Kosovo): “Inside Insights” on Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Fifth Periodical Report Presented to the Secretary General of The

Strasbourg, 6 June 2019 MIN-LANG (2019) PR 2 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Fifth periodical report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter MONTENEGRO 1 MONTENEGRO Address: Bulevar Svetog Petra Cetinjskog 130, Ministry of Human 81000 Podgorica, and Minority Rights Montenegro tel: +382 20 234 193 fax: +382 20 234 198 www.minmanj.gov.me DIRECTORATE FOR PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF RIGHTS OF MINORITY NATIONS AND OTHER MINORITY NATIONAL COMMUNITIES THE FIFTH REPORT OF MONTENEGRO ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Podgorica, May 2019 Introductory part 2 Human rights in Montenegro are guaranteed and protected by the Constitution of Montenegro, laws and other regulations adopted in accordance with the Constitution, while ensuring the highest level of respect for international standards in the area of implementation and protection of human rights and freedoms. The Constitution devotes great attention to protecting the identity of minority nations and other minority national communities to which are guaranteed the rights and freedoms that can be used individually and in community with others. Montenegro is constitutionally defined as a civil, democratic, ecological and state of social justice, based on the rule of law. The holder of sovereignty is a citizen who has Montenegrin citizenship. The Constitution of Montenegro provides the legal basis for the promotion, strengthening and enhancement of the protection of fundamental human rights and freedoms and confirms Montenegro's obligation to respect international standards in that context. The Constitution of Montenegro (Official Gazette of Montenegro, No. -

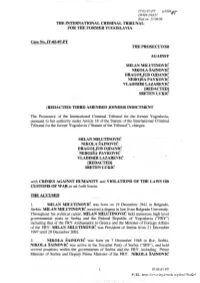

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

IT-05-87-PT p.640"ff( D6404-D6337 . filed on: 21106106 THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Case No.IT-OS-87-PT THE PROSECUTOR AGAINST MILAN MILUTINOVIC NIKOLA SAINOVIC DRAGOLJUB OJDANIC NEBOJSA PA VKOVIC VLADIMIR LAZARE VIC [REDACTED] SRETEN LUKIC (REDACTED) THIRD AMENDED JOINDER INDICTMENT The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, pursuant to her authority under Article 18 of the Statute of the Interiultional Ciiminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia ("Statute of the Tribunal"), charges: MILAN MILUTINOVIC NIKOLA SAINOVIC DRAGOLJUB OJDANIC NEBOJSA PAVKOVIC VLADIMIR LAZAREVIC '.' It [REDACTED] SRETEN LUKIC with CRIMES AGAINST miMANITYand VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OR CUSTOMS, OF- .WAR ' .- as set forth herein... THE ACCUSED 1. MILAN MILUTINOVIC was born on 19 December 1942 in Belgrade, Serbia. MILAN MILUTINOVIC rec(1iveda degreein law from Belgrade University. , ••• ' ", " J ' , • I' " , Throughout his political career, MILAN' l\1ILUTINOVIC held numerous high level governmental posts in Serbia ~d the F~deraI Republic .of Yugoslavia, ("FRY") including that of ,the FRY Ambassador to GreeGe ahd the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the FRY. MILAN MILUTINOVIC was Presiqent of Serbia from 21 December 1997 until 29 December 2002. 2. NIKOLA SAINOVICwas 'born :on '7 December 1948 in Bor, Serbia. NIKOLA SAINOVIC was active in the Socialist Party of Serbia ("SPS"), and held several positions within, the governments of Serbia and the FRY, including Prime Minister of' Serbia' and Deptity Prime Minister of 'the FRY. NIKOLA SAINOVIC 1 IT-05-87-PT PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/33bd2e/ ,.,' " , l' - ---~,.~ ..!..---..--~,.---,---- IT-05-87-PT p,6403 served as Deputy Prini~Minister of the'FRY from February 1994 until on or about 4 November 2000, when a new Federal Government was formed, 3. -

Why Interfaith in Kosovo?

