Examining Professional Golf Organisations' Online Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCOREBOARD Sports on TV A.M., ESPN2 Trenton Thompson

TimesDaily |Friday, June 7, 2019 D3 SPORTS ON TV/RADIO Today Super Regional, Game 1, 11 SCOREBOARD Sports on TV a.m., ESPN2 Trenton Thompson. Harold Varner III 33-35—68 AUTO RACING •NCAATournament: Florida PRO BASEBALL HORSE RACING Ryan Palmer 36-32—68 •FormulaThree: WSeries, State vs.LSU,Baton Rouge HOCKEY Kelly Kraft 35-33—68 MLB BELMONT ODDS National Hockey League Scott Stallings 34-34—68 Belgium (taped), 3p.m., NBCSN Super Regional,Game 1, 2p.m., All times Central The field for Saturday’s 151st Belmont Stakes, DALLAS STARS —Signed DRoman Polak Sepp Straka35-33—68 •ARCASeries: The Michigan ESPN AMERICAN LEAGUE with post position, horse, jockey and odds: and FMattais Janmark to one-year contract Kyle Jones 33-35—68 EAST DIVISION WLPCT.GB PP,HORSE JOCKEY ODDS extensions. Jim Knous 35-33—68 200, 5p.m., FS1 •NCAATournament: Stanford New York 39 22 .639 — 1. Joevia Jose Lezcano 30-1 Joey Garber 32-36—68 •NASCAR GanderOutdoors vs.Mississippi State, Starkville TampaBay 37 23 .617 1½ 2. Everfast Luis Saez 12-1 SOCCER Ryan Yip 35-33—68 Boston 33 29 .532 6½ 3. Master Fencer Julien Leparoux 8-1 Major League Soccer Ben Crane 35-34—69 Truck Series: The Rattlesnake Super Regional, Game 1, 2p.m., Toronto 23 39 .371 16½ 4. TaxIradOrtiz Jr. 15-1 MLS —Fined Portland Timbers MSebastian Trey Mullinax 35-34—69 George McNeill 37-32—69 400, 8p.m., FS1 ESPN2 Baltimore1943.306 20½ 5. Bourbon WarMikeSmith 12-1 Blanco and DLarrysMabiala for violating heads CENTRAL DIVISION WLPCT.GB 6. -

*Schedule As of January 14, 2019 and Subject to Change Denotes Major Championship

*Schedule as of January 14, 2019 and subject to change denotes Major Championship 2019 Champion Date Tournament/Contact Host Club Purse (Defending Champion) Jan. 14-20 Diamond Resorts Tournament of Champions Four Season Golf & Sports Club Orlando $1,200,000 (Inaugural Year) Presented by Insurance Office of America 3451 Golf View Drive Lake Buena Vista, Florida 32830 Feb. 4-10 Vic Open 13th Beach Golf Links $1,100,000 (Minjee Lee) 1732 Barwon Heads Road, Barwon Heads Vitctoria, Australia 3227 Feb. 11-17 ISPS Handa Women’s Australian Open The Grange Golf Club $1,300,000 (Jin Young Ko) White Sands Drive Grange, South Australia Feb. 18-24 Honda LPGA Thailand Siam Country Club, Old Course $1,600,000 (Jessica Korda) 50 M.9, T, Pong, Banglamung Chonburi, Thailand 20150 Feb. 25- Mar. 3 HSBC Women’s World Championship Sentosa Golf Club, New Tanjong Course $1,500,000 (Michelle Wie) 27 Bukit Manis Road Singapore 099892 Mar. 18-24 Bank of Hope Founders Cup JW Marriott Desert Ridge, Wildfire Golf Club $1,500,000 (Inbee Park) 5350 East Marriott Drive Phoenix, Arizona 85054 Mar. 25-31 Kia Classic Park Hyatt Aviara Resort, Aviara Golf Club $1,800,000 (Eun-Hee Ji) 7447 Batiquitos Drive Carlsbad, California 92009 Apr. 1-7 ANA Inspiration Mission Hills Country Club $3,000,000 (Pernilla Lindberg) 34600 Mission Hills Drive Rancho Mirage, California 92270 Apr. 15-20 (Sat. finish) LOTTE Championship Ko Olina Golf Club $2,000,000 (Brooke Henderson) 92-1220 Aliinui Drive, Kapolei Oahu, Hawaii 96707 Apr. 22-28 Hugel-Air Premia LA Open Wilshire Country Club $1,500,000 (Moriya Jutanugarn) 301 N Rossmore Ave Los Angeles, California 90004 Apr. -

