Chapter Thirty Three Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birdsong in the Music of Olivier Messiaen a Thesis Submitted To

P Birdsongin the Music of Olivier Messiaen A thesissubmitted to MiddlesexUniversity in partial fulfilment of the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy David Kraft School of Art, Design and Performing Arts Nfiddlesex University December2000 Abstract 7be intentionof this investigationis to formulatea chronologicalsurvey of Messiaen'streatment of birdsong,taking into accountthe speciesinvolved and the composer'sevolving methods of motivic manipulation,instrumentation, incorporation of intrinsic characteristicsand structure.The approachtaken in this studyis to surveyselected works in turn, developingappropriate tabular formswith regardto Messiaen'suse of 'style oiseau',identified bird vocalisationsand eventhe frequentappearances of musicthat includesfamiliar characteristicsof bird style, althoughnot so labelledin the score.Due to the repetitivenature of so manymotivic fragmentsin birdsong,it has becomenecessary to developnew terminology and incorporatederivations from other research findings.7be 'motivic classification'tables, for instance,present the essentialmotivic featuresin somevery complexbirdsong. The studybegins by establishingthe importanceof the uniquemusical procedures developed by Messiaen:these involve, for example,questions of form, melodyand rhythm.7he problemof is 'authenticity' - that is, the degreeof accuracywith which Messiaenchooses to treat birdsong- then examined.A chronologicalsurvey of Messiaen'suse of birdsongin selectedmajor works follows, demonstratingan evolutionfrom the ge-eralterm 'oiseau' to the preciseattribution -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Bmus 1 Analysis Week 9 Project 2

BMus 1 Analysis: Week 9 1 BMus 1 Analysis Week 9 Project 2 Just to remind you: the second project for this module is an essay (c. 1500 words) on one short post-tonal work from the list below. All of the works can be found in the library; if they’re not available for any reason, ask me for a copy. (Most can be found online as well.) Béla Bartók, 44 Duos for Violin, no. 33: ‘Erntelied’ (‘Harvest Song’) Harrison Birtwistle, Duets for Storab, any two movements Ruth Crawford-Seeger, String Quartet, movt. 2: ‘Leggiero’ or movt. 3: ‘Andante’ György Kurtag, Játékok Book 6, ‘In memoriam András Mihály’ Elisabeth Lutyens, Présages op. 53, theme and variations 1-2. Olivier Messiaen, Préludes, no. 1: ’La Colombe’ Kaija Saariaho, Sept Papillons, movements 1 and 2 Arnold Schoenberg, 6 Little Piano Pieces, Op.19: No. 2 (Langsam) Igor Stravinsky, 3 pieces for String Quartet, no. 1 Anton Webern, Variations op 27: no. 2 What to cover You may format your essay as you wish, according to what best suits the piece you’ve selected. However, you should aim to comment on the following (interrelated) features of your chosen work: • Formal Design o How is this articulated? This may involve pitch / tempo / changes of texture / dynamics / phrasing and other musical features. • Pitch Structure o Use of interval / mode(s) / pitch sets / 12-note chords and other techniques • Nature and Handling of Melodic and Harmonic Materials o How is the material constructed, treated, developed and/or elaboration in the work? Do not forget the importance of rhythm as well as pitch. -

PROGRAM C'd I .:R:F 1=Jj 5D3

PROGRAM C'D I .:r:F 1=Jj 5D3 Piece pour piano et quatuor acordes (1991) ...........':!:!..?:..?::........... Olivier Messiaen (1908·1992) Luke Fitzpatrick, violin Hye Jung Yang, cello Allion Salvador, violin Zack Myers, piano Vijay Chalasani, viola z.. Feuilles atravers les cloches (1998) .................?.~......:c............................ Tristan Murall (b. 1947) Natalie Ham, flute Isabella Kodama, cello Luke Fitzpatrick, violin Steven Damouni, piano 3 Rain Spell (1983) ................................9..;.H.:t..................................... Toru Takemitsu (1930·1996) Natalie Ham, flute Lauren Wessels, harp Ivan Arteaga, clarinet Ania Stachurska, piano Isaac Anderson, vibraphone 4 Les Sept crimes de I'amour (1979) ................. J.?::.: ..f:?..r?.. ................... Georges Aperghis (b. 1945) Sequence I Sequence II Sequence III Sequence IV Sequence V Sequence VI Sequence VII Emerald Lessley, soprano Ivan Arteaga, clarinet Isaac Anderson, percussion INTERMISSION CD2-#l7-1 S'D'1 Quasi Hoquetus (1985) ................./.7:..=..1.........................................Sofia Gubaidulina (b. 1931) Luke fitzpatrick, viola Jamael Smith, bassoon Steven Damouni, piano String Quartet (1964) ........................~.?:.~ ..?:.? ........................Witold Lutoslawski (1913-1994) Introductory Movement Main Movement Luke Fitzpatrick, violin Vijay Chalasani, viola Allion Salvador, violin Hye Jung Yang, cello Program Notes by Luke Fitzpatrick Except Where Noted Piece pour pianoet quatuor acordes(1991) by Olivier Messiaen is one' -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

