The Bulletin Number 78 Spring 1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petroglyphs of Pennsylvania Pennsylvania of Petroglyphs

12/07 by Larry A. Smail. A. Larry by Petroglyphs Landing Parker’s is painting cover The www.phmc.state.pa.us/bhp/ • Washington, D.C. 20240 D.C. Washington, www.PaArchaeology.state.pa.us • 1849 C Street, N.W. Street, C 1849 www.pennsylvaniaarchaeology.com • National Park Service Park National Office of Equal Opportunity Equal of Office obtained at: obtained desire further information, please write to: write please information, further desire recording forms, and instructions can be be can instructions and forms, recording discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you you if or above, described as facility or activity, program, any in against discriminated origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been been have you believe you If programs. assisted federally its in age or disability, origin, Archaeological Site Survey (PASS). Information, Information, (PASS). Survey Site Archaeological Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national national color, race, of basis the on discrimination prohibits Interior the of Department record these locations with the Pennsylvania Pennsylvania the with locations these record Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. U.S. the amended, as 1975, of Act Discrimination Age the and 1973, of Act Rehabilitation of archaeological sites, we encourage you to to you encourage we sites, archaeological of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the the of 504 Section 1964, of Act Rights Civil the of VI Title Under properties. -

Project Archaeology: Pennsylvania

PROJECT ARCHAEOLOGY: PENNSYLVANIA AN EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS BASED CURRICULUM FOR GRADES FOUR THROUGH EIGHT STUDENT TEXT (FOR USE WITH LESSON PLAN BOOK) AN EDUCATIONAL INITIATIVE OF THE PENNSYLVANIA ARCHAEOLOGICAL COUNCIL EDUCATION COMMITTEE THIS PROJECT IS SUPPORTED BY A GRANT FROM THE PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL AND MUSEUM COMMISSION PROJECT ARCHAEOLOGY: PENNSYLVANIA AN EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS BASED CURRICULUM FOR GRADES FOUR THROUGH EIGHT STUDENT TEXT (FOR USE WITH LESSON PLAN BOOK) Project Directed and Edited by Renata B. Wolynec, Ph. D. Contributing Authors: Renata B. Wolynec, Ph. D. Ellen Dailey Bedell, Ph. D. Edinboro University of PA Ellis School, Pittsburgh Sarah Ward Neusius, Ph. D. Beverly Mitchum Chiarulli, Ph. D. Indiana University of PA Indiana University of PA Joseph Baker PA Department of Transportation, Harrisburg SECTION ONE – BASIC CONCEPTS Chapter 1 -- What Is Anthropology? (Wolynec) Chapter 2 -- What Is Archaeology? (Wolynec) Chapter 3 -- Meet an Archaeologist (Wolynec, Bedell, Neusius, Baker, and Chiarulli) Chapter 4 -- How Do Archaeologists Do Their Work? (Wolynec) Chapter 5 -- How Old Is It? (Wolynec) SECTION TWO – PENNSYLVANIA BEFORE THE EUROPEANS Chapter 6 -- History and Culture in Pennsylvania Place Names (Wolynec) Chapter 7 -- What Was Pennsylvania Like Before European Contact? (Neusius) Chapter 8 -- Where Did the Ancestors of Native Americans Come From? (Wolynec) Chapter 9 -- Native American History in Pennsylvania Before the Europeans (Wolynec) SECTION THREE - COMPARING CULTURES Chapter 10 -- What Basic Needs Do -

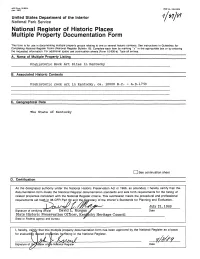

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

(Jan.,N,PS ^V°-900-bI9o7) ' .-. 0MB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing _______Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in Kentucky________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ ___ Prehistoric rock art in Kentucky, ca. 10000 B.C. - A.D.17 50 C. Geographical Data I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set foittnn 36 CFR Part 60 and the^ejjretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. July 21, 1989 Signature of certifying official David L. Morgan ^^ Date State Historic Preservation Officer, Kerdrocky Heritage Council___________ State or Federal agency and bureau ' I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluatirjfg related proj$)erties fcyfisting in the National Register. ^S*£* fj' /] / v^^r" 7 V l^W" - " ~ ' Signature of tb^Keeper of/Me National Register Date E. -