Wentworth Names Georgia Hall As Ambassador

WENTWORTH NAMES GEORGIA HALL AS AMBASSADOR London, May 2019: Wentworth Club, the world-famous Golf and Country Club, has announced current Women’s British Open title holder Georgia Hall as Ambassador. The 23-year-old English professional golfer will utilise Wentworth’s 3 Geo-accredited Championship 18-hole courses as her home training base over the next three years. The former British number one will take full advantage of the vast state-of-the-art facilities the Club and course offers, including SubAir Sport Systems across all 18 holes of the West course, the UK’s only TaylorMade performance lab, VR Golf simulation technology, TopTracer driving range, innovative eGym, and a wellness centre catered for by recognised nutritionists. "I was delighted to be invited to be Ambassador at Wentworth, as I’ve always aspired to have access to leading practice facilities such as theirs. Practice has never been this fun. I’m spoiled by the technology available to support in advancing my personal game, not to mention the beautiful gym and spa spaces. The members and all staff at the club have made me feel extremely welcome and I look forward to strengthening my relationship with all.” Georgia Hall “We are delighted to announce that Georgia Hall has joined Wentworth Club as our new golf ambassador. Bringing youth, skill and passion to Wentworth, we are excited by this new relationship and the opportunities it will provide to our Members.” Ms Please, Woraphanit Ruayrungruang (Wentworth Director) www.wentworthclub.com For press enquiries please contact: Kelly Hogarth [email protected] NOTES TO EDITORS About Wentworth Club For more than nine decades Wentworth Club has been regarded as one of the world’s finest and most prestigious golf and country clubs, famous as the home of the BMW PGA Championship since 1984, host venue to the World Match Play for 43 years and the birthplace of the Ryder Cup. -

PRESS RELEASE LACOSTE SIGNS AMERICAN PROFESSIONAL GOLFER DANIEL BERGER Paris, January, 5Th, 2017 LACOSTE Is Pleased to Announ

PRESS RELEASE LACOSTE SIGNS AMERICAN PROFESSIONAL GOLFER DANIEL BERGER Paris, January, 5th, 2017 LACOSTE is pleased to announce that the brand has entered into a partnership with American professional golfer Daniel Berger. Beginning January 2017, Daniel Berger, 23 years old, will become one of the LACOSTE Ambassadors both on and off the golf course. Daniel Berger turned professional in 2013 and is one of the PGA TOUR’s most exciting talents. After being named the 2014-2015 PGA TOUR Rookie of the Year, he has since further solidified his status as a rising star by joining the elite list of players to have won on TOUR. Berger’s rookie success carried into the 2015-16 PGA TOUR season, claiming his first title at the 2016 FedEx St. Jude Classic. Along with his victory in Memphis, Berger recorded five additional Top-10 finishes and qualified for his second consecutive TOUR Championship. “I am honoured to represent LACOSTE and be part of a truly iconic brand within sport,” said Berger. “LACOSTE’s golf product line combines a classic style with superior performance and is the perfect fit for what I am looking for in an apparel partner. The Company has such a strong heritage in golf, and its commitment to growth, as demonstrated by its partnership with the Presidents Cup, makes this an exciting time to join the LACOSTE team and wear the Crocodile.” “We are proud to welcome Daniel Berger to the LACOSTE team. He embodies perfectly the Crocodile brand’s values of relaxed elegance and joie de vivre.” said Thierry Guibert, LACOSTE Group CEO. -

