Serum Androgen Profiles in Women with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex Hormones Related Ocular Dryness in Breast Cancer Women

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Sex Hormones Related Ocular Dryness in Breast Cancer Women Antonella Grasso 1, Antonio Di Zazzo 2,* , Giuseppe Giannaccare 3 , Jaemyoung Sung 4 , Takenori Inomata 4 , Kendrick Co Shih 5 , Alessandra Micera 6, Daniele Gaudenzi 2, Sara Spelta 2 , Maria Angela Romeo 7, Paolo Orsaria 1, Marco Coassin 2 and Vittorio Altomare 1 1 Breast Unit, University Campus Bio-Medico, 00128 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (P.O.); [email protected] (V.A.) 2 Ophthalmology Operative Complex Unit, University Campus Bio-Medico, 00128 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (D.G.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.C.) 3 Department of Ophthalmology, University Magna Graecia of Catanzaro, 88100 Catanzaro, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, Juntendo University, 1130033 Tokyo, Japan; [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (T.I.) 5 Department of Ophthalmology, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; [email protected] 6 Research and Development Laboratory for Biochemical, Molecular and Cellular Applications in Ophthalmological Sciences, IRCCS–Fondazione Bietti, 00198 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 7 School of Medicine, Humanitas University, 20089 Milan, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-06225418893; Fax: +39-9622541456 Abstract: Background: Dry eye syndrome (DES) is strictly connected to systemic and topical sex hor- mones. Breast cancer treatment, the subsequent hormonal therapy, the subsequent hyperandrogenism and the early sudden menopause, may be responsible for ocular surface system failure and its clinical Citation: Grasso, A.; Di Zazzo, A.; manifestation as dry eye disease. -

Androgens Utilization Management Criteria

ANDROGENS UTILIZATION MANAGEMENT CRITERIA DRUG CLASS: Androgens Generic (Brand) NAMES: • Fluoxymesterone (Androxy®) • Methyltestosterone (Android®, Methitest®, Testred®) • Testosterone, topical A. Androderm®, Androgel® - Preferred topical testosterone ® ® ® ™ B. Testim , Fortesta , Axiron , Bio-T-Gel • Testosterone, buccal (Striant®) • Testosterone cypionate (e.g., Depo-Testosterone®) • Testosterone enanthate (e.g., Delatestryl®) FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS: Replacement therapy in conditions associated with a deficiency or absence of endogenous testosterone. Primary hypogonadism (congenital or acquired): Testicular failure due to cryptorchidism, bilateral torsion, orchitis, vanishing testis syndrome, orchidectomy, Klinefelter syndrome, chemotherapy, or toxic damage from alcohol or heavy metals. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (congenital or acquired): Idiopathic gonadotropin or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) deficiency or pituitary-hypothalamic injury from tumors, trauma, or radiation. Delayed puberty: To stimulate puberty in carefully selected males with clearly delayed puberty. Metastatic mammary cancer in women: Used secondarily in women with advancing inoperable metastatic (skeletal) mammary cancer who are 1 to 5 years postmenopausal COVERAGE AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA for the androgen products listed above: 1. Being used for ONE of the following: a. Males for the treatment of hypogonadism (low testosterone): i. patient has symptoms of androgen deficiency AND ii. has a baseline (pre-treatment) morning serum total testosterone level of less than or equal to 300 ng/dL or a serum total testosterone level that is below the testing laboratory’s lower limit of the normal range OR iii. baseline morning serum free testosterone level, measured by the equilibrium dialysis method, of less than or equal to 50 pg/ml or a free serum testosterone level that is below the testing laboratory’s lower limit of the normal range, OR b. -

Health Risks Associated with Long-Term Finasteride and Dutasteride Use: It’S Time to Sound the Alarm