Oil Heritage Region Management Plan Augmentation Environmental Assessment

Oil Heritage Region Management Plan Augmentation Environmental Assessment Prepared for the Oil Region Alliance of Business, Industry, and Tourism July 12 , 2006 prepared by ICON architecture, inc. in association with Vanasse, Hangen, Brustlin, Inc. Oil Region National Heritage Area Plan Augmentation - 7/12/06 Grant Acknowledgement This project was funded, in part, by the United States Department of the Interior through the National Park Service by a grant to the Oil Region Alliance of Business, Industry & Tourism. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. Credits This document was prepared by ICON architecture, inc., in association with VHB, Inc. for the Oil Region Alliance of Business, Industry and Tourism (the “Alliance”). The consultants wish to acknowledge the substantial assistance and input provided by the ORA Board of the Alliance as well as by the Heritage Advisory Council. Members of these groups included: Oil Region Alliance of Business, Industry, and Tourism Board Officers and Executive Committee: Chair: Jonathan D. "Jack" Crawford; President, Kapp Alloy & Wire, Inc. (2005-2006) Vice-Chair: James Hawkins; President, Barr's Insurance (2005-2006) Secretary: Debra Sobina; Director of Finance and Administration, Clarion University (2005); Lynda Cochran (2006) Treasurer: Neil McElwee; Owner, Oil Creek Press (2005-2006) Assistant Secretary-Treasurer: Lynda Cochran; Executive Director, Titusville Chamber of Commerce (2005), Betsy Kellner, Executive Director, Venango Museum of Art, Science & Industry (2006) Executive Committee Members: Dennis Beggs; Director of Finance and Administration, Central Electric Cooperative (2005-2006) Susan Smith; Chair, County Commissioners, County of Venango (2005-2006) Members of the Board of Directors: Janet Aaron, Owner, Alturnamats, Inc. -

Perfect Place to Pedal

Perfect place to pedal Unchallenging terrain of Pennsylvania trail offers beautiful views, chance to see animals By Bob Downing, Beacon Journal staff writer Published on Sunday, June 13, 2010 The Allegheny River Trail stretches 34.2 miles north-south next to the Allegheny River in western Pennsylvania. (photo by Bob Downing) BELMAR, Pa.: The Sandy Creek Trail is one of the prettiest rail trails you will ever find. It's also where I ran into an unusual critter: a porcupine. That's not something you will find in Ohio, unless it is in a zoo. The quilled creature was munching on plants along the trail. I pedaled up and got a close look at the scraggly and bedraggled little porcupine as it waddled away. I took its picture without getting stuck with quills, but it was obvious that the porcupine was very glad to see me get back on my bike and pedal off. Welcome to the wild Penn's Woods country along the Sandy Creek Trail in northwestern Pennsylvania. The 12-mile bike-and-hike trail near Franklin features one spectacular trestle, an old tunnel and seven bridges over the splashy and wild East Sandy Creek. The wood-decked trestle over the Allegheny River is 1,385 feet long and about 80 feet above the river. From atop the Belmar Bridge, you can see a long, long way and almost kiss the clouds. A pair of white-headed adult bald eagles flapped overhead in search of dead fish for a meal. The bridge was built in 1907 by local oil man Charles Miller and John D. -

Allegheny River from the Kinzua Dam (Near Warren) to East Brady

;:j?_ Y'f; lfJ2rf Efr- ~8 gf 1 o2 8 ALLEGHENY WILD AND SCENIC RIVER STUDY REPORT AND DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT U. S. Department of Agriculture - Forest Service . ! e Allegheny National F?rest, Warren, PA 16365·' ... ~ Federal Register / Vol. 53, No. 241 / Thursday, December 15, 1988 / Notices 50451 project must submit to the Commission, 385.210, 385.211, 385.214. In determining a. Type of Application: Preliminary on or before the specified comment date the appropriate action to take, the Permit. for the particular application, the Commission will consider all protests or b. Project No.: 10667-000. competing application or a notice of other comments filed, but only those c. Date Filed: September 27, 1988. intent to file such an application (see 18 who file a motion to intervene in d. Applicant: Youghiogheny CFR 4.36 (1985)). Submitting a timely accordance with the Commission's Hydroelectric Authority. notice of intent allows an interested Rules may become a party to the person to file the competing preliminary proceeding. Any comments, protests, or e. Name of Project: Tionesta Dam permit application no later than 30 days motions to intervene must be received Hydro Project. after the specified comment date for the on or before the specified comment date f. Location: On the Tionesta Creek, in particular application. for the particular application. Forest County, Pennsylvania. A competing preliminary permit g. Filed Pursuant to: Federal Power C. Filing and Service of Responsive application must conform with 18 CFR Act 16 U.S.C. 791(a) 825(r). Documents 4.30(b) (1) and (9) and 4.36. -