Vagliano Trophy Royal Porthcawl, Wales 24-25 June 2011

Vagliano Trophy Royal Porthcawl, Wales 24-25 June 2011 Results Day 1 - Friday, 24 June 2011 Foursomes GB&I Score EUROPE Kelly Tidy Sophia Popov 1 2/1 Amy Boulden Lara Katzy Holly Clyburn Alexandra Bonetti 4/3 1 Danielle McVeigh Manon Gidali Kelsey Macdonald Marta Silva 1 1 UP Louise Kenney Camilla Hedberg Pamela Pretswell Therese Kolbaek 1 UP 1 Stephanie Meadow Madelene Sagstrom Total Foursomes 2 2 Singles GB&I Score EUROPE Kelly Tidy 0 1 UP 1 Alexandra Bonetti Amy Boulden 0 4/2 1 Marta Silva Kelsey Macdonald 1 1 UP 0 Celine Boutier Holly Clyburn 0 3/2 1 Therese Kolbaek Leona Maguire 1 3/2 0 Manon Gidali Stephanie Meadow 0 1 UP 1 Madelene Sagstrom Danielle McVeigh 0.5 A/S 0.5 Camilla Hedberg Louise Kenney 0 1 UP 1 Sophia Popov Total Singles 2.5 5.5 Total Day 1 4.5 7.5 Vagliano Trophy Royal Porthcawl, Wales 24-25 June 2011 Results Day 2 - Saturday, 25 June 2011 Foursomes GB&I Score EUROPE Kelly Tidy Alexandra Bonetti 1 3/1 0 Amy Boulden Manon Gidali Kelsey Macdonald Marta Silva 0 2/1 1 Louise Kenney Camilla Hedberg Pamela Pretswell Sophia Popov 0 1UP 1 Stephanie Meadow Lara Katzy Leona Maguire Madelene Sagstrom 1 6/4 0 Danielle McVeigh Therese Kolbaek Total Foursomes 2 2 Singles GB&I Score EUROPE Holly Clyburn 0 1 UP 1 Marta Silva Leona Maguire 1 3/1 0 Celine Boutier Kelsey Macdonald 0 3/2 1 Alexandra Bonetti Stephanie Meadow 0 1 UP 1 Therese Kolbaek Kelly Tidy 0 5/4 1 Lara Katzy Amy Boulden 0 2/1 1 Camilla Hedberg Pamela Pretswell 1 2 UP Madelene Sagstrom Danielle McVeigh 0 3/1 1 Sophia Popov Total Singles 2 6 Total Day 2 4 8 Total Day -

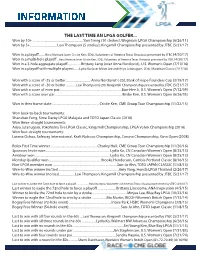

THE LAST TIME an LPGA GOLFER... Won by 10+

THE LAST TIME AN LPGA GOLFER... Won by 10+ ..............................................................Yani Tseng (10 strokes), Wegmans LPGA Championship (6/26/11) Won by 5+ .................................Lexi Thompson (5 strokes), Kingsmill Championship presented by JTBC (5/21/17) Won in a playoff........Haru Nomura (over Cristie Kerr, SD6), Volunteers of America Texas Shootout presented by JTBC (4/30/17) Won in a multi-hole playoff....Haru Nomura (over Cristie Kerr, SD6), Volunteers of America Texas Shootout presented by JTBC (4/30/17) Won in a 3-hole aggregate playoff.................Brittany Lang (over Anna Nordqvist), U.S. Women’s Open (7/10/16) Won in a playoff with multiple players.......Lydia Ko (over Mirim Lee and Ariya Jutanugarn, SD4), Marathon Classic (7/17/16) Won with a score of -25 or better ...............................Anna Nordqvist (-25), Bank of Hope Founders Cup (3/19/17) Won with a score of -20 or better ............Lexi Thompson(-20), Kingsmill Championship presented by JTBC (5/21/17) Won with a score of even par .............................................................................Eun-Hee Ji, U.S. Women’s Open (7/12/09) Won with a score over par ................................................................................... Birdie Kim, U.S. Women’s Open (6/26/05) Won in their home state ..........................................................Cristie Kerr, CME Group Tour Championship (11/22/15) Won back-to-back tournaments: Shanshan Feng, Sime Darby LPGA Malaysia and TOTO Japan Classic (2016) Won three-straight tournaments: Ariya Jutanugarn, Yokohama Tire LPGA Classic, Kingsmill Championship, LPGA Volvik Championship (2016) Won four-straight tournaments: Lorena Ochoa, Safeway International, Kraft Nabisco Championship, Corona Championship, Ginn Open (2008) Rolex First Time winner ......................................................... Charley Hull, CME Group Tour Championship (11/20/16) Sponsors Invite won .............................................................................. -

