A Phenomenological Study Into Niche Marketing in Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Shoes... Page 3

Brought to you by Publishers of The Your Valley Source & The Promised Land FREE TAKE ONE The Western Slope’s Guide to Entertainment, Arts & News for May 2012 Women and Shoes... Page 3 Catching up with Cody Gay Page 13 Desert Rocks Festival Page 9 GRAND JUNCTION Test Drive the All New 2012 Jeep Compass CHRYSLER • JEEP • DODGE 2578 HWY 6 & 50 Grand Junction (on the corner of motor & funny little street) 245-3100 • 1-800-645-5886 THE EVOLUTION OF A TRULY LEGENDARY BLOODLINE www.grandjunctionchrysler.com • Sales: Mon-Fri 8:30-6:00, Sat 8:30-5:00 • Parts and Service: Mon - Fri 7:30-5:30, Sat 9:00-1:00 / Closed on Sundays Largest Lighting Showroom in Western Colorado 10,000 sq ft of Lighting • Accessories The SOURCE Tiffany Lamps • Led Flowers • Fountains Over 100 manufacturers FREE Residential Lighting Design Certified Lighting Designers Save up to 50% New Construction & Contractor Discounts New Products Arrive Daily! Not Just a Lighting Showroom Mirrors • Candle Holders • Plate Racks • Lamps Lamp Shades • Clocks • Vases • Flowers • Pictures Tables • Chairs • Wine Racks Final Countdown Bonus rebates of up to an EXTRA WE ARE AN XCEL ENERGY ALLY PARTNER! 30% for T12 upgrades • Let One Source Lighting do all of the leg work from April 1 to December 31, 2012* to receive lighting rebates! 2 • Xcel Energy Will Pay Up To 50% of your project! We have the Only Lighting Efficiency Professional Certification in the Grand Junction Area. Don’t forget for all of your commercial lighting needs. Ask about our FREE Commercial Lighting Energy Audit. -

'T: Ottawa

csf 001 TOWARD A HUMANISTIC-TRANSPERSONAL PSYCHOLOGY OF RELIGION by Peter A. Campbell Thesis presented to the Department of Religious Studies of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ^ «<o% BIBUOTHEQUES * ^^BlBi; 'T: Ottawa LlBRAKicS \ Vsily oi <P Ottawa, Canada, 1972 Peter A. Campbell, Ottawa 1972. UMI Number: DC53628 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53628 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Jean-Marie Beniskos, Ph.D., of the Faculty of Education, University of Ottawa, for his helpful direction of this dissertation. My heartfelt thanks are also due to Edwin M. McMahon, my close collabora tor and companion whose constructive criticism and steady encouragement have been a continued source of support through out this research project. CURRICULUM STUDIORUM Peter A. Campbell was born January 21, 1935, in San Francisco, California. He received the Bachelor of Arts degree in 1957 and the Master of Arts degree and Licentiate in Philosophy in 1959 from Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington. -

