1 December 3, 2015 COMING to TERMS: AN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOCIAL STUDIES 11 Examination Questions

SOCIAL STUDIES 11 Examination Questions PART A: Multiple Choice 1. Who is the Queen’s representative in British Columbia? A. Premier B. Senator C. Legislative Assembly D. Lieutenant Governor 2. Which of the following responsibilities belong to the municipal level of government in Canada? A. currency B. criminal law C. school policy D. garbage collection 3. Canada is a representative democracy. What does this mean? A. Canadians elect representative to make decisions on their behalf. B. Canadians appoint members of Parliament to decide on important issues. C. The House of Lords consists of representatives from all provinces and territories to make decisions for all Canadians. D. The Queen is Queen of Canada and appoints the Prime Minister to lead the House of Representatives. 4. How often must federal elections be held in Canada? A. Every five years. B. Every four years. C. At the discretion of the Prime Minister and Governor General. D. Every four to six years depending on the popularity of the government. 5. What is the meaning of cabinet solidarity in the Canadian government system? A. Cabinet ministers must follow the advice of their departments. B. Cabinet ministers must agree on all issues at cabinet meetings. C. Cabinet ministers are allowed to freely express their opinions on all issues during cabinet meetings. D. Cabinet ministers agree publicly on all issues. 6. During which stage does a bill pass into law in Canada? A. Committee stage B. the Senate vote C. the Third and final reading D. Royal Assent 1 Use the following information to answer question 7 National Election Results 2004 NUMBER PARTY % OF SEATS LIBERALS 135 36.7 % CONSERVATIVES 99 29.6 % BLOC QUEBECOIS 54 12.4 % NDP 19 15.7 % GREEN 0 4.3 % INDEPENDENT 1 0.5 % Seat Total: 308 100 % 7. -

Proquest Dissertations

OPPOSITION TO CONSCRIPTION IN ONTARIO 1917 A thesis submitted to the Department of History of the University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. % L,., A: 6- ''t, '-'rSily O* John R. Witham 1970 UMI Number: EC55241 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform EC55241 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE:IDEOLOGICAL OPPOSITION 8 CHAPTER TWO:THE TRADE UNIONS 33 CHAPTER THREE:THE FARMERS 63 CHAPTER FOUR:THE LIBERAL PARTI 93 CONCLUSION 127 APPENDIX A# Ontario Liberals Sitting in the House of Commons, May and December, 1917 • 131 APPENDIX B. "The Fiery Cross is now uplifted throughout Canada." 132 KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS 135 BIBLIOGRAPHY 136 11 INTRODUCTION The Introduction of conscription in 1917 evoked a deter mined, occasionally violent opposition from French Canadians. Their protests were so loud and so persistent that they have tended to obscure the fact that English Canada did not unanimous ly support compulsory military service. -

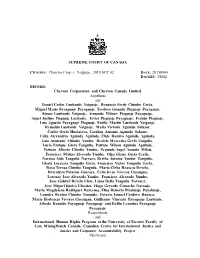

Supreme Court of Canada Judgment in Chevron Corp V Yaiguaje 2015

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA CITATION: Chevron Corp. v. Yaiguaje, 2015 SCC 42 DATE: 20150904 DOCKET: 35682 BETWEEN: Chevron Corporation and Chevron Canada Limited Appellants and Daniel Carlos Lusitande Yaiguaje, Benancio Fredy Chimbo Grefa, Miguel Mario Payaguaje Payaguaje, Teodoro Gonzalo Piaguaje Payaguaje, Simon Lusitande Yaiguaje, Armando Wilmer Piaguaje Payaguaje, Angel Justino Piaguaje Lucitante, Javier Piaguaje Payaguaje, Fermin Piaguaje, Luis Agustin Payaguaje Piaguaje, Emilio Martin Lusitande Yaiguaje, Reinaldo Lusitande Yaiguaje, Maria Victoria Aguinda Salazar, Carlos Grefa Huatatoca, Catalina Antonia Aguinda Salazar, Lidia Alexandria Aguinda Aguinda, Clide Ramiro Aguinda Aguinda, Luis Armando Chimbo Yumbo, Beatriz Mercedes Grefa Tanguila, Lucio Enrique Grefa Tanguila, Patricio Wilson Aguinda Aguinda, Patricio Alberto Chimbo Yumbo, Segundo Angel Amanta Milan, Francisco Matias Alvarado Yumbo, Olga Gloria Grefa Cerda, Narcisa Aida Tanguila Narvaez, Bertha Antonia Yumbo Tanguila, Gloria Lucrecia Tanguila Grefa, Francisco Victor Tanguila Grefa, Rosa Teresa Chimbo Tanguila, Maria Clelia Reascos Revelo, Heleodoro Pataron Guaraca, Celia Irene Viveros Cusangua, Lorenzo Jose Alvarado Yumbo, Francisco Alvarado Yumbo, Jose Gabriel Revelo Llore, Luisa Delia Tanguila Narvaez, Jose Miguel Ipiales Chicaiza, Hugo Gerardo Camacho Naranjo, Maria Magdalena Rodriguez Barcenes, Elias Roberto Piyahuaje Payahuaje, Lourdes Beatriz Chimbo Tanguila, Octavio Ismael Cordova Huanca, Maria Hortencia Viveros Cusangua, Guillermo Vincente Payaguaje Lusitante, Alfredo Donaldo Payaguaje Payaguaje and Delfin Leonidas Payaguaje Payaguaje Respondents - and - International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law, MiningWatch Canada, Canadian Centre for International Justice and Justice and Corporate Accountability Project Interveners CORAM: McLachlin C.J. and Abella, Rothstein, Cromwell, Karakatsanis, Wagner and Gascon JJ. REASONS FOR JUDGMENT: Gascon J. (McLachlin C.J. and Abella, Rothstein, (paras. 1 to 96) Cromwell, Karakatsanis and Wagner JJ. -