The Major Date for the Elite in Women's World Golf

PRESS KIT APRIL 2019 01.SPORT THE MAJOR DATE FOR THE ELITE IN WOMEN’S WORLD GOLF As its turns 25, The Evian Championship makes its big midsummer comeback. From 25 to 28 July 2019, the only Grand Slam stage in Continental Europe welcomes the leading 120 women golfers in the world, who are selected according to very tough eligibility criteria. This birthday edition of the Major is of course one of sporting excellence thanks to the quality of the field and its course, with its overall prize purse now $4,100,000. In terms of the course, the Evian Resort Golf Club is even more spectacular with hole 13 young players to bring the talents of tomorrow to the fore, visible when awarding wildcards or shortened to a par 4 and hole 18 reshaped into a par 5, offering a venue to match the event’s at dedicated events (Evian Championship Juniors Cup, Haribo Kids Cup, Evian Junior Event…). status, surrounded by nature in its summer splendour. In addition to the competition itself, the 25th birthday is a big celebration of golf for all of the The 25th anniversary is also the opportunity to highlight The Evian Championship’s societal spectators, from discerning fans to tourists, curious to take part in a global sporting event while role and its steadfast involvement in creating exposure for women’s world golf, working closing on holiday. New packages including the Family Pass or Group Pass will enable everyone to with the athletes, the way it has always been since the tournament was created by Antoine experience the tournament, the sidelines and exclusive events in the best possible conditions. -

Parra Sets the Pace

PARRA SETS THE PACE Spain’s Maria Parra has claimed an early lead in the race to earn a place in the European team at this year’s PING Junior Solheim Cup at GC St. Leon-Rot, Germany. The 17 year-old from Sotogrande tops the European Ranking after claiming 30 points while competing in the Spanish International Ladies’ Amateur Championship at Real Club Pineda de Sevilla. Parra reached the semi-final of the first counting event for this year’s European Ranking before losing 3 & 1 to the eventual winner Olivia Cowan from Germany. The Spaniard heads into the second counting event at the French International Lady Juniors Championship with a 20 point advantage over England’s Alice Hewson, Switzerland’s Albane Valenzuela and compatriot Maria Herraez Galves who collected 10 points in Sevilla. Belgium’s Diane Baillieux (5 points) and Sweden’s Julia Engström (1 point) were the other two eligible players to collect ranking points in Spain. The Spanish International Ladies’ Amateur Championship was the first of eight counting events on this year’s PING Junior Solheim Cup European Ranking with the first six players on the Ranking at the end of the qualification process all earning an automatic place on the European team for the match at GC St. Leon-Rot on September 14- 15. The team will be completed with six Captain’s picks. The second counting event at the French International Lady Juniors Championship at GC St. Cloud, France (April 2-6) will be followed by the German Girls’ Open at GC St. Leon-Rot, Germany (June 5-7), the Ladies’ British Open Amateur Championship at Portstewart GC, Northern Ireland (June 9-13), the European Girls’ Team Championship at Golf Resort Kaskada Brno, Czech Republic (July 7-11), the European Ladies’ Team Championship at Helsingør GC, Denmark (July 7-11) and the ANNIKA Invitational Europe at Bro-Bålsta GK, Sweden (August 4-6) before the qualification process is completed at the Girls’ British Open Championship at West Kilbride GC, Scotland, on August 10-14, 2015. -

