Helmut Lachenmann String Quartets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

Juilliard String Quartet

JUILLIARD STRING QUARTET ARETA ZHULLA - VIOLIN RONALD COPES - VIOLIN ROGER TAPPING - VIOLA ASTRID SCHWEEN - VIOLONCELLO „Decisive and uncompromising...Juilliard’s confidently thoughtful approach, rhythmic acuity and ensemble precision were on full display." – The Washington Post With unparalleled artistry and enduring vigor, the Juilliard String Quartet continues to inspire audiences around the world. Founded in 1946 and hailed by the Boston Globe as “the most important American quartet in history,” the Juilliard draws on a deep and vital engagement to the classics, while embracing the mission of championing new works, a vibrant combination of the familiar and the daring. Each performance of the Juilliard Quartet is a unique experience, bringing together the four members’ profound understanding, total commitment, and unceasing curiosity in sharing the wonders of the string quartet literature. Ms. Areta Zhulla joins the Juilliard Quartet as first violinist beginning this 2018-19 season which includes concerts in Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, London, Oslo, Athens, Vancouver, Toronto and New York, with many return engagements all over the USA. The season will also introduce a newly commissioned String Quartet by the wonderful young composer, Lembit Beecher, and some piano quintet collaborations with the celebrated Marc-André Hamelin. In performance, recordings and incomparable work educating the major artists and quartets of our time, the Juilliard String Quartet has carried the banner of the United States and the Juilliard School throughout the world. Having recently celebrated its 70th anniversary, the Juilliard String Quartet marked the 2017-18 season with return appearances in Seattle, Santa Barbara, Pasadena, Memphis, Raleigh, Houston, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen. It continued its acclaimed annual performances in Detroit and Philadelphia, along with numerous concerts at home in New York City, including appearances at Lincoln Center and Town Hall. -

Marshall University Music Department Presents

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar All Performances Performance Collection Fall 11-7-2008 Marshall University Music Department Presents, Music Alive Series, Graffe trS ing Quartet, Štĕpán Graffe, violin, Lukáš Bednařik, violin, Lukáš Cybulski, viola, Michal Hreno, violoncello, with, Michiko Otaki, piano Michiko Otaki Štĕpán Graffe Lukáš Bednařik Lukáš Cybulski Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Otaki, Michiko; Graffe, Štĕpán; Bednařik, Lukáš; and Cybulski, Lukáš, "Marshall University Music Department Presents, Music Alive Series, Graffe trS ing Quartet, Štĕpán Graffe, violin, Lukáš Bednařik, violin, Lukáš Cybulski, viola, Michal Hreno, violoncello, with, Michiko Otaki, piano" (2008). All Performances. 752. http://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf/752 This Recital is brought to you for free and open access by the Performance Collection at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Performances by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DEPARTMENT of MUSIC Program String Quartet in g min.or, Franz Joseph Haydn op. 74, no. 3 ("Rider") (1732-1809) Allegro moderate MUSIC Largo assai Menuetto: Allegretto Finale: Allegro con brio presents the Quintet for Piano and Strings Robert Schumann Music Alive Series in E-flat major, op. 44 (1810-1856) Allegro brillante In modo d'una marcia GRAFFE STRING QUARTET Scherzo: Molto vivace Stepan Graffe, violin Allegro ma non troppo Lukas Bednarik, violin Lukas Cybulski, viola Michiko Otaki, piano Michal Hreno, violoncello with Michiko Otaki, piano Friday, November 7, 2008 Exclusive Management for the First Presbyterian Church GRAFFE QUARTET and MICHIKO OTAKI: 12:00 p.m. -

Juilliard String Quartet Areta Zhulla and Ronald Copes, Violins Roger Tapping, Viola Astrid Schween, Cello

