Undermining Workers' Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

The Philippines Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile THE PHILIPPINES HOTSPOT final version December 11, 2001 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 The Ecosystem Profile 3 The Corridor Approach to Conservation 3 BACKGROUND 4 BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF THE PHILIPPINES HOTSPOT 5 Prioritization of Corridors Within the Hotspot 6 SYNOPSIS OF THREATS 11 Extractive Industries 11 Increased Population Density and Urban Sprawl 11 Conflicting Policies 12 Threats in Sierra Madre Corridor 12 Threats in Palawan Corridor 15 Threats in Eastern Mindanao Corridor 16 SYNOPSIS OF CURRENT INVESTMENTS 18 Multilateral Donors 18 Bilateral Donors 21 Major Nongovernmental Organizations 24 Government and Other Local Research Institutions 26 CEPF NICHE FOR INVESTMENT IN THE REGION 27 CEPF INVESTMENT STRATEGY AND PROGRAM FOCUS 28 Improve linkage between conservation investments to multiply and scale up benefits on a corridor scale in Sierra Madre, Eastern Mindanao and Palawan 29 Build civil society’s awareness of the myriad benefits of conserving corridors of biodiversity 30 Build capacity of civil society to advocate for better corridor and protected area management and against development harmful to conservation 30 Establish an emergency response mechanism to help save Critically Endangered species 31 SUSTAINABILITY 31 CONCLUSION 31 LIST OF ACRONYMS 32 2 INTRODUCTION The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is designed to better safeguard the world's threatened biodiversity hotspots in developing countries. It is a joint initiative of Conservation International (CI), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. CEPF provides financing to projects in biodiversity hotspots, areas with more than 60 percent of the Earth’s terrestrial species diversity in just 1.4 percent of its land surface. -

First Quarter of 2019

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Macroeconomic Performance . 1 Inflation . 1 Consumer Price Index . 1 Purchasing Power of Peso . 2 Labor and Employment . 2 II. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Sector Performance . 3 Crops . 3 Palay . 3 Corn . 3 Fruit Crops . 4 Vegetables . 4 Non-food and Industrial and Commercial Crops . 5 Livestock and Poultry . 5 Fishery . 6 Forestry . 6 III. Trade and Industry Services Sector Performance . 8 Business Name Registration . 8 Export . 8 Import . 9 Manufacturing . 9 Mining . 10 IV. Services Sector Performance . 11 Financing . 11 Tourism . 12 Air Transport . 12 Sea Transport . 13 Land Transport . 13 V. Peace and Security . 15 VI. Development Prospects . 16 MACROECONOMIC PERFORMANCE Inflation Rate Figure 1. Inflation Rate, Caraga Region The region’s inflation rate continued to move at a slower pace in Q1 2019. From 4.2 percent in December 2018, it declined by 0.5 percentage point in January 2019 at 3.7 percent (Figure 1) . It further decelerated in the succeeding months, registering 3.3 percent in February and 2.9 percent in March. This improvement was primarily due to the slow movement in the monthly increment in the price Source: PSA Caraga indices of heavily-weighted commodity groups, such as food and non-alcoholic beverages; Figure 2. Inflation Rate by Province housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels; and transport. The importation of rice somehow averted the further increase in the market price of rice in the locality. In addition, the provision of government subsidies particularly to vulnerable groups (i.e. DOTr’s Pantawid Pasada Program) and free tuitions under Republic Act No. -

Typhoon Bopha (Pablo)

N MA019v2 ' N 0 ' Silago 3 0 ° 3 0 ° 1 0 Philippines 1 Totally Damaged Houses Partially Damaged Houses Number of houses Number of houses Sogod Loreto Loreto 1-25 2-100 717 376 Loreto Loreto 26-250 101-500 San Juan San Juan 251-1000 501-1000 1001-2000 1001-2000 2001-4000 2001-4000 Cagdianao Cagdianao 1 N ° N San Isidro 0 ° Dinagat 1 0 Dinagat San Isidro Philippines: 1 5 Dinagat (Surigao del Norte) Dinagat (Surigao 5 del Norte) Numancia 280 Typhoon Bopha Numancia Pilar Pilar Pilar Pilar (Pablo) - General 547 Surigao Dapa Surigao Dapa Luna General Totally and Partially Surigao Surigao Luna San San City Francisco City Francisco Dapa Dapa Damaged Housing in 1 208 3 4 6 6 Placer Placer Caraga Placer Placer 10 21 Bacuag Mainit Bacuag (as at 9th Dec 5am) Mainit Mainit 2 N 1 Mainit ' N 0 ' 3 0 ° Map shows totally and partially damaged 3 9 Claver ° 9 Claver housing in Davao region as of 9th Dec. 33 Bohol Sea Kitcharao Source is "NDRRMC sitrep, Effects of Bohol Sea Kitcharao 10 Typhoon "Pablo" (Bopha) 9th Dec 5am". 3 Province Madrid Storm track Madrid Region Lanuza Tubay Cortes ! Tubay Carmen Major settlements Carmen Cortes 513 2 127 21 Lanuza 10 Remedios T. Tandag Tandag City Tandag Remedios T. Tandag City Romualdez 3 Romualdez 15 N ° N 13 9 ° Bayabas 9 Buenavista Sibagat Buenavista Sibagat Bayabas Carmen Carmen Butuan 53 200 Butuan 127 Butuan 21 Butuan 3 City City Cagwait Cagwait 254 Prosperidad 12 17 Gingoog Buenavista 631 Gingoog Buenavista Marihatag Marihatag 43 1 38 19 San Las Nieves San Agustin Las Nieves Agustin 57 Prosperidad 56 2 4 0 10 -

Indigenous Religion, Institutions and Rituals of the Mamanwas of Caraga Region, Philippines

Asian Journal of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities Vol. 1, No.1, 2013 INDIGENOUS RELIGION, INSTITUTIONS AND RITUALS OF THE MAMANWAS OF CARAGA REGION, PHILIPPINES Ramel D. Tomaquin College of Arts and Sciences Surigao del Sur State University Tandag City, Philippines Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Mamanwas, one of the IP communities of Caraga region. Said to be one of the original settlers of Caraga and considered the Negrito group of Mindanao. Only very few literatures and studies written about them. Despite of massive acculturation of other IP groups of the region such the Agusan-Surigao Manobos, the Mansaka/Mandaya, Banwaon, Higaanon and Talaandig. The Mamanwas still on the process of integration to Philippine body-politic. It is in this scenario they were able to retain indigenous religion, institutions and rituals. Thus the study was conducted. It covers on the following sites: Mt. Manganlo in Claver, Lake Mainit in Alegria both Surigao Del Norte, Hitaob in Tandag City, Lubcon and Burgus in Cortes and Sibahay in Lanuza of Surigao Del Sur respectively. The study used ethnographic method with strict adherence of the right of pre- informed consent in accordance with RA 8371 or Indigenous Peoples Right Act of 1997. It can be deduced from the paper that despite of socio- cultural changes of the IP’s of Caraga the Mamanwas were able to retain these practices but for how long? Moreover, socio-cultural change is slowly taking place in the Mamanwa social milieu. Preservation of these worldviews is wanting as a part of national heritage and for posterity. -

