Von Neumann's Impossibility Proof: Mathematics in the Service Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Degruyter Opphil Opphil-2020-0010 147..160 ++

Open Philosophy 2020; 3: 147–160 Object Oriented Ontology and Its Critics Simon Weir* Living and Nonliving Occasionalism https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2020-0010 received November 05, 2019; accepted February 14, 2020 Abstract: Graham Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology has employed a variant of occasionalist causation since 2002, with sensual objects acting as the mediators of causation between real objects. While the mechanism for living beings creating sensual objects is clear, how nonliving objects generate sensual objects is not. This essay sets out an interpretation of occasionalism where the mediating agency of nonliving contact is the virtual particles of nominally empty space. Since living, conscious, real objects need to hold sensual objects as sub-components, but nonliving objects do not, this leads to an explanation of why consciousness, in Object-Oriented Ontology, might be described as doubly withdrawn: a sensual sub-component of a withdrawn real object. Keywords: Graham Harman, ontology, objects, Timothy Morton, vicarious, screening, virtual particle, consciousness 1 Introduction When approaching Graham Harman’s fourfold ontology, it is relatively easy to understand the first steps if you begin from an anthropocentric position of naive realism: there are real objects that have their real qualities. Then apart from real objects are the objects of our perception, which Harman calls sensual objects, which are reduced distortions or caricatures of the real objects we perceive; and these sensual objects have their own sensual qualities. It is common sense that when we perceive a steaming espresso, for example, that we, as the perceivers, create the image of that espresso in our minds – this image being what Harman calls a sensual object – and that we supply the energy to produce this sensual object. -

6. Knowledge, Information, and Entropy the Book John Von

6. Knowledge, Information, and Entropy The book John von Neumann and the Foundations of Quantum Physics contains a fascinating and informative article written by Eckehart Kohler entitled “Why von Neumann Rejected Carnap’s Dualism of Information Concept.” The topic is precisely the core issue before us: How is knowledge connected to physics? Kohler illuminates von Neumann’s views on this subject by contrasting them to those of Carnap. Rudolph Carnap was a distinguished philosopher, and member of the Vienna Circle. He was in some sense a dualist. He had studied one of the central problems of philosophy, namely the distinction between analytic statements and synthetic statements. (The former are true or false by virtue of a specified set of rules held in our minds, whereas the latter are true or false by virtue their concordance with physical or empirical facts.) His conclusions had led him to the idea that there are two different domains of truth, one pertaining to logic and mathematics and the other to physics and the natural sciences. This led to the claim that there are “Two Concepts of Probability,” one logical the other physical. That conclusion was in line with the fact that philosophers were then divided between two main schools as to whether probability should be understood in terms of abstract idealizations or physical sequences of outcomes of measurements. Carnap’s bifurcations implied a similar division between two different concepts of information, and of entropy. In 1952 Carnap was working at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and about to publish a work on his dualistic theory of information, according to which epistemological concepts like information should be treated separately from physics. -

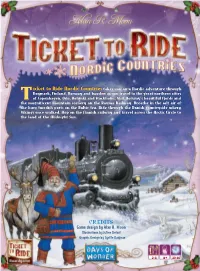

Rules EN 2015 TTR2 Rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2

[T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2 icket to Ride Nordic Countries takes you on a Nordic adventure through Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden as you travel to the great northern cities T of Copenhagen, Oslo, Helsinki and Stockholm. Visit Norway's beautiful fjords and the magnificent mountain scenery on the Rauma Railway. Breathe in the salt air of the busy Swedish ports on the Baltic Sea. Ride through the Danish countryside where Vikings once walked. Hop-on the Finnish railway and travel across the Arctic Circle to the land of the Midnight Sun. CREDITS Game design by Alan R. Moon Illustrations by Julien Delval Graphic Design by Cyrille Daujean 2-3 8+ 30-60’ [T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:52 Page3 Components 1 Globetrotter Bonus card u 1 Board map of Scandinavian train routes for the most completed tickets u 120 Colored Train cars (40 each in 3 different colors, plus a few spare) 46 Destination u 157 Illustrated cards: Ticket cards 110 Train cards : 12 of each color, plus 14 Locomotives ∫ ∂ u 3 Wooden Scoring Markers (1 for each player matching the train colors) u 1 Rules booklet Setting up the Game Place the board map in the center of the table. Each player takes a set of 40 Colored Train Cars along with its matching Scoring Marker. Each player places his Scoring Marker on the starting π location next to the 100 number ∂ on the Scoring Track running along the map's border. Throughout the game, each time a player scores points, he will advance his marker accordingly. -

