On Some Possible New Relations in the ʽsomerton Manʼ Or ʽtamám Shudʼ Case Author: Rowan Holmes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

On the Beach 4 5 by Nevil Shute 6

Penguin Readers Factsheets l e v e l E T e a c h e r’s n o t e s 1 2 3 On the Beach 4 5 by Nevil Shute 6 INTERMEDIATE S U M M A R Y n the Beach was first published in 1957. It was made BACKGROUND AND THEMES O into a film in 1959 starring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Fred Astaire. The story is set in the fictional future, In 1957, when On the Beach was published, nuclear war was and assumes that an atomic war has taken place. The atomic at the forefront of people’s minds. The Cold War between the bombs and the fall-out have destroyed the nort h e rn E a s t e rn block and the West made the danger of war hemisphere of the world. The radioactive dust is slowly moving frighteningly real, as both sides gathered arms and threatened south, killing everything in its path. Lieutenant Commander in each other. The world seemed more vulnerable than ever the Australian navy, Peter Holmes, is appointed liaison officer before, and On the Beach dealt with issues few people were on board Scorpion, an atomic submarine. He is to work under prepared to confront. American Commander, Dwight Towers. The submarine is sent on a short journey to investigate the eastern and northern Shute was convinced that On the Beach was going to be a coasts of Australia, and a longer cruise to the north to failure, and was pleasantly surprised when it proved to be a determine if there is any sign of life. -

Teacher's Notes

PENGUIN READERS Teacher’s notes LEVEL 4 Teacher Support Programme On the Beach Nevil Shute Summary On the Beach was first published in 1957. It was made into a film in 1959 starring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Fred Astaire. The story is set in a fictional future, and assumes that a nuclear war has taken place. The nuclear bombs and the fallout have destroyed the northern hemisphere of the world. The radioactive dust is slowly moving south, killing everything in its path. Peter Holmes, Lieutenant Commander in the Australian navy, is appointed liaison officer on board Scorpion, a nuclear submarine. He is to work under American Commander, Dwight Towers. The submarine is sent on a short journey to investigate the eastern and northern coasts of Australia, About the author and a longer cruise to the north to determine if there is Nevil Shute Norway was born on 17 January 1899 in any sign of life. The story focuses on five main characters Ealing, a suburb of London, which was then at the edge – Peter, his wife, Mary, and baby daughter, Jennifer, their of the country. Shute had a lifelong passion for aeroplanes friend, Moira, and Dwight Towers. It shows how they face and said they were ‘the best part of my life.’ Playing impending disaster, and how they personally confront the truant from his hated Hammersmith prep school, Shute fate that awaits them. would visit the Science Museum in Kensington, where he Background and themes immersed himself amongst the model aeroplanes. Threat of nuclear war: In 1957, when On the Beach was Shute’s elder brother, Fred, died at the age of nineteen published, nuclear war was at the forefront of people’s in the First World War. -

The Main Characters' Committing Suicide

THE MAIN CHARACTERS’ COMMITTING SUICIDE ON NEVIL SHUTE’S ON THE BEACH: A MORAL PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By LINA PERMANASARI Student Number: 034214099 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2008 i LIFE IS A GAME, PLAY IT LIFE IS A CHALLENGE, MEET IT LIFE IS AN OPPORTUNITY, CAPTURE IT (Anonymous) iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Firstly, I would give my deepest gratitude to Jesus and His lovely mother, Mary who give me spirit in my difficult time. They put a big part in helping me finishing my thesis, without their blessing I would not finish my thesis. My deepest gratefulness is given to my advisor, Modesta Luluk Artika, S. S, without her my thesis would never be like this. I thank her for giving me advices and criticisms for my thesis. She always encourages me in finishing my thesis when I feel tired to finish my thesis. I’m sorry that I cannot accomplish your target date to finish my thesis. I thank for your kindness for allowing me to have consultation at your home. I also deeply thank to my co-advisor, Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, S. S, M. Hum., who helps me in correcting the idea of this thesis. Thanks for your advices and also all materials that you taught during my study. I thank to my examiner, Elisa Dwi Wardani, S.S, M.Hum., for giving me many advices in for my thesis. -

Remembering on the Beach

A COMMENTARY BY PHILIP BEIDLER Remembering On the Beach efore World War II, Hollywood scared people to death with mad scientists and monsters. During World War II they specialized in strutting Nazis and villainous Japs. After the war, political subversives mixed with Bspace creatures, and vice versa; as importantly, in what had come to be called the nuclear age, a whole new category of fear film centered on atomic mutants: Them; Godzilla; Attack of the Crab Monsters; It Came From Beneath the Sea. More directly, Invasion USA. (1952) combined fear of nuclear attack with communist takeover, helping to usher in the new Cold War genre of Soviet/US atomic mass destruction movies culminating in such boomer classics as Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove, both issued in 1964. Less frequently remembered, perhaps because slightly older—albeit now decidedly more interesting for its emphasis on the human depiction of nuclear aftermath than on the Pentagon-Kremlin mechanics of initiating wars of mutual annihilation—is the one that first got the attention of popular audiences on the subject. That would beOn the Beach (1959), Stanley Kramer’s elegiac representation of the dying remnant of a world in the wake of global atomic warfare. In the golden age of Technicolor and Cinemascope—and to this degree anticipating its better known successors—it was a black-and-white film of stark, muted, austere genius, featuring career performances from a number of important actors: Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, a pre-Psycho Anthony Perkins, and Fred Astaire, in his first purely dramatic role. In all these respects, it became a movie that challenged people who saw it never to look at the world in the same way again. -

The Social Costs of Marine Litter Along the East China Sea: Evidence from Ten Coastal Scenic Spots of Zhejiang Province, China

sustainability Article The Social Costs of Marine Litter along the East China Sea: Evidence from Ten Coastal Scenic Spots of Zhejiang Province, China Manhong Shen 1,2, Di Mao 1 , Huiming Xie 2,* and Chuanzhong Li 3 1 School of Economics, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (D.M.) 2 School of Business, Ningbo University, Ningbo 315211, China 3 Department of Economics, University of Uppsala, 751 20 Uppsala, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 February 2019; Accepted: 18 March 2019; Published: 25 March 2019 Abstract: Marine litter poses numerous threats to the global environment. To estimate the social costs of marine litter in China, two stated preference methods, namely the contingent valuation model (CVM) and the choice experiment model (CEM), were used in this research. This paper conducted surveys at ten different beaches along the East China Sea in Zhejiang province in October 2017. The results indicate that approximately 74.1% of the interviewees are willing to volunteer to participate in clean-up programmes and are willing to spend 1.5 days per month on average in their daily lives, which equates to a potential loss of income of USD 1.08 per day. The willingness to pay for the removal of the main types of litter ranges from USD 0.12–0.20 per visitor across the four sample cities, which is mainly determined by the degree of the removal, the crowdedness of the beach and the visitor’s perception. The social costs are USD 1.08–1.40 per visitor when the contingent valuation method is applied and USD 1.00–1.07 per visitor when the choice experiment method is adopted, which accounts for 8–14% of the beach entrance fee. -

Download on the Beach Pdf Ebook by Nevil Shute

Download On the Beach pdf ebook by Nevil Shute You're readind a review On the Beach book. To get able to download On the Beach you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Ebook File Details: Original title: On the Beach 320 pages Publisher: Vintage; 1 edition (2010) Language: English ISBN-10: 0307473996 ISBN-13: 978-0307473998 Product Dimensions:5.2 x 0.7 x 8 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 11159 kB Description: Nevil Shute’s most powerful novel—a bestseller for decades after its 1957 publication—is an unforgettable vision of a post-apocalyptic world.After a nuclear World War III has destroyed most of the globe, the few remaining survivors in southern Australia await the radioactive cloud that is heading their way and bringing certain death to everyone in its... Review: This copy (produced by Amazon LLC) is not in fact the actual book by Nevil Shute, but a poor abridgement of it. It clocked in at 207 pages, 23 lines per page, versus 320 pages at 33 lines per page in my 1957 edition. It reads like the book condensed for English language learners. First line, second paragraph, has gone from He woke happy, and it... Book File Tags: nuclear war pdf, nevil shute pdf, northern hemisphere pdf, cold war pdf, end of the world pdf, years ago pdf, read this book pdf, southern hemisphere pdf, dwight towers pdf, well written pdf, high school pdf, going to die pdf, thought provoking pdf, kindle version pdf, even though pdf, nuclear holocaust pdf, science fiction pdf, alas babylon pdf, nuclear weapons pdf, peter holmes On the Beach pdf ebook by Nevil Shute in Science Fiction and Fantasy Science Fiction and Fantasy pdf ebooks On the Beach on the beach ebook on beach the book the on beach fb2 the on beach pdf On the Beach Beach On the This last book, however, read as if it was never edited. -

Beachcombers Field Guide

Beachcombers Field Guide The Beachcombers Field Guide has been made possible through funding from Coastwest and the Western Australian Planning Commission, and the Department of Fisheries, Government of Western Australia. The project would not have been possible without our community partners – Friends of Marmion Marine Park and Padbury Senior High School. Special thanks to Sue Morrison, Jane Fromont, Andrew Hosie and Shirley Slack- Smith from the Western Australian Museum and John Huisman for editing the fi eld guide. FRIENDS OF Acknowledgements The Beachcombers Field Guide is an easy to use identifi cation tool that describes some of the more common items you may fi nd while beachcombing. For easy reference, items are split into four simple groups: • Chordates (mainly vertebrates – animals with a backbone); • Invertebrates (animals without a backbone); • Seagrasses and algae; and • Unusual fi nds! Chordates and invertebrates are then split into their relevant phylum and class. PhylaPerth include:Beachcomber Field Guide • Chordata (e.g. fi sh) • Porifera (sponges) • Bryozoa (e.g. lace corals) • Mollusca (e.g. snails) • Cnidaria (e.g. sea jellies) • Arthropoda (e.g. crabs) • Annelida (e.g. tube worms) • Echinodermata (e.g. sea stars) Beachcombing Basics • Wear sun protective clothing, including a hat and sunscreen. • Take a bottle of water – it can get hot out in the sun! • Take a hand lens or magnifying glass for closer inspection. • Be careful when picking items up – you never know what could be hiding inside, or what might sting you! • Help the environment and take any rubbish safely home with you – recycle or place it in the bin. Perth• Take Beachcomber your camera Fieldto help Guide you to capture memories of your fi nds. -

'There's Camels on the Beach!' the Nine Mile Beach, Central Queensland Macrotidal Beach Experiment

Brander, Masselink, and Turner ‘There’s Camels on the Beach!’ The Nine Mile Beach, Central Queensland Macrotidal Beach Experiment Robert W. Brander1*, Gerd Masselink2, and Ian L. Turner3 1School of Biological Sciences, UNSW Sydney, NSW, Australia 2School of Biological and Marine Sciences, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK 3Water Research Laboratory, UNSW Sydney, NSW, Australia It often seems that the more remote and environmentally challenging coastal fieldwork is, the more memorable the experiences and resulting stories become, and it is not uncommon for strong lifetime bonds, both professionally and personally, to form between the fieldworkers involved. While this is not always the case, it is certainly true of the field experiments conducted by the Coastal Studies Unit of the University of Sydney on Nine Mile Beach, Queensland, Australia in February 1992 (Figure 1a). a b Figure 1. (a) Nine Mile Beach, Queensland taken from the headland at the southern end of the beach. The field site is towards the far end of the beach in this photograph. (Photo: R.W. Brander.) (b) Low tide bar and rip beach state morphology at Nine Mile Beach in early February 1992. Dye release shows a rip current while the field camp is on the foredune, roughly in the middle of the picture. (Photo: A.D. Short.) The experiments were part of the Australian Macrotidal Beach and Estuarine Research Project (AMBER) and were led by Gerd Masselink and Ian Turner, who at the time were Ph.D. students under the supervision of Dr. Andy Short. Both were studying macrotidal beaches and six months earlier had conducted a fruitful reconnaissance of the Queensland macrotidal coastline, surveying a plethora of macrotidal beaches in Queensland that contributed significantly to the development of the macrotidal beach model (Masselink, 1993; Masselink and Short, 1993). -

Spirit of Antarctica

Spirit of Antarctica 07 – 16 January 2019 | