Preservationhappenshere!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16 Use 461 Note TITLE I—SOUTHWESTERN PENNSYLVA NIA HERITAGE PRESERVATION COM- MISSION

102 STAT. 4618 PUBLIC LAW 100-698—NOV. 19, 1988 Public Law 100-698 100th Congress An Act Nov. 19, 1988 To establish in the Department of the Interior the Southwestern Pennsylvania [H.R. 3313] Heritage Preservation Commission, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, 16 use 461 note. SECTION 1. FINDINGS AND PURPOSE. (a) FINDINGS.—The Congress finds that— (1) the iron and steelmaking, coal, and transportation indus tries and the labor of their workers contributed significantly to America's movement westward, allowed for the growth of the Nation's cities, and helped fuel and move its industrial growth and development and establish its standing among nations of the world; (2) there are only a few recognized historic sites that are devoted to portraying the development and growth of heavy industry and the industrial labor movement in America; and (3) the 9-county region in southwestern Pennsylvania known as the Allegheny Highlands contain significant examples of iron and steel, coal, and transportation industries, and is a suitable region in which the story of American industrial heritage can be appropriately interpreted to present and future generations. (b) PURPOSE.—In furtherance of the findings set forth in subsec tion (a) of this section, it is the purpose of this Act to establish, through a commission representing all concerned levels of govern ment, the means by which the cultural heritage of the 9-county region in southwestern Pennsylvania associated with the three basic industries of iron and steel, coal, and transportation may be recog nized, preserved, promoted, interpreted, and made available for the benefit of the public. -

CHARTER DAY 2014 Sunday, March 9 Celebrate Pennsylvania’S 333Rd Birthday!

PENNSYLVANIA QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER HERITAGE WINTER 2014 TM® FOUNDATION CHARTER DAY 2014 Sunday, March 9 Celebrate Pennsylvania’s 333rd birthday! The following sites expect to be open, but please confirm when planning your visit: Anthracite Heritage Museum Brandywine Battlefield Conrad Weiser Homestead Cornwall Iron Furnace Young visitors enjoy a Charter Daniel Boone Homestead Chat with archivist Drake Well Museum and Park Joshua Stahlman. Eckley Miners’ Village Ephrata Cloister Erie Maritime Museum Fort Pitt Museum Graeme Park PHMC/PHOTO BY DON GILES Joseph Priestley House Landis Valley Village and Farm Museum Old Economy Village Pennsbury Manor Pennsylvania Military Museum Railroad Museum of PHMC/EPHRATA CLOISTER Pennsylvania Student Historians at Ephrata Cloister, The State Museum of Pennsylvania Charter Day 2013. Washington Crossing Historic Park Pennsylvania’s original Charter will be on exhibit at Pennsbury Manor for Charter Day 2014, celebrated by PHMC on Sunday, March 9! The 1681 document, granting Pennsylvania to William Penn, is exhibited only once a year at The State Museum by the Pennsylvania State Archives. Located in Morrisville, Bucks County, Pennsbury Manor is the re-created private country estate of William Penn which opened to the PHMC/PHOTO BY BETH A. HAGER public as a historic site in 1939. Charter Day will kick off Pennsbury’s 75th A Harrisburg SciTech High docent on anniversary celebration. Charter Day at The State Museum. www.phmc.state.pa.usJoin or renew at www.paheritage.org PENNSYLVANIA HERITAGEPHF NEWSLETTER Winter 2014 39 39 HIGHLIGHTS FOR JANUARY–MARch 2013 C (We’re changing our calendar! We will no longer list the full ERIE MARITIME MUSEUM AND event calendar in our quarterly newsletter but will highlight exhibits and FLAGSHIP NIAGARA selected events. -

414 Act 1988-72 LAWS of PENNSYLVANIA No. 1988-72 an ACT HB 1731 Amending Title 37

414 Act 1988-72 LAWS OF PENNSYLVANIA No. 1988-72 AN ACT HB 1731 Amending Title 37 (Historical and Museums) of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes, adding provisions relating to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, publications and historical societies; reestablishing the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; further providing for the powers andduties of the commission; providing forthe Brandywine Battlefield Park Commission and the Washington Crossing Park Commission; establish- ing an official flagship of Pennsylvania; abolishing certain advisory boards; adding provisionsrelating to concurrent jurisdiction; andmaking repeals. TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE 37 HISTORICAL AND MUSEUMS Chapter 1. General Provisions § 101. Short title of title. § 102. Declaration of policy. § 103. Definitions. § 104. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Chapter 3. Powers and Duties of Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission § 301. General powers and duties. § 302. Specific powers and duties. § 303. Sites. § 304. Personal property. § 305. Documents. § 306. Publications and reproductions. § 307. Qualified historical and archaeological societies~ Chapter 5. Historic Preservation § 501. Short title of chapter. § 502. Powers and duties of commission. § 503. Inclusion of property on register. § 504. Historic Preservation Board. § 505. Powers and duties of board. § 506. Archaeological field investigations on Commonwealth land. § 507. Cooperation by public officials with the commission. § 508. Interagency cooperation. § 509. Transfer of Commonwealth land involving historic resources. § 510. Approval of construction affecting historic resources. § 511. Criminal penalties. SESSION OF 1988 Act 1988-72 415 § 512. Enforcement of historic preservation laws and policies. Chapter 7. Historic Properties § 701. Title to historic property. § 702. Powers over certain historic property. § 703. Brandywine Battlefield. § 704. Washington Crossing. § 705. United States Brig Niagara. -

Petroglyphs of Pennsylvania Pennsylvania of Petroglyphs

12/07 by Larry A. Smail. A. Larry by Petroglyphs Landing Parker’s is painting cover The www.phmc.state.pa.us/bhp/ • Washington, D.C. 20240 D.C. Washington, www.PaArchaeology.state.pa.us • 1849 C Street, N.W. Street, C 1849 www.pennsylvaniaarchaeology.com • National Park Service Park National Office of Equal Opportunity Equal of Office obtained at: obtained desire further information, please write to: write please information, further desire recording forms, and instructions can be be can instructions and forms, recording discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you you if or above, described as facility or activity, program, any in against discriminated origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been been have you believe you If programs. assisted federally its in age or disability, origin, Archaeological Site Survey (PASS). Information, Information, (PASS). Survey Site Archaeological Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national national color, race, of basis the on discrimination prohibits Interior the of Department record these locations with the Pennsylvania Pennsylvania the with locations these record Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. U.S. the amended, as 1975, of Act Discrimination Age the and 1973, of Act Rehabilitation of archaeological sites, we encourage you to to you encourage we sites, archaeological of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the the of 504 Section 1964, of Act Rights Civil the of VI Title Under properties. -

Project Archaeology: Pennsylvania

PROJECT ARCHAEOLOGY: PENNSYLVANIA AN EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS BASED CURRICULUM FOR GRADES FOUR THROUGH EIGHT STUDENT TEXT (FOR USE WITH LESSON PLAN BOOK) AN EDUCATIONAL INITIATIVE OF THE PENNSYLVANIA ARCHAEOLOGICAL COUNCIL EDUCATION COMMITTEE THIS PROJECT IS SUPPORTED BY A GRANT FROM THE PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL AND MUSEUM COMMISSION PROJECT ARCHAEOLOGY: PENNSYLVANIA AN EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS BASED CURRICULUM FOR GRADES FOUR THROUGH EIGHT STUDENT TEXT (FOR USE WITH LESSON PLAN BOOK) Project Directed and Edited by Renata B. Wolynec, Ph. D. Contributing Authors: Renata B. Wolynec, Ph. D. Ellen Dailey Bedell, Ph. D. Edinboro University of PA Ellis School, Pittsburgh Sarah Ward Neusius, Ph. D. Beverly Mitchum Chiarulli, Ph. D. Indiana University of PA Indiana University of PA Joseph Baker PA Department of Transportation, Harrisburg SECTION ONE – BASIC CONCEPTS Chapter 1 -- What Is Anthropology? (Wolynec) Chapter 2 -- What Is Archaeology? (Wolynec) Chapter 3 -- Meet an Archaeologist (Wolynec, Bedell, Neusius, Baker, and Chiarulli) Chapter 4 -- How Do Archaeologists Do Their Work? (Wolynec) Chapter 5 -- How Old Is It? (Wolynec) SECTION TWO – PENNSYLVANIA BEFORE THE EUROPEANS Chapter 6 -- History and Culture in Pennsylvania Place Names (Wolynec) Chapter 7 -- What Was Pennsylvania Like Before European Contact? (Neusius) Chapter 8 -- Where Did the Ancestors of Native Americans Come From? (Wolynec) Chapter 9 -- Native American History in Pennsylvania Before the Europeans (Wolynec) SECTION THREE - COMPARING CULTURES Chapter 10 -- What Basic Needs Do -