Are Information, Cognition and the Principle of Existence Intrinsically

Adv. Studies Theor. Phys., Vol. 7, 2013, no. 17, 797 - 818 HIKARI Ltd, www.m-hikari.com http://dx.doi.org/10.12988/astp.2013.3318 Are Information, Cognition and the Principle of Existence Intrinsically Structured in the Quantum Model of Reality? Elio Conte(1,2) and Orlando Todarello(2) (1)School of International Advanced Studies on Applied Theoretical and non Linear Methodologies of Physics, Bari, Italy (2)Department of Neurosciences and Sense Organs University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Bari, Italy Copyright © 2013 Elio Conte and Orlando Todarello. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract The thesis of this paper is that Information, Cognition and a Principle of Existence are intrinsically structured in the quantum model of reality. We reach such evidence by using the Clifford algebra. We analyze quantization in some traditional cases of quantum mechanics and, in particular in quantum harmonic oscillator, orbital angular momentum and hydrogen atom. Keywords: information, quantum cognition, principle of existence, quantum mechanics, quantization, Clifford algebra. Corresponding author: [email protected] Introduction The earliest versions of quantum mechanics were formulated in the first decade of the 20th century following about the same time the basic discoveries of physics as 798 Elio Conte and Orlando Todarello the atomic theory and the corpuscular theory of light that was basically updated by Einstein. Early quantum theory was significantly reformulated in the mid- 1920s by Werner Heisenberg, Max Born and Pascual Jordan, who created matrix mechanics, Louis de Broglie and Erwin Schrodinger who introduced wave mechanics, and Wolfgang Pauli and Satyendra Nath Bose who introduced the statistics of subatomic particles. -

A Simple Proof That the Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics Is Inconsistent

A simple proof that the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is inconsistent Shan Gao Research Center for Philosophy of Science and Technology, Shanxi University, Taiyuan 030006, P. R. China E-mail: [email protected]. December 25, 2018 Abstract The many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is based on three key assumptions: (1) the completeness of the physical description by means of the wave function, (2) the linearity of the dynamics for the wave function, and (3) multiplicity. In this paper, I argue that the combination of these assumptions may lead to a contradiction. In order to avoid the contradiction, we must drop one of these key assumptions. The many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics (MWI) assumes that the wave function of a physical system is a complete description of the system, and the wave function always evolves in accord with the linear Schr¨odingerequation. In order to solve the measurement problem, MWI further assumes that after a measurement with many possible results there appear many equally real worlds, in each of which there is a measuring device which obtains a definite result (Everett, 1957; DeWitt and Graham, 1973; Barrett, 1999; Wallace, 2012; Vaidman, 2014). In this paper, I will argue that MWI may give contradictory predictions for certain unitary time evolution. Consider a simple measurement situation, in which a measuring device M interacts with a measured system S. When the state of S is j0iS, the state of M does not change after the interaction: j0iS jreadyiM ! j0iS jreadyiM : (1) When the state of S is j1iS, the state of M changes and it obtains a mea- surement result: j1iS jreadyiM ! j1iS j1iM : (2) 1 The interaction can be represented by a unitary time evolution operator, U. -

Detailing Coherent, Minimum Uncertainty States of Gravitons, As

Journal of Modern Physics, 2011, 2, 730-751 doi:10.4236/jmp.2011.27086 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jmp) Detailing Coherent, Minimum Uncertainty States of Gravitons, as Semi Classical Components of Gravity Waves, and How Squeezed States Affect Upper Limits to Graviton Mass Andrew Beckwith1 Department of Physics, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China E-mail: [email protected] Received April 12, 2011; revised June 1, 2011; accepted June 13, 2011 Abstract We present what is relevant to squeezed states of initial space time and how that affects both the composition of relic GW, and also gravitons. A side issue to consider is if gravitons can be configured as semi classical “particles”, which is akin to the Pilot model of Quantum Mechanics as embedded in a larger non linear “de- terministic” background. Keywords: Squeezed State, Graviton, GW, Pilot Model 1. Introduction condensed matter application. The string theory metho- dology is merely extending much the same thinking up to Gravitons may be de composed via an instanton-anti higher than four dimensional situations. instanton structure. i.e. that the structure of SO(4) gauge 1) Modeling of entropy, generally, as kink-anti-kinks theory is initially broken due to the introduction of pairs with N the number of the kink-anti-kink pairs. vacuum energy [1], so after a second-order phase tran- This number, N is, initially in tandem with entropy sition, the instanton-anti-instanton structure of relic production, as will be explained later, gravitons is reconstituted. This will be crucial to link 2) The tie in with entropy and gravitons is this: the two graviton production with entropy, provided we have structures are related to each other in terms of kinks and sufficiently HFGW at the origin of the big bang. -

Performing History Studies in Theatre History & Culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY

Performing history studies in theatre history & culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY theatrical representations of the past in contemporary theatre Freddie Rokem University of Iowa Press Iowa City University of Iowa Press, Library of Congress Iowa City 52242 Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2000 by the Rokem, Freddie, 1945– University of Iowa Press Performing history: theatrical All rights reserved representations of the past in Printed in the contemporary theatre / by Freddie United States of America Rokem. Design by Richard Hendel p. cm.—(Studies in theatre http://www.uiowa.edu/~uipress history and culture) No part of this book may be repro- Includes bibliographical references duced or used in any form or by any and index. means, without permission in writing isbn 0-87745-737-5 (cloth) from the publisher. All reasonable steps 1. Historical drama—20th have been taken to contact copyright century—History and criticism. holders of material used in this book. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), The publisher would be pleased to make in literature. 3. France—His- suitable arrangements with any whom tory—Revolution, 1789–1799— it has not been possible to reach. Literature and the revolution. I. Title. II. Series. The publication of this book was generously supported by the pn1879.h65r65 2000 University of Iowa Foundation. 809.2Ј9358—dc21 00-039248 Printed on acid-free paper 00 01 02 03 04 c 54321 for naama & ariel, and in memory of amitai contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 1 Refractions of the Shoah on Israeli Stages: -

NEW Media Document.Indd

MEDIA RELEASE WICKED is coming to Australia. The hottest musical in the world will open in Melbourne’s Regent Theatre in July 2008. With combined box office sales of $US 1/2 billion, WICKED is already one of the most successful shows in theatre history. WICKED opened on Broadway in October 2003. Since then over two and a half million people have seen WICKED in New York and just over another two million have seen the North American touring production. The smash-hit musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz (Godspell, Pippin, Academy Award-winner for Pocahontas and The Prince of Egypt) and book by Winnie Holzman (My So Called Life, Once And Again and thirtysomething) is based on the best-selling novel by Gregory Maguire. WICKED is produced by Marc Platt, Universal Pictures, The Araca Group, Jon B. Platt and David Stone. ‘We’re delighted that Melbourne is now set to follow WICKED productions in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, the North American tour and London’s West End,’ Marc Platt and David Stone said in a joint statement from New York. ‘Melbourne will join new productions springing up around the world over the next 16 months, and we’re absolutely sure that Aussies – and international visitors to Melbourne – will be just as enchanted by WICKED as the audiences are in America and England.’ WICKED will premiere in Tokyo in June; Stuttgart in November; Melbourne in July 2008; and Amsterdam in 2008. Winner of 15 major awards including the Grammy Award and three Tony Awards, WICKED is the untold story of the witches of Oz. -

Download Download

ISSN 2002-3898 © Ken Nielsen and Nordic Theatre Studies DOI: https://doi.org/10.7146/nts.v25i1.110898 Published with support from Nordic Board for Periodicals in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NOP-HS) Gone With the Plague: Negotiating Sexual Citizenship in Crisis Ken Nielsen ABSTRACT This article suggests that two historical performances by the Danish subcultural theatre group Buddha og Bag- bordsindianerne should be understood not simply as underground, amateur cabarets, but rather that they should be theorized as creating a critical temporality, as theorized by David Román. As such, they function to complicate the past and the present in rejecting a discourse of decency and embracing a queerer, more radical sense of citizenship. In other words, conceptualizing these performances as critical temporalities allows us not only to understand two particular theatrical performances of gay male identity and AIDS in Copenhagen in the late 1980s, but also to theorize more deeply embedded tensions between queer identities, temporality, and citizenship. Furthermore, by reading these performances and other performances like them as critical temporalities we reject the willful blindness of traditional theatre histories and make a more radical theatre history possible. Keywords: BIOGRAPHY Ken Nielsen is a Postdoctoral lecturer in the Princeton Writing Program, Princeton University, where he is currently teaching classes ranging from contemporary confession culture to tragedy. He holds a PhD in the- atre studies from The Graduate Center, City University of New York, with an emphasis on Gay and Lesbian Studies from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS). In addition, he holds an MA in Theatre Research from the University of Copenhagen. -

Abstract for Non Ideal Measurements by David Albert (Philosophy, Columbia) and Barry Loewer (Philosophy, Rutgers)

Abstract for Non Ideal Measurements by David Albert (Philosophy, Columbia) and Barry Loewer (Philosophy, Rutgers) We have previously objected to "modal interpretations" of quantum theory by showing that these interpretations do not solve the measurement problem since they do not assign outcomes to non_ideal measurements. Bub and Healey replied to our objection by offering alternative accounts of non_ideal measurements. In this paper we argue first, that our account of non_ideal measurements is correct and second, that even if it is not it is very likely that interactions which we called non_ideal measurements actually occur and that such interactions possess outcomes. A defense of of the modal interpretation would either have to assign outcomes to these interactions, show that they don't have outcomes, or show that in fact they do not occur in nature. Bub and Healey show none of these. Key words: Foundations of Quantum Theory, The Measurement Problem, The Modal Interpretation, Non_ideal measurements. Non_Ideal Measurements Some time ago, we raised a number of rather serious objections to certain so_called "modal" interpretations of quantum theory (Albert and Loewer, 1990, 1991).1 Andrew Elby (1993) recently developed one of these objections (and added some of his own), and Richard Healey (1993) and Jeffrey Bub (1993) have recently published responses to us and Elby. It is the purpose of this note to explain why we think that their responses miss the point of our original objection. Since Elby's, Bub's, and Healey's papers contain excellent descriptions both of modal theories and of our objection to them, only the briefest review of these matters will be necessary here. -