Review Article Health promotion, disease prevention, and lifestyle pISSN: 2287-4208 / eISSN: 2287-4690 World J Mens Health 2020 Jul 38(3): 323-337 https://doi.org/10.5534/wjmh.200012 Health Risks Associated with Long-Term Finasteride and Dutasteride Use: It’s Time to Sound the Alarm Abdulmaged M. Traish Department of Urology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA 5α-dihydrotestosterone (5α-DHT) is the most potent natural androgen. 5α-DHT elicits a multitude of physiological actions, in a host of tissues, including prostate, seminal vesicles, hair follicles, skin, kidney, and lacrimal and meibomian glands. How- ever, the physiological role of 5α-DHT in human physiology, remains questionable and, at best, poorly appreciated. Recent emerging literature supports a role for 5α-DHT in the physiological function of liver, pancreatic β-cell function and survival, ocular function and prevention of dry eye disease and kidney physiological function. Thus, inhibition of 5α-reductases with finasteride or dutasteride to reduce 5α-DHT biosynthesis in the course of treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or male pattern hair loss, known as androgenetic alopecia (AGA) my induces a novel form of tissue specific androgen deficien- cy and contributes to a host of pathophysiological conditions, that are yet to be fully recognized. Here, we advance the con- cept that blockade of 5α-reductases by finasteride or dutasteride in a mechanism-based, irreversible, inhabitation of 5α-DHT biosynthesis results in a novel state of androgen deficiency, independent of circulating testosterone levels. Finasteride and dutasteride are frequently prescribed for long-term treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men with BPH and in men with AGA. -

Androgen Deficiency Guideline Results

Improving testosterone testing in people living with HIV V. Kopanitsa1, S. Flavell2, J. Ashby2, I. Ghosh2, S. Candfield2, U. Srirangalingm2, L. Waters2 1. University College London (UCL) Medical School; 2. Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust Introduction Aims Symptomatic testosterone (T) deficiency is more common in people living 1. Review local practice in the clinic with HIV (PLWH) than the HIV negative male population; despite this, 2. Introduce a local guideline with investigation and management pathways specific guidelines are lacking. [1,2] for assessing T deficiency in PLWH with a view to earlier diagnosis and more efficient use of resources Patients with T deficiency can experience a number of symptoms such as 3. Re-audit after guideline implementation erectile dysfunction (ED) and reduced libido, and also less specific symptoms including low mood, fatigue and reduced muscle mass [1,2,3]. Total T (free and protein-bound) is the most common measurement reported Methods when a testosterone test is requested. In PLWH, raised sex hormone 1. A retrospective notes review was completed on all patients who had a T binding globulin (SHBG) levels are common, and so calculation of free T test between 01/06/17 and 30/11/17, and 17/09/18 to 14/12/18, before more accurately reflects T levels in this group. SHBG and Albumin tests are and after guideline implementation, respectively. The following outcomes needed for this for this calculation, which is done via an online calculator [4]. from the guideline were assessed: T also varies by circadian rhythm and should be measured at peak time in 2. -

Androgen Deficiency Diagnosis and Management

4 Clinical Summary Guide Androgen Deficiency Diagnosis and management Androgen deficiency (AD) * Pituitary disease, thalassaemia, haemochromatosis. • Androgen deficiency is common, affecting 1 in 200 men under ** AD is an uncommon cause of ED. However, all men presenting 60 years with ED should be assessed for AD • The clinical presentation may be subtle and its diagnosis Examination and assessment of clinical features of AD overlooked unless actively considered Pre-pubertal onset – Infancy The GP’s role • Micropenis • GPs are typically the first point of contact for men with • Small testes symptoms of AD • The GP’s role in the management of AD includes clinical Peri-pubertal onset – Adolescence assessment, laboratory investigations, treatment, referral • Late/incomplete sexual and somatic maturation and follow-up • Small testes • Note that it in 2015 the PBS criteria for testosterone • Failure of enlargement of penis and skin of scrotum becoming prescribing changed; the patient must be referred for a thickened/pigmented consultation with an endocrinologist, urologist or member of • Failure of growth of the larynx the Australasian Chapter of Sexual Health Medicine to be eligible for PBS-subsidised testosterone prescriptions • Poor facial, body and pubic hair • Gynecomastia Androgen deficiency and the ageing male • Poor muscle development • Ageing may be associated with a 1% decline per year in serum Post-pubertal onset – Adult total testosterone starting in the late 30s • Regression of some features of virilisation • However, men who -