NDRRMC Update Progressl Report on the Effects of SLPA in CARAGA

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Center, Camp Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, Quezon City, Philippines NDRRMC UPDATE Progress Report on the Effects of Shallow Low Pressure Area (SLPA) in CARAGA Region Releasing Officer USEC BENITO T. RAMOS Executive Director, NDRRMC and Administrator, OCD DATE: 19 February 2011, 2:00 PM Sources: OCD – CARAGA, Agusan del Sur PIA, PNP and LGU I. SITUATION OVERVIEW Profile of the Incident • Due to Shallow Low Pressure Area (SLPA), CARAGA Region is experiencing cloudy skies but no rain since last night 18 February 2011. The following incidents were observed and monitored: AGUSAN DEL SUR • River systems in the Province of Agusan del Sur are now increasing in water level particularly in Gibong River in Prosperidad and Wawa River in Sibagat • Portion of National Highway in Bunawan, Agusan del Sur is flooded but still passable to heavy vehicles • Few houses in Los Arcos, Prosperidad, Agusan del Sur are still underwater. Road section in the same area is submerged with water but passable. • Pre-emptive evacuations were conducted in the municipalities of San Francisco (Brgys. 1 and 2) and Rosario (Brgys. Poblacion, Libuac and Cabanto). Evacuees are now housed at the Municipal Gym, Agusan del Sur National High School (San Francisco) and Municipal Training Center (Rosario) AGUSAN DEL NORTE • Flights of Cebu Pacific and Philippine Airlines in Butuan City resumed this morning. SURIGAO DEL SUR • Road section from San Vicente to Poblacion, Barobo, Surigao del Sur is now passable to all types of vehicles • Awa-Azpetia-lianga road incurred slip at the side portion with 26 meters length, 5 meters wide and average depth of 3 meters. -

DILEEP 2009-2016 Rona Start.Xls

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT Caraga Regional Office DOLE Integrated Livelihood and Emergency Employment Program(DILEEP) - KABUHAYAN Beneficiaries Grant ACP Beneficiaries Project Title Date Released Female Total Amount Check No. Date AGUSAN DEL NORTE 1 BLGU Sto.Rosario, Rice Trading and Grocery Magallanes, Agusan del Project 162 1,000,000.00 1049449 5/9/2017 May 15, 2017 Norte/Lauan Village Workers Association 2 Eastern Suburb Tricyle Motor Spare Parts and Operators and Drivers Accessories Trading 45 438,693.00 Association (ESTODA) Ampayon, Butuan City 3 BLGU-Dulag,Butuan Rice and Corn Trading City/Dulag Womens 75 750,000.00 1049876 6/30/2017 November 6,2017 Association 4 BLGU-Binuangan, Tubay Consumer Store Agusan del Norte/Binuangan Farmers 25 108,501.00 1049887 6/30/2017 November 7, 2017 and Fisherfolk Association 5 BLGU-Jagupit, Santiago Motor Spare Parts and Agusan del Accessories Trading Norte/Cabadbaran Santiago Tricycle 33 307,700.00 1049886 6/30/2017 November 13, 2017 Operators and Drivers Association (CASATODA) 6 BLGU-Manapa, Milkfish in Marine Cage Buenavista Agusan del Project Norte/Manapa Homebase 35 55 485,350.00 1081421 10/8/2017 November 13, 2017 Workers Association 7 BLGU San Antonio, RTR, Green Charcoal Project Agusan del Norte/Nagkahi-usang 120 120 250,000.00 Kababaihan sa Antonio (NAKSA) 8 BLGU-Mat-i, Las Nieves, SEWING Agusan del Norte/Barangay Mat-i 50 275,000.00 Women's Association (Las Nieves) 9 Mabuhay Small Coconut Rice and Corn Retailing Farmers Association and Wholesaling 25 -

Mines and Geosciences Bureau Caraga Regional Office Consolidated Mineral Resources Data on Sales in Caraga Region Cy-2017

MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU CARAGA REGIONAL OFFICE CONSOLIDATED MINERAL RESOURCES DATA ON SALES IN CARAGA REGION CY-2017 UNIT 2% EXCISE TAX (in 5% ROYALTY TAX (in NO. OF Country of Mineral Commodity/ Mining Company Location Volume Gross Value in US$ Gross Value in Php IP SHARES USED PhP) PhP) SHIPMENTS Destination Gold Philsaga Mining Corp. Bunawan & Rosario, Agusan del Sur kg 2,656.27 116,596,857.36 5,883,703,729.65 117,674,074.59 N/A 22 58,837,037.30 Hong Kong Greenstone Resources Corp. Mainit & Tubod, Surigao del Norte kg 287.06 12,369,409.73 623,303,449.79 12,466,069.00 N/A 3 6,233,034.50 Switzerland TOTAL 2,943.33 128,966,267.09 6,507,007,179.44 130,140,143.59 - 65,070,071.79 Silver Philsaga Mining Corp. Bunawan & Rosario, Agusan del Sur kg 565.25 338,001.75 17,053,051.96 341,061.04 N/A 22 170,530.52 Hong Kong Greenstone Resources Corp. Mainit & Tubod, Surigao del Norte kg 298.97 173,627.79 8,773,551.72 175,471.03 N/A 3 87,735.52 Switzerland TOTAL 864.21 511,629.54 25,826,603.68 516,532.07 - 258,266.04 Nickel Ore Taganito Mining Corp Claver, Surigao del Norte WMT 3,052,122.00 82,390,844.15 4,154,730,095.67 83,094,601.91 207,736,504.78 57 41,547,300.96 Japan and China TMC - THPAL Feed Claver, Surigao del Norte WMT 4,589,953.00 31,288,050.82 1,575,460,958.00 31,509,219.17 78,773,047.90 12 OTPs THPAL Surigao, Phil. -

Medicinal Plants Used by the Manobo Tribe of Prosperidad, Agusan Del Sur, Philippines-An Ethnobotanical Survey

Research Article Medicinal Plants used by the Manobo Tribe of Prosperidad, Agusan Del Sur, Philippines-an Ethnobotanical Survey Lyn Dela Rosa Paraguison1,2,*, Danilo Niem Tandang3, Grecebio Jonathan Duran Alejandro1,4 1The Graduate School, University of Santo Tomas, España Boulevard, Manila, PHILIPPINES. 2College of Science, Biology Department, Adamson University, Ermita, Manila, PHILIPPINES. 3National Museum of the Philippines, Ermita, Manila, PHILIPPINES. 4College of Science and Research Center for the Natural and Applied Sciences, University of Santo Tomas, España Boulevard, Manila, PHILIPPINES. Submission Date: 13-09-2020; Revision Date: 22-11-2020; Accepted Date: 01-12-2020 Correspondence: ABSTRACT Ms. Lyn D Paraguison, 1The Graduate School, Objectives: The Philippine Manobo tribe is historically rich in ethnomedicinal practices and known University of Santo to use local names as “Lunas” (meaning cure) of most medicinal plants. The purpose of this Tomas, España study is to record the traditional practices, use of medicinal plants and information of the Agusan Boulevard, 1015 Manila, Manobo tribe in order to establish the relative significance, consensus and scope of all medicinal PHILIPPINES. 2College of Science, plants used. Methods: Ethnomedicinal survey of medicinal plants was carried out in three selected Biology Department, barangays of Prosperidad City, Agusan del Sur. Ethnomedicinal data were collected through a Adamson University, semi-structured interview, group discussions and guided field walks from 144 primary informants. 900 Ermita, Manila, Plant importance was calculated using indices such as Family importance value (FIV) and relative PHILIPPINES. Phone no: +63-8- 524- frequency of citation (RFC). Results: A total of 40 species belonging to 34 genera and 23 families 2011 LOCAL 210 have been identified as having ethnomedicinal significance. -

A-Ac837e.Pdf

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The word “countries” appearing in the text refers to countries, territories and areas without distinction. The designations “developed” and “developing” countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. The opinions expressed in the articles by contributing authors are not necessarily those of FAO. The EC-FAO Partnership Programme on Information and Analysis for Sustainable Forest Management: Linking National and International Efforts in South Asia and Southeast Asia is designed to enhance country capacities to collect and analyze relevant data, to disseminate up-to- date information on forestry and to make this information more readily available for strategic decision-making. Thirteen countries in South and Southeast Asia (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Lao P.D.R., Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Viet Nam) participate in the Programme. Operating under the guidance of the Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission (APFC) Working Group on Statistics and Information, the initiative is implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in close partnership with experts from participating countries. It draws on experience gained from similar EC-FAO efforts in Africa, and the Caribbean and Latin America and is funded by the European Commission. -