Grete Hermann on Von Neumann's No-Hidden-Variables Proof

Challenging the gospel: Grete Hermann on von Neumann’s no-hidden-variables proof M.P Seevinck ∞ ∞ Radboud University University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands May 2012 1 Preliminary ∞ ∞ In 1932 John von Neumann had published in his celebrated book on the Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik, a proof of the impossibility of theories which, by using the so- called hidden variables, attempt to give a deterministic explana- tion of quantum mechanical behaviors. ◮ Von Neumann’s proof was sort of holy: ‘The truth, however, happens to be that for decades nobody spoke up against von Neumann’s arguments, and that his con- clusions were quoted by some as the gospel.’ (F. J. Belinfante, 1973) 2 ◮ In 1935 Grete Hermann challenged this gospel by criticizing the von Neumann proof on a fundamental point. This was however not widely known and her criticism had no impact whatsoever. ◮ 30 years later John Bell gave a similar critique, that did have great foundational impact. 3 Outline ∞ ∞ 1. Von Neumann’s 1932 no hidden variable proof 2. The reception of this proof + John Bell’s 1966 criticism 3. Grete Hermann’s critique (1935) on von Neu- mann’s argument 4. Comparison to Bell’s criticism 5. The reception of Hermann’s criticism 4 Von Neumann’s 1932 no hidden variable argument ∞ ∞ Von Neumann: What reasons can be given for the dispersion found in some quantum ensembles? (Case I): The individual systems differ in additional parameters, which are not known to us, whose values de- termine precise outcomes of measurements. = deterministic hidden variables ⇒ (Case II): ‘All individual systems are in the same state, but the laws of nature are not causal’. -

Neuer Nachrichtenbrief Der Gesellschaft Für Exilforschung E. V

Neuer Nachrichtenbrief der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e. V. Nr. 53 ISSN 0946-1957 Juli 2019 Inhalt In eigener Sache In eigener Sache 1 Bericht Jahrestagung 2019 1 Später als gewohnt erscheint dieses Jahr der Doktoranden-Workshop 2019 6 Sommer-Nachrichtenbrief. Grund ist die Protokoll Mitgliederversammlung 8 diesjährige Jahrestagung, die im Juni AG Frauen im Exil 14 stattfand. Der Tagungsbericht und das Ehrenmitgliedschaft Judith Kerr 15 Protokoll der Mitgliederversammlung Laudatio 17 sollten aber in dieser Ausgabe erscheinen. Erinnerungen an Kurt Harald Der Tagungsbericht ist wiederum ein Isenstein 20 Gemeinschaftsprojekt, an dem sich diesmal Untersuchung Castrum Peregrini 21 nicht nur „altgediente“ GfE-Mitglieder Projekt „Gerettet“ 22 beteiligten, sondern dankenswerterweise CfP AG Frauen im Exil 24 auch zwei Doktorandinnen der Viadrina. CfP Society for Exile Studies 25 Ich hoffe, für alle, die nicht bei der Tagung Suchanzeigen 27 sein konnten, bieten Bericht und Protokoll Leserbriefe 27 genügend Informationen. Impressum 27 Katja B. Zaich Aus der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung Exil(e) und Widerstand Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung in Frankfurt an der Oder vom 20.-22. Juni 2019 Die Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft fand in diesem Jahr an einem sehr würdigen und dem Geiste der Veranstaltung kongenialen Ort statt, waren doch die Erbauer des Logenhauses in Frankfurt an der Oder die Mitglieder der 1776 gegründeten Freimaurerloge „Zum aufrichtigen Herzen“, die 1935 unter dem Zwang der Nazi-Diktatur ihre Tätigkeit einstellen musste und diese erst 1992 wieder aufnehmen konnte. Im Festsaal des Logenhauses versammelten sich am Donnerstagnachmittag Exilforscher/innen, Studierende und Gäste aus verschiedenen Ländern, darunter etwa 30 Mitglieder der Gesellschaft. Auf die Frage „Was ist die Freimaurerei?“ findet sich auf der Homepage der heute wieder dort arbeitenden Loge eine alte englische Definition, in der es unter anderem heißt: „gegen das Unrecht ist sie Widerstand“.