Male Hypogonadism: Quick Reference for Residents

Male hypogonadism: Quick Reference for Residents Soe Naing, MD, MRCP(UK), FACE Endocrinologist Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine Director of Division of Endocrinology Medical Director of Community Diabetes Care Center UCSF-Fresno Medical Education Program Version: SN/8-21-2017 Male hypogonadism From Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e and Up-To-Date accessed on 8-21-2017 Testosterone is FDA-approved as replacement therapy only for men who have low testosterone levels due to disorders of the testicles, pituitary gland, or brain that cause hypogonadism. Examples of these disorders include primary hypogonadism because of genetic problems, or damage from chemotherapy or infection (mump orchitis). However, FDA has become aware that testosterone is being used extensively in attempts to relieve symptoms in men who have low testosterone for no apparent reason other than aging. Some studies reported an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, or death associated with testosterone treatment, while others did not. FDA cautions that prescription testosterone products are approved only for men who have low testosterone levels caused by a medical condition. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm436259.htm 2 Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis Schematic representation of the hypothalamic-pituitary- testicular axis. GnRH from the hypothalamus stimulates the gonadotroph cells of the pituitary to secrete LH and FSH. LH stimulates the Leydig cells of the testes to secrete testosterone. The high concentration of testosterone within the testes is essential for spermatogenesis within the seminiferous tubules. FSH stimulates the Sertoli cells within the seminiferous tubules to make inhibin B, which also stimulates spermatogenesis. Testosterone inhibits GnRH secretion, and inhibin B inhibits FSH secretion. -

Management of Women with Premature Ovarian Insufficiency

Management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency Guideline of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology POI Guideline Development Group December 2015 1 Disclaimer The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (hereinafter referred to as 'ESHRE') developed the current clinical practice guideline, to provide clinical recommendations to improve the quality of healthcare delivery within the European field of human reproduction and embryology. This guideline represents the views of ESHRE, which were achieved after careful consideration of the scientific evidence available at the time of preparation. In the absence of scientific evidence on certain aspects, a consensus between the relevant ESHRE stakeholders has been obtained. The aim of clinical practice guidelines is to aid healthcare professionals in everyday clinical decisions about appropriate and effective care of their patients. However, adherence to these clinical practice guidelines does not guarantee a successful or specific outcome, nor does it establish a standard of care. Clinical practice guidelines do not override the healthcare professional's clinical judgment in diagnosis and treatment of particular patients. Ultimately, healthcare professionals must make their own clinical decisions on a case-by-case basis, using their clinical judgment, knowledge, and expertise, and taking into account the condition, circumstances, and wishes of the individual patient, in consultation with that patient and/or the guardian or carer. ESHRE makes no warranty, express or implied, regarding the clinical practice guidelines and specifically excludes any warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular use or purpose. ESHRE shall not be liable for direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages related to the use of the information contained herein. -

TUE Physician Guidelines 1. Medical Condition Hypogonadism in Men Is

TUE Physician Guidelines MALE HYPOGONADISM 1. Medical Condition Hypogonadism in men is a clinical syndrome that results from failure of the testes to produce physiological levels of testosterone (testosterone deficiency) and in some instances normal number of spermatozoa (infertility) due to disruption of one or more levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis. The two distinct yet interdependent testicular functions, steroidogenesis (testosterone production) and spermatogenesis can fail independently. Testosterone deficiency is the focus of this document. 2. Diagnosis A. Etiology Hypogonadism may be primary, due to a problem with the testes, or secondary, due to a problem with the hypothalamus or pituitary gland or combined primary and secondary. The etiology of testosterone deficiency may be organic, in which there is a pathological structural or congenital defect within the hypothalamic-pituitary- testicular axis. Hypogonadism may be functional in which there is no observable pathological change in the structures within the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis. Hypogonadism may be functional in which there is no observable pathological change in the structures within the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis. Organic hypogonadism is usually long-lasting or permanent while functional hypogonadism is potentially reversible. TUE should only be approved for hypogonadism that has an organic etiology. TUE should not be approved for androgen deficiency due to functional disorder. TUE for androgen deficiency should not be approved for females. Organic causes of hypogonadism (See Appendix A for a more detailed list) 1. Organic primary hypogonadism may be due to: a. Genetic abnormalities b. Developmental abnormalities c. Testicular trauma, bilateral orchiectomy, testicular torsion d. Orchitis e. Radiation treatment or chemotherapy. -