PHMC-Commission-Meeting-Minutes

PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL AND MUSEUM COMMISSION MARCH 4, 2020 MINUTES The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission met on March 4, 2020 in the 5th Floor Board Room of the State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The following Commissioners were present: Nancy Moses – Chair, Ophelia Chambliss, Andrew Masich, Philip Zimmerman, William Lewis, Robert Savakinus, David Schuyler, Glenn Miller (Department of Education) and Representative Robert Matzie. Fred Powell, Kate Flessner for Senator Joseph Scarnati, Senator Andrew Dinniman and Representative Parke Wentling participated via conference call. The following staff were present: Andrea Lowery, Howard Pollman, David Bohanick, David Carmicheal, Andrea MacDonald, Brenda Reigle, Beth Hager and Karen Galle. Rodney Akers and Gerard Leone served as legal counsel. Glenn Holliman represented the Pennsylvania Heritage Foundation. Tony Smith, Hugh Moulton, Suzanne Bush and Former State Representative Kate Harper represented The Highlands Historical Society. Charlene Bashore, Esq., Republican Legal Staff. Liz Weber, consultant for PHMC Strategic Planning. I. CALL TO ORDER PHMC Chairwoman, Nancy Moses called the meeting to order at 10am. At this time, she asked everyone in the room and on the phone to introduce themselves. Chairwoman Nancy Moses announced that Cassandra Coleman, Executive Director of America250PA will report on her project – Semiquincentennial for the 250th Anniversary of the founding of the United States. 1 II. APPROVAL OF DECEMBER 4, 2019 MINUTES Chairwoman Nancy Moses called for a motion to approve the minutes from the December 4, 2019 meeting. MOTION: (Zimmerman/Turner) Motion to accept the minutes as presented from December 4, 2019 meeting was approved. 13 in favor/0 opposed/0 abstention. III. CHAIRWOMAN’S REMARKS Chairwoman Nancy Moses thanked commissioners and staff who work together on different issues the commission confronts. -

French & Indian War Bibliography 3.31.2017

BRITISH, FRENCH, AND INDIAN WAR BIBLIOGRAPHY Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center 1. ALL MATERIALS RELATED TO THE BRITISH, FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR (APPENDIX A not included) 2. FORTS/FORTIFICATIONS 3. BIOGRAPHY/AUTOBIOGRAPHY 4. DIARIES/PERSONAL NARRATIVES/LETTERS 5. SOLDIERS/ARMS/ARMAMENTS/UNIFORMS 6. INDIAN CAPTIVITIES 7. INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE 8. FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR HISTORIES 9. PONTIAC’S CONSPIRACY/LORD DUNMORE’S WAR 10. FICTION 11. ARCHIVAL APPENDIX A (Articles from the Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine and Pittsburgh History) 1. ALL MATERIALS RELATED TO THE BRITISH, FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR A Brief History of Bedford Village; Bedford, Pa.; and Old Fort Bedford. • Bedford, Pa.: H. K. and E. K. Frear, 1961. • qF157 B25 B853 1961 A Brief History of the Colonial Wars in America from 1607 to 1775. • By Herbert T. Wade. New York: Society of Colonial Wars in the State of New York, 1948. • E186.3 N532 No. 51 A Brief History of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. • Edited by Sir Edward T. H. Hutton. Winchester: Printed by Warren and Son, Ltd., 1912. • UA652 K5 H9 A Charming Field For An Encounter: The Story of George Washington’s Fort Necessity. • By Robert C. Alberts. National Park Service, 1975. • E199 A33 A Compleat History of the Late War: Or Annual Register of Its Rise, Progress, and Events in Europe, Asia, Africa and America. • Includes a narrative of the French and Indian War in America. Dublin: Printed by John Exshaw, M.DCC.LXIII. • Case dD297 C736 A Country Between: The Upper Ohio Valley and Its Peoples 1724-1774. -