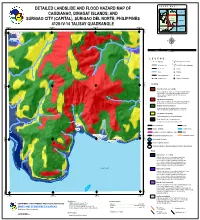

Detailed Landslide and Flood Hazard Map of Cagdianao

II NN DD EE XX MM AA PP :: DETAILED LANDSLIDE AND FLOOD HAZARD MAP OF 125°40'0"E 125°45'0"E 4120-IV-8 4120-IV-9 4120-IV-10 9°55'0"N CAGDIANAO, DINAGAT ISLANDS; AND 9°55'0"N SURIGAO CITY (Capital) SURIGAO CITY (CAPITAL), SURIGAO DEL NORTE, PHILIPPINES CAGDIANAO 4120-IV-13 4120-IV-14 4120-IV-15 4120-IV-14 TALISAY QUADRANGLE 125°39'0"E 125°40'0"E 125°41'0"E 125°42'0"E SURIGAO CITY (Capital) 4120-IV-19 4120-IV-20 4120-IV-18 9°50'0"N 9°50'0"N Purok I Mauswagon (Tigbao) Purok II Malipayon 125°40'0"E # (Tigbao) #n 9°54'0"N 9°54'0"N Purok III (Tigbao) #n Tigbao Elementary School (Tigbao) μ 0120.5 Kilometers LL E G E N D : Main road POBLACIONP! Barangay center location So. Magaling Secondary road (Poblacion)# Purok/Sitio location (Barangay) Track; trail n School River v® Hospital Municipal boundary G Church 80 Contour (meter) Proposed relocation site Landslide 9°53'0"N 9°53'0"N Very high landslide susceptibility Areas usually with steep to very steep slopes and underlain by weak materials. Recent landslides, escarpments and tension cracks are present. Human initiated effects could be an aggravating factor. High landslide susceptibility Areas usually with steep to very steep slopes and underlain by weak materials. Areas with numerous old/inactive landslides. Moderate landslide susceptibility Areas with moderately steep slopes. Soil creep and other indications of possible landslide occurrence are present. Low landslide susceptibility Gently sloping areas with no identified landslide. -

Second Quarter of 2019 Compared to Its Performance on the Same Period Last Year (Figure 1)

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Macroeconomic Performance . 1 Inflation . 1 Consumer Price Index . 1 Purchasing Power of Peso . 2 Labor and Employment . 2 II. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Sector Performance . 3 Crops . 3 Palay . 3 Corn . 4 Fruit Crops . 5 Vegetables . 6 Non-food and Industrial and Commercial Crops . 7 Livestock and Poultry . 7 Fishery . 7 Forestry . 8 III. Trade and Industry Services Sector Performance . 9 Business Name Registration . 9 Export . 9 Manufacturing . 10 Mining . 10 IV. Services Sector Performance . 12 Financing . 12 Tourism . 12 Air Transport . 13 Sea Transport . 13 Land Transport . 14 V. Peace and Security . 16 VI. Development Prospects . 18 MACROECONOMIC PERFORMANCE Inflation Rate Figure 1. Inflation Rate, Caraga Region Page 1 The region’s inflation further eased down in the second quarter of 2019 compared to its performance on the same period last year (Figure 1). On the average, the region’s inflation rate declined by 0.9 percentage point to settle at 2.4 percent in Q2 this year from 3.3 percent in the same period last year. The region’s inflation rate continued to slow down from 2.6 percent in April 2019 to 2.0 percent in June 2019, a decrease of 0.6 percentage point between those Source: PSA Caraga periods. This was attributed to the slow price increases in the overall price indices over time Figure 2. Inflation Rate by Province on the region’s basic goods and services, particularly food items and education. The implementation of Republic Act No. 10931, which provides free tuition, essentially reduced the cost of education in the region.