Hyperandrogenic States in Women: Pitfalls in Laboratory Diagnosis

4 178 M Pugeat and others Laboratory diagnosis of 178:4 R141–R154 Review hyperandrogenic states MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE Hyperandrogenic states in women: pitfalls in laboratory diagnosis Michel Pugeat1,2,3, Ingrid Plotton2,4, Aude Brac de la Perrière1, Gérald Raverot1,2, Henri Déchaud1,2 and Véronique Raverot4 1Fédération d’Endocrinologie, Groupement Hospitalier Est, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Bron, France, 2Université Claude Correspondence Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France, 3INSERM U1060 Institut CarMen, Lyon, France, and 4Laboratoire d’Hormonologie, should be addressed d’Endocrinologie Moléculaire et des Maladies Rares, Groupement Hospitalier Est, Hospices Civils de Lyon, to M Pugeat Bron, France Email [email protected] Abstract Measuring total testosterone level is the first-line approach in assessing androgen excess in women. The main pitfalls in measuring testosterone relate to its low concentration and to the structural similarity between circulating androgens and testosterone, requiring accurate techniques with high specificity and sensitivity. These goals can be achieved by immunoassay using a specific anti-testosterone monoclonal antibody, ideally after an extraction step. Liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) will be commonly used for measuring testosterone, providing optimal accuracy with a low limit of detection. Yet, the pitfalls of these two techniques are well identified and must be recognized and systematically addressed. In general, laboratories using direct testosterone immunoassay and mass spectrometry need to operate within a quality framework and be actively engaged in external quality control processes and standardization, so as to ensure appropriate interpretation irrespective of the particular laboratory. Circulating testosterone is strongly bound to sex-hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), and SHBG levels are typically low in overweight hyperandrogenic patients. -

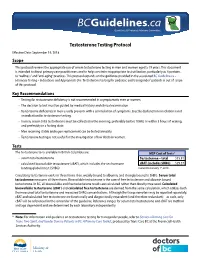

2. Testosterone Testing

Guidelines & Protocols Advisory Committee Testosterone Testing Protocol Effective Date: September 19, 2018 Scope This protocol reviews the appropriate use of serum testosterone testing in men and women aged ≥ 19 years. This document is intended to direct primary care practitioners and to help constrain inappropriate test utilization, particularly as it pertains to “wellness” and “anti-aging” practices. This protocol expands on the guidance provided in the associated BC Guideline.ca – Hormone Testing – Indications and Appropriate Use. Testosterone testing for pediatric and transgender* patients is out of scope of this protocol. Key Recommendations • Testing for testosterone deficiency is not recommended in asymptomatic men or women. • The decision to test must be guided by medical history and clinical examination. • Testosterone deficiency in men usually presents with a constellation of symptoms. Erectile dysfunction in isolation is not an indication for testosterone testing. • In men, serum total testosterone must be collected in the morning, preferably before 10AM, or within 3 hours of waking, and preferably in a fasting state. • Men receiving stable androgen replacement can be tested annually. • Testosterone testing is not useful for the investigation of low libido in women. Tests The testosterone tests available in British Columbia are: MSP Cost of Tests1 • serum total testosterone Testosterone – total $15.81 • calculated bioavailable testosterone (cBAT), which includes the sex hormone cBAT (includes SHBG) $29.37 binding globulin test (SHBG) Current to January 1st, 2018 Circulating testosterone exists in three forms: free, weakly bound to albumin, and strongly bound to SHBG. Serum total testosterone measures all three forms. Bioavailable testosterone is the sum of free testosterone and albumin bound testosterone. -

