Penny Chapman Speech 290812

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIEW from the BRIDGE Marco Melbourne Theatre Company Dir: Iain Sinclair

sue barnett & associates DAMIAN WALSHE-HOWLING AWARDS 2011 A Night of Horror International Film Festival – Best Male Actor – THE REEF 2009 Silver Logie Nomination – Most Outstanding Actor – UNDERBELLY 2008 AFI Award Winner – Best Guest or Supporting Actor in a Television Drama – UNDERBELLY 2001 AFI Award Nomination – Best Actor in a Guest Role in a Television Series – THE SECRET LIFE OF US FILM 2021 SHAME John Kolt Shame Movie Pty Ltd Dir: Scott Major 2018 2067 Billy Mitchell Arcadia/Kojo Entertainment Dir: Seth Larney DESERT DASH (Short) Ivan Ralf Films Dir: Gracie Otto 2014 GOODNIGHT SWEETHEART (Short) Tyson Elephant Stamp Dir: Rebecca Peniston-Bird 2012 MYSTERY ROAD Wayne Mystery Road Films Pty Ltd Dir: Ivan Sen AROUND THE BLOCK Mr Brent Graham Around the Block Pty Ltd Dir; Sarah Spillane THE SUMMER SUIT (Short) Dad Renegade Films 2011 MONKEYS (Short) Blue Tongue Films Dir: Joel Edgerton POST APOCALYPTIC MAN (Short) Shade Dir: Nathan Phillips 2009 THE REEF Luke Prodigy Movies Pty Ltd Dir: Andrew Traucki THE CLEARING (Short) Adam Chaotic Pictures Dir: Seth Larney 2006 MACBETH (M) Ross Mushroom Pictures Dir: Geoffrey Wright 2003 JOSH JARMAN Actor Prod: Eva Orner Dir: Pip Mushin 2002 NED KELLY Glenrowan Policeman Our Sunshine P/L Dir: Gregor Jordan 2001 MINALA Dan Yirandi Productions Ltd Dir: Jean Pierre Mignon 1999 HE DIED WITH A FELAFEL IN HIS HAND Milo Notorious Films Dir: Richard Lowenstein 1998 A WRECK A TANGLE Benjamin Rectango Pty Ltd Dir: Scott Patterson TELEVISION 2021 JACK IRISH (Series 3) Daryl Riley ABC TV Dir: Greg McLean -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 01/12/2012 A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra ABB V.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.1 ABB V.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.2 ABB V.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.3 ABB V.4 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Schmidt ABO Above the rim ACC Accepted ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam‟s Rib ADA Adaptation ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes‟ smarter brother, The AEO Aeon Flux AFF Affair to remember, An AFR African Queen, The AFT After the sunset AFT After the wedding AGU Aguirre : the wrath of God AIR Air Force One AIR Air I breathe, The AIR Airplane! AIR Airport : Terminal Pack [Original, 1975, 1977 & 1979] ALA Alamar ALE Alexander‟s ragtime band ALI Ali ALI Alice Adams ALI Alice in Wonderland ALI Alien ALI Alien vs. Predator ALI Alien resurrection ALI3 Alien 3 ALI Alive ALL All about Eve ALL All about Steve ALL series 1 All creatures great and small : complete series 1 ALL series 2 All creatures great and small : complete series 2 ALL series 3 All creatures great and small : complete series 3 *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ALL series 4 All creatures great -

