Arroyo Seco Watershed Restoration Feasibility Study Summary Report: Phase I Data Collection & Initial Planning Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topics in Modern Architecture in Southern California

TOPICS IN MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ARCH 404: 3 units, Spring 2019 Watt 212: Tuesdays 3 to 5:50 Instructor: Ken Breisch: [email protected] Office Hours: Watt 326, Tuesdays: 1:30-2:30; or to be arranged There are few regions in the world where it is more exciting to explore the scope of twentieth-century architecture than in Southern California. It is here that European and Asian influences combined with the local environment, culture, politics and vernacular traditions to create an entirely new vocabulary of regional architecture and urban form. Lecture topics range from the stylistic influences of the Arts and Crafts Movement and European Modernism to the impact on architecture and planning of the automobile, World War II, or the USC School of Architecture during the 1950s. REQUIRED READING: Thomas S., Hines, Architecture of the Sun: Los Angeles Modernism, 1900-1970, Rizzoli: New York, 2010. You can buy this on-line at a considerable discount. Readings in Blackboard and online. Weekly reading assignments are listed in the lecture schedule in this syllabus. These readings should be completed before the lecture under which they are listed. RECOMMENDED OPTIONAL READING: Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, 1971, reprint ed., Berkeley; University of California Press, 2001. Barbara Goldstein, ed., Arts and Architecture: The Entenza Years, with an essay by Esther McCoy, 1990, reprint ed., Santa Monica, Hennessey and Ingalls, 1998. Esther McCoy, Five California Architects, 1960, reprint ed., New York: -

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Robert and Climena O'brien House 3920 Adams Avenue - Normal Heights Neighborhood San Diego, California

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Robert and Climena O'Brien House 3920 Adams Avenue - Normal Heights Neighborhood San Diego, California Ronald V. May, RPA Kiley Wallace Legacy 106, Inc. P.O. Box 15967 San Diego, CA 92175 (619) 269-3924 www.legacy106.com March 2016 1 HISTORIC HOUSE RESEARCH Ronald V. May, RPA, President and Principal Investigator Kiley Wallace, Vice President and Architectural Historian P.O. Box 15967 • San Diego, CA 92175 Phone (619) 269-3924 • http://www.legacy106.com 2 3 State of California – The Resources Agency Primary # ___________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # ______________________________________ PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial __________________________________ NRHP Status Code 3S Other Listings ___________________________________________________________ Review Code _____ Reviewer ____________________________ Date __________ Page 3 of 24 *Resource Name or #: The Robert and Climena O'Brien House P1. Other Identifier: 3920 Adams Avenue, San Diego, CA 92116 *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County: San Diego and (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad: La Mesa Date: 1997 Maptech, Inc.T ; R ; ¼ of ¼ of Sec ; M.D. B.M. c. Address: 3920 Adams Avenue City: San Diego Zip: 92116 d. UTM: Zone: 11 ; mE/ mN (G.P.S.) e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc.) Elevation: 380 feet Legal Description: Villa Lot One Hundred Ninety-four (194) of Normal Heights according to map thereof No. 985, filed in the office of the County Recorder of said San Diego County May 9, 1906. *P3a. Description: (Describe resource and its major elements. Include design, materials, condition, alterations, size, setting, and boundaries). -