Brief by Professor François Larocque Research Chair In

BRIEF BY PROFESSOR FRANÇOIS LAROCQUE RESEARCH CHAIR IN LANGUAGE RIGHTS UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA PRESENTED TO THE SENATE STANDING COMMITTEE ON OFFICIAL LANGUAGES AS PART OF ITS STUDY OF THE OFFICIAL LANGUAGES REFORM PROPOSAL UNVEILED ON FEBRUARY 19, 2021, BY THE MINISTER OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND OFFICIAL LANGUAGES, ENGLISH AND FRENCH: TOWARDS A SUBSTANTIVE EQUALITY OF OFFICIAL LANGUAGES IN CANADA MAY 31, 2021 Professor François Larocque Faculty of Law, Common Law Section University of Ottawa 57 Louis Pasteur Ottawa, ON K1J 6N5 Telephone: 613-562-5800, ext. 3283 Email: [email protected] 1. Thank you very much to the honourable members of the Senate Standing Committee on Official Languages (the “Committee”) for inviting me to testify and submit a brief as part of the study of the official languages reform proposal entitled French and English: Towards a Substantive Equality of Official Languages in Canada (“the reform proposal”). A) The reform proposal includes ambitious and essential measures 2. First, I would like to congratulate the Minister of Economic Development and Official Languages for her leadership and vision. It is, in my opinion, the most ambitious official languages reform proposal since the enactment of the Constitution Act, 1982 (“CA1982”)1 and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (“Charter”),2 which enshrined the main provisions of the Official Languages Act (“OLA”)3 of 1969 in the Canadian Constitution. The last reform of the OLA was in 1988 and it is past time to modernize it to adapt it to Canada’s linguistic realities and challenges in the 21st century. 3. The Charter and the OLA proclaim that “English and French are the official languages of Canada and have equality of status and equal rights and privileges as to their use in all institutions of the Parliament and government of Canada.”4 In reality, however, as reported by Statistics Canada,5 English is dominant everywhere, while French is declining, including in Quebec. -

The Parliament

The Parliament is composed of 3 distinct elements,the Queen1 the Senate and the House of Representatives.2 These 3 elements together characterise the nation as being a constitutional monarchy, a parliamentary democracy and a federation. The Constitution vests in the Parliament the legislative power of the Common- wealth. The legislature is bicameral, which is the term commoniy used to indicate a Par- liament of 2 Houses. Although the Queen is nominally a constituent part of the Parliament the Consti- tution immediately provides that she appoint a Governor-General to be her representa- tive in the Commonwealth.3 The Queen's role is little more than titular as the legislative and executive powers and functions of the Head of State are vested in the Governor- General by virtue of the Constitution4, and by Letters Patent constituting the Office of Governor-General.5 However, while in Australia, the Sovereign has performed duties of the Governor-General in person6, and in the event of the Queen being present to open Parliament, references to the Governor-General in the relevant standing orders7 are to the extent necessary read as references to the Queen.s The Royal Style and Titles Act provides that the Queen shall be known in Australia and its Territories as: Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God Queen of Australia and Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth.* There have been 19 Governors-General of Australia10 since the establishment of the Commonwealth, 6 of whom (including the last 4) have been Australian born. The Letters Patent, of 29 October 1900, constituting the office of Governor- General, 'constitute, order, and declare that there shall be a Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief in and over' the Commonwealth. -

