Views Expressed Are Those of the Email: [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

2020 Submissions

2020 Submissions FEMALE VOCALIST CORINNA SOWERS ADLER Second Stories; Songs from the Heart; Winter Song The Triad, Laurie Beechman, Oakeside Bloomfield Cultural Center LUCILLE CARR-KAFFASHAN How the Light Gets In Don’t Tell Mama CYNTHIA CRANE This Is a Changing World, My Dear Don’t Tell Mama SALLY DARLING And Kurt Weill Begat Kander & Ebb Don’t Tell Mama, Urban Stages DAWN DEROW The House That Built Me Laurie Beechman GOLDIE DVER Back in Mama’s Arms Don’t Tell Mama RENEE KATZ When It Happens to You: Renee Katz Sings Jule Styne; How Can I Keep From Singing Don't Tell Mama, Laurie Beechman ANN KITTREDGE Fancy Meeting You Here; Movie Nite Feinstein’s/54 Below, Urban Stages, Feinstein’s at Vitello's, Beach Cafe ANGELA LEONE Mathis and More Don’t Tell Mama SUSANNE MACK Where I Belong Pangea, Don’t Tell Mama NICCI NICHOLAS Nothin’ Can Be Done Don’t Tell Mama LESLIE OROFINO Shine Don’t Tell Mama, BJ Ryan's Magnolia Room YAEL RASOOLY Glamour in the Dark; Love Must Have an End Laurie Beechman, Don’t Tell Mama WENDY SCHERL Town & Country; You’ll See Laurie Beechman, Davenport’s, BJ Ryan's Magnolia Room JILL SENTER Celebrate the Moment Laurie Beechman - 1 - MAUREEN KELLEY STEWART There Will Never Be Another You: The Songs of Harry Warren; A Gershwin Sampler; Everything’s Coming Up Roses: The Music of Jule Styne Laurie Beechman, Mohonk Mountain House, Sharon Country Club, Spencertown Academy Art Center MAUREEN TAYLOR Cosmic Connections: The Lyrics of Michael Colby Don’t Tell Mama STEPHANIE TRUDEAU Chavela: Think of Me Don’t Tell Mama LISA VIGGIANO From Lady Day to The Boss Pangea, Don’t Tell Mama ROBIN WESTLE In the Summer of ‘69 Don’t Tell Mama AMY BETH WILLIAMS Meet Me at the Bar Don’t Tell Mama MALE VOCALIST ARI AXELROD A Celebration of Jewish Broadway Birdland Theater, The Kranzberg (St. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

MUNI 20151109 – Evergreeny 06 (Thomas „Fats“ Waller, Victor Young)

MUNI 20151109 – Evergreeny 06 (Thomas „Fats“ Waller, Victor Young) Honeysuckle Rose – dokončení z minulé přednášky Lena Horne 2:51 First published 1957. Nat Brandwynne Orchestra, conducted by Lennie Hayton. SP RCA 45-1120. CD Recall 305. Velma Middleton-Louis Armstrong 2:56 New York, April 26, 1955. Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars. LP Columbia CL 708. CD Columbia 64927 Ella Fitzgerald 2:20 Savoy Ballroom, New York, December 10, 1937. Chick Webb Orchestra. CD Musica MJCD 1110. Ella Fitzgerald 1:42> July 15, 1963 New York. Count Basie and His Orchestra. LP Verve V6-4061. CD Verve 539 059-2. Sarah Vaughan 2:22 Mister Kelly‟s, Chicago, August 6, 1957. Jimmy Jones Trio. LP Mercury MG 20326. CD EmArcy 832 791-2. Nat King Cole Trio – instrumental 2:32 December 6, 1940 Los Angeles. Nat Cole-piano, Oscar Moore-g, Wesley Prince-b. 78 rpm Decca 8535. CD GRP 16622. Jamey Aebersold 1:00> piano-bass-drums accompaniment. Doc Severinsen 3:43 1991, Bill Holman-arr. CD Amherst 94405. Broadway-Ain‟t Misbehavin‟ Broadway show. Ken Page, Nell Carter-voc. 2:30> 1978. LP RCA BL 02965. Sweet Sue, Just You (lyrics by Will J. Harris) - 1928 Fats Waller and His Rhythm: Herman Autrey-tp; Rudy Powell-cl, as; 2:55 Fats Waller-p,voc; James Smith-g; Charles Turner-b; Arnold Boling-dr. Camden, NJ, June 24, 1935. Victor 25087 / CD Gallerie GALE 412. Beautiful Love (Haven Gillespie, Wayne King, Egbert Van Alstyne) - 1931 Anita O’Day-voc; orchestra arranged and conducted by Buddy Bregman. 1:03> Los Angeles, December 6, 1955. -