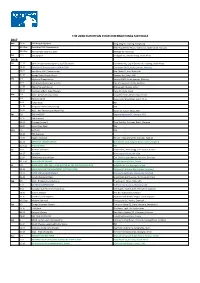

2017 2018 the 2018 European Tour International Schedule

THE 2018 EUROPEAN TOUR INTERNATIONAL SCHEDULE 2017 Nov 23-26 UBS Hong Kong Open Hong Kong GC, Fanling, Hong Kong 30-3 Dec Australian PGA Championship RACV Royal Pines Resort, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia 30-3 Dec AfrAsia Bank Mauritius Open Heritage GC, Mauritius Dec 7-10 Joburg Open Randpark GC, Johannesburg, South Africa 2018 Jan 11-14 BMW SA Open hosted by the City of Ekurhuleni Glendower GC, City of Ekurhuleni, Gauteng, South Africa 12-14 EURASIA CUP presented by DRB-HICOM Glenmarie G&CC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 18-21 Abu Dhabi HSBC Championship Abu Dhabi GC, Abu Dhabi, UAE 25-28 Omega Dubai Desert Classic Emirates GC, Dubai, UAE Feb 1-4 Maybank Championship Saujana G&CC, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 8-11 ISPS Handa World Super 6 Perth Lake Karrinyup CC, Perth, Australia 15-18 NBO Oman Golf Classic Almouj Golf, Muscat, Oman 22-25 Commercial Bank Qatar Masters Doha GC, Doha, Qatar Mar 1-4 WGC - Mexico Championship Chapultepec GC, Mexico City, Mexico 1-4 Tshwane Open Pretoria CC, Waterkloof, South Africa 8-11 Indian Open TBA 15-18 Philippines Golf Championship TBA 21-25 WGC - Dell Technologies Match Play Austin CC, Austin, Texas, USA Apr 5-8 THE MASTERS Augusta National GC, Georgia, USA 12-15 TBA (Europe) 19-22 Trophee Hassan II Royal Golf Dar Es Salam, Rabat, Morocco 26-29 Volvo China Open TBA May 5-6 GolfSixes TBA 10-13 TBA (Europe) 17-20 Belgian Knockout Rinkven International GC, Antwerp, Belgium 24-27 BMW PGA CHAMPIONSHIP Wentworth Club, Virginia Water, Surrey, England 31-3 Jun ITALIAN OPEN TBA Jun 7-10 Austrian Golf Open Diamond CC, Atzenbrugg, near Vienna, Austria 14-17 US OPEN Shinnecock Hills GC, NY, USA 21-24 BMW International Open Golf Club Gut Laerchenhof, Pulheim, Germany 28-1 Jul HNA OPEN DE FRANCE Le Golf National, Paris, France Jul 5-8 DUBAI DUTY FREE IRISH OPEN HOSTED BY THE RORY FOUNDATION Ballyliffin GC, Co. -

PLAYERS GUIDE — Pine Needles Lodge & Golf Club | Southern Pines, N.C

2ND U.S. SENIOR WOMEN’S OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP PLAYERS GUIDE — Pine Needles Lodge & Golf Club | Southern Pines, N.C. — May 16-19, 2019 conducted by the 2019 U.S. SENIOR WOMEN'S OPEN PLAYERS' GUIDE — 1 Exemption List Here are the golfers who are currently exempt from qualifying AMY ALCOTT for the 2019 U.S. Senior Women’s Open Championship, Birth Date: February 22, 1956 with their exemption categories listed. Player Exemption Category Player Exemption Category Birthplace: Kansas City, Mo. Amy Alcott 4,7,8 Trish Johnson 2,12,14,15,16,17 Age: 63 Ht.: 5’6 Helen Alfredsson 2,7,8,13,14,15,16 Cathy Johnston-Forbes 2,7,10,16 Home: Santa Monica, Calif. Danielle Ammaccapane 2,8,16 Rosie Jones 2,8.14,16 Donna Andrews 7,8 Lorie Kane 8,16 Turned Professional: 1975 Jean Bartholomew 9,16 Laurel Kean 2 Joined LPGA Tour: 1975 Laura Baugh 5 Judith Kyrinis 18 Nanci Bowen 7 Martha Leach 2,3 LPGA Tour Playoff Record: 4-5 Barb Bunkowsky 16 Jenni Lidback 7 JoAnne Carner 4,5,8 Marilyn Lovander 2,16 LPGA Tour Victories: 29 - 1975 USX Golf Classic; 1976 Kay Cockerill 5 Chrysler-Plymouth Classic, Colgate Far East Open; 1981 Jane Crafter 16 Alice Miller 7 Laura Davies 1,2,4,7,8,12, Barbara Moxness 2,10,16 Sarasota Classic; 1977 Houston Exchange Clubs Classic; 1978 13,14,15,16 Barb Mucha 2,8,16 American Defender; 1979 Elizabeth Arden Classic, du Maurier Alicia Dibos 2,16 Martha Nause 7,16 Classic, Crestar-Farm Fresh Classic, Mizuno Classic; 1980 Wendy Doolan 8,9,16 Liselotte Neumann 2,4,8,14,16,17 Cindy Figg-Currier 16 Michele Redman 2,8,14,15,16 American Defender, Mayflower Classic, U.S. -