AS WE ARE AS WE ARE THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC KOSOVO AFFAIRS THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN STORIES OLD AND NEW OF A COUNTRY IN THE MAKING AS WE ARE 3 Free to love We are building our own country, nourishing a population of 70% younger than 35, run by a women president in a place where everyone is free to love. AS WE ARE AS WE ARE Stories from a country in the making - The material in this book has been collected, created and edited for the sole purpose of offering an overview and promoting Kosovo’s history, art, culture, education and science. Photos published in this book are submitted by participants in #instakosova #instakosovo competition, selected from the archives of Kosovo photographers, and others are withdrawn from UNESCO website, Database of Cultural Heritage in Kosovo, Wikimedia Commons, illyria. proboards.com and gjakovasummerschool.com This book is not intended for sale. CREDITS AS WE ARE is produced and published under the guidance and for The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kosovo in support of its efforts in joining UNESCO Title: AS WE ARE Stories old and new of a country in the making All rights: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kosovo Publisher: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kosovo / Petrit Selimi Editor: Fiona Kelmendi, Rina Meta Design: Nita Salihu, Trembelat Type: Ekstropia by Yll Rugova, Trembelat Cover picture: Blerta Kambo Printing: ViPrint July 2015 Prishtina, Kosovo kosovoinunesco.com mfa-ks.net instakosova.com interfaithkosovo.com STORIES OLDANDNEWOFACOUNTRYINTHEMAKING STORIES 5 AS WE ARE CONTENT THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC KOSOVO AFFAIRS THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN STORIES OLD AND NEW OF A COUNTRY IN THE MAKING CONTENT 7 AS WE ARE 12—17 Evolving Stories old and new! The past is history, today Kosovo is looking forward to join the world primary organization of education, science and culture to help break the long isolation and to engage in exchange with the rest of the world, starting from 2015 on the 70th Anniversary of UNESCO. -

![I;-OS-G:{-PT ';])JKXXJ -L)3'F.3~ P.4 000 .4R 05 Flpiij4- Out:Ls Fj' the INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL Trffiunal for the FORMER YUGOSLAVIA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7636/i-os-g-pt-jkxxj-l-3f-3-p-4-000-4r-05-flpiij4-out-ls-fj-the-international-criminal-trffiunal-for-the-former-yugoslavia-6187636.webp)

I;-OS-G:{-PT ';])JKXXJ -L)3'F.3~ P.4 000 .4R 05 Flpiij4- Out:Ls Fj' the INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL Trffiunal for the FORMER YUGOSLAVIA

I;-OS-g:{-PT ';])JKXXJ -l)3'f.3~ p.4 000 .4r 05 flPIIJ4- oUt:lS fJ' THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRffiUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Case No. IT·05·87·PT THE PROSECUTOR AGAINST MILAN MILUTINOVIC NIKOLA SAINOVIC DRAGOLJUB OJDANIC NEBOJSA PAVKOVIC VLADIMIR LAZAREVIC VLASTIMIR DORDEVIC SRETEN LUKIC SECOND AMENDED JOINDER INDICTMENT The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the fonner Yugoslavia, pursuant to her authority under Article 18 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the fonner Yugoslavia ("Statute of the Tribunal"), charges: MILAN MILUTINOVIC NIKOLA SAINOVIC DRAGOLJUB OJDANIC NEBOJSA PAVKOVIC VLADIMIR LAZAREVIC VLASTIMIR DORDEVIC SRETEN LUKIC with CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY and VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OR CUSTOMS OF WAR as set forth herein. THE ACCUSED 1. MILAN MILUTINOVIC was born on 19 December 1942 in Belgrade, Serbia. MILAN MILUTINOVIC received ,a degree in law from Belgrade University. Throughout his political career, MILAN MlLUTINOVIC held numerous high level governmental posts in Serbia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia ("FRY") including that of the FRY Ambassador to Greece and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the FRY. MILAN MILUTINOVIC was President of Serbia from 21 December 1997 until 29 December 2002. 2. NIKOLA SAINOVIC was born on 7 December 1948 in Bor, Serbia. NIKOLA SAINOVIC was active in the Socialist Party of Serbia ("SPS"), and held several positions within the governments of Serbia and the FRY, including Prime Minister of Serbia and Deputy Prime Minister of the FRY. NIKOLA SAINOVIC 1 IT-05-87-PT IT-05~87-PT p.3999 served as Deputy Prime Minister of the FRY from February 1994 until on or about 4 November 2000, when a new Federal Government was fonned. -