Canada-U.S. Relations

Canada-U.S. Relations Updated February 10, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov 96-397 SUMMARY 96-397 Canada-U.S. Relations February 10, 2021 The United States and Canada typically enjoy close relations. The two countries are bound together by a common 5,525-mile border—“the longest undefended border in the world”—as Peter J. Meyer well as by shared history and values. They have extensive trade and investment ties and long- Specialist in Latin standing mutual security commitments under NATO and North American Aerospace Defense American and Canadian Command (NORAD). Canada and the United States also cooperate closely on intelligence and Affairs law enforcement matters, placing a particular focus on border security and cybersecurity initiatives in recent years. Ian F. Fergusson Specialist in International Although Canada’s foreign and defense policies usually are aligned with those of the United Trade and Finance States, disagreements arise from time to time. Canada’s Liberal Party government, led by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, has prioritized multilateral efforts to renew and strengthen the rules- based international order since coming to power in November 2015. It expressed disappointment with former President Donald Trump’s decisions to withdraw from international organizations and accords, and it questioned whether the United States was abandoning its global leadership role. Cooperation on international issues may improve under President Joe Biden, who spoke with Prime Minister Trudeau in his first call to a foreign leader and expressed interest in working with Canada to address climate change and other global challenges. The United States and Canada have a deep economic partnership, with approximately $1.4 billion of goods crossing the border each day in 2020. -

Manitoba, Attorney General of New Brunswick, Attorney General of Québec

Court File No. 38663 and 38781 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (On Appeal from the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal) IN THE MATTER OF THE GREENHOUSE GAS POLLUTION ACT, Bill C-74, Part V AND IN THE MATTER OF A REFERENCE BY THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL TO THE COURT OF APPEAL UNDER THE CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS ACT, 2012, SS 2012, c C-29.01 BETWEEN: ATTORNEY GENERAL OF SASKATCHEWAN APPELLANT -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA RESPONDENT -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ALBERTA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF QUÉBEC INTERVENERS (Title of Proceeding continued on next page) FACTUM OF THE INTERVENER, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MANITOBA GOWLING WLG (CANADA) LLP Legal Services Branch, Constitutional Law Section Barristers & Solicitors 1230 - 405 Broadway Suite 2600, 160 Elgin Street Winnipeg MB R3C 3L6 Ottawa ON K1P 1C3 Michael Conner / Allison Kindle Pejovic D. Lynne Watt Tel: (204) 391-0767/(204) 945-2856 Tel: (613) 786-8695 Fax: (204) 945-0053 Fax: (613) 788-3509 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for the Intervener Ottawa Agent for the Intervener -and - SASKATCHEWAN POWER CORPORATION AND SASKENERGY INCORPORATED, CANADIAN TAXPAYERS FEDERATION, UNITED CONSERVATIVE ASSOCIATION, AGRICULTURAL PRODUCERS ASSOCIATION OF SASKATCHEWAN INC., INTERNATIONAL EMISSIONS TRADING ASSOCIATION, CANADIAN PUBLIC HEALTH -

Youth Activity Book (PDF)

Supreme Court of Canada Youth Activity Book Photos Philippe Landreville, photographer Library and Archives Canada JU5-24/2016E-PDF 978-0-660-06964-7 Supreme Court of Canada, 2019 Hello! My name is Amicus. Welcome to the Supreme Court of Canada. I will be guiding you through this activity book, which is a fun-filled way for you to learn about the role of the Supreme Court of Canada in the Canadian judicial system. I am very proud to have been chosen to represent the highest court in the country. The owl is a good ambassador for the Supreme Court because it symbolizes wisdom and learning and because it is an animal that lives in Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada stands at the top of the Canadian judicial system and is therefore Canada’s highest court. This means that its decisions are final. The cases heard by the Supreme Court of Canada are those that raise questions of public importance or important questions of law. It is time for you to test your knowledge while learning some very cool facts about Canada’s highest court. 1 Colour the official crest of the Supreme Court of Canada! The crest of the Supreme Court is inlaid in the centre of the marble floor of the Grand Entrance Hall. It consists of the letters S and C encircled by a garland of leaves and was designed by Ernest Cormier, the building’s architect. 2 Let’s play detective: Find the words and use the remaining letters to find a hidden phrase. The crest of the Supreme Court is inlaid in the centre of the marble floor of the Grand Entrance Hall. -

Legislative Chambers: Unicameral Or Bicameral?

