Cartoon Violence and Aggression in Youth ⁎ Steven J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

Captain America

The Star-spangled Avenger Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Captain America first appeared in Captain America Comics #1 (Cover dated March 1941), from Marvel Comics' 1940s predecessor, Timely Comics, and was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. For nearly all of the character's publication history, Captain America was the alter ego of Steve Rogers , a frail young man who was enhanced to the peak of human perfection by an experimental serum in order to aid the United States war effort. Captain America wears a costume that bears an American flag motif, and is armed with an indestructible shield that can be thrown as a weapon. An intentionally patriotic creation who was often depicted fighting the Axis powers. Captain America was Timely Comics' most popular character during the wartime period. After the war ended, the character's popularity waned and he disappeared by the 1950s aside from an ill-fated revival in 1953. Captain America was reintroduced during the Silver Age of comics when he was revived from suspended animation by the superhero team the Avengers in The Avengers #4 (March 1964). Since then, Captain America has often led the team, as well as starring in his own series. Captain America was the first Marvel Comics character adapted into another medium with the release of the 1944 movie serial Captain America . Since then, the character has been featured in several other films and television series, including Chris Evans in 2011’s Captain America and The Avengers in 2012. The creation of Captain America In 1940, writer Joe Simon conceived the idea for Captain America and made a sketch of the character in costume. -

EM Phantoms Flyer

Experimental Human Phantoms EM-Phantoms Precision Phantoms for OTA, SAR, MRI Evaluations and RF Transceiver Optimization What are EM-Phantoms? SPEAG’s EM phantoms are high-quality body-body transmitters in any plausible anthropomorphically shaped phantoms usage situation. Head and hand phan- designed for evaluation of OTA, SAR, toms compatible with current standard and MRI performance and on-body and specifications provide accurate and re- implant transceiver optimization. The producible OTA testing of wireless de- flexible whole-body phantom POPEYE vices. Customized phantoms are also with its posable arms, legs, hands and available on request, e.g., ears, hands feet enables testing of handheld and with custom grips, etc. MADE SWISS EM-Phantoms Optimized for OTA, SAR, MRI Evaluations Posable Whole-Body Phantom POPEYE V5.x · Simulates realistic human postures for OTA, SAR, and MRI evaluations · Dimensions meet requirements for conservative testing · Stand for support and transportation available · Consists of torso with head, left/right arms with hands and left/right legs with feet Torso Phantom · Shape: Anthropomorphic (glass-fi ber-reinforced epoxy) · Shell thickness: 2 ± 0.2 mm in the ear-mouth region & 3 ± 1 mm in other regions · Head: SAM according to the IEEE SCC 34, 3 GPP, and CTIA standards MRI-safety evaluation suite: Torso phantom and EASY4MRI · Filling volume: 28 liters · TORSO OTA V5.1: fi lled with gel material (CTIA compliant) · TORSO SAR V5.1: empty torso for SAR measurements; custom- defi ned cuts available on request · -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature

Brown, Noel. " An Interview with Steve Segal." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 197–214. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-013>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 03:24 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 97 Chapter 13 A N INTERVIEW WITH STEVE SEGAL N o e l B r o w n Production histories of Toy Story tend to focus on ‘big names’ such as John Lasseter and Pete Docter. In this book, we also want to convey a sense of the animator’s place in the making of the fi lm and their perspective on what hap- pened, along with their professional journey leading up to that point. Steve Segal was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1949. He made his fi rst animated fi lms as a high school student before studying Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he continued to produce award- winning, independent ani- mated shorts. Aft er graduating, Segal opened a traditional animation studio in Richmond, making commercials and educational fi lms for ten years. Aft er completing the cult animated fi lm Futuropolis (1984), which he co- directed with Phil Trumbo, Segal moved to Hollywood and became interested in com- puter animation. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

A Player's Guide Part 1

A Player’s Guide Effective: 9/20/2010 Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2010 Core Rulebook Part 1 – Clarifications Section 1: Rulebook 3 Section 2: Powers and Abilities 5 Section 3: Abilities 9 Section 4: Characters and Special Powers 11 Section 5: Special Characters 19 Section 6: Team Abilities 21 Section 7: Alternate Team Abilities 23 Section 8: Objects 25 Section 9: Maps 27 Part 2 – Current Wordings Section 10: Powers 29 Section 11: Abilities 33 Section 12: Characters and Special Powers 35 Section 13: Team Abilities 71 Section 14: Alternate Team Abilities 75 Section 15: Objects 77 Section 16: Maps 79 How To Use This Document This document is divided into two parts. The first part details every clarification that has been made in Heroclix for all game elements. These 40 pages are the minimal requirements for being up to date on all Heroclix rulings. Part two is a reference guide for players and judges who often need to know the latest text of any given game element. Any modification listed in part two is also listed in part one; however, in part two the modifications will be shown as fully completed elements of game text. [This page is intentionally left blank] Section 1 Rulebook at the time that the player gives the character an action or General otherwise uses the feat.‖ Characters that are removed from the battle map and placed Many figures have been published with rules detailing their on feat cards are not affected by Battlefield Conditions. -