M Ed Ia R Elea Se

Talent USA: Australian creatives head stateside Tuesday 13 June 2017: Eleven directors, six screenwriters and ten online creators are being funded by Screen Australia to travel to the USA in June for a series of career growth opportunities. The screenwriters’ delegation is being co-sponsored by the Australian Writers Guild (AWG) and Scripted Ink. The directors and screenwriters will participate in Screen Australia’s Talent LA program taking part in a bespoke course of masterclasses, professional development activities and industry networking. The online creators will perform and host workshops at the world’s largest online video conference – Vidcon. “Given the burgeoning international demand for distinctive and engaging screen content, it is more important than ever for Screen Australia to promote and profile both our best creatives as well as production companies to the international sector,” said Richard Harris, Head of Business and Audience. “This Talent USA mission will showcase some of Australia’s most exciting emerging creative talent across feature film, TV and online to the American industry, while at the same time offering them a unique opportunity to access some of the most plugged-in creative and commercial minds in the business.” TALENT LA (June 26-29) Talent LA will be held at Charlie’s and the Creative Collective, the Australians in Film space at Raleigh Studios in West Hollywood. Leading US screen industry practitioners including Meg LeFauve, Sheila Hanahan MEDIA RELEASE Taylor, Joan Scheckel and Judith Weston will host a series of professional development and creative masterclasses. The emerging Australia directors selected are: • Sarah Bishop – known for comedy trio Skit Box, Sarah co-wrote/directed and starred in the sketch comedy series Wham Bam Thank You Ma’am and is currently in development on webseries Plus Ones for ABC iView and Public Relations for Revlover. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Sue Barnett & Associates

sue barnett & associates AARON JEFFERY TRAINING Graduate of the National Institute of Dramatic Art, 1993 FILM MOONROCK FOR MONDAY Bob Lunar Productions Dir: Kurt Martin THE FLOOD Mitch Harvest Pictures/Redman Entertainments Dir: Victoria Wharfe McIntyre PALM BEACH Doug Soapbox Industries Dir: Rachel Ward OCCUPATION Major Davis Sparke Films Dir: Luke Sparke RIP TIDE Owen The Steve Jaggi Company Dir: Rhiannon Bannenberg TURBO KID Frederic T&A Films Dir: Jason Eisner LOCKS OF LOVE: A FAMILIAR FEELING Terry Knox ScreenACT Dir: Adele Morey X-MEN ORIGINS: WOLVERINE Thomas Logan Wolverine Films Pty Ltd Dir: Gavin Hood BEAUTIFUL Alan Hobson Kojo Pictures Dir. Dean O’Flaherty STRANGE PLANET Joel Strange Planet Productions Dir: Emma Kate Croghan THE INTERVIEW Prior Interview Films P/L Dir: Craig Monaghan CARCRASH Narrator Binnaburra Film Corp. SQUARE ONE Jeremy Hostick Arcadia Pictures GOOD FRUIT Sharman Mezmo Pictures Dir: William Osack TELEVISION BETWEEN TWO WORLDS David Baines Seven Network Dir: Various UNDERBELLY FILES: CHOPPER Chopper Read Screentime Dir: Peter Andrikidis BLUE MURDER: KILLER COP (Mini-series) Chris Bronowski Endemol Shine Dir: Michael Jenkins JANET KING (Series 2) Simon Hamilton Screentime Dir: Peter Andrikidis/Grant Brown TEXAS RISING Ranger History Channel WENTWORTH (Series 3) Matt Fletcher FremantleMedia/Foxtel Dir: Kevin Carlin WENTWORTH (Series 2) Matt Fletcher FremantleMedia/Foxtel Dir: Kevin Carlin OLD SCHOOL Rick Matchbox Pictures Dir: Gregor Jordan WENTWORTH (Series 1) Matt Fletcher FremantleMedia/Foxtel Dir: Kevin -

Download the Press

Screen Australia and SBS present in association with Screen NSW, A Blackfella Films Production Media Kit as at 12.7.16 SBS Publicist Natalie Dubois T 02 9430 3824 M 0422 447 168 E [email protected] About the Production Two of Australia’s leading actors with international acclaim, Noah Taylor (Game of Thrones, Peaky Blinders) and Yael Stone (Orange is the New Black), star in SBS’s new Australian crime drama series, Deep Water. The four-hour crime thriller also stars William McInnes (The Time of Our Lives, The Slap), Danielle Cormack (Wentworth, Rake, Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries), Jeremy Lindsay Taylor (Gallipoli, Puberty Blues, Sea Patrol), Craig McLachlan (The Doctor Blake Mysteries), Dan Spielman (The Code, Accidental Soldier, Offspring), Ben Oxenbould (The Kettering Incident, Old School, Rake), Simon Burke (Devil’s Playground), John Brumpton (Catching Milat, Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries) and Victoria Haralabidou (The Code, East West 101, All Saints), Simon Elrahi (The Code), George H. Xanthis (The Principal) and Julian Maroun. From Blackfella Films, the producers of both the awarding-winning drama Redfern Now and factual program First Contact, Deep Water is SBS’s first cross-genre, cross-platform event which includes a four-part drama series, a feature documentary and unique online web series and content. The edge-of-your-seat drama was executive produced by SBS’s Sue Masters and produced by Blackfella Films’ Miranda Dear and Darren Dale (Redfern Now, Mabo, Ready For This) and written by Kris Wyld (East West 101) and Kym Goldsworthy (Love Child, Serangoon Road). SBS Director of Television and Online Content, Marshall Heald said: “SBS is proud that this important drama has attracted Australia’s finest creative professionals both in front – and behind the camera. -

