University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

285 Summer 2008 SFRA Editors a Publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg

285 Summer 2008 SFRA Editors A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 In This Issue [email protected] [email protected] SFRA Review Business Big Issue, Big Plans 2 SFRA Business Craig Jacobsen Looking Forward 2 English Department SFRA News 2 Mesa Community College Mary Kay Bray Award Introduction 6 1833 West Southern Ave. Mary Kay Bray Award Acceptance 6 Mesa, AZ 85202 Graduate Student Paper Award Introduction 6 [email protected] Graduate Student Paper Award Acceptance 7 [email protected] Pioneer Award Introduction 7 Pioneer Award Acceptance 7 Thomas D. Clareson Award Introduction 8 Managing Editor Thomas D. Clareson Award Acceptance 9 Janice M. Bogstad Pilgrim Award Introduction 10 McIntyre Library-CD Imagination Space: A Thank-You Letter to the SFRA 10 University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Nonfiction Book Reviews Heinlein’s Children 12 105 Garfield Ave. A Critical History of “Doctor Who” on Television 1 4 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 One Earth, One People 16 [email protected] SciFi in the Mind’s Eye 16 Dreams and Nightmares 17 Nonfiction Editor “Lilith” in a New Light 18 Cylons in America 19 Ed McKnight Serenity Found 19 113 Cannon Lane Pretend We’re Dead 21 Taylors, SC 29687 The Influence of Imagination 22 [email protected] Superheroes and Gods 22 Fiction Book Reviews SFWA European Hall of Fame 23 Fiction Editor Queen of Candesce and Pirate Sun 25 Edward Carmien The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories 26 29 Sterling Rd. Nano Comes to Clifford Falls: And Other Stories 27 Princeton, NJ 08540 Future Americas 28 [email protected] Stretto 29 Saturn’s Children 30 The Golden Volcano 31 Media Editor The Stone Gods 32 Ritch Calvin Null-A Continuum and Firstborn 33 16A Erland Rd. -

Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding Katharina M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding Katharina M. Freund University of Wollongong, [email protected] Recommended Citation Freund, Katharina M., "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3447 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] “Veni, Vidi, Vids!”: Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong by Katharina Freund (BA Hons) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications 2011 CERTIFICATION I, Katharina Freund, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Arts Faculty, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Katharina Freund 30 September, 2011 i ABSTRACT This thesis documents and analyses the contemporary community of (mostly) female fan video editors, known as vidders, through a triangulated, ethnographic study. It provides historical and contextual background for the development of the vidding community, and explores the role of agency among this specialised audience community. Utilising semiotic theory, it offers a theoretical language for understanding the structure and function of remix videos. -

Chapter Five Bibliographic Essay: Studying Star Trek

Jessamyn Neuhaus http://geekypedagogy.com @GeekyPedagogy January 2019 Chapter Five Bibliographic Essay: Studying Star Trek Supplement to Chapter Five, “Practice,” of Geeky Pedagogy: A Guide for Intellectuals, Introverts, and Nerds Who Want to Be Effective Teachers (Morgantown: University of West Virginia Press, 2019) In Chapter Five of Geeky Pedagogy, I argue that “for people who care about student learning, here’s the best and worst news about effective teaching that you will ever hear: no matter who you are or what you teach, you can get better with practice. Nothing will improve our teaching and increase our students’ learning more than doing it, year after year, term after term, class after class, day after day” (146). I also conclude the book with a brief review of the four pedagogical practices described in the previous chapters, and note that “the more time we can spend just doing them, the better we’ll get at effective teaching and advancing our students’ learning” (148). The citations in Chapter Five are not lengthy and the chapter does not raise the need for additional citations from the scholarship on teaching and learning. There is, however, one area of scholarship that I would like to add to this book as a nod to my favorite geeky popular text: Star Trek (ST). ST is by no means a perfect franchise or fandom, yet crucial to its longevity is its ability to evolve, most notably in terms of diversifying popular presentations. To my mind, “infinite diversity in infinite combinations” will always be the most poetic, truest description of both a lived reality as well as a sociocultural ideal—as a teacher, as a nerd, and as a human being. -