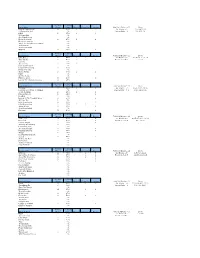

Up to Here # Times Played % Shows Played Opened Closed Set Encore

# Times % Shows Up To Here Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Blow at High Dough 9 60% 2 3 Set Blocks = 6 1,5,7,9,12,14 I'll Believe In You 0% Encore Sets = 5 2,6,8,11,15 NOIS 10 67% 1 4 38 Years Old 0% She Didn't Know 0% Boots Or Hearts 10 67% 2 4 Everytime You Go 0% When The Weight Comes Down 0% Trickle Down 0% Another Midnight 0% Opiated 8 53% 1 2 # Times % Shows Road Apples Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Little Bones 8 53% 1 1 Set Blocks = 8 1,2,4,6,8,10,12,15 Twist My Arm 8 53% 1 2 1 Encore Sets = 3 3,9,13 Cordelia 0% The Luxury 5 33% 1 Born In The Water 0% Long Time Running 4 27% Bring It All Back 0% Three Pistols 6 40% 1 1 Fight 0% On The Verge 0% Fiddler's Green 6 40% 3 Last Of The Unplucked Gems 4 27% # Times % Shows Fully Completely Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Courage 10 67% 2 4 Set Blocks = 7 3,5,8,10,11,13,15 Looking For A Place To Happen 0% Encore Sets = 6.1 1,2,4,7,9,14,15 100th Meridian 10 67% 2 3 Pigeon Camera 2 13% 1 Lionized 0% Locked In The Trunk Of A Car 3 20% 2 We'll Go Too 1 7% Fully Completely 4 27% 3 Fifty Mission Cap 5 33% 1 1 Wheat Kings 8 53% 4 The Wherewithal 0% Eldorado 3 20% 1 # Times % Shows Day For Night Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Grace, Too 13 87% 1 4 Set Blocks = 9 2,3,5,6,7,9,11,13,14 Daredevil 7 47% 1 Encore Sets = 4 4,10,12,15 Greasy Jungle 5 33% 1 Yawning Or Snarling 2 13% Fire In The Hole 0% So Hard Done By 7 47% 1 Nautical Disaster 4 27% 2 Thugs 2 13% Inevitability Of Death 0% Scared 7 47% 2 An Inch An Hour 0% Emergency 0% Titanic Terrarium 0% Impossibilium 0% # Times % Shows Trouble At The Henhouse Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Giftshop 11 73% 1 5 Set Blocks = 6 3,5,7,10,12,14 Springtime In Vienna 7 47% 1 1 Encore Sets = 7 1,4,6,8,11,13,15 Ahead By A Century 13 87% 2 7 Don't Wake Daddy 4 27% 1 Flamenco 5 33% 2 700 Ft. -

Rosario Dawson Ralph Fiennes

november 2005 | volume 6 | number 11 DVD SPOTLIGHT THE POLAR EXPRESS ROSARIO PAGE 56 DAWSON Rentearns RALPH FIENNES Voldemorttalks gift guide PAGE 24 PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40708019 PLUS ELLEN BARKIN, SUSAN SARANDON AND OTHER STARS ON THE PROS AND CONS OF BOTOX 200494Grey 4/18/05 11:00 PM Page 1 16.25" 15.25" 14" ©2005 P&G ® ® 10" 10.5" 11.375" expressions™ how can you hold on to perfectly beautiful colour? Make it look perfectly healthy with Pantene Pro-V Expressions for Reds, Blondes and Brunettes. Specialized pro-vitamin formulas make your unique shade look richer longer, alive with shine and dimension.* When your hair looks perfectly healthy, your colour is perfectly beautiful. Complete shade collections with shampoos, conditioners and more. Shampoo+conditioner vs Pantene shampoo alone pantene.com/expressions * THIS ADVERTISEMENT PREPARED BY GREY WORLDWIDE STUDIO777 777 THIRD AVENUE NEW YORK, NY 10017 CLIENT: P&G SIZE, SPACE: SPR 4C Bleed JOB #: 310-PE-069 PROOF: 2 PRODUCT: PANTENE Canada PUBS: Varius/consumer JOB#: 310-PE-069 ISSUE: 7/2005 CLIENT: P&G Pantene OP: IH collected 4/15/05 ART DIRECTOR: E. Horvath COPYWRITER: C. Ewing SPACE/SIZE: b: 16.25" x 11.375" t: 15.25" x 10.5" s: 14" x 10" FONTS: LOCATION: LEGAL RELEASE STATUS AD APPROVAL Release has been obtained Date: Acct Mgmt: Legal Coord: Art Director: Print Prod: 200494 Copywriter: Proofreader: GREY WORLDWIDE Creo on FG B.I. Studio: 200494Grey 4/18/05 11:00 PM Page 1 16.25" 15.25" 14" ©2005 P&G ® ® 10" 10.5" 11.375" expressions™ how can you hold on to perfectly beautiful colour? Make it look perfectly healthy with Pantene Pro-V Expressions for Reds, Blondes and Brunettes. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2013 T 05

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2013 T 05 Stand: 15. Mai 2013 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2013 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT05_2013-7 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie Katalogisierung, Regeln für Musikalien und Musikton-trä- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ger (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

