The Gender Fluidity of Krazy Kat, Gabrielle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EM Phantoms Flyer

Experimental Human Phantoms EM-Phantoms Precision Phantoms for OTA, SAR, MRI Evaluations and RF Transceiver Optimization What are EM-Phantoms? SPEAG’s EM phantoms are high-quality body-body transmitters in any plausible anthropomorphically shaped phantoms usage situation. Head and hand phan- designed for evaluation of OTA, SAR, toms compatible with current standard and MRI performance and on-body and specifications provide accurate and re- implant transceiver optimization. The producible OTA testing of wireless de- flexible whole-body phantom POPEYE vices. Customized phantoms are also with its posable arms, legs, hands and available on request, e.g., ears, hands feet enables testing of handheld and with custom grips, etc. MADE SWISS EM-Phantoms Optimized for OTA, SAR, MRI Evaluations Posable Whole-Body Phantom POPEYE V5.x · Simulates realistic human postures for OTA, SAR, and MRI evaluations · Dimensions meet requirements for conservative testing · Stand for support and transportation available · Consists of torso with head, left/right arms with hands and left/right legs with feet Torso Phantom · Shape: Anthropomorphic (glass-fi ber-reinforced epoxy) · Shell thickness: 2 ± 0.2 mm in the ear-mouth region & 3 ± 1 mm in other regions · Head: SAM according to the IEEE SCC 34, 3 GPP, and CTIA standards MRI-safety evaluation suite: Torso phantom and EASY4MRI · Filling volume: 28 liters · TORSO OTA V5.1: fi lled with gel material (CTIA compliant) · TORSO SAR V5.1: empty torso for SAR measurements; custom- defi ned cuts available on request · -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

How the Spinach, Popeye and Iron Decimal Point Error Myth Was Finally

Published by HealthWatch www.healthwatch-uk.org How the spinach, Popeye and iron decimal point error myth was finally bust CIBeT? (Can It Be True?) was the name coined by past HealthWatch chairman Professor John Garrow for an occasional series in this newsletter, in which an expert scrutinised popular myths. Who better to revive it, than supermythbuster Mike Sutton, who reveals the history of the legend of why spinach made Popeye so strong—and why Popeye was right all along, but not in the way we thought ... NE OF THE MOST complex and convoluted myths in the world of nutrition is the one called, for want of a less complex name, the ‘Spinach, Popeye and Iron Decimal Point Error Myth’. I discovered that the myth was started by the nutrition expert, Professor Arnold Bender (the late father of HealthWatch Secretary David Bender) in his inaugural lecture at the UOniversity of London in 1972. 1 The myth, once begun, was long popularised and eventually was veracious. came to be attributed to Professor Terence Hamblin, after he wrote The truth behind Bender’s and Hamblin’s decimal error knowl - in the British Medical Journal 2 in 1981: edge gap filling myth for why people think spinach is a good source “A statue of Popeye in Crystal City, Texas, commemorates the of iron when it isn’t, is that spinach contains no more iron than fact that singlehandedly he raised the consumption of Spinach by many other vegetables, such as lettuce for example. The fact of the 33%. America was ‘strong to the finish ‘cos they ate their spinach’ matter is that spinach is not a good source of nutritional iron, and duly defeated the Hun. -

