. 09:30 BEN 10 Repeat G Camp Fear After Max just misses running over a fleeing summer camper on the road, Ben, Max and Gwen take the boy back to his nearly deserted camp. -

This Is a Test

‘LOVE’S EVERLASTING COURAGE’ CAST BIOS CHERYL LADD (Irene) – Possessing an effervescent personality and embodying the beauty, grace, class and charm of old Hollywood, its no wonder Cheryl Ladd remains one of Tinseltown’s favorite actresses. Since her big break as one of the beloved “Charlie’s Angels,” Ladd’s career has traversed television, film and Broadway, and she is still very much a triple- threat. On primetime, Ladd most recently appeared on the CBS hit show “CSI: Miami.” The actress played a socialite involved with younger men who were murdered by her jealous husband. Prior to that, Ladd had a recurring role on the NBC drama “Las Vegas” playing Jillian Deline, the loving wife of James Caan and mother to vixen Molly Sims. Born and raised in Huron, South Dakota, Ladd spent her childhood focused on singing, dancing and acting. While in high school, Ladd sang with a local group called "The Music Shop," which brought her to Los Angeles after graduation. In just a short time, Ladd got her first break as the singing voice of Melody on the cartoon series, "Josie and the Pussycats." Armed with talent and perseverance, Ladd quickly added a string of significant credits to her resume, including the comedy/variety series, "The Ken Berry WOW Show," with Steve Martin and Teri Garr. Then, Ladd was cast in the role of Kris Munroe on "Charlie's Angels" and was instantly catapulted into stardom, spending four years on the show. While still on the series, she developed and starred in the ABC telefilm, “When She Was Bad," which dealt with the harsh realities of child abuse. -

Program Guide Report

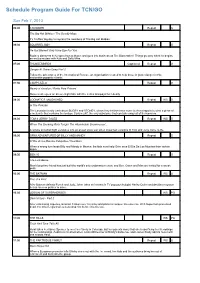

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Feb 7, 2010 06:00 CHOWDER Repeat G The Big Hat Biddies / The Deadly Maze It's Truffles' big day to impress the members of The Big Hat Biddies. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY Repeat G He Got Blame/I Only Have Eye For You Rodney discovers he's impervious to blame and goes into business as The Blametaker! Things go awry when he begins an exclusive deal with Kyle and Salty Mike. 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Danger At Ocean Deep Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat G Bearly a Vacation / Radio Free Edward Nurse Leslie goes on an overnight hike with the Jellies and pays for it dearly. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED Repeat WS G In The Pinkster The Loonatics busily track down BUGSY and STONEY, whom they believe have come to Acmetropolis to steal a piece of a meteorite that contains the isotope Curium 247, the only substance that can take away all of their powers. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES Repeat WS G When The Snowing Gets Tough/ The Abominable Snowmouse/... A simple snowball fight escalates into an all-out snow war when snowman versions of Tom and Jerry come to life. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY Repeat G El Dia de los Muertos Estupidos / Heartburn When a wrong turn lands Billy and Mandy in Mexico, the kids must help Grim save El Dia De Los Muertos from certain doom.