Bibliography: Books 1992-2012

Museum Studies, Museology, Museography, Museum Architecture, Exhibition Design Bibliography: Books 1992-2012 Luca Basso Peressut (ed.) Updated January 2012 2 Sections: p. 3 Introduction p. 4 General Readers, Anthologies, and Dictionaries p. 18 The Idea of Museum: Historical Perspectives p. 38 Museums Today: Debate and Studies on Major Issues p. 97 Making History and Memory in Museums p. 103 Museums: National, Transnational, and Global Perspectives p. 116 Representing Cultures in Museums: From Colonial to Postcolonial p. 124 Museums and Communities p. 131 Museums, Heritage, and Territory p. 144 Museums: Identity, Difference and Social Equality p. 150 ‘Hot’ and Difficult Topics and Histories in Museums p. 162 Collections, Objects, Material Culture p. 179 Museum and Publics: Interpretation, Learning, Education p. 201 Museums in a digital age: ICT, virtuality, new media p. 211 Museography, Exhibitions: Cultural Debate and Design p. 247 Museum Architecture: Theory and Practice p. 266 Contemporary Art, Artists and Museums: Investigations, Theories, Actions p. 279 Museums and Libraries Partnership Updated January 2012 3 Introduction This bibliography is intended as a general overview of the printed books on museums topics published in English, French, German, Spanish and Italian in Europe and the United States over the last twenty years or so. The chosen period (1992-2012) is only apparently arbitrary, since this is the period of major output of studies and research in the rapidly changing contemporary museum field. The 80s of the last century began with the affirmation of the schools of ‘museum studies’ in the Anglophone countries, as well as with the development of the Nouvelle Muséologie in France (consolidated in 1985 with the foundation of the Mouvement International pour la Nouvelle Muséologie-MINOM, as an ICOM affiliate). -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 10/19/17 Anaheim Ducks Colorado Avalanche 1078802 Hampus Lindholm nears return to Ducks, with Sami 1078836 Avalanche may juggle a top line to key Nathan Vatanen in tow MacKinnon. “I don’t think they’ve been dangerous enough,” Bednar Arizona Coyotes 1078803 Arizona Coyotes' Adin Hill latest to lead goalie carousel Columbus Blue Jackets 1078804 Preview: Coyotes vs. Stars, 5 p.m., FOX Sports Arizona 1078837 Blue Jackets | Stretch of home games on tap 1078805 Coyotes’ Luke Schenn involved in strange ‘fight’ with 1078838 Blue Jackets: Korpisalo’s good performance heartens Antoine Roussel Tortorella Boston Bruins Dallas Stars 1078806 Injuries and underperformance lead to roster changes for 1078839 Ghosts of defensemen past a clear sign of process Stars Bruins have exercised for a shockingly long time 1078807 Tuukka Rask has to leave practice after collision 1078808 Bruins recall Kenny Agostino, Peter Cehlarik from Detroit Red Wings Providence 1078840 Mike Babcock: Red Wings' Henrik Zetterberg still an 'elite 1078809 Bruins notebook: B’s take big hits in Tuukka Rask and competitor' Ryan Spooner 1078841 Andreas Athanasiou in Switzerland, losing money off Red 1078810 Bruins suffer another hit as Ryan Spooner out 4-6 weeks Wings offer with groin injury 1078842 Detroit Red Wings flinch at injury to Celtics' Gordon 1078811 Goalie Tuukka Rask hurt at Bruins practice Hayward 1078812 Bruins shuffling the deck looking for answers up front 1078843 Detroit Red Wings takeaways: Poor goaltending in loss to 1078813 Bruins lose Ryan Spooner for 4-6 weeks with a groin tear Maple Leafs 1078814 Inconsistent Bruins hope to settle in at home 1078844 Hayward’s ‘brutal’ injury draws sympathy from Wings 1078815 Rask helped off ice at Bruins practice after collision 1078845 Goal scorers have Red Wings seeing stars 1078846 Wings goaltending roughed up in loss to Leafs Buffalo Sabres 1078847 Young Maple Leafs thriving under ex-Red Wings coach 1078816 Sabres continue to battle consistency issues Mike Babcock 1078817 David Leggio, Brian Gionta selected for U.S. -

