North and South Korea: Division by Constructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. Bennett C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Preparing for the Possibility of a North Korean Collapse Bruce W. -

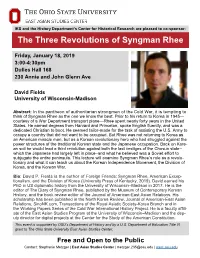

The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee

IKS and the History Department’s Center for Historical Research are pleased to co-sponsor: The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee Friday, January 18, 2019 3:00-4:30pm Dulles Hall 168 230 Annie and John Glenn Ave David Fields University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract: In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen of the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945— courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of assisting the U.S. Army to occupy a country that did not want to be occupied. But Rhee was not returning to Korea as an American miracle man, but as a Korean revolutionary hero who had struggled against the power structures of the traditional Korean state and the Japanese occupation. Back on Kore- an soil he would lead a third revolution against both the last vestiges of the Chosun state– which the Japanese had largely left in place–and what he believed was a Soviet effort to subjugate the entire peninsula. This lecture will examine Syngman Rhee’s role as a revolu- tionary and what it can teach us about the Korean Independence Movement, the Division of Korea, and the Korean War. Bio: David P. Fields is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Excep- tionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). -

Marxism, Stalinism, and the Juche Speech of 1955: on the Theoretical De-Stalinization of North Korea

Marxism, Stalinism, and the Juche Speech of 1955: On the Theoretical De-Stalinization of North Korea Alzo David-West This essay responds to the argument of Brian Myers that late North Korean leader Kim Il Sung’s Juche speech of 1955 is not nationalist (or Stalinist) in any meaningful sense of the term. The author examines the literary formalist method of interpretation that leads Myers to that conclusion, considers the pro- grammatic differences of orthodox Marxism and its development as “Marx- ism-Leninism” under Stalinism, and explains that the North Korean Juche speech is not only nationalist, but also grounded in the Stalinist political tradi- tion inaugurated in the Soviet Union in 1924. Keywords: Juche, Nationalism, North Korean Stalinism, Soviet Stalinism, Socialism in One Country Introduction Brian Myers, a specialist in North Korean literature and advocate of the view that North Korea is not a Stalinist state, has advanced the argument in his Acta Koreana essay, “The Watershed that Wasn’t” (2006), that late North Korean leader Kim Il Sung’s Juche speech of 1955, a landmark document of North Korean Stalinism authored two years after the Korean War, “is not nationalist in any meaningful sense of the term” (Myers 2006:89). That proposition has far- reaching historical and theoretical implications. North Korean studies scholars such as Charles K. Armstrong, Adrian Buzo, Seong-Chang Cheong, Andrei N. Lankov, Chong-Sik Lee, and Bala、zs Szalontai have explained that North Korea adhered to the tactically unreformed and unreconstructed model of nationalist The Review of Korean Studies Volume 10 Number 3 (September 2007) : 127-152 © 2007 by the Academy of Korean Studies. -

Effective Evangelistic Strategies for North Korean Defectors (Talbukmin) in South Korea

ABSTRACT Effective Evangelistic Strategies for North Korean Defectors (Talbukmin) in South Korea South Korean churches eagerness for spreading the gospel to North Koreans is a passion. However, because of the barriers between the two Koreas, spreading the Good News is nearly impossible. In the middle of the 1990’s, numerous North Koreans defected to China to avoid starvation. Many South Korean missionaries met North Koreans directly and offered the gospel along with necessities for survival in China. Since the early of 2000’s, many Talbukmin have entered South Korea so South Korean churches have directly met North Koreans and spread the gospel. However, the fruits of evangelism are few. South Korean churches find that Talbukmin are very different from South Koreans in large part due to the sixty-year division. South Korean churches do not know or fully understand the characteristics of the Talbukmin. The evangelism strategies and ministry programs of South Korean churches, which are designed for South Koreans, do not adapt well to serve the Talbukmin. This research lists and describes the following five theories to be used in the development of the effective evangelistic strategies for use with the Talbukmin and for use to interpret the interviews and questionnaires: the conversion theory, the contextualization theory, the homogenous principle, the worldview transformation theory, and the Nevius Mission Plan. In the following research exploration of the evangelization of Talbukmin in South Korea occurs through two major research agendas. The first agenda is concerned with the study of the characteristics of Talbukmin to be used for the evangelists’ understanding of the depth of differences. -

