Download .Pdf File of Volume 36

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

Booklist 3-4.Xlsx

2019 Years 3-4 Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Abela, Deborah The Stupendously Spectacular Spelling Bee 9781925324822 3-4, 5-6 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Agard, John Hello New! 978-1-84121-621-8 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan Please Mrs Butler 9780140314946 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan The Bravest Ever Bear 9780744578645 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan; Ingham, Bruce The Pencil 9781406309621 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan; Ingman, Bruce Previously 9781844280629 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan; Ingman, Bruce (ill.) Everybody Was a Baby Once 9781406321562 EC-2, 3-4 Airey, Miriam No Hat Brigade 978-1-74051-773-7 3-4 Alderson, Maggie Evangeline 9780670075355 EC-2, 3-4 Alexander, Goldie The Youngest Cameleer 978-1-74130-495-4 3-4, 5-6 Alexander, Goldie; Gaudion, Michele (ill.) Lame Duck Protest 978-1-921479-13-7 3-4 Allaby, Michael DK Guide to Weather 978-0-7513-2856-1 3-4 Allen, Emma; Blackwood, Freya (ill.) The Terrible Suitcase 9781862919402 EC-2, 3-4 Allen, Judy Anthology for the Earth 978-0-7636-0301-4 3-4 Allen, Scott Jesse the Elephant 9781921638138 3-4 Almond, David; Pinfold, Levi (ill.) The Dam 9781406304879 EC-2, 3-4 Almond, David; Smith, Alex T. The Tale of Angelino Brown 9781406358070 3-4, 5-6 Amadio, Nadine; Blackman, Charles (ill.) The New Adventures of Alice in Rainforest Land 978-0-949284-07-5 3-4 Andreae, Giles; Sharrat, Nick (ill.) Billy Bonkers series 3-4 Anholt, Laurence Camille and the Sunflowers 978-0-7112-1050-9 3-4 Anholt, Laurence Frida Kahlo and the Bravest Girl in the World 9781847806666 3-4 Anna Ciddor A Roman Day to Remember 978-0816767960 -

Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature

Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature By Derek M. Ettensohn M.A., Brown University, 2012 B.A., Haverford College, 2006 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Derek M. Ettensohn This dissertation by Derek M. Ettensohn is accepted in its present form by the Department of English as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date ___________________ _________________________ Olakunle George, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ___________________ _________________________ Timothy Bewes, Reader Date ___________________ _________________________ Ravit Reichman, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date ___________________ __________________________________ Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Abstract of “Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature” by Derek M. Ettensohn, Ph.D., Brown University, May 2014. This project evaluates the twinned discourses of globalism and humanitarianism through an analysis of the body in the postcolonial novel. In offering celebratory accounts of the promises of globalization, recent movements in critical theory have privileged the cosmopolitan, transnational, and global over the postcolonial. Recognizing the potential pitfalls of globalism, these theorists have often turned to transnational fiction as supplying a corrective dose of humanitarian sentiment that guards a global affective community against the potential exploitations and excesses of neoliberalism. While authors such as Amitav Ghosh, Nuruddin Farah, and Rohinton Mistry have been read in a transnational, cosmopolitan framework––which they have often courted and constructed––I argue that their theorizations of the body contain a critical, postcolonial rejoinder to the liberal humanist tradition that they seek to critique from within. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Artxsr, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* NOTE TO USERS Page(s) missing in number only; text follows. Page(s) were microfilmed as received. 131,172 This reproduction is the best copy available UMI FRANK WEDEKIND’S FANTASY WORLD: A THEATER OF SEXUALITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Bv Stephanie E. -

Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic

‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Irene Bulla All rights reserved ABSTRACT ‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla This dissertation analyzes the ways in which monstrosity is articulated in fantastic literature, a genre or mode that is inherently devoted to the challenge of representing the unrepresentable. Through the readings of a number of nineteenth-century texts and the analysis of the fiction of two twentieth-century writers (H. P. Lovecraft and Tommaso Landolfi), I show how the intersection of the monstrous theme with the fantastic literary mode forces us to consider how a third term, that of language, intervenes in many guises in the negotiation of the relationship between humanity and monstrosity. I argue that fantastic texts engage with monstrosity as a linguistic problem, using it to explore the limits of discourse and constructing through it a specific language for the indescribable. The monster is framed as a bizarre, uninterpretable sign, whose disruptive presence in the text hints towards a critique of overconfident rational constructions of ‘reality’ and the self. The dissertation is divided into three main sections. The first reconstructs the critical debate surrounding fantastic literature – a decades-long effort of definition modeling the same tension staged by the literary fantastic; the second offers a focused reading of three short stories from the second half of the nineteenth century (“What Was It?,” 1859, by Fitz-James O’Brien, the second version of “Le Horla,” 1887, by Guy de Maupassant, and “The Damned Thing,” 1893, by Ambrose Bierce) in light of the organizing principle of apophasis; the last section investigates the notion of monstrous language in the fiction of H. -

99 Essential African Books: the Geoff Wisner Interview

99 ESSENTIAL AFRICAN BOOKS: THE GEOFF WISNER INTERVIEW Interview by Scott Esposito Tags: African literature, interviews Discussed in this interview: • A Basket of Leaves: 99 Books that Capture the Spirit of Africa, Geoff Wisner. Jacana Media. $25.95. 292 pp. Although it is certain to one day be outmoded by Africa’s ever-changing national boundaries, for now Geoff Wisner’s book A Basket of Leaves offers a guide to literature from every country in the African continent. Wisner reviews 99 books total, covering the biggest homegrown authors (Achebe, Coetzee, Ngugi), some notable foreigners (Kapuscinski, Chatwin, Bowles), and a host of lesser-knowns. The books were selected from hundreds of works of African literature that Wisner has read: how to whittle hundreds down to just 99 books to represent an entire continent? Wisner says reading widely was key, as was developing a “bullshit detector” for the “false” and “fraudulent” in African lit by living there and working with the legal defense of political prisoners in South Africa and Nambia. Full of sharp opinions and oft-overlooked gems, A Basket of Leaves offers a compelling overview of a continent and its literature—an overview one that Wisner is eager to supplement and discuss in person. —Scott Esposito Scott Esposito: To start, how did you conceive and develop A Basket of Leaves? Geoff Wisner: The idea developed rather slowly. For several years I was raising money for political prisoners in South Africa and Namibia. I edited a newsletter on Southern Africa and started to read authors like Nadine Gordimer and J.M. -

Research Degree and Professional Doctorate Students Output (July

RESEARCH DEGREE AND PROFESSIONAL DOCTORATE STUDENTS’ RESEARCH OUTPUT (July 2013 – June 2014) This report summarizes the research outputs of our research degree and professional doctorate students, and serves to recognize their hard work and perseverance. It also acts as a link between the University and the community, as it demonstrates the excellent research results that can benefit the development of the region. Chow Yei Ching School of Graduate Studies February 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OF RESEARCH OUTPUT PRODUCED BY PHD STUDENTS IN 2013-2014 ............................... IV SUMMARY OF RESEARCH OUTPUT PRODUCED BY MPHIL STUDENTS IN 2013-2014 ............................. V SUMMARY OF RESEARCH OUTPUT PRODUCED BY PROFESSIONAL DOCTORATE STUDENTS IN 2013- 2014 ............................................................................................................................................ VI SECTION A: PUBLICATIONS OF PHD STUDENTS ................................................................................... 7 COLLEGE OF BUSINESS .................................................................................................................................... 7 DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTANCY ......................................................................................................................... 7 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE ....................................................................................................... 7 DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS .......................................................................................................... -

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Research The

G a b r i e l l a | 1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of The Research The idea of gender inequality has always been a big issue of human rights. In the nineteenth-century, women lived in different spheres or circumstances that separate them from men. And in fact, there were only a few women who are able to get good education or to pursue their career. However, at the beginning of the nineteenth-century women have begun to fight for their rights until now. In today’s society, we are able to see women getting their rights to vote, or to pursue their career, but in fact gender equality has not achieved yet. In September 2014, United Nation Women Goodwill Ambassador, Emma Watson made her speech about gender equality, she said “No country in the world can yet say that they achieved gender equality” (Watson). The idea of gender equality is to give women their full potential in every aspect of life, being equal without any gender boundaries. However, Emma Watson speech has captured the issue of women’s struggle, not only from Emma, the writer also found the women’s struggle is interpreted by different perspective, Michelle Obama in her speech during her visit in Argentina said “As I got older, I found that men would whistle at me as I walked down the street, as G a b r i e l l a | 2 if my body were their property, as if I were an object to be commented on instead of a full human being with thoughts and feelings of my own” (Obama). -