Mosques,Beautifulski Resorts Andothernat- ESCO World Heritage Sites of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Kosovo Alsohasalot to Offer to Theworld

AS WE ARE AS WE ARE THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF THE REPUBLIC KOSOVO AFFAIRS THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN STORIES OLD AND NEW OF A COUNTRY THRIVING AS WE ARE 3 Free to love We are building our own country, nourishing a population of 70% younger than 35, led by a female president in a place where everyone is free to love. AS WE ARE AS WE ARE Stories old and new of a country thriving - The material in this book has been collected, created and edited for the sole purpose of offering an overview and promoting Kosovo’s history, art, culture, education and science. ‘AS WE ARE / Stories old and new of a country thriving’ includes material previously published in July 2015 under the name ‘AS WE ARE / Stories old and new of a country in the making’. Both books feature the diplomatic efforts of The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in lobbying for Kosovo’s acceptance in UNESCO. The republished work in this edition reinforces these efforts and insists on the unique values that Kosovo has to offer. Photos published in this book are submitted by participants in #instakosova #instakosovo competition, selected from the archives of Kosovo photographers, and others are withdrawn from UNESCO website, Database of Cultural Heritage in Kosovo, Wikimedia Commons and other promotional websites of the same will. This book is not intended for sale. CREDITS AS WE ARE is produced and published under the guidance and for The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kosovo in support of its efforts in joining UNESCO Title: AS WE ARE Stories old and new of a country -

Crc-Journal No 8-9, April – November, 2018

CRC-JOURNAL NO 8-9, APRIL – NOVEMBER, 2018 www.crc-journal.com 1 CRC-JOURNAL NO 8-9, APRIL – NOVEMBER, 2018 CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH CENTER – J o u r n a l International Journal of Social and Human science s E d i t o r - in- C h i e f : Metodi Shamo v , P h D E d i t o r s : , Ibish Mazreku , P h D Elitza Kumanova , Qashif Bakiu, PhD Publisher: Contemporary Research Cente r International Editorial Board: Francis Balle, prof. dr., ’Université Paris II Panthéon-Assas, R. France, Stanford University USA Dimitar Bechev, Visiting Senior Fellow, European Institute (LSEE – Research of South Eastern Europe), London School of Economics; Oxford University, Great Britain, Lachezar Dachev, prof. dr., Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”, R. Bulgaria, “Angel Kanchev” University of Ruse, R. Bulgaria Michael Schulz, Ph.D. SCHOOL OF GLOBAL STUDIES, Associate Professor in Peace and Development Research, University of Gothenburg Mehmet Can, prof. dr. International University of Saraevo, R. Bosnia and Hercegovina, Ibish Mazreku, PhD, University Haxhi Zeka, R. Kosovo Orhan Çeku, PhD, Universiteti “Pjeter Budi”, R. Kosovo Sibel Kibar, Phd, Kastamonu University, R. Turkey Jorida Frakulli, PhD, Albanian University, R. Albania Genta Skurra, PhD, Tirana University, R. Albania Halit Shabani, PhD, University Haxhi Zeka, R. Kosovo Dragana Ranđelović, International University of Novi Pazar, R. Serbia Bajram Çupi, PhD, University of Tetova, R. Macedonia Ylber Sela, PhD, University of Tetova, R. Macedonia Qashif Bakiu, PhD, University of Tetova, R. Macedonia Metodi