Hiding Media Kit.Pdf

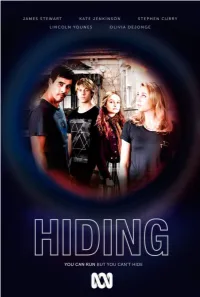

YOU CAN RUN BUT YOU CAN’T HIDE PREMIERES THURSDAY 5 FEBRUARY 8.30PM You can change your job, your city, your identity, but some things you can A bureaucratic bungle lands Mitchell (Lincoln Younes) and Tara (Olivia DeJonge) never escape. And they could cost Troy Quigg and his family their lives in the in a performing arts school. While it’s a happy outcome for aspirational uniquely gripping, family drama series, HIDING. fifteen year-old Tara, it’s torture for seventeen year-old surfer, Lincoln, who is desperate to get his old life back, especially his gorgeous girlfriend, Kelly After a botched drug deal, Troy (James Stewart) must take his family into (Jenna Kratzel). Adding to the teenager’s torment, no phones or Facebook, Witness Protection in exchange for giving evidence against his former no texts or twitter. Because a trace could bring a killer to their door. employer, vicious crime boss Nils Vandenberg (Marcus Graham). As the dysfunctional Swift family adjusts to their new world living with constant With new names and fresh identities, the Quigg family is ripped from their threat of corrupt cops or a leak within Witness Protection, a surprise phone home on the sun-drenched Gold Coast and dumped in a safe house in call unleashes an emotional upheaval that could crack their cover and bring Western Sydney as the Swift Family. But dislocation puts immense pressure those who want Lincoln silenced gunning for him and those he loves. on everyone. HIDING delivers a unique blend of humour and tension in this high stakes Lincoln Swift’s cover as a post-doctorate fellow in the Criminal Psychology family drama. -

© 2018 Mystery Road Media Pty Ltd, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Create NSW, Screenwest (Australia) Ltd, Screen Australia

© 2018 Mystery Road Media Pty Ltd, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Create NSW, Screenwest (Australia) Ltd, Screen Australia SUNDAYS AT 8.30PM FROM JUNE 3, OR BINGE FULL SEASON ON IVIEW Hotly anticipated six-part drama Mystery Road will debut on ABC & ABC iview on Sunday, 3 June at 830pm. Because just one episode will leave audiences wanting for more, the ABC is kicking off its premiere with a special back-to-back screening of both episodes one and two, with the entire series available to binge on iview following the broadcast. Contact: Safia van der Zwan, ABC Publicist, 0283333846 & [email protected] ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Filmed in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, Aaron Pedersen and Judy Davis star in Mystery Road – The Series a six part spin-off from Ivan Sen’s internationally acclaimed and award winning feature films Mystery Road and Goldstone. Joining Pedersen and Davis is a stellar ensemble casting including Deborah Mailman, Wayne Blair, Anthony Hayes, Ernie Dingo, John Waters, Madeleine Madden, Kris McQuade, Meyne Wyatt, Tasia Zalar and Ningali Lawford-Wolf. Directed by Rachel Perkins, produced by David Jowsey & Greer Simpkin, Mystery Road was script produced by Michaeley O’Brien, and written by Michaeley O’Brien, Steven McGregor, Kodie Bedford & Tim Lee, with Ivan Sen & the ABC’s Sally Riley as Executive Producers. Bunya Productions’ Greer Simpkin said: “It was a great honour to work with our exceptional cast and accomplished director Rachel Perkins on the Mystery Road series. Our hope is that the series will not only be an entertaining and compelling mystery, but will also say something about the Australian identity.” ABC TV Head of Scripted Sally Riley said: “The ABC is thrilled to have the immense talents of the extraordinary Judy Davis and Aaron Pedersen in this brand new series of the iconic Australian film Mystery Road. -