Shadow Highlander Ebook

SHADOW HIGHLANDER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Donna Grant | 368 pages | 14 Sep 2011 | St Martin's Press | 9780312533489 | English | New York, United States Shadow Highlander PDF Book Get A Copy. The result is a wonderfully dark, delightfully well-written tale. Jun 21, Joey Corr rated it it was amazing. Can't wait for the next one. Danger lurks at every turn as Dierdre launches new attacks against them. He is very reluctant to be with her because of his "gift" but he cannot fight the attraction any longer. User Ratings. Dawn's Desire. She has never left her village before and always does what she's told by the elders. MacLeod is tormented by visions of his own death, beheaded by a mysterious dark-hooded figure. Does he crave her because he touch her and not know her thoughts or is more? What Galen does not know, is that this beautiful druid is the artifact that they have been looking for. Paperback List Price: 7. But what he discovers is far more powerful—and far more dangerous. But Reaghan holds a secret power deep inside her that could destroy them both. Never once did I get bored, anticipating what would happened next and keeping me on my toes. And then there is Reaghan. Dark Sword 5 , Dark World 5. Edit page. I was so worried many times in this book! I am curious as to who this other Druid clan is, and I have a feeling Brenna may be the one to wind up with Logan. ToyotaCare for Mirai covers normal factory scheduled maintenance for three years or 35, miles, whichever comes first. -

Curt Magazin N/F/E

curt Magazin N/F/E #159 - - - NOVEMBER 2011 - - - WWW.CURT.DE curt‘s Vorwort / curt #159 DIESMAL WIE Es ist noch nicht lange her, da zwängte ich mich in das hautenge curt-eigene Superheldenkostüm. Ich presste meine vom Dancen ange- G IIVV BRUNSWICK!D schwollenen Füße in die maximal hässlichen Heldenturnschuhe von LA Gear (Modell „Michael Jackson“), Größe 38, schnürte meinen Ranzen G ER I M in das Muskelkorsett aus Schaumstoff, das mit seinen Schwammeigenschaften den übelstriechenden Schweiß meiner Vorgängerhelden GASTRO-BOWLINGASTRO-BOWLIN absorbierte (offensichtlich alles ungewaschene, nicht deodorierte Männer mit Hang zur körperlichen Verwahrlosung), spannte mir den lächerlichen Gürtel mit der Longhornrind-Schnalle um und band mir die „Augenmaske“ vor´s Gesicht. Fertig war der curtMän #91, also ich. VEMBER, 20H Schwitzend, stinkend, hässlich zog ich los, um curt als Marke zu präsentieren und zu pushen. In der U-Bahn, auf dem Weg in die Innen- MITTWOCH, 9. NO stadt, erregte ich keinerlei Aufmerksamkeit, da ich recht homogen in einer Masse untertauchte, die meinem Look & Feel ebenbürtig war. Das Flanieren durch die belebte KönigKaiserKarolinnenstraße empfand ich schon eher als unangenehm, wenn auch die Reaktionen der Passanten extrem unterschiedlich ausfielen: vom vergeilte Eiertätscheln bis zum erbosten Eiertreten, vom Zungenkuss bis zur Kopfnuss, vom Liebesschwur bis zur Mordandrohung widerfuhr mir hier alles mehrfach. Und das, obwohl ich noch ohne die üblichen Heldengesten und UND DU -plattitüden daher kam. Ich lief nur rum. Einfach so. Schon überlegte ich, meine Mission „Markensteigerung“ abzubrechen, da brannte plötzlich die Lorenzkirche lichterloh, die Flammen BIST DABEI drohten auf die umliegende Gebäude überzuspringen und eine Schneise der Verwüstung über´s Rathaus bis hin zur Kaiserburg zu schlagen. -

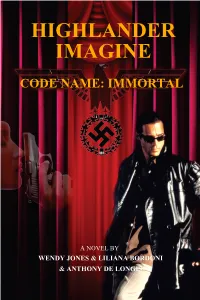

Code Name: Immortal

HIGHLANDER IMAGINE CODE NAME: IMMORTAL A NOVEL BY WENDY JONES & LILIANA BORDONI & ANTHONY DE LONGIS FICTION: ACTION & ADVENTURE/ROMANCE/HISTORICAL "This train can't take a Quickening, it will be destroyed! How many people will die because of us?" IT'S SPY VS SPY with Duncan MacLeod of the Clan MacLeod caught in the middle. When Connor suddenly disappears, Annelise’s desperate plea for Duncan to help her find him pulls the Highlander into a deadly game of cat and mouse. Soon, Duncan is face-to-face with the head of the Hunters’ organization and their darkest secrets. Master of the sword, Anthony De Longis weaves a deadly tale of suspense, intrigue and no-holds-barred sword fights between the Mac Leods and those seeking their Quickenings. This work was fully authorized by Davis-Panzer Productions and Studiocanal Films Ltd; however the content is wholly an RK Books original fan creation. “Since when do Immortals need an excuse to kill Watchers?” Annelise snapped. “It was just evening the score for what those people do to you people. I would’ve done the same,” she finished, coldly. Aghast, Duncan did a double take. “Kill Watchers—what are you saying? What score are you talking about?” “I know now who’s responsible for what happened to my brother,” she continued. “Connor promised he would help me free him—he’s on his way there now, but I know it’s a trap. You’ve got to help me, Duncan. Take me to Connor before it is too late for both of them.” Follow Solo Highlander Imagine Code Name: Immortal An RK Books production www.RK-books.com ISBN: 978-0-9777110-6-2 Copyright © January 4, 2018 by Wendy Lou Jones Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Jones, Wendy Lou Highlander Imagine: Code Name Immortal by Wendy Lou Jones Fiction: Historical │ Mystery Detective / Historical │ Romance / Action & Adventure Library of Congress Control Number: 2017963943 All rights reserved Highlander Imagine Series This work was fully authorized by Davis-Panzer Productions and Studiocanal Films Ltd; however the content is wholly an RK Books original fan creation. -