Legislative Chambers: Unicameral or Bicameral? Legislative Chambers: Unicameral or Bicameral? How many chambers a parliament should have is a controversial question in constitutional law. Having two legislative chambers grew out of the monarchy system in the UK and other European countries, where there was a need to represent both the aristocracy and the common man, and out of the federal system in the US. where individual states required representation. In recent years, unicameral systems, or those with one legislative chamber, were associated with authoritarian states. Although that perception does not currently hold true, there appears to be a general trend toward two chambers in emerging democracies, particularly in larger countries. Given historical, cultural and political factors, governments must decide whether one-chamber or two chambers better serve the needs of the country. Bicameral Chambers A bicameral legislature is composed of two-chambers, usually termed the lower house and upper house. The lower house is usually based proportionally on population with each member representing the same number of citizens in each district or region. The upper house varies more broadly in the way in which members are selected, including inheritance, appointment by various bodies and direct and indirect elections. Representation in the upper house can reflect political subdivisions, as is the case for the US Senate, German Bundesrat and Indian Rajya Sabha. Bicameral systems tend to occur in federal states, because of that system’s two-tiered power structure. Where subdivisions are drawn to coincide with other important societal units, the upper house can serve to represent ethnic, religious or tribal groupings, as in India or Ethiopia. -

Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-Study*

brazilianpoliticalsciencereview ARTICLE Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-study* Marta Arretche University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil The article distinguishes federal states from bicameralism and mechanisms of territorial representation in order to examine the association of each with institutional change in 32 countries by using constitutional amendments as a proxy. It reveals that bicameralism tends to be a better predictor of constitutional stability than federalism. All of the bicameral cases that are associated with high rates of constitutional amendment are also federal states, including Brazil, India, Austria, and Malaysia. In order to explore the mechanisms explaining this unexpected outcome, the article also examines the voting behavior of Brazilian senators constitutional amendments proposals (CAPs). It shows that the Brazilian Senate is a partisan Chamber. The article concludes that regional influence over institutional change can be substantially reduced, even under symmetrical bicameralism in which the Senate acts as a second veto arena, when party discipline prevails over the cohesion of regional representation. Keywords: Federalism; Bicameralism; Senate; Institutional change; Brazil. well-established proposition in the institutional literature argues that federal Astates tend to take a slow reform path. Among other typical federal institutions, the second legislative body (the Senate) common to federal systems (Lijphart 1999; Stepan * The Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado -

CANADIAN POLITICS Contents

McMaster University, Department of Political Science, POLSCI 4O06/6O06 CANADIAN POLITICS Fall/Winter 2018-19 Instructor: Dr. Geoffrey Cameron Office: KTH 505 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Friday, 12pm – 2pm Seminar: Friday, 8:30am – 11:20am Room: KTH 105 Contents Course Description .......................................................................................................... 3 Course Objectives ........................................................................................................... 3 Required Materials and Texts ......................................................................................... 3 Course Evaluation – Overview ........................................................................................ 3 Course Evaluation – Details ............................................................................................ 3 Attendance (10%) ........................................................................................................ 3 Participation (10%) ...................................................................................................... 4 Class Presentation (5%) .............................................................................................. 4 In-Class Test (10%), September 28............................................................................. 4 Research Proposal (15%), due February 8 ................................................................. 4 Research Proposal Presentation (5%) ........................................................................ -

Celebrating the Right Brain Snail-Mail Gossip • a 21St-Century Safari • the Donors’ Report

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2009 celebrating the right brain snail-mail gossip • a 21st-century safari • the donors’ report revTrinity_fall'09.indd 1 10/6/09 5:11:45 PM provost’smessage Learned and Beautiful Trinity has always been about more than setting and surpassing academic expectations The start of the school year is always exciting and exhausting: ecstasy that accompany academic endeavour, and the final line new faces appear, old faces reappear, and the College looks its of the College song celebrates the attainments of the women of best after a summer of repair and refurbishment. The new back St. Hilda’s as doctae atque bellae (learned and beautiful). Both field is a wonderful new asset that I hope will be heavily used, and make it clear that here, scholarship alone is not enough. the quad, now wireless, has in recent weeks seen students loung- Even if our Aberdeen-born founder seems suitably stern ing and labouring. The official opening of the green roof on in his portraits, John Strachan was not immune to relaxation. Cartwright Hall, largely funded by the generosity of the Scotch blood, after all, flowed in his veins, sometimes in ap- class of ’58, takes place this month, and the re-roofing of the parently undiluted quantities. At one point, the Bishop, having Larkin Building to accommodate solar panels, primarily been told that one of his clergy was too fond of the bottle, is funded by students, is well underway. Frosh week was by all said to have replied: “Tut, tut: That is a most extravagant way accounts a great success, and at Matriculation we welcomed to buy whisky; I always buy mine by the barrel.” (Presumably the incoming class of ’13, and honoured three of our own: the same barrel he appears to be wearing in the painting that Donald Macdonald, Margaret MacMillan, and Richard Alway.