2) Management Plan Augmentation Technical

Oil Region National Heritage Area Plan Augmentation - 12/18/06 2. Background to the Plan 2.1. Evolution and Scope of the Oil Region Heritage Area The Governor of Pennsylvania designated the Oil Heritage Region as an official Pennsylvania Heritage Park in 1994. The Oil Region is one of several Pennsylvania Heritage Parks that is part of a state-wide program whose purpose is to preserve Pennsylvania’s rich industrial heritage and to use heritage resources as catalysts for community pride and revitalization. 2.1.1. Establishment of the Oil Region National Heritage Area Federal Public Law 108-447 (enacted in December, 2004), Division J, Title VI, 118 Stat. 2809 officially designated Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage Region as a National Heritage Area. The legislation describes the steps necessary to fully activate this new National Heritage Area, including updating its Management Plan, preparing an Environmental Assessment in compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act, and compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act. 2.1.2. Brief Description of the ORNHA, including Boundaries The Oil Heritage Region is one of the most authentic and powerful of the heritage areas in the United States. The form and culture of this region bear the imprint of the oil industry: from the town centers that were developed with oil profits to the oil leases and equipment that dot the landscape and are often plainly visible from the road. The story of oil is interpreted in many venues, ranging from the state-operated Drake Well Museum (including a National Historic Landmark on the site where the initial well was drilled) to small locally managed museums and collections. -

Ohio Archaeologist Volume 28 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 28 NO. 2 SPRING 1978 The Archaeological Society of Ohio Officers—terms expire 1978 Robert Harter, 1961 Buttermilk Hill, Delaware, Ohio President—Jan Sorgenfrei, Jeff Carskadden, 2686 Carol Drive, Zanesville, Ohio 2985 Canterbury Drive, Lima, Ohio 45805 Associate Editor, Martha P. Otto, Vice President—Steve Fuller, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio 4767 Hudson Drive, Stow, Ohio 44224 All articles, reviews and comments on the Ohio Archae Executive Secretary—Dana L. Baker, ologist should be sent to the Editor. Memberships, re West Taylor St., Mt. Victory, Ohio 43340 quests for back issues, changes of address, and other Treasurer—Don Bapst, matter should be sent to the business office. 2446 Chambers Ave., Columbus, Ohio 43223 Recording Secretary—Mike Kish, PLEASE NOTIFY BUSINESS OFFICE IMMEDIATELY 39 Parkview Ave., Westerville, Ohio 43081 OF ADDRESS CHANGES. BY POSTAL REGULATIONS Editor—Robert N. Converse, SOCIETY MAIL CANNOT BE FORWARDED. P.O. Box 61, Plain City, Ohio 43064 Editorial Office Trustees P. O. Box, Plain City, Ohio 43064 Terms expire Ensil Chadwick, 119 Rose Ave., Business Office Mount Vernon, Ohio 1978 Summers Redick, 35 West River Glen Drive, Wayne A. Mortine, Scott Drive, Worthington, Ohio 43085 Oxford Heights, Newcomerstown, Ohio 1978 Charles H. Stout, 91 Redbank Drive, Membership and Dues Fairborn, Ohio 1978 Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are Max Shipley, 705 S. Ogden Ave., payable on the first of January as follows: Regular mem Columbus, Ohio 1978 bership $7.50; H usband and wife (one copy of publication) William C. Haney, 706 Buckhorn St., $8.50; Contributing $25.00. Funds are used for publish Ironton, Ohio 1980 ing the Ohio Archaeologist. -

Trees and Forests of the Allegheny River Islands Wilderness and Nearby Islands: Interim Report Through December 2011

Trees and Forests of the Allegheny River Islands Wilderness and Nearby Islands: Interim Report through December 2011 By Edward Frank, Dale Luthringer, Carl Harting, and Anthony Kelly Native Tree Society Special Publication Series: Report #10 Native Tree Society Special Publication Series: Report #10 http://www.nativetreesociety.org http://www.ents-bbs.org Mission Statement: The Native Tree Society (NTS) is a cyberspace interest groups devoted to the documentation and celebration of trees and forests of the eastern North America and around the world, through art, poetry, music, mythology, science, medicine, wood crafts, and collecting research data for a variety of purposes. Our discussion forum is for people who view trees and forests not just as a crop to be harvested, but also as something of value in their own right. Membership in the Native Tree Society and its regional chapters is free and open to anyone with an interest in trees living anywhere in the world. Current Officers: President—Will Blozan Vice President—Lee Frelich Executive Director—Robert T. Leverett Webmaster—Edward Frank Editorial Board, Native Tree Society Special Publication Series: Edward Frank, Editor-in-Chief Robert T. Leverett, Associate Editor Will Blozan, Associate Editor Don C. Bragg, Associate Editor Membership and Website Submissions: Official membership in the NTS is FREE. Simply sign up for membership in our bulletins board at http://www.ents- bbs.org Submissions to the website or magazine in terms of information, art, etc. should be made directly to Ed Frank at: [email protected] The Special Publication Series of the Native Tree Society is provided as a free download in Adobe© PDF format through the NTS website and the NTS BBS. -

Preservationhappenshere!