Activity Sheet

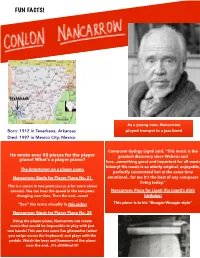

FUN FACTS! As a young man, Nancarrow Born: 1912 in Texarkana, Arkansas played trumpet in a jazz band Died: 1997 in Mexico City, Mexico Composer György Ligeti said, “This music is the He wrote over 50 pieces for the player greatest discovery since Webern and piano! What’s a player piano? Ives...something great and important for all music history! His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, The Entertainer on a player piano perfectly constructed but at the same time Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 21 emotional...for me it’s the best of any composer living today.” This is a canon in two parts (see p. 6 for more about canons). You can hear the speed in the two parts Nancarrow: Piece for Ligeti (for Ligeti’s 65th changing over time. Then the end...wow! birthday) “See” the score visually in this video This piece is in his “Boogie-Woogie style” Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 25 Using the player piano, Nancarrow can create music that would be impossible to play with just two hands! This one has some fun glissandos (when you swipe across the keyboard) and plays with the pedals. Watch the keys and hammers of the piano near the end...it’s aliiiiiiive!!!!! 1 FUN FACTS! Population: 130 million Capital: Mexico City (Pop: 9 million) Languages: Spanish and over 60 indigenous languages Currency: Peso Highest Peak: Pico de Orizaba volcano, 18,491 ft Flag: Legend says that the Aztecs settled and built their capital city (Tenochtitlan, Mexico City today) on the spot where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus, eating a snake. -

Preview Notes

PREVIEW NOTES Bella Hristova, violin and Amy Yang, piano Friday, January 31 – 8:00 PM American Philosophical Society, 427 Chestnut Street Program Violin Sonata No. 5 in F Major, “Spring” Louange à L’immortalité de Jésus Ludwig van Beethoven Olivier Messiaen Born: December 16, 1770 in Bonn, Germany Born: December 10, 1908 in Avignon, France Died: March 26, 1827 in Vienna, Austria Died: April 27, 1992 in Clichy, France Composed: 1800‐01 Composed: 1940‐41 Last PCMS performance: Elizabeth Pitcairn, 2010 Last PCMS performance: Musicians from Marlboro I, Duration: 24 minutes 2009 Duration: 11 minutes Beethoven’s fifth violin sonata was the first of his to break away from the Classical three‐movement sonata From one of the most significant and famous chamber format. It is a tentative breach, as the new scherzo compositions of the twentieth century, Louange à movement is just over a minute in length. The work’s I’lmmortalité de Jésus is the fifth movement of the final movement begins in a pleasant, rather courtly Quatour pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Mozartean style. This refrain returns in various guises, Time). Messiaen, a devout Catholic, drew his title and though never significantly altered; in between are minor musical imagery from Revelations 10:1‐7, concerning mode passages of some agitation and modest drama, the Angel that announces the end of time. Written while although the sunny disposition of the main theme wins Messiaen was being held as a prisoner of war, Eulogy to out in the end. the Immortality of Jesus represents Christ’s ascension into Heaven. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL How to cite: ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL (2021) English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13924/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush’s ‘Workers’ Music’ on 20 th Century Britain’s Left-Wing Music Scene Alice Robinson Abstract Workers’ music: songs to fight injustice, inequality and establish the rights of the working classes. This was a new, radical genre of music which communist composer, Alan Bush, envisioned in 1930s Britain. -

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, and PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice

Blurring the Border: Copland, Chávez, and Pan-Americanism Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Sierra, Candice Priscilla Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 23:10:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634377 BLURRING THE BORDER: COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, AND PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice Priscilla Sierra ________________________________ Copyright © Candice Priscilla Sierra 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples ……...……………………………………………………………… 4 Abstract………………...……………………………………………………………….……... 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter 1: Setting the Stage: Similarities in Upbringing and Early Education……………… 11 Chapter 2: Pan-American Identity and the Departure From European Traditions…………... 22 Chapter 3: A Populist Approach to Politics, Music, and the Working Class……………....… 39 Chapter 4: Latin American Impressions: Folk Song, Mexicanidad, and Copland’s New Career Paths………………………………………………………….…. 53 Chapter 5: Musical Aesthetics and Comparisons…………………………………………...... 64 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………. 82 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….. 85 4 LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES Example 1. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r17-1 to r18+3……………………………... 69 Example 2. Copland, Three Latin American Sketches: No. 3, Danza de Jalisco (1959–1972), r180+4 to r180+8……………………………………………………………………...... 70 Example 3. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r79-2 to r80+1…………………………….. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

The Function of Music in Sound Film

THE FUNCTION OF MUSIC IN SOUND FILM By MARIAN HANNAH WINTER o MANY the most interesting domain of functional music is the sound film, yet the literature on it includes only one major work—Kurt London's "Film Music" (1936), a general history that contains much useful information, but unfortunately omits vital material on French and German avant-garde film music as well as on film music of the Russians and Americans. Carlos Chavez provides a stimulating forecast of sound-film possibilities in "Toward a New Music" (1937). Two short chapters by V. I. Pudovkin in his "Film Technique" (1933) are brilliant theoretical treatises by one of the foremost figures in cinema. There is an ex- tensive periodical literature, ranging from considered expositions of the composer's function in film production to brief cultist mani- festos. Early movies were essentially action in a simplified, super- heroic style. For these films an emotional index of familiar music was compiled by the lone pianist who was musical director and performer. As motion-picture output expanded, demands on the pianist became more complex; a logical development was the com- pilation of musical themes for love, grief, hate, pursuit, and other cinematic fundamentals, in a volume from which the pianist might assemble any accompaniment, supplying a few modulations for transition from one theme to another. Most notable of the collec- tions was the Kinotek of Giuseppe Becce: A standard work of the kind in the United States was Erno Rapee's "Motion Picture Moods". During the early years of motion pictures in America few original film scores were composed: D.