8 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 a B C D a B

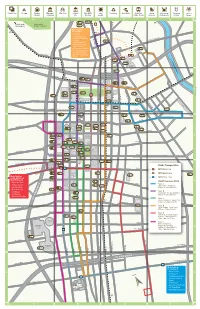

Public Plaza Art Spot Farmers Museum/ Bike Path Cultural Eco-LEED Solar Recycling Best Walks Light Rail Green Vegetarian Historical Special Market Institution Site Building Energy Public Transit Business Natural Cafe Feature Garden A B C D 7 3 Main St. Griffith Park/ Elysian Park/ Observatory Dodger Stadium 1 Metro Gold Line to Pasadena • Cornfield • Arroyo Seco Park • Debs Park-Audubon Broadway Society 8 Cesar Chavez Ave. 1 • Lummis House & 1 Drought Resistant Demo. Garden • Sycamore Grove Park 3 • S. Pasadena Library MTA • Art Center Campus Sunset Blvd. • Castle Green Central Park 3 Los Angeles River Union 6 Station 101 F R E E W AY 13 LADWP 1 Temple St. 12 12 10 9 8 Temple St. 2 2 San Pedro St. Broadway Main St. Spring St. 11 Los Angeles St. Grand Ave. Grand Hope St. 10 Figueroa St. Figueroa 1 11 9 3 3 Hill St. 1st St. 4 10 Alameda St. 1st St. Central Ave. Sci-Arc Olive St. Olive 7 1 2nd St. 2nd St. 6 5 8 6 2 3rd St. 4 3rd St. Flower St. Flower 4 3 2 W. 3rd St. 6 5 11 4 1 8 4th St. 4th St. 3 3 3 2 7 3 1 5 5th St. 1 5 12 5th St. 8 2 1 7 6 5 2 W. 6th St. 3 6th St. 3 7 6th St. 10 6 3 5 6 4 Wilshire Blvd. 9 14 Public Transportation 7th St. MTA Red Line 6 4 3 7 MTA Gold Line 7th St. 2 2 Metro Red Line to Mid-Wilshire & 5 MTA Blue Line North Hollywood 4 8th St. -

Pierpont Inn)

CITY OF VENTURA HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMITT££ Agenda Item: 2 Hearing mate: August 1, 2018 Project No: 10729 Case No: H RA-7-18-45998, H DPR-7-16-35882 Applicant: DKN Hotels Planner: Don Nielsen, Associate Planner, (805) ~~A~ Dave Ward, AICP, Planning Manager ~Y vv- Location: 550 Sanjon Road, 1471 and 1491 Visa del Mar (Attachment A) APNs: 076-0-021-160, 076-0-021-080 & 076-0-021-150 Recommendation: 1. Discuss the property owner's intended use of the building and how to approach exterior and interior modifications to the building; 2. Retain a qualified Landscape Historian to conduct a survey to establish or professionally estimate the ages of landscape features on the property, particularly for the larger landscape features (i.e. trees); 3. Encourage the applicant to revise the local Historic Landmark Designation application per criteria A, B, D, E and F; 4. Encourage the applicant to consider filing an application to list the Main Building on the California Register of Historic Places; and 5. Encourage the applicant to consider filing an application to list the Mattie Gleichmann House (50's Flat) on the National Register of Historic Places and the California Register of Historic Places. Zoning: Commercial Tourist Oriented (CTO) & Urban General 3 (T4.3) Land Use: Downtown Specific Plan (DTSP) Regulatory Review: SBMC Sec. 2.4.30.130 & 2R.450.220 Environmental Review: CEQA Guidelines Section 15306 - Information Collection PROJECT DESCRIPTION The proposed project is a Historic Resources Assessment for a combined 6.16 acre property containing nine buildings, including one designated Landmark, located at 550 PROJ-10729 HPC/08/01/18/DN Page1of19 DRC/HPC-1 Sanjon Road, and 1471 and 1491 Vista del Mar Drive in the Commercial Tourist Oriented (CTO) & Urban General 3 (T 4.3) zone districts with a land use designation of Downtown Specific Plan. -