"Mostly Propaganda in Nature": Kim Il Sung, the Juche Ideology, and The

NORTH KOREA INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTATION PROJECT WORKING PAPER #3 THE NORTH KOREA INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTATION PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and James F. Person, Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the North Korea International Documentation Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 2006 by a grant from the Korea Foundation, and in cooperation with the University of North Korean Studies (Seoul), the North Korea International Documentation Project (NKIDP) addresses the scholarly and policymaking communities’ critical need for reliable information on the North Korean political system and foreign relations by widely disseminating newly declassified documents on the DPRK from the previously inaccessible archives of Pyongyang’s former communist allies. With no history of diplomatic relations with Pyongyang and severely limited access to the country’s elite, it is difficult to for Western policymakers, journalists, and academics to understand the forces and intentions behind North Korea’s actions. The diplomatic record of North Korea’s allies provides valuable context for understanding DPRK policy. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a section in the periodic Cold War International History Project BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to North Korea in the Cold War; a fellowship program for Korean scholars working on North Korea; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. The NKIDP Working Paper Series is designed to provide a speedy publications outlet for historians associated with the project who have gained access to newly- available archives and sources and would like to share their results. -

Welcome to Korea Day: from Diasporic to Hallyu Fan-Nationalism

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 3764–3780 1932–8036/20190005 Welcome to Korea Day: From Diasporic to Hallyu Fan-Nationalism IRINA LYAN1 University of Oxford, UK With the increasing appeal of Korean popular culture known as the Korean Wave or hallyu, fans in Israel among Korean studies students have joined—and even replaced— ethnic Koreans in performing nationalism beyond South Korea’s borders, creating what I call hallyu fan-nationalism. As an unintended consequence of hallyu, such nationalism enables non-Korean hallyu fans to take on the empowering roles of cultural experts, educators, and even cultural ambassadors to promote Korea abroad. The symbolic shift from diasporic to hallyu nationalism brings to the fore nonnationalist, nonessentialist, and transcultural perspectives in fandom studies. In tracing the history of Korea Day from the 2000s to the 2010s, I found that hallyu fan-students are mobilized both by the macro mission to promote a positive image of Korea in their home societies and by the micro motivation to repair their own, often stigmatized, self-image. Keywords: transcultural fandom studies, hallyu, Korean Wave, Korean studies, Korea Day, diasporic nationalism While talking with Israeli students enrolled in Korean studies (mostly female fans of Korean popular culture) in an effort to understand their motivations behind organizing Korea Day and promoting Korean culture in Israel in general, I was surprised when some of them used the Hebrew word hasbara, which literally translates as “explanation.” As a synonym for propaganda, hasbara refers to the public diplomacy of Israel that aims to promote a positive image of Israel to the world and to counter its delegitimization. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

Thank You, Father Kim Il Sung” Is the First Phrase North Korean Parents Are Instructed to Teach to Their Children

“THANK YOU FATHER KIM ILLL SUNG”:”:”: Eyewitness Accounts of Severe Violations of Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Religion in North Korea PPPREPARED BYYY: DAVID HAWK Cover Photo by CNN NOVEMBER 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Michael Cromartie Chair Felice D. Gaer Vice Chair Nina Shea Vice Chair Preeta D. Bansal Archbishop Charles J. Chaput Khaled Abou El Fadl Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Bishop Ricardo Ramirez Ambassador John V. Hanford, III, ex officio Joseph R. Crapa Executive Diretor NORTH KOREA STUDY TEAM David Hawk Author and Lead Researcher Jae Chun Won Research Manager Byoung Lo (Philo) Kim Research Advisor United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Staff Tad Stahnke, Deputy Director for Policy David Dettoni, Deputy Director for Outreach Anne Johnson, Director of Communications Christy Klaasen, Director of Government Affairs Carmelita Hines, Director of Administration Patricia Carley, Associate Director for Policy Mark Hetfield, Director, International Refugee Issues Eileen Sullivan, Deputy Director for Communications Dwight Bashir, Senior Policy Analyst Robert C. Blitt, Legal Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Scott Flipse, Senior Policy Analyst Mindy Larmore, Policy Analyst Jacquelin Mitchell, Executive Assistant Tina Ramirez, Research Assistant Allison Salyer, Government Affairs Assistant Stephen R. Snow, Senior Policy Analyst Acknowledgements The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom expresses its deep gratitude to the former North Koreans now residing in South Korea who took the time to relay to the Commission their perspectives on the situation in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and their experiences in North Korea prior to fleeing to China. -