#PreservAtionHappensHere! 2018-2023 Pennsylvania’s Statewide Historic Preservation Plan Community Connections: Planning for Preservation in Pennsylvania Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation O ce PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL AND MUSEUM COMMISSION https://phmc.info/PresPlan | a During the public engagement process, the PA SHPO asked Pennsylvanians what the term "historic preservation" means to them. This word cloud reflects their responses, with the largest words representing the ones we heard most often. PENNSYLVANIA’S POSTCARD COLLECTION Many of the illustrations in this document are images from postcards. Postcards were used in the late 19th century and throughout the 20th century for advertising, greetings, and political and patriotic purposes. The images here were drawn from the Postcard Collection (MG-213) of the Pennsylvania State Archives, which includes more than 29,000 images depicting urban and rural scenes; public, commercial, industrial and private buildings; historic sites; churches; bridges and streams; railroads; highways and roads; and more. The wide-ranging collection, currently being digitized by PHMC, provides the perfect backdrop to illustrate Pennsylvania’s diverse historic landscape and its prominence in the tourism industry. In the tradition of many of the postcards in the collection, we would like to say, “Welcome to Pennsylvania!” #PreservAtionHappensHere TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Purpose of This Plan 6 Planning Cycle 7 Vision for Preservation in Pennsylvania 8 The Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation -

National Heritage Area P E N N S Y L V a N I A

NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA P E N N S Y L V A N I A TITUSVILLE OIL CITY CRANBERRY FRANKLIN EMLENTON FOXBURG www.grabtrails.com www.oilregion.org 800.483.6264 CONTENTS Heritage Trails . 3 Titusville . 5 Oil City . 7 Cranberry . 10 Franklin . .11 Emlenton . 15 Foxburg . .16 Welcome! We are delighted to introduce you to the Oil the eastern portion of Crawford County as the Oil Region Region National Heritage Area! You’re invited to visit the National Heritage Area, with the Oil Region Alliance as its Attractions . 17 friendly people and fascinating locations in “The Valley federally designated manager. The same territory has been Recreation/Parks . .18 That Changed The World” situated in rural northwestern an official Pennsylvania Heritage Area since 1994. Pennsylvania. As its name suggests, the Oil Region National Heritage Arts & Culture . 19 The National Park Service defines a National Heritage Area Area’s special legacy is being the birthplace of the modern Culture Trails . 21 as a place designated by Congress where natural, cultural, petroleum industry. From Edwin Drake’s 1859 drilling of and historic resources combine to form a cohesive, the first commercial oil well along Oil Creek near Titusville, Taste Trails. 22 nationally distinctive landscape arising from patterns of through the early oil booms and the more recent natural gas 1 human activity shaped by geography. production booms, into today and beyond, this region’s Detailed City Maps . 23 2 These patterns make National Heritage Areas architecture, economics, festivals, place names, and Oil Region Map . .25 representative of the diverse national experience through tremendous collection of historic items have been shaped the physical features that remain, the traditions that have by this industry and the continuing population shifts along Events/Festivals . -

Trees and Forests of the Allegheny River Islands Wilderness and Nearby Islands: Interim Report Through December 2011

Trees and Forests of the Allegheny River Islands Wilderness and Nearby Islands: Interim Report through December 2011 By Edward Frank, Dale Luthringer, Carl Harting, and Anthony Kelly Native Tree Society Special Publication Series: Report #10 Native Tree Society Special Publication Series: Report #10 http://www.nativetreesociety.org http://www.ents-bbs.org Mission Statement: The Native Tree Society (NTS) is a cyberspace interest groups devoted to the documentation and celebration of trees and forests of the eastern North America and around the world, through art, poetry, music, mythology, science, medicine, wood crafts, and collecting research data for a variety of purposes. Our discussion forum is for people who view trees and forests not just as a crop to be harvested, but also as something of value in their own right. Membership in the Native Tree Society and its regional chapters is free and open to anyone with an interest in trees living anywhere in the world. Current Officers: President—Will Blozan Vice President—Lee Frelich Executive Director—Robert T. Leverett Webmaster—Edward Frank Editorial Board, Native Tree Society Special Publication Series: Edward Frank, Editor-in-Chief Robert T. Leverett, Associate Editor Will Blozan, Associate Editor Don C. Bragg, Associate Editor Membership and Website Submissions: Official membership in the NTS is FREE. Simply sign up for membership in our bulletins board at http://www.ents- bbs.org Submissions to the website or magazine in terms of information, art, etc. should be made directly to Ed Frank at: [email protected] The Special Publication Series of the Native Tree Society is provided as a free download in Adobe© PDF format through the NTS website and the NTS BBS.