Law & Disorder

LAW & DISORDER RAKE LAW & DISORDER RAKE SERIES FOUR / 8 X ONE HOUR TV SERIES THURSDAY MAY 19 8.30PM STARRING RICHARD ROXBURGH WRITTEN BY PETER DUNCAN & ANDREW KNIGHT PRODUCED BY IAN COLLIE, PETER DUNCAN & RICHARD ROXBURGH ESSENTIAL MEDIA & BLOW BY BLOW MEDIA CONTACT Kristine Way / ABC TV Publicity T 02 8333 3844 M 0419 969 282 E [email protected] SERIES SYNOPSIS Last seen dangling from a balloon road leading straight to our dark drifting across the Sydney skyline, corridors of power. Cleaver Greene (Richard Roxburgh) Twisting and weaving the stories of crashes back to earth - literally and the ensemble of characters we’ve metaphorically, when he’s propelled grown to love over three stellar through a harbourside window into the seasons, Season 4 of Rake continues unwelcoming embrace of chaos past. the misadventures of dissolute Cleaver Fleeing certain revenge, Cleaver Greene and casts the fool’s gaze on all hightails it to a quiet country town, the levels of politics, the legal system, and reluctant member of a congregation our wider fears and obsessions. led by a stern, decent reverend and ALSO STARS Russell Dykstra, Danielle his flirtatious daughter. Before long Cormack, Matt Day, Adrienne Cleaver’s being chased back to Sin City. Pickering, Caroline Brazier, Kate Box, But Sydney has become a dark Keegan Joyce and Damien Garvey. place: terrorist threats and a loss of GUEST APPEARANCES from Miriam faith in authority have seen it take a Margolyes, Justine Clarke, Tasma turn towards the dystopian. When Walton, John Waters, Simon Burke, Cleaver finally emerges, he will be Rachael Blake, Rhys Muldoon, Louise accompanied by a Mistress of the Siversen and Sonia Todd. -

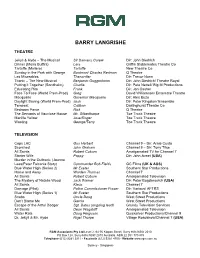

Barry Langrishe

BARRY LANGRISHE THEATRE Jekyll & Hyde – The Musical Sir Danvers Carew Dir: John Diedrich Dinner (Moira Buffini) Lars Griffin Stablemates Theatre Co Tartuffe (Moliere) Tartuffe New Theatre Co Sunday in the Park with George Boatman/ Charles Redman Q Theatre Les Miserables Thenardier Dir: Trevor Nunn Titanic – The New Musical Benjamin Guggenheim Dir: John Diedrich/ Theatre Royal Putting it Together (Sondheim) Charlie Dir: Pete Nettell/ Big M Productions Educating Rita Frank Dir: Jon Ossher Face To Face (World Prem-Prod) Greg David Williamson/ Ensemble Theatre Macquarie Governor Macquarie Dir: Alex Buzo Daylight Saving (World Prem-Prod) Josh Dir: Peter Kingston/ Ensemble Tempest Caliban Darlinghurst Theatre Co Bedroom Farce Nick Q Theatre The Servants of Vaucluse House Mr. Gilberthorpe Toe Truck Theatre Manilla Yellow Jose/Roger Toe Truck Theatre Wasting George/Terry Toe Truck Theatre TELEVISION Cops LAC Gus Herbert Channel 9 – Dir: Arnie Custo Scorched John Graham Channel 9 – Dir: Tony Tilse All Saints Robert Coburn Amalgamated TV for Channel 7 Starter Wife Pappy Dir: John Avnet (USA) Murder in the Outback: (Joanne Lees/Peter Falconia Story) Commander Bob Fields GC Films (UK & AUS) Blue Water High (Series 2) Mr Exeter Southern Star Productions Home and Away Warden Thomas Channel 7 All Saints Robert Coburn Amalgamated Television The Mystery of Natalie Wood Jack Warner Dir: Peter Bogdanovich (USA) All Saints Klaus Channel 7 Damage (Pilot) Police Commissioner Fraser Dir: Various/ AFTRS Blue Water High (Series 1) Mr Exeter Southern Star Productions Snobs Uncle Doug West Street Productions Don’t Blame Me Garcia West Street Productions Escape of the Artful Dodger Sgt. Bates (ongoing lead) Grundy Television Services All Saints Dean Wagstaff Amalgamated Television Water Rats Doug Ferguson Quicksilver Productions/Channel 9 Dr. -