Thursday Evening, December 12, 2019, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard String Quartet Areta Zhulla and Ronald Copes, Violins Roger Tapping, Viola Astrid Schween, Cello LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18, No. 1 Allegro con brio Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegro GYÖRGY KURTÁG (b. 1926) 6 Moments musicaux, Op. 44 Invocatio (Un fragment) Footfalls (… as if someone were coming) Capriccio In memoriam Sebok˝ György Rappel des oiseaux ... (Étude pour les harmoniques) Les adieux (in Janáceks˘ Manier) Intermission BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131 Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo Allegro molto vivace Allegro moderato—Adagio Andante, ma non troppo e molto cantabile Presto Adagio quasi un poco andante Allegro Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including an intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program published, in 1801. The D-major quartet (Op. 18, No. 3) was the first to be written; the By James M. Keller F-major (No. 1) and G-major (No. 2) followed, probably in that order; and the A major String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18, (No. 5), C minor (No. -

String Quartet 2 Notes.Odt

i Notes on the Scordatura Tuning This string quartet is written in an 11-limit just intonation system based on a Bb fundamental. To facilitate this a scordatura system has been designed wherein the strings of each instrument are tuned to harmonics of the Bb overtone series. The base ratios for each pitch are listed in the table below with their corresponding cent values relative to the fundamental. They are ordered by their distance from the fundamental. Pitch Bb Db D E1/4b F Ab Ratio and 1/1 = 0 c 7/6 = 266.8 c 5/4 = 386.3 c 11/8 = 551.3 c 3/2 = 702 c 7/4 = 968.8 c Cents (c) To further facilitate the scordatura tuning the following chart shows the desired frequency values in Hertz (Hz) for each string on each instrument. Instrument String IV String III String II String I Cello Bb 1 = 58.27 Hz F 2 = 87.405 Hz D 3 = 145.675 Hz Ab 3 = 203.945 Hz Viola Bb 2 = 116.54 Hz F 3 = 174.81 Hz Db 4 = 271.927 Hz Ab 4 = 407.89 Hz Violin II F 3 = 174.81 Hz Db 4 = 271.927 Hz Ab 4 = 407.89 Hz E1/4b = 640.97 Hz Violin I F 3 = 174.81 Hz D 4 = 291.35 Hz Ab 4 = 407.89 Hz E1/4b = 640.97 Hz The Cellist should tune their C string down to the desired Bb fundamental. Then they should tune the other strings to the 3rd (F), 5th (D), 7th (Ab) and 11th (E1/4b) harmonics of the "Bb string." Once all of the players have tuned their strings which correspond to harmonics of the Bb overtone series the second Violin and the Viola may tune the D string down to the 7/6 Db minor third by tuning it as a perfect 5th below the Ab string (7/4). -

Danish String Quartet Frederik Øland, Violin | Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, Violin Asbjørn Nørgaard, Viola | Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, Cello

PRESENTS Danish String Quartet Frederik Øland, violin | Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violin Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola | Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello ChamberMusicConcerts.org · 541-552-6154 DANISH STRING QUARTET FRIDAY, APRIL 16, 2021 – 7:30PM Recorded in Denmark for Chamber Music Concerts Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) String Quartet in D Major, Op. 18 no. 3 Allegro Andante con moto Allegro Presto Scandinavian Folk Music (Traditional, arranged by the Danish Quartet) “Ye honest bridal couple”/ Sønderho bridal trilogy part 1/ Sønderho bridal trilogy part 2 Six tour from vendsyssel / “the peat dance” “Easter Sunday”/ Polsk after Rasmus Storm “Stædelil” “Halling after halteguten” “Regin smidur” “Five sheep, four goats” “Shine you no more” PLATINUM SPONSOR: Anne C. Diller gold sponsors: Chris Donchin, Gary & Coralie Farnham, Jeanette Larson, Louis Roemer & Karen Gernant silver sponsors: John & Kay Johnson, Fred & Laura Perloff, Sandra Sobol & Jon Holtzman, Thomas & Cynthia Stauffer online producer/director: OurConcerts.Live Exclusive Representation: Kirshbaum Associates Inc. 711 West End Avenue, Suite 5KN, New York, NY 10025 www.kirshbaumassociates.com The Danish String Quartet is currently exclusive with ECM Records and has previously recorded for DaCapo and Cavi-Music/BR Klassik Danish String Quartet Frederik Øland, violin | Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violin Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola | Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello mong today’s many exceptional chamber music groups, the GRAMMY® nom- A inated Danish String Quartet continuously asserts its preeminence. The Quar- tet’s playing reflects impeccable musicianship, sophisticated artistry, exquisite clarity of ensemble, and, above all, an expressivity inextricably bound to the music, from Haydn to Shostakovich to contemporary scores. Performances bring a rare musical spontaneity, giving audiences the sense of hearing even treasured canon repertoire as if for the first time, and exuding a palpable joy in musicmaking that have made them enormously in-demand on concert stages throughout the world. -