The K-Pop Wave: an Economic Analysis

The K-pop Wave: An Economic Analysis Patrick A. Messerlin1 Wonkyu Shin2 (new revision October 6, 2013) ABSTRACT This paper first shows the key role of the Korean entertainment firms in the K-pop wave: they have found the right niche in which to operate— the ‘dance-intensive’ segment—and worked out a very innovative mix of old and new technologies for developing the Korean comparative advantages in this segment. Secondly, the paper focuses on the most significant features of the Korean market which have contributed to the K-pop success in the world: the relative smallness of this market, its high level of competition, its lower prices than in any other large developed country, and its innovative ways to cope with intellectual property rights issues. Thirdly, the paper discusses the many ways the K-pop wave could ensure its sustainability, in particular by developing and channeling the huge pool of skills and resources of the current K- pop stars to new entertainment and art activities. Last but not least, the paper addresses the key issue of the ‘Koreanness’ of the K-pop wave: does K-pop send some deep messages from and about Korea to the world? It argues that it does. Keywords: Entertainment; Comparative advantages; Services; Trade in services; Internet; Digital music; Technologies; Intellectual Property Rights; Culture; Koreanness. JEL classification: L82, O33, O34, Z1 Acknowledgements: We thank Dukgeun Ahn, Jinwoo Choi, Keun Lee, Walter G. Park and the participants to the seminars at the Graduate School of International Studies of Seoul National University, Hanyang University and STEPI (Science and Technology Policy Institute). -

A Brief of the Korea History

A Brief of the Korea History Chronicle of Korea BC2333- BC.238- 918- 1392- 1910- BC57-668 668-918 1945- BC 108 BC1st 1392 1910 1945 Nangrang Dae GoGuRyeo BukBuYeo Unified GoRyeo JoSun Japan- Han DongBuYeo BaekJae Silla Invaded Min JolBonBuYe Silla BalHae Gug o GaRa (R.O.K DongOkJeo (GaYa) Yo Myng Korea) GoJoSun NamOkJeo Kum Chung (古朝鮮) BukOkJeo WiMan Won Han-5- CHINA Gun SamHan (Wae) (Wae) (IlBon) (IlBon) (IlBon) (Wae) (JAPAN) 1 한국역사 연대기 BC2333- BC.238- BC1세기- 918- 1392- 1910- 668-918 1945- BC 238 BC1세기 668 1392 1910 1945 낙 랑 국 북 부 여 고구려 신 라 고 려 조선 일제강 대한민 동 부 여 신 라 발 해 요 명 점기 국 졸본부여 백 제 금 청 동 옥 저 고조선 가 라 원 중국 남 옥 저 (古朝鮮) (가야) 북 옥 저 위 만 국 한 5 군 (왜) (왜) (일본) (일본) (일본) (일본) 삼 한 (왜) 국가계보 대강 (II) BC108 918 BC2333 BC194 BC57 668 1392 1910 1945 고구려 신 라 고조선(古朝鮮) 부여 옥저 대한 백 제 동예 고려 조선 민국 BC18 660 2 3 1 GoJoSun(2333BC-108BC) 2 Three Kingdom(57BC-AD668) 3 Unified Shilla(668-935) / Balhae 4 GoRyeo(918-1392) 5 JoSun(1392-1910) 6 Japan Colony(1910-1945) 7 The Division of Korea 8 Korea War(1950-1953) 9 Economic Boom In South Korea 1. GoJoSun [고조선] (2333BC-108BC) the origin of Korea n According to the Dangun creation mythological Origin n Dangun WangGeom establish the old JoSun in Manchuria. n The national idea of Korea is based on “Hong-ik-in-gan (弘益人間)”, Devotion the welfare of world-wide human being n DanGun JoSun : 48 DanGuns(Kings) + GiJa JoSun + WeeMan JoSun 4 “고조선의 강역을 밝힌다”의 고조선 강역 - 저자: 윤내현교수, 박선희교수, 하문식교수 5 Where is Manchuria 2.