Southern Californian 25

AT·H·E ~ HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF Southern Californian SOUTHERN The H i storical Society of Southern Califo r nia Volume 25 Number 3/4 CALIFORNIA OFFICERS Joh n 0. Poh lmann, Ph.D PRESIDENT Kenneth H. Marcus, Ph.D FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Linda Molino, Ph.D SECOND VICE PRESIDENT W illiam J. Barger, Ph.D SECRETARY I TREASURER Kevin Starr, Ph.D ADVISORY DIRECTOR Pat Adler-Ingram, Ph.D EX ECUTIVE DIRECTOR Greg Fischer Paul Bryan Gray Steve Hackel Andrew Krastins Charles Lumm is during construction of El Alisa!, Los Angeles, CA Braun Research Library Co llection, Autry National Center Cecilia Rasmussen Pau l Spitzzeri AnnWalnum HSSC Bids Farewell to the Lummis Home DIRECTOR~ The Historical Society of Southern California will HSSC's original lease expired and be leaving its headquarters in the Lummis Home within in 1989 the Los Angeles Department THE SOUTHERN the year. Our landlord, the Los Angeles Department of of Recreation and Parks issued a CALIFO RNIAN is published quarterly by Recreation and Parks, has decided that its needs would be new 10-year lease continuing the HSSC, a Ca li fornia better served by a different tenant; one that would focus on obligation to maintain the house and non-profit organization the Lummis Home as its sole activity and devote itself to open the site to the public. HSSC has (50 I )(c)(3) fundraising. Recreation and Parks has accordingly issued been requesting a renewal of our lease a "Request For Proposals," hoping to attract a suitable since the last expiration in 1999, in Pat Adler-Ingram, Ph.D concess1ona1re. -

Arroyo Seco Parkway National Scenic Byway Interpretive Plan

Arroyo Seco Parkway National Scenic Byway Interpretive Plan May 2012 This plan was prepared for Mountains Recreation Conservation Authority This plan was prepared by Engaging Places, LLC, a design and strategy (MRCA) in partnership with Caltrans with funding provided by a grant firm that connects people to historic places. from the National Scenic Byway program, funded in part by Federal Highway Administration Max A. van Balgooy Engaging Places, LLC Mountains Recreation & Conservation Authority 313 Twinbrook Parkway 570 West Avenue 26, Suite 100 Rockville, Maryland 20851-1567 Los Angeles, CA 90065 (301) 412-7940 [email protected] (323) 221-9944 EngagingPlaces.net 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 Section One: Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Calendar No. 598

Calendar No. 598 107TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 2d Session SENATE 107–279 SAN GABRIEL RIVER WATERSHEDS STUDY ACT SEPTEMBER 13, 2002.—Ordered to be printed Mr. BINGAMAN, from the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, submitted the following R E P O R T [To accompany S. 1865] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, to which was referred the bill (S. 1865) to authorize the Secretary of the Interior to study the suitability and feasibility of establishing the Lower Los Angles River and San Gabriel River watersheds in the State of California as a unit of the National Park System, and for other purposes, having considered the same, reports favorably thereon with an amendment and recommends that the bill, as amended, do pass. The amendment is as follows: Strike out all after the enacting clause and insert in lieu thereof the following: SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘San Gabriel River Watersheds Study Act of 2002’’. SEC. 2. AUTHORIZATION OF STUDY. (a) IN GENERAL.—The Secretary of the Interior (hereinafter in this Act referred to as the ‘‘Secretary’’, in consultation with the Secretary of Agriculture and the Sec- retary of the Army, shall conduct a comprehensive resource study of the following areas: (1) The San Gabriel River and its tributaries north of and including the city of Santa Fe Springs, and (2) The San Gabriel Mountains within the territory of the San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy (as defined in section 32603(c)(1)(C) of the State of California Public Resource Code). -

Charles F. Lummis Photographs of El Alisal, Family Members, and Other Subjects Photcl 72

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8xg9zcn No online items Charles F. Lummis photographs of El Alisal, family members, and other subjects photCL 72 Suzanne Oatey The Huntington Library 2020 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Charles F. Lummis photographs photCL 72 1 of El Alisal, family members, and other subjects photCL 72 Contributing Institution: The Huntington Library Photo Archives Title: Charles F. Lummis photographs of El Alisal, family members, and other subjects Identifier/Call Number: photCL 72 Physical Description: 9.1 Linear Feet (16 boxes) Date (inclusive): approximately 1888-1923 Abstract: A collection of photographs by American editor and writer Charles F. Lummis, featuring portraits of himself, family, and friends, and the building of his Los Angeles house, El Alisal. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for use by qualified researchers and by appointment. Please contact Reader Services at the Huntington Library for more information. RESTRICTED: Boxes 2-16: Due to fragility, glass plate negatives and autochromes available only with curatorial approval. Reference prints of the glass plate negatives are available (Box 1). There are no reference prints for the five autochromes. Conditions Governing Use The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. Charles F. Lummis photographs of El Alisal, family members, and other subjects, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. -

Highland Park Guidebook

ANGELS WALK® LA ANGELS WALK LA SPECIAL THANKS SUPPORTERS SELF-GUIDED HISTORIC TRAILS HONORARY CHAIRMAN LOS ANGELES MAYOR ERIC GARCETTI Bureau of Street Services, City of Los Angeles Nick Patsaouras CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES President, Polis Builders LTD Department of Transportation, City of Los Angeles COUNCILMEMBER GIL CEDILLO, CD1 BOARD HIGHLAND PARK HERITAGE TRUST Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Deanna Molloy, Founder & Board Chair HIGHLAND PARK-GARVANZA HPOZ Authority (Metro) Richard Kiwan, Retired LAUSD Teacher HISTORIC HIGHLAND PARK NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL Board of Directors Stanley Schneider, C.P.A. NORTH FIGUEROA ASSOCIATION Eric Garcetti, Mayor, City of Los Angeles STAFF VIRGINIA NEELY, HIGHLAND PARK HISTORICAL ARCHIVE Brian Lane, Co-Director Sheila Kuehl, Los Angeles County Supervisor Tracey Lane, Co-Director ADVISORS + FRIENDS Deanna Molloy, Director, Programs James Butts, City of Inglewood Mayor Kenny Hoff, Technology & Research Erin Behr Kathryn Barger, Los Angeles County Supervisor Spencer Green, Research & Administration Robin Blair, Senior Director of Operations Support, Metro Mike Bonin, Council Member CD11 CONTRIBUTORS Ferdy Chan, Bureau of Street Services Adilia Clerk, Bureau of Street Services John E. Molloy, Urban Planner & Consultant Jacquelyn Dupont-Walker Charles J. Fisher, Historian & Contributing Writer Carol Colin, Highland Park Ebell Club John Fasana, Mayor Pro Tem, City of Duarte Eric Brightwell, Researcher & Contributing Writer Greg Fischer Kathy Gallegos, Avenue 50 Studio Walter -

The Southern Californian Newsletter NAME ------$ 1,000 Benefactor All of the Above Plus

AT·H·E~ HISTORICAL The Southern SOCIETY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Californian The Historical Society of Southern California Summer 20 I 2 Volume 24 Number 2 OFFICERS Spring Arrives at the Lummis Home John 0. Pohlmann, Ph.D PRESIDENT Kenneth H. Marcus, Ph.D F1RSTVICE PRESIDENT Linda Molino, Ph.D SECOND VICE PRESIDENT Eric A Nelson, Esq. SECRETARY William J. Barger, Ph.D TREASURER DIRECTORS Greg Fischer Steve Hackel Lourdes Nunez-Burgess Cecilia Rasmussen Paul Spitzzeri AnnWalnum ADVISORY DIRECTOR Kevin Starr Pat Adler-Ingram, Ph.D Pink evening primroses thriving in the water wise garden ExECLJTIVE DIRECTOR This spring the dancing pink flowers of "The flower-temper of my own land has shifted visibly ESOUTHERN CALIFORNIAN the Mexican evening primrose (Oenothera speciosa in the ten years since I began to live on what I have is published quarterly by the childsii) are opening farther into the yarrow meadow tried seriously to keep wild. A very beautiful tiny white Historical Society of Southern California, and closer to the path than before. "Wildness" in the daisy, of which there were once millions, has become a California non-profit Lummis garden means that the flowers respond to almost extinct." [The Carpet of God's Country, Out organization (SO I)(c)(3) variations in winter rains by shifting their time of West Magazine, Vol. 22, May 1905, 306-317.] Next Romualdo Valenzuela blooming and, in the case of these lovely blossoms, it time you visit the Lummis House look for the returning NEVVSL.ElTER LAYOUT may be a response to a loss of sunshine because of the daisies on the warm, dry slope to the right as you enter widening shadow cast by the big oak tree. -