Acatech MATERIALIEN Industry 4.0 and Urban Development the Case

Industry 4.0 and Urban Development The Case of India Bernhard Müller/Otthein Herzog acatech MATERIALIEN Authors/Editors: Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Bernhard Müller Prof. Dr. Otthein Herzog Technische Universität Dresden und Universität Bremen und Leibniz-Institut für ökologische Raumentwicklung (IÖR) Jacobs University Bremen Weberplatz 1 Am Fallturm 1 01217 Dresden 28359 Bremen E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Project: GIZ SV IKT Projekt Advanced Manufacturing und Stadtentwicklung Project term: 12/2013-09/2014 The project was financed by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (support code 01/S10032A). Series published by: acatech – NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING, 2015 Munich Office Berlin Office Brussels Office Residenz München Unter den Linden 14 Rue d’Egmont/Egmontstraat 13 Hofgartenstraße 2 10117 Berlin 1000 Brüssel 80539 Munich Belgium T +49 (0) 89 / 5 20 30 90 T +49 (0) 30 / 2 06 30 96 0 T +32 (0) 2 / 2 13 81 80 F +49 (0) 89 / 5 20 30 99 F +49 (0) 30 / 2 06 30 96 11 F +32 (0) 2 / 2 13 81 89 E-Mail: [email protected] Web site: www.acatech.de © acatech – NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING, 2015 Coordination: Dr. Karin-Irene Eiermann Rework: IÖR A. S. Hering, K. Ludewig, K. Kohnen, S. Witschas Layout-Concept: acatech Conversion and typesetting: Fraunhofer-Institut für Intelligente Analyse- und Informationssysteme IAIS, Sankt Augustin > THE acatech MATERIALS SERIES This series publishes discussion papers, presentations and preliminary studies arising in connection with acatech‘s project work. Responsibility for the content of the volumes published as part of this series lies with their respective editors and authors. -

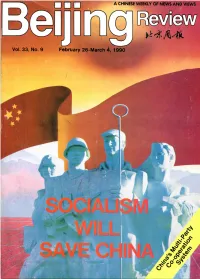

China's NOTES from the EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who with National Culture

—Inspired by the Lei Feng* spirit of serving the people, primary school pupils of Harbin City often do public cleanups on their Sunday holidays despite severe winter temperature below zero 20°C. Photo by Men Suxian * Lei Feng was a squad leader of a Shenyang unit of the People's Liberation Army who died on August 15, 1962 while on duty. His practice of wholeheartedly serving the people in his ordinary post has become an example for all Chinese people, especially youfhs. Beijing««v!r VOL. 33, NO. 9 FEB. 26-MAR. 4, 1990 Carrying Forward the Cultural Heritage CONTENTS • In a January 10 speech. CPC Politburo member Li Ruihuan stressed the importance of promoting China's NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who With national culture. Li said this will help strengthen the coun• Sanctions? try's sense of national identity, create the wherewithal to better resist foreign pressures, and reinforce national cohe• EVENTS/TRENDS 5 8 sion (p. 19). Hong Kong Basic Law Finalized Economic Zones Vital to China NPC to Meet in March Sanctions Will Get Nowhere Minister Stresses Inter-Ethnic Unity • Some Western politicians, in defiance of the reahties and Dalai's Threat Seen as Senseless the interests of both China and their own countries, are still Farmers Pin Hopes On Scientific demanding economic sanctions against China. They ignore Farming the fact that sanctions hurt their own interests as well as 194 AIDS Cases Discovered in China's (p. 4). China INTERNATIONAL Upholding the Five Principles of Socialism Will Save China Peaceful Coexistence 9 Mandela's Release: A Wise Step o This is the first instalment of a six-part series contributed Forward 13 by a Chinese student studying in the United States.