Cartooning America: the Fleischer Brothers Story

NEH Application Cover Sheet (TR-261087) Media Projects Production PROJECT DIRECTOR Ms. Kathryn Pierce Dietz E-mail: [email protected] Executive Producer and Project Director Phone: 781-956-2212 338 Rosemary Street Fax: Needham, MA 02494-3257 USA Field of expertise: Philosophy, General INSTITUTION Filmmakers Collaborative, Inc. Melrose, MA 02176-3933 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story Grant period: From 2018-09-03 to 2019-04-19 Project field(s): U.S. History; Film History and Criticism; Media Studies Description of project: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story is a 60-minute film about a family of artists and inventors who revolutionized animation and created some of the funniest and most irreverent cartoon characters of all time. They began working in the early 1900s, at the same time as Walt Disney, but while Disney went on to become a household name, the Fleischers are barely remembered. Our film will change this, introducing a wide national audience to a family of brothers – Max, Dave, Lou, Joe, and Charlie – who created Fleischer Studios and a roster of animated characters who reflected the rough and tumble sensibilities of their own Jewish immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. “The Fleischer story involves the glory of American Jazz culture, union brawls on Broadway, gangsters, sex, and southern segregation,” says advisor Tom Sito. Advisor Jerry Beck adds, “It is a story of rags to riches – and then back to rags – leaving a legacy of iconic cinema and evergreen entertainment.” BUDGET Outright Request 600,000.00 Cost Sharing 90,000.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 690,000.00 Total NEH 600,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

David Hare, Surrealism, and the Comics Mona Hadler Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center, CUNY

93 David Hare, Surrealism, and the Comics Mona Hadler Brooklyn College and The Graduate Center, CUNY The history of the comic book in the United States has been closely allied with mass culture debates ranging from Clement Greenberg’s 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” to Fredric Wertham’s attack on the comic book industry in his now infamous 1954 book, Seduction of the Innocent. An alternative history can be constructed, however, by linking the comics to the expatriate Surrealist community in New York in the thirties and early forties with its focus on fantasy, dark humor, the poetics and ethics of evil, transgressive and carnivalesque body images, and restless desire. Surrealist artists are well known for their fascination with black humor, pulp fi ction, and crime novels—in particular the popular series Fantômas. Indeed, the image of the scoundrel in elegant attire holding a bloody dagger, featured in the writings of the Surrealist Robert Desnos (Color Plate 10), epitomized this darkling humor (Desnos 377-79).1 Pictures of Fantômas and articles on the pulp market peppered the pages of Surrealist magazines in Europe and America, from Documents in France (1929-1930) to VVV and View in New York in the early forties. By moving the discussion of the comics away from a Greenbergian or Frankfurt school discourse on mass culture to the debates surrounding Surrealism, other issues come to the fore. The comics become a site for the exploration of mystery, the imagination, criminality, and freedom. The comic book industry originated in the United States in the late thirties and early forties on the heels of a booming pulp fi ction market. -

POPEYE Hy Eisman

POPEYE Hy Eisman Opening Reception: Friday, October 9, 2015: 6-8 pm On View: October 2- October 31, 2015 Van Der Plas Gallery is pleased to announce “Popeye”, the first exhibition in history to display the original works of Popeye by the iconoclast Hy Eisman. The show will feature his original comic strip illustrations from the years 2008 to 2012. About the Artist: Hy Eisman was born March 27, 1927, in Paterson, N.J. He began his career when he created a comic strip for his high school newspaper. After a brief stint in the military, Eisman worked as ghost artist for the popular Kerry Drake comic strip. He soon turned his pen to the comic-book industry, drawing for various publishers of such titles as Nancy, The Munsters, Tom and Jerry and Little Lulu. Eisman's career as a cartoonist took off in 1967, when he started to draw Little Iodine. He really brought the adventures of the bratty, pony-tailed Iodine to life. He left that strip in 1986 to chronicle the adventures of those two more-famous brats, The Katzenjammer Kids, the world's oldest continuing comic strip. In 1994, Eisman added another comic legend to his repertoire when he started drawing the Sunday Popeye strip, which stars Popeye, the salty sailor man, and his crew of lovable co-stars Olive Oyl, Swee' Pea, Wimpy and Bluto who were created by E.C. Segar for his comic strip Thimble Theatre in 1919. Popeye made his first appearance in 1929. He was an instant sensation who would go on to star in hundreds of cartoons, comic books, his own radio show and even a live-action feature film starring Robin Williams. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Sergio Aragonés Marginalizes Francoism in the Exile Newspaper España Libre (NYC)