Media-Kit-High-Ground.Pdf

HIGH GROUND DIRECTED BY STEPHEN JOHNSON RELEASE DATE TBC RUNNING TIME 1 HOUR 45 MINS RATED TBC MADMAN ENTERTAINMENT PUBLICITY CONTACT: Harriet Dixon-Smith - [email protected] Lydia Debus - [email protected] https://www.madmanfilms.com.au TAGLINE In a bid to save the last of his family, Gutjuk, a young Aboriginal man teams up with ex-soldier Travis to track down Baywara, the most dangerous warrior in the Territory, his Uncle. SYNOPSIS Northern Territory, Australia 1919. The Great War is over, the men have returned home. Many return to their normal lives in the cities in the south, others are drawn to the vast open spaces of the North. A sparsely populated wild frontier. They hunt buffalo, they hunt crocodile, and those that can join the overstretched Police service. Travis and Ambrose are two such men. A former sniper, Travis has seen the very worst of humanity and the only thing that keeps him on track is his code of honour, tested to its limit when a botched police operation results in the massacre of an Indigenous tribe. Travis saves a terrified young boy named Gutjuk from the massacre. He takes him to the safety of a Christian mission but unable to deal with the ensuing cover up, Travis leaves his police outpost and disappears into the bush. Twelve years later, 18-year-old Gutjuk hears news of the ‘wild mob’ – a renegade group of Indigenous warriors causing havoc along the frontier attacking and burning cattle stations, killing settlers. It’s said their leader is Gutjuk’s uncle, Baywara thought to be a survivor of the massacre. -

Online & on Demand 2017: Introduction

Online & On Demand 2017 Trends in Australian online viewing habits Online & On Demand 2017: Introduction Most Australians use the internet to watch professionally produced screen content. Online viewing is a new normal – one that supplements and challenges cinema and broadcast television, and that evolves as quickly as the technology that drives it. Screen Australia provides research on industry facts and trends to Contents inform government, industry and audiences. In 2014, Screen Australia released the ‘Online and on Demand’ report using Nielsen data, which Introduction 2 Key findings 3-4 showed how Australian audiences were using new online options. This Drivers, influencers and barriers 5-7 updated report examines major changes since 2014, including the Devices, locations and social media 8-11 Australian launch of subscription platforms such as Netflix and Stan, Viewing behaviours of VOD users 12-25 Overall platform use 12-16 the evolution of TV broadcaster online services, and the growth of Most-used services 17-23 YouTube, Facebook and other social services. Piracy 25 Attitudes of VOD users (to SVOD, companions) 26-27 Australian content behaviours 28-30 The findings are extensive. Australian video on demand users still Australian content attitudes 31-41 watch via traditional platforms, and they are watching more video – Dramas and documentaries 31 using broadcaster, subscription and advertising-driven options. They Paying for content 32 Children’s content 34 are pirating less. They choose what to watch based on old and new Favourite Australian titles 36-41 factors. And with the world’s content at their fingertips, Australian Appendix: Methodology, sample, terms 42-44 VOD users are seeking out Australian content, and want new Australian screen stories.