Chicken Boy Gazette Chickenboy.Com

chickenboy.com chickenboyshop.com Chicken Boy Gazette futurestudiogallery.com Chicken Boy © & TM Future Studio MAY 2018 • THE STATUE OF LIBERTY OF LOS ANGELES IN HIGHLAND PARK SINCE 2007 chicken boy at future studio • 5558 North figueroa Street • los angeles 90042 North Figueroa Streetscape Mosaics SOUTH AVENUE 59 TILE: Two trollies along North Figueroa Street and Avenue Along both sides of Figueroa, between Avenue10/22/13 50 and Avenue 60, you’ll 57 in 1906, looking north. In 1895, the 10/22/13 HIGHLAND PARK STREETSCAPEfind IMPROVEMENT intricately designed PROJECT mosaics embedded into the sidewalk beneath your HIGHLAND PARK STREETSCAPE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT TILE MOSAICS Pasadena Street Railroad Electric Line feet and recently installed by Axiom Group. Designed by SWA Landscape mergedTILE MOSAICS with the Los Angeles Electric 50-60 Architects, who conceived the idea of bringing historical mosaics to the Railway50-60 to form the Pasadena and Los Figueroa Corridor, and created by Brailsford Public Art, these colorful Angeles Railway. This line ran from mosaics celebrate key scenes from the history of Highland Park. This project downtown through Highland Park and Garvanza to Pasadena and back. That falls within one of fifteen areas being revitalized under Mayor Garcetti’s same year, Highland Park was annexed to Great Streets Program, and was the result of close collaboration between the the City of Los Angeles and established community and city, including the Office of Councilmember Gil Cedillo and one of the city’s first suburbs. Los Angeles Neighborhood Initiative (LANI) and was made possible by a Courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library federally funded program that allows states and localities to preserve and improve pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure. -

Regular Meeting Agenda Board of Recreation And

REGULAR MEETING AGENDA BOARD OF RECREATION AND PARK COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES Wednesday, April 5, 2017 at 9:00 a.m. TOUR OF THE SOUTH LOS ANGELES WETLANDS PARK 5413 Avalon Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90011 Wednesday, April 5, 2017 at 9:30 a.m. South Park Recreation Center Gymnasium 345 East 51st Street Los Angeles, CA 90011 SYLVIA PATSAOURAS, PRESIDENT LYNN ALVAREZ, VICE PRESIDENT MELBA CULPEPPER, COMMISSIONER PILAR DIAZ, COMMISSIONER MISTY M. SANFORD, COMMISSIONER EVERY PERSON WISHING TO ADDRESS THE COMMISSION MUST COMPLETE A SPEAKER’S REQUEST FORM AT THE MEETING AND SUBMIT IT TO THE COMMISSION EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT PRIOR TO THE BOARD’S CONSIDERATION OF THE ITEM. PURSUANT TO COMMISSION POLICY, COMMENTS BY THE PUBLIC ON AGENDA ITEMS WILL BE HEARD ONLY AT THE TIME THE RESPECTIVE ITEM IS CONSIDERED, FOR A CUMULATIVE TOTAL OF UP TO FIFTEEN (15) MINUTES FOR EACH ITEM. ALL REQUESTS TO ADDRESS THE BOARD ON PUBLIC HEARING ITEMS MUST BE SUBMITTED PRIOR TO THE BOARD’S CONSIDERATION OF THE ITEM. COMMENTS BY THE PUBLIC ON ALL OTHER MATTERS WITHIN THE SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION OF THE BOARD WILL BE HEARD DURING THE “GENERAL PUBLIC COMMENT” PERIOD OF THE MEETING. EACH SPEAKER WILL BE GRANTED TWO MINUTES, WITH FIFTEEN (15) MINUTES TOTAL ALLOWED FOR PUBLIC PRESENTATION. 1. CALL TO ORDER AND TOUR OF SOUTH LOS ANGELES WETLANDS PARK A Tour of the South Los Angeles Wetlands Park will begin at the parking lot located within the wrought iron gates at 5413 Avalon Boulevard at 54th Street, Los Angeles, CA 90011. After the Tour, the following Agenda items are to be considered at South Park Recreation Center 2.