Evolution of Guidelines for Testosterone Replacement Therapy

Journal of Clinical Medicine Editorial Evolution of Guidelines for Testosterone Replacement Therapy Hyun Jun Park 1 , Sun Tae Ahn 2 and Du Geon Moon 2,* 1 Department of Urology and Medical Research Institute of Pusan National University Hospital, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Busan 49241, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Urology, Korea University Guro Hospita, l No. 148, Gurodong-ro, Guro-gu, Seoul 08308, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-2626-3201 Received: 16 March 2019; Accepted: 20 March 2019; Published: 25 March 2019 Abstract: Testosterone is an essential hormone required for the developmental growth and maintenance of the male phenotype during the whole life. With the increasing male life expectancy worldwide and development of adequate testosterone preparations, the prescription of testosterone has increased tremendously. Testosterone replacement should be based on low serum testosterone and related clinical symptoms. In the last two decades, with the accumulation of data, official recommendations have evolved in terms of definition, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. In practice, it is better for physicians to follow the Institutional Official Recommendations or Clinical Practice Guideline for an adequate diagnosis and treatment of testosterone deficiency. Currently, four official recommendations are available for diagnosis and treatment of patients with testosterone deficiency. The inconsistencies in the guidelines merely create confusion among the physicians instead of providing clear information. Furthermore, there is no definite method to assess serum testosterone and clinical symptoms. In the era of active testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), physicians’ practice patterns should be consistent with the clinical practice guidelines to avoid the misuse of testosterone. -

EAU Guidelines on Male Hypogonadism 2016

EAU Guidelines on Male Hypogonadism G.R. Dohle (Chair), S. Arver, C. Bettocchi, T.H. Jones, S. Kliesch, M. Punab © European Association of Urology 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Aim 4 1.2 Publication history 4 1.3 Panel composition 4 2. METHODS 4 2.1 Review 4 3. EPIDEMIOLOGY, AETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY 5 3.1 Epidemiology 5 3.1.1 Role of testosterone for male reproductive health 5 3.2 Physiology 5 3.2.1 The androgen receptor 5 3.3 Aetiology 6 3.4 Classification 7 3.4.1 Male hypogonadism of testicular origin (primary hypogonadism) 7 3.4.2 Male hypogonadism of hypothalamic-hypopituitary origin (secondary hypogonadism) 7 3.4.3 Male hypogonadism due to mixed dysfunction of hypothalamus/pituitary and gonads 7 3.4.4 Male hypogonadism due to defects of androgen target organs 7 4. DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION 9 4.1 Clinical symptoms 9 4.2 History-taking and questionnaires 10 4.3 Physical examination 11 4.4 Summary of evidence and recommendations for the diagnostic evaluation 11 4.5 Clinical consequences of hypogonadism 11 4.5.1 Prenatal androgen deficiency 11 4.5.2 Prepubertal onset of androgen deficiency 11 4.5.3 Adult-onset hypogonadism 12 4.5.3.1 Recommendations for screening men with adult-onset hypogonadism 12 5. DISEASE MANAGEMENT 13 5.1 Indications and contraindications for treatment 13 5.2 Benefits of treatment 13 5.3 Choice of treatment 14 5.3.1 Preparations 14 5.3.1.1 Testosterone undecanoate 14 5.3.1.2 Testosterone cypionate and enanthate 14 5.3.1.3 Transdermal testosterone 14 5.3.1.4 Sublingual and buccal testosterone 14 5.3.1.5 Subdermal depots 15 5.4 Hypogonadism and fertility issues 15 5.5 Recommendations for testosterone replacement therapy 16 5.6 Risk factors in testosterone treatment 16 5.6.1 Male breast cancer 16 5.6.2 Risk for prostate cancer 16 5.6.3 Cardiovascular diseases 16 5.6.4 Obstructive sleep apnoea 18 5.7 Summary of evidence and recommendations on risk factors in testosterone treatment 18 6.