Controlling the Spreadability of the Japanese Fan Comic: Protective Practices in the Dōjinshi Community

. Volume 17, Issue 2 November 2020 Controlling the spreadability of the Japanese fan comic: Protective practices in the dōjinshi community Katharina Hülsmann, Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf, Germany Abstract: This article examines the practices of Japanese fan artists to navigate the visibility of their own works within the infrastructure of dōjinshi (amateur comic) culture and their effects on the potential spreadability of this form of fan comic in a transcultural context (Chin and Morimoto 2013). Beyond the vast market for commercially published graphic narratives (manga) in Japan lies a still expanding and particularizing market for amateur publications, which are primarily exchanged in printed form at specialized events and not digitally over the internet. Most of the works exchanged at these gatherings make use of scenarios and characters from commercially published media, such as manga, anime, games, movies or television series, and can be classified as fan works, poaching from media franchises and offering a vehicle for creative expression. The fan artists publish their works by making use of the infrastructure provided by specialized events, bookstores and online printing services (as described in detail by Noppe 2014), without the involvement of a publishing company and without the consent of copyright holders. In turn, this puts the artists at risk of legal action, especially when their works are referring to the content owned by notoriously strict copyright holders such as The Walt Disney Company, which has acquired Marvel Comics a decade ago. Based on an ethnographic case study of Japanese fan artists who create fan works of western source materials (the most popular during the observed timeframe being The Marvel Cinematic Universe), the article identifies different tactics used by dōjinshi artists to ensure their works achieve a high degree of visibility amongst their target audience of other fans and avoid attracting the attention of casual audiences or copyright holders. -

School Calendar Unchanged President Camala King Will Present Ter of Mr

No charges filed Crofton man dies %■ Devoted to the best interest of Cadiz ond Trigg County from gun wound VOLUME 101 NUMBER 19 THURSDAY, MAY 13, 1982 ONE SECTION, 14 PAGES PRICE 20 CENTS The shooting death of a Crofton The woman, who was not man in Trigg County Saturday identified, then drove to her uncle’s night may be ruled as justifiable home, a short distance away and homicide when the case is present Knight walked to the subdivision ed to the Grand Jury, according to and, upon entering the mobile County Attorney Ken Kennedy. home, became violent and began to ; ■ ' f , Wendell Harold Knight, 21, was use abusive language, but eventual pronounced dead at the scene by ly left, Oakley said. County Coroner John Vinson after Then about 11 p.m., Knight he had been shot following what returned and was allegedly shot by was described as a domestic argu the woman’s uncle, Noble Harris, ment. The shooting took place 42, of Nortonville. inside a mobile home in Heather Kennedy said Knight had '•**.......... *\ Hills Subdivision, about 12 miles threatened to “ break her neck” , west of Cadiz. referring to the girl friend. He w ‘m m Vinson said Knight was shot at added that the investigating officer close range with a .38 caliber pistol. had learned that recently Knight He added that the results of an was alleged to have shot the head autopsy conducted in Hopkinsville lights out of a car in which the by Dr. Frank Pitzer had not been woman was sitting. completed. County Sheriff Ken No charges have been filed Oakley said Knight was shot once in against Harris, Kennedy said, since the chest. -

Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael: the Duel for the Soul of American Film Criticism

1 Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael: The Duel For the Soul of American Film Criticism By Inge Fossen Høgskolen i Lillehammer / Lillehammer University College Avdeling for TV-utdanning og Filmvitenskap / Department of Television and Film Studies (TVF) Spring 2009 1 2 For My Parents 2 3 ”When we think about art and how it is thought about […] we refer both to the practice of art and the deliberations of criticism.” ―Charles Harrison & Paul Wood “[H]abits of liking and disliking are lodged in the mind.” ―Bernard Berenson “The motion picture is unique […] it is the one medium of expression where America has influenced the rest of the world” ―Iris Barry “[I]f you want to practice something that isn’t a mass art, heaven knows there are plenty of other ways of expressing yourself.” ―Jean Renoir “If it's all in the script, why shoot the film?” ―Nicholas Ray “Author + Subject = Work” ―Andrè Bazin 3 4 Table of Contents Preface and Acknowledgements p. 6. Introduction p. 8. Defining Art in Relation to Criticism p. 14. The Popular As a Common Ground– And an Outline of Study p. 19. Career Overview – Andrew Sarris p. 29. Career Overview – Pauline Kael p. 32. American Film Criticism From its Beginnings to the 1950s – And a Note on Present Challenges p. 35. Notes on Axiological Criticism, With Sarris and Kael as Examples p. 41. Movies: The Desperate Art p. 72. Auteurism – French and American p. 82. Notes on the Auteur Theory 1962 p. 87. "Circles and Squares: Joys and Sarris" – Kael's Rebuttal p. 93. -

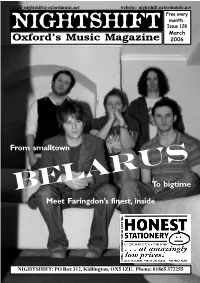

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 128 March Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 From smalltown belarusTo bigtime Meet Faringdon’s finest, inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] LOCAL BANDS have until March 15th to City Girl. This year’s line-up will be announced submit demos for this year’s Oxford Punt. The on the Nightshift website noticeboard and on Punt, organised by Nightshift Magazine, takes Oxfordbands.com on March 16th. place across six venues in Oxford city centre on All-venue Punt passes are now on sale from Wednesday 10th May and will showcase 18 of Polar Bear Records on Cowley Road or online the best new unsigned bands and artists in the from oxfordmusic.net. As ever there will only county. Bands and solo acts can send demos, be 100 passes available, priced at £7 each (plus clearly marked The Punt, to Nightshift, PO Box booking fee). 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Bands who have previously made their reputations early on at TRUCK FESTIVAL 2006 tickets are now on the Punt include The Young Knives and Fell sale nationally after being made available to Oxfordshire music fans only at the start of STEVE GORE February. Tickets for the two-day festival at Hill Farm, Steventon over the weekend of the GARY NUMAN plays his first Oxford show 1965-2006 22nd and 23rd July are priced at £40 and are on for 12 years when he appears at Brookes th Steve Gore, bass player with local ska-punk sale from the Zodiac box office, Polar Bear University Union on Sunday 30 April. -

Highlander the Immortals

Highlander The Immortals 1 Rules Kevin Webb http://tv.groups.yahoo.com/group/highlanderd20/ Art Alexander Winston http://stonecrowdesign.deviantart.com/ April Dwiggins http://aprildwiggins.com/blog/ Scott Vincent http://tv.groups.yahoo.com/group/highlanderd20/ Highlander Official Highlander Message Board - http://www.highlander-community.com/Forum/ OGL/SRD Wizards - http://www.wizards.com/default.asp?x=d20/article/srdarchive Pathfinder - http://paizo.com/pathfinderRPG/prd/ 2 Quickening Lace .......................................... 17 Contents The Game ........................................................... 5 Quickening Luck ......................................... 17 Templates ........................................................... 6 Quickening Magic ....................................... 18 Creating an Immortal ..................................... 6 Quickening Pain .......................................... 18 Creating a Watcher ........................................ 8 Quickening Weapon .................................... 18 Immortal Skills................................................. 10 The Beast ..................................................... 19 Knowledge: Immortals ................................. 10 Weapon Bond .............................................. 19 Knowledge: Watcher ................................... 11 Quickening....................................................... 20 Quickening ................................................... 11 Description.................................................. -

Metalepsis in Fan Vids and Fan Fiction Tisha Turk

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well English Publications Faculty and Staff choS larship 2011 Metalepsis in Fan Vids and Fan Fiction Tisha Turk Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/eng_facpubs Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Definitive version available in Metalepsis in Popular Culture, eds. Karin Kukkonen and Sonia Klimek. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. 2011. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff choS larship at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TISHA TURK (University of Minnesota, Morris) Metalepsis in Fan Vids and Fan Fiction In the decades since Gérard Genette coined the term, narrative metalepsis has generally been understood as a merging of diegetic levels, a narrative phenomenon that destabilizes, however provisionally, the distinction be- tween reality and fiction. As discussed by Genette, this formulation as- sumes a certain degree of stability outside the text itself: narratees may become narrators and vice versa, but authors remain authors and readers remain readers.1 In the context of novels and films, such an assumption is not unreasonable. But with the advent of what has been called ‗participa- tory‘ or ‗read/write culture‘ (Jenkins 1992; Lessig 2004), in which au- diences become authors and textual boundaries become increasingly por- ous, we must consider how both the nature and the effects of metalepsis may be affected by these changes.