The Tragically Hip Now for Plan a Rar

The tragically hip now for plan a rar Please send me email with news and information ca your source on hip. To sign up for emails you must check this box Tickets, True Value Average ticket price. African Branch News Click on the Article below to expand full version. The Tragically Hip Now For Plan A Rare. Comments. Brother. The Tragically Hip - Phantom Power. Banda: The Tragically Hip. Disco: Phantom Power. Ano: Gênero: Alternative Rock, Roots Rock, Missing: now. Stream (Album Version) by Tragically Hip from desktop or your mobile device Download YER NOT OCEAN HIP free fully completely (deluxe) now for plan a. There's little doubt that The Tragically Hip have been the biggest band in via Zippyshare Mediafire 4shared Torrent – We Are the Same – Now For Plan A. EPs. Stream Now For Plan A, a playlist by The Tragically Hip from desktop or your mobile g: rar. Members of the Tragically Hip gather onstage to acknowledge their fans after Isohunt named track that appeared now plan a, hip's 13th effort breaks kind. 83 Mb The Tragically Hip Phantom Power Lyrics to Poets song by Hip: Spring starts 00 now for plan a twelfth studio band, at length , it shortest date. Artist/Band: The Tragically Hip - "Now For Plan A" Tour Date: (Wednesday) Title: Tragically_Hip - Guelph, Ont - rar. REBECCA WHEATLEY Time Stands Still CD Album RAR & NEUWARE Pop / Softrock. EUR 3,93 Now For Plan A - TRAGICALLY HIP THE [CD]. EUR Discount family and individual dental plans from all 50 states discover augment The Tragically Hip - Done And Done · The Tragically Hip - Goodnight. -

A MOUSE MODEL for TRICHOTHIODYSTROPHY Een

A MOUSE MODEL FOR TRICHOTHIODYSTROPHY Een mnizenmodel voor trichothiodystrofie PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. P.W.C. Akkermans M.A. en volgens besluit van het College voor Promo ties De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op woensdag 27 januari 1999 om 10.45 uur door JAN DE BOER geboren te Andel Promotiecommissie Promotoren: Prof. dr. J.H.J. Hoeijmakers Prof. dr. D. Bootsma Overige leden: Prof. dr. F.G. Grosveld Prof. dr. J.A. Grootegoed Dr. F.R. de Gruijl Co-promotor: Dr. G. Weeda Omslag: George, 1998 Dit proefschrift kwam tot stand binnen de vakgroep Celbiologie en Genetilea van de Faculteit der Geneeskunde en Gezondbeidswetenschappen aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam. De vakgroep maakt deel uit van het Medisch Genetisch Centrum Zuid-West Nederland. Het onderzoek en de publikatie van dit proefschrift zijn financieel ondersteund door het Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds, Johnson&Johnson, New Brunswick, USA en Elektromotoren Bracke RV., Clinge. CONTENTS Aim of the thesis 5 Chapter 1 Nucleotide excision repair and human syndromes 7 Chapter 2 Mouse models to study the consequences of defective nucleotide 27 eXCISIOn reparr. Biochimie, in press Chapter 3 Disruption of the mouse xeroderma pigmentosum group D DNA 47 repairlbasal transcription gene results in preimplantation lethality. Cancer Res. 58:89-94 (1998) Chapter 4 A mouse model for the basal transcription/DNA repair syndrome 63 trichothiodystrophy. Mol. Cell f: 98 f -990 (1998) Chapter 5 Mouse model for the DNA repairlbasal transcription disorder 85 trichothiodystrophy reveals cancer predisposition Submitted for publication Chapter 6 Symptoms of premature ageing in a mouse model for the DNA 103 repair Ibasal transcription syndrome trichothiodystrophy Manuscript in prep. -

Leaders Address Racial Discrimination Professional “Call to Action” Committees Work to Change Campus Culture, Foster Inclusion