Camino Real 7: 10. (2015): 129-146 Sergio Aragonés Marginalizes Francoism in the Exile Newspaper España Libre (NYC) MONTSE FEU Abstract Sergio Aragonés is an award-winning and celebrated Mad Magazine cartoonist whose prolific career includes his bestselling comicsGroo the Wanderer and Boogeyman, among others. However, his anti-Francoist cartoons published in the exile newspaper España Libre (1939-1977, NYC) have not been studied. Using an interdisciplinary theoretical approach to humor, I examine the social function of selected cartoons by Aragonés. The drawings, published from 1962 to 1965, exposed the political persecution exerted by Francisco Franco to a global readership. His front- page cartoons also informed and emotionally sustained the dissenting working-class resistance under the regime and abroad. Keywords: Spaniards in the United States, Spanish Civil War, Exile Newspapers, cartoons, Labor Resistance Movements, Francisco Franco’s Dictatorship. Maria Montserrat Feu López (Montse Feu), Assistant Professor in Spanish at Sam Houston State University. She has published about the Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas and their newspaper España Libre (NYC 1939- 1977). Feu López, M. M. “Sergio Aragonés “Marginalizes” Francoism in The Exile Newspaper España Libre (New York City)”. Camino Real, 7:10. Alcalá de Henares: Instituto Franklin – UAH, 2015: 127-144. Print. Recibido: 1/12/2014; 2ª versión 26/1/2015. 129 Camino Real Resumen Sergio Aragonés es uno de los humoristas gráficos más conocidos de la revista norteamericana Mad. Su prolífica y premiada carrera incluye sus populares cómics Groo the Wanderer and Boogeyman, entre otros muchos. Sin embargo, sus caricaturas antifranquistas publicadas en el periódico de exilio España Libre (1939-1977, Nueva York) no se han estudiado. -

IHS™ Jane's® Weapons

IHS™ Jane’s® Weapons Air-Launched 2014-2015 RobertHewson ISBN 978 07106 3104 6-Weapons Air-Launched ISBN 978 07106 3108 4-Weapons Ammunition ISBN 978 07106 3105 3-Weapons Infantry ISBN 978 07106 3106 0-Weapons Naval ISBN 978 07106 3107 7-Weapons Strategic ISBN 978 07106 3120 6-Weapons Full Set ©2014 IHS. All rights reserved. Thirdparty details and websites No partofthis publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any Any thirdparty details and websites aregiven for information and reference purposes means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or be stored in only and IHS Global Limited does not control, approve or endorse these thirdparties any retrieval system of any nature, without prior written permission of IHS Global or thirdparty websites. Further,IHS Global Limited does not control or guarantee the Limited. Applications for written permission should be directed to Christopher Bridge. accuracy, relevance, availability, timeliness or completeness of the information contained on any thirdparty website. Inclusion of any thirdparty details or websites is Any views or opinions expressed by contributors and thirdparties arepersonal to not intended to reflect their importance, nor is it intended to endorse any views them and do not represent the views or opinions of IHS Global Limited, its affiliates or expressed, products or services offered, nor the companies or organisations in staff. question. Youaccess any thirdparty websites solely at your own risk. Disclaimer of liability Use of data Whilst -