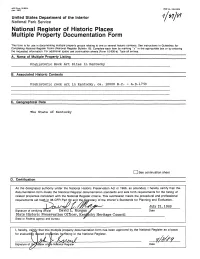

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

(Jan.,N,PS ^V°-900-bI9o7) ' .-. 0MB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing _______Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in Kentucky________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ ___ Prehistoric rock art in Kentucky, ca. 10000 B.C. - A.D.17 50 C. Geographical Data I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set foittnn 36 CFR Part 60 and the^ejjretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. July 21, 1989 Signature of certifying official David L. Morgan ^^ Date State Historic Preservation Officer, Kerdrocky Heritage Council___________ State or Federal agency and bureau ' I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluatirjfg related proj$)erties fcyfisting in the National Register. ^S*£* fj' /] / v^^r" 7 V l^W" - " ~ ' Signature of tb^Keeper of/Me National Register Date E. -

Pennsylvania Title 37- the Pennsylvania History Code

TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE 37 HISTORICAL AND MUSEUMS Chapter 1. General Provisions § 101. Short title of title. § 102. Declaration of policy. § 103. Definitions. § 104. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Chapter 3. Powers and Duties of Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission § 301. General powers and duties. § 302. Specific powers and duties. § 303. Sites. § 304. Personal property. § 305. Documents. § 306. Publications and reproductions. § 307. Qualified historical and archaeological societies. Chapter 5. Historic Preservation § 501. Short title of chapter. § 502. Powers and duties of commission. § 503. Inclusion of property on register. § 504. Historic Preservation Board. § 505. Powers and duties of board. § 506. Archaeological field investigations on Commonwealth land. § 507. Cooperation by public officials with the commission. § 508. Interagency cooperation. § 509. Transfer of Commonwealth land involving historic resources. § 510. Approval of construction affecting historic resources. § 511. Criminal penalties. § 512. Enforcement of historic preservation laws and policies. Chapter 7. Historic Properties § 701. Title to historic property. § 702. Powers over certain historic property. § 703. Brandywine Battlefield (Repealed). § 704. Washington Crossing (Repealed). § 705. United States Brig Niagara. Chapter 9. Concurrent Jurisdiction § 901. Cession of concurrent jurisdiction. § 902. Sites affected. § 903. Transfer of personal property. § 904. Acceptance by United States. § 905. Acceptance by Governor. § 906. Police service agreements. TITLE 37 HISTORICAL AND MUSEUMS Chapter 1. General Provisions 3. Powers and Duties of Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission 5. Historic Preservation 7. Historic Properties 9. Concurrent Jurisdiction Enactment. Unless otherwise noted, the provisions of Title 37 were added May 26, 1988, P.L.414, No.72, effective immediately. CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS Sec. 101. Short title of title. 102. -

Pennsylvania: a Holy Experiment

January - March 2020 Pennsylvania: A Holy Experiment William Penn, a Quaker, was looking for a haven in the New World where he and other Quakers could practice their religion freely and without per- secution. He asked King Charles II to grant him land in the territory be- tween Lord Baltimore’s province of Maryland and the Duke of York’s province of New York in order to sat- isfy a debt owed to his father’s estate. With the Duke’s support, Penn’s peti- tion was granted. Charles signed the Charter of Pennsylvania on March 4, 1681, and it was officially proclaimed INSIDE THIS ISSUE: on April 2. With this act, the King not FROM THE PRESIDENT 2 only paid his debt to the Penn family, A NEW BOOK ABOUT 3 but rid England of troublesome ELIZABETH GRAEME Quakers who often challenged the NEWSBRIEFS 3 policies of the Anglican church. LUNCH & LEARN: WOMEN & THE 4 Penn was granted 45,000 acres and, at FIGHT FOR THE RIGHT TO VOTE Charter Day Open Charles’ insistence, named the new SEASONAL PLANTERS 5 House—Free Tours colony Pennsylvania (meaning TEA WITH LOUISA MAY ALCOTT 5 Penn’s Woods) in honor of his father, 2020 CALENDAR 6 March 8—12 noon - 4:00 p.m. Admiral William Penn. Penn intend- ed to establish Pennsylvania as a Ho- CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR 6 2019 WEDDING COUPLES Join Graeme Park on Sunday, ly Experiment built on the Quaker March 8 from 12 to 4 (last admis- 2019 LIVING HISTORY 7 ideals of religious tolerance, belief in ROUND-UP sion to house at 3:15) in celebrat- the goodness of human nature, par- ing the 339th anniversary of the ticipatory government, and brotherly UPCOMING founding of Pennsylvania. -