Symposium Records Cd 1109 Adolf Busch

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1109 The Great Violinists – Volume 4 ADOLF BUSCH (1891-1952) This compact disc documents the early instrumental records of the greatest German-born musician of this century. Adolf Busch was a legendary violinist as well as a composer, organiser of chamber orchestras, founder of festivals, talented amateur painter and moving spirit of three ensembles: the Busch Quartet, the Busch Trio and the Busch/Serkin Duo. He was also a great man, who almost alone among German gentile musicians stood out against Hitler. His concerts between the wars inspired a generation of music-lovers and musicians; and his influence continued after his death through the Marlboro Festival in Vermont, which he founded in 1950. His associate and son-in-law, Rudolf Serkin (1903-1991) maintained it until his own death, and it is still going strong. Busch's importance as a fiddler was all the greater, because he was the last glory of the short-lived German school; Georg Kulenkampff predeceased him and Hitler's decade smashed the edifice built up by men like Joseph Joachim and Carl Flesch. Adolf Busch's career was interrupted by two wars; and his decision to boycott his native country in 1933, when he could have stayed and prospered as others did, further fractured the continuity of his life. That one action made him an exile, cost him the precious cultural nourishment of his native land and deprived him of his most devoted audience. Five years later, he renounced all his concerts in Italy in protest at Mussolini's anti-semitic laws. -

ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet and ODU Cello Choir

Program String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Alexander Borodin 1. Allegro Moderato (1833-1887) 3. Notturno - Andante The ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet Jordan Goodmurphy, Violin Emily Pollard, Violin F. Ludwig Diehn School of Music Joshua Clarke, Viola Michael Russo, Cello Trio in C Major, Op. 87 for Three Cellos L.V. Beethoven 3. Minuetto-Allegro molto scherzo. Trio. (1770-1827) trans. A.C. Prell ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet ODU Cello Choir Requiem, Op. 66 for Three Cellos and Piano David Popper Andante Sostenuto (1843-1913) Leslie J. Frittelli, director Carter Campbell, piano Sonata No. 1 in A Major for Three Cellos Arcangelo Corelli 1. Grave (1653-1713) 2. Allegro arr. Erinn Renyer 3. Adagio 4. Allegro ODU Cello Choir Carter Campbell Diehn Center for the Performing Arts Trinity Green Chandler Recital Hall Joshua Kahn Lexi McGinn Avery Suhay Aleta Tomas Lacey Wilson Friday, November 22, 2019 7:30 pm Program String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Alexander Borodin 1. Allegro Moderato (1833-1887) 3. Notturno - Andante The ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet Jordan Goodmurphy, Violin Emily Pollard, Violin F. Ludwig Diehn School of Music Joshua Clarke, Viola Michael Russo, Cello Trio in C Major, Op. 87 for Three Cellos L.V. Beethoven 3. Minuetto-Allegro molto scherzo. Trio. (1770-1827) trans. A.C. Prell ODU Russell Stanger String Quartet ODU Cello Choir Requiem, Op. 66 for Three Cellos and Piano David Popper Andante Sostenuto (1843-1913) Leslie J. Frittelli, director Carter Campbell, piano Sonata No. 1 in A Major for Three Cellos Arcangelo Corelli 1. Grave (1653-1713) 2. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