Music Quiz Questions

Music Quiz Questions Check the box for all answers or click on each question for its answer. New! is an addition in the last month. 157. Though denied by its author as the source of his inspiration, what musical work has strong resemblance to the story of a mythical village called Germelshausen that fell under a curse and appears for only one day every century? Brigadoon by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe The story involves two American tourists who stumble upon Brigadoon, a mysterious Scottish village that appears for only one day every hundred years. Tommy, one of the tourists, falls in love with Fiona, a young woman from Brigadoon. Lerner, however, denied that he had based the book on an older story and stated that he didn't learn of the existence of the Germelshausen story until after he had completed the first draft of Brigadoon. 156. In December 1971, Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention were playing in a concert when the casino venue they were in caught fire due to an over-zealous member of the audience firing a a flare gun into the rattan covered ceiling. This is the true origin story of what rock classic? "Smoke on the Water" by Deep Purple The resulting fire destroyed the entire casino complex, along with all the Mothers' equipment. The "smoke on the water" that became the title of the song (credited to bass guitarist Roger Glover, who related how the title occurred to him when he suddenly woke from a dream a few days later) referred to the smoke from the fire spreading over Lake Geneva from the burning casino as the members of Deep Purple watched the fire from their hotel. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Read an Excerpt

ACROSS THE PLAINS The Journey of the Palace Wagon Family by SANDRA FENlCHEL ASHER Dramatic Publishing Wcxxlstock, lllinois • London, England • Melooume, Australia © The Dramatic Publishing Company, Woodstock, Illinois *** NOTICE *** TIle amaleur and stock acting rights to this wen: are controlled exclusively by TIm DRAMATIC PUBUSHING COMPANY without wha;e pennission in writing 00 performance of it may be given. Royalty fees are given in our current catalogue and are subject to change without notice. Royalty must be paid every time a play is perfonned whether or not it is JI=lted for profit and whether a- not admission is charged. A play is perfonned any time it is acted bef<re an audience. All inquiries conceming amateur and stock rights should be addressed to: DRAMATIC PUBUSlllNG P. O. Box 129, Woodstock, lliioois 60098. COPYRIGHT UW GWES THE AUTHOR OR THE AUTHOR'S AGENT THE EXCLUSIVE RIGHT TO MAKE COPIES. This law provides lIlIlhcrs with a fair return fa- their creative efforts. Authas earn their living from the royalties they receive fnm book sales and from the perfonnance of their work Conscientious offiervance ofcopyright law is not ooly ethical, it encour ages authors to continue their creative work. This wa-k is fully protected by copyright No altecations, deletions a- substitutions may be made in the work without the pria- written consent of the publisher. No part of this work may be reproduced a- ttansmitted in any form or by any means, electrooic or me chanical, including photocopy, recording, videotape, film, or any information storage and retrieval system, without pennission in writing from the publisher. -

Pioneers of the Concept Album

Fancy Meeting You Here: Pioneers of the Concept Album Todd Decker Abstract: The introduction of the long-playing record in 1948 was the most aesthetically signi½cant tech- nological change in the century of the recorded music disc. The new format challenged record producers and recording artists of the 1950s to group sets of songs into marketable wholes and led to a ½rst generation of concept albums that predate more celebrated examples by rock bands from the 1960s. Two strategies used to unify concept albums in the 1950s stand out. The ½rst brought together performers unlikely to col- laborate in the world of live music making. The second strategy featured well-known singers in song- writer- or performer-centered albums of songs from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s recorded in contemporary musical styles. Recording artists discussed include Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney, among others. After setting the speed dial to 33 1/3, many Amer- icans christened their multiple-speed phonographs with the original cast album of Rodgers and Hammer - stein’s South Paci½c (1949) in the new long-playing record (lp) format. The South Paci½c cast album begins in dramatic fashion with the jagged leaps of the show tune “Bali Hai” arranged for the show’s large pit orchestra: suitable fanfare for the revolu- tion in popular music that followed the wide public adoption of the lp. Reportedly selling more than one million copies, the South Paci½c lp helped launch Columbia Records’ innovative new recorded music format, which, along with its longer playing TODD DECKER is an Associate time, also delivered better sound quality than the Professor of Musicology at Wash- 78s that had been the industry standard for the pre- ington University in St. -