PHMC-Commission-Meeting-Minutes

PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL AND MUSEUM COMMISSION MARCH 19, 2008 MINUTES A meeting of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission was held on March 19, 2008, in the 5th Floor Board Room of the State Museum, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The following Commissioners were present: Rhonda Cohen, Senator Jim Ferlo, Laura Fisher, Janet Klein, Kathleen Pavelko, Ann Marie Segilia for Representative Scott Petri, Casey Long for Senator Joseph Scarnati, Representative Rick Taylor and Clare Zales. The following staff were present: Barbara Franco, Jean Cutler, Jason Gerard, Beth Hager, Jack Leighow, Rhonda Newton, David Haury, Howard Pollman, Wasyl Polischuk, Brenda Reigle, Ted Walke and Kirk Wilson. Andrea Bowman, from the Office of General Counsel, was present as PHMC Counsel. Jim Pickman, Civil War Consultant for PA Heritage Society was present. I. CALL TO ORDER Ms. Cohen called the meeting to order at 9:30 a.m. II. APPROVAL OF MINUTES FROM NOVEMBER 28, 2007 Ms. Cohen called for a motion to approve the minutes from November 28, 2007. On motion by Ms. Klein, seconded by Senator Ferlo, the minutes were approved. III. CHAIRMAN’S REPORT Ms. Cohen read a report from Chairman Spilove: • On December 5, 2007, Chairman Spilove attended a marker dedication for the Masonic Temple. • December 12, 2007, Chairman Spilove attended a budget meeting with Barbara Franco, Wasyl Polischuk and Melody Henry. The group met with Secretary Masch, Steve Kniley to review the Governor’s fiscal recommendations for the upcoming year in Harrisburg, PA. • December 12, 2007, Chairman Spilove attended the PA Council on the Arts Joint Commission Meeting at the Red Door in Harrisburg, PA. -

Newsletter Summer 2021 Paheritage.Org

PA-SHARE Strengthens Preservation PENNSYLVANIA HERITAGE FOUNDATION NEWSLETTER SUMMER 2021 PAHERITAGE.ORG PHF Provides Access to Trails of History Programs with Its Enhanced Website Creativity is often a result of adver- sity. During this past year, the Penn- sylvania Heritage Foundation has utilized the technology of our age. PHF’s website has been enhanced with numerous new features and a plethora of opportunities to enrich one’s knowledge of our heritage. It has opened the door to visually expe- rience the amazing offerings of the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission from the comfort of your home. Among our increased member- ship benefits is our new twice-a- month e-digest highlighting the commonwealth’s points of interest, historic sites, and the fascinating people who have shaped the culture of present-day Pennsylvania. This PHF provides easy access through its website to the virtual programs of Trails of History sites such as feature is not to be missed. the Pennsylvania Lumber Museum, which offers a virtual tour, photography exhibits and special events. Photo, Pennsylvania Lumber Museum, PHMC As we continue the story, let us take encouragement by realizing the citizens of Pennsylvania have stood together through innumerable Thank you for supporting and being a member of the Pennsylva- challenges in our 340 years as a commonwealth. Our history is nia Heritage Foundation. Please continue to join us as we explore brimming with stories of how we as a people have overcome trials our past and increase our understanding of the present. and tribulations. Now, a new chapter in the Pennsylvania story is being written.