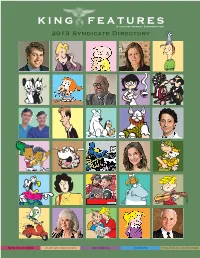

2013 Syndicate Directory

2013 Syndicate Directory NEW FEATURES CUSTOM SERVICES EDITORIAL COMICS POLITICAL CARTOONS What’s New in 2013 by Norman Feuti Meet Gil. He’s a bit of an underdog. He’s a little on the chubby side. He doesn’t have the newest toys or live in a fancy house. His parents are split up – his single mother supports them with her factory job income and his father isn’t around as often as a father ought to be. Gil is a realistic and funny look at life through the eyes of a young boy growing up under circumstances that are familiar to millions of American families. And cartoonist Norm Feuti expertly crafts Gil’s world in a way that gives us all a good chuckle. D&S From the masterminds behind Mobilewalla, the search, discovery and analytics engine for mobile apps, comes a syndicated weekly column offering readers both ratings and descriptions of highly ranked, similarly themed apps. Each week, news subscribers receive a column titled “Fastest Moving Apps of the Week,” which is the weekly hot list of the apps experiencing the most dramatic increases in popularity. Two additional “Weekly Category” features, pegged to relevant news, events, holidays and calendars, are also available. 3TW Drs. Oz and Roizen give readers quick access to practical advice on how to prevent and combat conditions that affect overall wellness and quality of life. Their robust editorial pack- age, which includes Daily Tips, a Weekly Feature and a Q & A column, covers a wide variety of topics, such as diet, exercise, weight loss, sleep and much more. -

Conversation with Lee Falk

CONVERSATION WITH LEE FALK While still an undergraduate in the Midwest, Lee Falk invented Mandrake the Magician, the first black and white crime-fighting team. He created The Phantom, the first superhero in tights, within two years of graduation. F alk's other consuming passion was theater, which he indulged by owning and operating several playhouses, where he often filled the roles of producer and /or director. Raymond Elman: You've written sev- a rather ungracious young man, who talked became my partner, was a Harvard graduate, eral plays, owned a number of theaters, like he had mashed potatoes in his mouth and he knew about a theater in Cambridge- and produced many significant theater - very Eastern Establishment. He said, the Brattle Theater. A little group called pieces. Was your theater life a whole "These little midwest kind of stories are The Straw Hat Theater played there, run separate existence from your comic strip very boring. I don't think you should try to by Catherine Huntington, who dropped world? write." About five years later I was sail- the Straw Hat group to run the Provincetown Lee Falk: My ambition when I was a ing backfromEuropeon the Isle de France. Theater Company. Oddly enough, these young man was to be a playwright. I wrote By that time I had two strips going, I had two Huntingtons weren't related. His real plays and acted while I was in college, started a theater, I had a beautiful young name was Duryea Huntington Jones. He though I was never comfortable on the wife, and for a young man I was very changed his name because the boys at stage. -

Comics Lovers Will Be Drawn to Ohio Museum

LIFESTYLE TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 2013 Features36 Comics lovers will be drawn to Ohio museum Photo shows the cover File photo shows a of the New York Journal comic called “Ho- from Oct 18, 1896 in gan’s Alley” by Columbus, Ohio. Richard F Outcault Juli Slemmons holds a “Calvin and Hobbes” comic by cartoonist Bill Watterson from Oct 18, 1896 in Jeremy Stone frames a Billy Ireland comic strip from Dec 11, 1921 called “The at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. Columbus, Ohio.—AP Passing Show” at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. photos here is a place where Snoopy frolics carefree with the scandalous says current curator Jenny Robb, noting that for many years original comic “I told my father, this is what we’ve all be working for for 30 years,” says Yellow Kid, where Pogo the possum philosophizes alongside Calvin strips were just thrown out with the trash and animation celluloid sheets — Brian Walker, who has written or contributed to three dozen books on the Tand Hobbes. It’s a place where Beetle Bailey loafs with Garfield the known as “cels” — were routinely wiped clean and reused. history of comics. “It’s kind of like the ultimate dream that we hoped would cat, while Krazy Kat takes another brick to the noggin, and brooding heroes Today, the museum collection includes more than 300,000 original strips happen someday, where all this great artwork is being kept safely and battle dark forces on the pages of fat graphic novels. That doesn’t even be- from everybody who’s anybody in the newspaper comics world, plus 45,000 archived and made accessible to the public.” gin to describe everything that’s going on behind the walls of the new Billy books, 29,000 comic books and 2,400 boxes of manuscript material, fan It’s partly because of the Walkers that the museum is what it is today.