For Immediate Release

For Immediate Release THE GUARNERI STRING QUARTET WILL CELEBRATE ITS 40TH ANNIVERSARY BY GIVING A GIFT TO THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK CITY – A SERIES OF EVENTS AT LINCOLN CENTER, MONDAY AND TUESDAY, APRIL 11 AND 12, FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC PANEL DISCUSSION, MASTER CLASS AND OPEN REHEARSAL WILL CONTINUE THE GUARNERI’S 40TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATIONS The world-renowned Guarneri String Quartet, one of the most esteemed and beloved ensembles of our time, will continue its 40th anniversary celebration by giving a gift to the people of New York City: a series of three events on Monday and Tuesday, April 11 and 12, in the Daniel and Joanna S. Rose Rehearsal Studio of Lincoln Center, which will be free and open to the public. The events include a master class involving top young string quartets from The Juilliard School, the Curtis Institute of Music, and the Manhattan School of Music; an open rehearsal for the Guarneri String Quartet’s Alice Tully Hall concert on April 13 presented by The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center; and a panel discussion with the members of the Guarneri Quartet, veteran members of historic string quartets, and members of the newest quartet generation. All three events will be held in the Rose Studio of the Rose Building (165 West 65th Street, 10th Floor; 65th Street and Amsterdam Avenue) and are free and open to the public on a first-come, first-served basis. Members of the Guarneri String Quartet are Arnold Steinhardt and John Dalley, violins; Michael Tree, viola; and Peter Wiley, cello. -

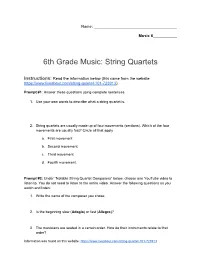

6Th Grade Music: String Quartets

Name: ______________________________________ Music 6___________ 6th Grade Music: String Quartets Instructions: Read the information below (this came from the website https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913). Prompt #1: Answer these questions using complete sentences. 1. Use your own words to describe what a string quartet is. 2. String quartets are usually made up of four movements (sections). Which of the four movements are usually fast? Circle all that apply a. First movement b. Second movement c. Third movement d. Fourth movement. Prompt #2: Under “Notable String Quartet Composers” below, choose one YouTube video to listen to. You do not need to listen to the entire video. Answer the following questions as you watch and listen: 1. Write the name of the composer you chose. 2. Is the beginning slow (Adagio) or fast (Allegro)? 3. The musicians are seated in a certain order. How do their instruments relate to that order? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 4. How do the musicians respond to each other while playing? Prompt #3: Under Modern String Quartet Music, find the Love Story quartet by Taylor Swift. Listen to it as you answer using complete sentences. 1. Which instrument is plucking at the beginning of the piece? (If you forgot, violins are the smallest instrument, violas are a little bigger, cellos are bigger and lean on the floor). 2. Reflect on how this version of Love Story is different from Taylor Swift’s original song. How would you describe the differences? What does this version communicate? Information was found on this website: https://www.liveabout.com/string-quartet-101-723913 String Quartet 101 All You Need to Know About the String Quartet The Jerusalem Quartet, a string quartet made of members (from left) Alexander Pavlovsky, Sergei Bresler, Kyril Zlontnikov and Ori Kam, perform Brahms’s String Quartet in A minor at the 92nd Street Y on Saturday night, October 25, 2014. -

Cavani String Quartet

Cavani String Quartet Described by the Washington Post as “completely engrossing powerful and elegant” The Cavani Quartet has dedicated its artistic life to communicating the joy of discovery in the service of some of the most powerful music ever written. "Their artistic excellence, their generous spirit, and their fervent ambassadorship for great music make them unique among America's greatest string quartets. They may be the single most valuable role model for the classical chamber music field in our time, an inspiration to fellow musicians and audiences across the country." ~Detroit Chamber Music Society The quartet's musical career maintains an energetic balance between performing masterpieces by composers such as Mozart, Beethoven and Bartok; collaborating with living composers including Joan Tower and Margaret Brouwer; and creating new programming that joins multiple disciplines, such as visual art, poetry, and dance.The quartet’s motivation to interact with all audiences enhances their approach to performing, teaching and mentoring. The Cavani Quartet is thrilled to shape the musical lives of the next generation through seminars that feature audience engagement and a "team -work" approach to rehearsal techniques. The empathy and connectivity of chamber music is recognized by the Cavani Quartet as a metaphor for the kind of communication that we should strive for between cultures and nations. Formed in 1984, the Cavani Quartet has toured throughout all fifty states, performing at some of the worlds most prestigious festivals, and series including The Aspen Music Festival, The New World Symphony, Norfolk Chamber Music Festival, Kniesel Hall, Interlochen Center for the Arts, Madeline Island Music Festival, The Chautauqua Festival, Encore Chamber Music and The Perlman Music Program.