La Solheim Cup 2023 Aterriza En España

Solheim Cup 2023 ¡La Solheim Cup aterriza en España! e ha hecho de rogar, pero el sueño la larga lista de grandes acontecimientos Un país apasionado por el golf satisfacción en nuestro país. Desde dirigentes impulsores del proyecto. Para su Director Solheim Cup ya es una realidad. de primer nivel desarrollados con éxito, El primer anuncio corrió a cargo de Alexandra a representantes políticos pasando por las General, Íñigo Aramburu, la clave del éxito ha Del 18 al 24 de S El campo malagueño de Finca desde los Juegos Olímpicos de Barcelona Armas, Directora Ejecutiva del Ladies European principales protagonistas, las jugadoras, todos sido “el buen entendimiento que ha habido “ Cortesín acogerá la edición 2023 de la 1992 a la Ryder Cup 1997. Tour, cuya exposición resume el sentir del han expresado su agrado en diferentes foros. entre todas las instituciones involucradas: septiembre de 2023, mejor competición golfística femenina No conviene olvidar que España posee organismo que dirige con acierto en esta Uno de ellos, Gonzaga Escauriaza, Presidente Andalucía, Costa del Sol, Acosol, el Ayuntamiento el campo malagueño de del 18 al 24 de septiembre de ese año. O un largo historial como país anfitrión de segunda etapa. “Estamos encantados de de la RFEG: “La celebración de la Solheim Cup de Marbella, el Ayuntamiento de Benahavis, la Finca Cortesín albergará lo que es lo mismo, por primera vez se pruebas de golf de alto nivel, más allá anunciar que España será el país organizador en nuestro país en 2023 es una magnífica RFEG y la RFGA, que han sabido trabajar al este espectacular evento podrá ver en España a las mejores jugadoras de la citada Ryder Cup: hasta 76 torneos de la Solheim Cup en 2023 cuando la noticia tanto para el deporte del golf como unísono para conseguir este hito que impulsará europeas y estadounidenses juntas en un entre el LET y el LET Access Series se han competición vuelva a suelo europeo con para el conjunto de la sociedad española. -

Success for the Sixes

SUCCESS FOR THE SIXES SEPTEMBER 2017 METHODOLOGY SMS INC. utilised their Sports Radar platform DATE DOMAIN COUNTRY to collect, code and analyse commentary around the Golf Sixes tournament in May at the Centurion Club. www.golfsixes.com Coding the data using the following criteria enabled us to look far beyond the noise AUTHOR/ SENTIMENT TOPICS being generated to understand sentiment AUTHOR TYPE in more detail and the key conclusions; ABOUT SMS INC. SPORTS MARKETING SURVEYS INC. is an commentary in real time. Sports Radar allows SMS experienced and focused sports research INC. to identify and interrogate the sentiment business servicing the sports event, sports & themes of the discussion whilst providing equipment, sport venue, sports federation and structure and meaning to this vast dataset. sports goods industry for over 30 years. Radar is a SaaS-based social and digital intelligence We provide SMART data, analysis and insight platform, efficiently delivering breadth and depth of for leading sports equipment manufacturers, coverage from a wide range of sources including; sports federations, major sports events, speciality retailers, and venue operators to enable • 85,000+ news sources, from over 200 countries our clients to understand more about their • Full Twitter firehose with 30 days of historical data customers, competitors and marketplace. • 2 million+ articles a day • 6,000+ social networks and 5,000+ forums Through Sports Radar, SMS INC. are able to meet the increasing desire in the sports industry • Customer chosen public URLs added as to gain intelligence and insight from online additional data sources www.sportsmarketingsurveysinc.com EXECUTIVE SUMMARY GolfSixes, a new fast-paced golf tournament The event, however, was not without hitches.