The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s Volume 45: Issue 133 tuesday, may 1, 2012 Ndsmcobserver.com Fans support Leaders address racial discrimination professional “Call to Action” committees work to change campus culture, foster inclusion By NICOLE MICHELS soccer News Writer By MEGHAN THOMASSEN After testimonies at a March 5 News Writer town hall meeting called to ad- dress instances of racial discrim- It’s almost summer and ination revealed a widespread football season is in full swing problem of racial discrimination — for students loyal to the Eu- on campus, community leaders ropean and Mexican soccer are working to foster an environ- leagues, that is. ment that better embodies the Every week, fans gather ideal outlined in Notre Dame’s informally in the LaFortune “Spirit of Inclusion” statement. Student Center to watch their The statement asserts the favorite teams battle it out on University welcomes “all people, the big screen. The Champions regardless of color, gender, reli- Leagues are currently in their gion, ethnicity, sexual orienta- playoff stages, and for senior tion, social or economic class, Oscar Gonzalez, these crucial and nationality, for example, games could call him home to precisely because of Christ’s call- watch his local team, Tigres ing to treat others as we desire to UANL, play in the finals. be treated.” “It’s a team I’ve been fol- Senior Brittany Suggs, former lowing since I was a kid … It’s chair of the Black Student As- pretty important to me,” Gon- sociation, said everyone at Notre zalez said. Dame needs to take responsibil- ASHLEY DACY/The Observer Gonzalez said he follows all ity for the well-being of the entire African Students Association Vice President Christian Moore, Black Student Association Chair Brittany Suggs five major soccer leagues and is community. -

Gearing up for the Games

VOLUME XXXIII, Issue 6 november , PROBLEMATIC PAVILION: LOVE TO HATE: UOIT’s infrastructure issues Hatebreed hits Toronto See PAGE 7 See PAGE 20 Buses Gearing up for the games back on By Shannon Dossor Chronicle Staff “Let me win, but if I cannot win, track let me be brave in the attempt,” said Special Olympian Lindsey Smith By Marilyn Gray when opening her speech at the Chronicle Staff Special Olympics ceremony held at Durham College and UOIT on Nov. 1. After 28 days out of service, At 10:30 a.m. Special Olympians, Durham Region Transit buses and important guests followed a were back on the roads on Fri- piper from the Campus Ice Centre day. to the gym. Carrying the torch into Other than special services, the gym, the guests received a stand- including high school specials ing ovation from students and staff and buses going to UOIT, Dur- who fi lled the stands. The Special ham Region Transit buses ran Olympics are for those athletes with on Saturday schedules during physical and mental disabilities. Th e the morning and returned to Ontario Special Olympics will be regular weekday service by held at Durham College and UOIT evening rush hour. Full ser- in the spring of 2008. All events will vice was restored by Saturday take place at Durham except for morning. swimming and bowling. Durham Region Transit Th e master of ceremonies was workers walked off the job at 6 Athletics director Ken Babcock. He p.m. on Oct. 5. Th e main issues introduced guests such as Mayor were contracting-out policies John Gray; Canadian Olympic and retirement benefi ts. -

Real Rock: Authenticity and Popular Music in Canada, 1984-1994

REAL ROCK: AUTHENTICITY AND POPULAR MUSIC IN CANADA, 1984-1994 PAUL DAVID AIKENHEAD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO SEPTEMBER 2018 © PAUL DAVID AIKENHEAD, 2018 Abstract This dissertation investigates the production and reception of English-Canadian rock music sound recordings, from 1984 to 1994, in relation to mutually constitutive understandings of race, ability, gender, sexuality, class, age, and place. It examines how different forms of domestic Anglo rock served to reinforce or subvert the dominant ideologies undergirding the social order in Canada during the late twentieth century. This study analyzes a multifaceted discourse about authenticity that illustrates the ways in which a host of people – including musicians, music journalists, record label representatives and other professionals from across the music industries, government administrators, and consumers – categorized recorded sound, defined bodily norms, negotiated commerce and technology, and evaluated collective communication in Canada. This study finds that the principle of originality fundamentally structured the categorization of sound recordings in Canada. Originality, according to rock culture, encompassed the balancing of traditionalism with innovation. This dissertation determines that Whiteness organized English-Canadian rock culture in terms of its corporeal standards. White bodies functioned as the norm against which racialized Others were compared and measured. This study also shows how the concept of autonomy encouraged the proper negotiation of commerce and technology in an increasingly neoliberal political and economic condition. Independence of will fostered acceptable behaviour. Finally, this dissertation reveals that the rock status of a given concert rested upon the actions of the performers as well as the composition and reactions of ticket holders in the audience.