FOLLOWING the HERD REPERTOIRE TABLE 2017-V3

TITLE COMPOSER/ STYLE ALBUM/ERA INSTRUMENT ARRANGER FEATURE/SOLO ADAM’S BROADBENT MEDIUM BRAND NEW 1971 CLARINET/FLUGEL APPLE SWING TROMBONE AFTER PARISH/PIERCE SLOW BRAND NEW 1971 PIANO HOURS GROOVE AFTER CREAMER/LAYTON/ HOLMAN UP TEMPO WOODY HERMAN 1964 CLARINET/TRUMPET YOU’VE TENOR SAX GONE AJA BECKER/FAGAN / BROADBENT STRAIGHT CHICK,DONALD,WALTER TENOR SAX 8th WOODROW 1978 A KISS HEMAN/SLACK/VICTOR EASY NUMEROUS ALBUMS TRUMPET/CLARINET GOODNIGHT VOCAL SINCE 1945 ALONE AGAIN O’SULLIVAN/ BROADBENT STRAIGHT THE RAVEN SPEAKS TROMBONE/ALTO SAX (NATURALLY) 8th 1974 TENOR SAX AMERICA ZAPPA/BROADBENT FAST THUNDERING HERD FLUGEL/PIANO DRINKS AND GOES HOME SWING 1974 APPLE WOODY HERMAN UP TEMPO NUMEROUS ALBUMS VIBES/’BONE /TENOR SAX/ HONEY SINCE 1944 TRUMPET APRIL DeSYLVA/SILVERS/BURNS EASY JAZZ SWINGER ALBUM FLUGEL HORN SHOWERS VOCAL 1966 AQUARIUS RADA/RAGNI STRAIGHT HEAVY EXPOSURE 1969 SOPRANO SAX EVANS 8th A SONG FOR RUSSELL/STAPLETON STRAIGHT GIANT STEPS PIANO/SOPRANO SAX YOU 8th 1973 FLUGEL AURORA ROLAND BALLAD VARIOUS ALBUMS ALTO/TENOR AUTOBAHN BURNS/HERMAN MEDIUM VARIOUS ALBUMS TENOR/BARITONE BLUES SWING SINCE 1954 TRUMPET BAMBA BYRD/FELLER MEDIUM WOODY HERMAN Vol. 3 GUITAR LATIN/SWING SAMBA BASS FOLK CLARKE/KLATKA FAST 4 THUNDERING HERDS BASS/PIANO/PICCOLO (ROCK-FUNK) SONG 1974 BATTLE ELLINGTON/FEDCHOCK UP-TEMPO GOLD STAR SAXES ROYAL SWING 1987 BEBOP AND BROADBENT FAST GIANT STEPS 1973 TRUMPET/’BONE/TENOR ROSES SWING SAX BEDROOM GEE/PIERCE EASY LIVE AT HARRAH’S CLUB PIANO/TROMBONE EYES SWING 1964 TRUMPET BETTER GET MINGUS/ HAMMER FAST -

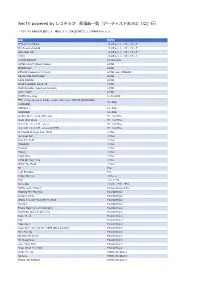

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Subjugation IV

Subjugation 4 Tribulation by Fel (aka James Galloway) ToC 1 To: Title ToC 2 Chapter 1 Koira, 18 Toraa, 4401, Orthodox Calendar Wednesday, 28 January 2014, Terran Standard Calendar Koira, 18 Toraa, year 1327 of the 97th Generation, Karinne Historical Reference Calendar Foxwood East, Karsa, Karis Amber was starting to make a nuisance of herself. There was just something intrinsically, fundamentally wrong about an insufferably cute animal that was smart enough to know that it was insufferably cute, and therefore exploited that insufferable cuteness with almost ruthless impunity. In the 18 days since she’d arrived in their house, she’d quickly learned that she could do virtually anything and get away with it, because she was, quite literally, too cute to punish. Fortunately, thus far she had yet to attempt anything truly criminal, but that didn’t mean that she didn’t abuse her cuteness. One of the ways she was abusing it was just what she was doing now, licking his ear when he was trying to sleep. Her tiny little tongue was surprisingly hot, and it startled him awake. “Amber!” he grunted incoherently. “I’m trying to sleep!” She gave one of her little squeaking yips, not quite a bark but somewhat similar to it, and jumped up onto his shoulder. She didn’t even weigh three pounds, she was so small, but her little claws were like needles as they kneaded into his shoulder. He groaned in frustration and swatted lightly in her general direction, but the little bundle of fur was not impressed by his attempts to shoo her away.