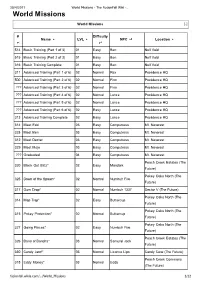

World Missions - the Fusionfall Wiki -… World Missions

20/4/2011 World Missions - The FusionFall Wiki -… World Missions World Missions [-] # Difficulty Name LVL NPC Location 514 Basic Training (Part 1 of 3) 01 Easy Ben Null Void 515 Basic Training (Part 2 of 3) 01 Easy Ben Null Void 316 Basic Training Complete 01 Easy Ben Null Void 311 Advanced Training (Part 1 of 6) 02 Normal Rex Providence HQ 500 Advanced Training (Part 2 of 6) 02 Normal Finn Providence HQ ??? Advanced Training (Part 3 of 6) 02 Normal Finn Providence HQ ??? Advanced Training (Part 4 of 6) 02 Normal Lance Providence HQ ??? Advanced Training (Part 5 of 6) 02 Normal Lance Providence HQ ??? Advanced Training (Part 6 of 6) 02 Easy Lance Providence HQ 313 Advanced Training Complete 02 Easy Lance Providence HQ 314 Meet Edd 03 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest 328 Meet Ben 03 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest 312 Meet Dexter 03 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest 329 Meet Mojo 03 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest ??? Graduated 04 Easy Computress Mt. Neverest Peach Creek Estates (The 320 Black Out Blitz* 02 Easy Mandark Future) Pokey Oaks North (The 325 Dawn of the Spawn* 02 Normal Numbuh Five Future) 317 Gum Drop* 02 Normal Numbuh 1337 Sector V (The Future) Pokey Oaks North (The 314 Map Trap* 02 Easy Buttercup Future) Pokey Oaks North (The 315 Pokey Protection* 02 Normal Buttercup Future) Pokey Oaks North (The 327 Going Places* 02 Easy Numbuh Five Future) Peach Creek Estates (The 326 Band of Bandits* 03 Normal Samurai Jack Future) 330 Candy Jarrr!* 03 Normal Licorice Lips Candy Cove (The Future) Peach Creek Commons 318 Eddy Money* 03 Normal Eddy (The -

French Animation History Ebook

FRENCH ANIMATION HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Neupert | 224 pages | 03 Mar 2014 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118798768 | English | New York, United States French Animation History PDF Book Messmer directed and animated more than Felix cartoons in the years through This article needs additional citations for verification. The Betty Boop cartoons were stripped of sexual innuendo and her skimpy dresses, and she became more family-friendly. A French-language version was released in Mittens the railway cat blissfully wanders around a model train set. Mat marked it as to-read Sep 05, Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. In , Max Fleischer invented the rotoscope patented in to streamline the frame-by-frame copying process - it was a device used to overlay drawings on live-action film. First Animated Feature: The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed , Germ. Books 10 Acclaimed French-Canadian Writers. Rating details. Dave and Max Fleischer, in an agreement with Paramount and DC Comics, also produced a series of seventeen expensive Superman cartoons in the early s. Box Office Mojo. The songs in the series ranged from contemporary tunes to old-time favorites. He goes with his fox terrier Milou to the waterfront to look for a story, and finds an old merchant ship named the Karaboudjan. The Fleischers launched a new series from to called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Annex 2: Providers Required to Respond (Red Indicates Those Who Did Not Respond Within the Required Timeframe)

Video on demand access services report 2016 Annex 2: Providers required to respond (red indicates those who did not respond within the required timeframe) Provider Service(s) AETN UK A&E Networks UK Channel 4 Television Corp All4 Amazon Instant Video Amazon Instant Video AMC Networks Programme AMC Channel Services Ltd AMC Networks International AMC/MGM/Extreme Sports Channels Broadcasting Ltd AXN Northern Europe Ltd ANIMAX (Germany) Arsenal Broadband Ltd Arsenal Player Tinizine Ltd Azoomee Barcroft TV (Barcroft Media) Barcroft TV Bay TV Liverpool Ltd Bay TV Liverpool BBC Worldwide Ltd BBC Worldwide British Film Institute BFI Player Blinkbox Entertainment Ltd BlinkBox British Sign Language Broadcasting BSL Zone Player Trust BT PLC BT TV (BT Vision, BT Sport) Cambridge TV Productions Ltd Cambridge TV Turner Broadcasting System Cartoon Network, Boomerang, Cartoonito, CNN, Europe Ltd Adult Swim, TNT, Boing, TCM Cinema CBS AMC Networks EMEA CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership CBS Europe CBS AMC Networks UK CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership Horror Channel Estuary TV CIC Ltd Channel 7 Chelsea Football Club Chelsea TV Online LocalBuzz Media Networks chizwickbuzz.net Chrominance Television Chrominance Television Cirkus Ltd Cirkus Classical TV Ltd Classical TV Paramount UK Partnership Comedy Central Community Channel Community Channel Curzon Cinemas Ltd Curzon Home Cinema Channel 5 Broadcasting Ltd Demand5 Digitaltheatre.com Ltd www.digitaltheatre.com Discovery Corporate Services Discovery Services Play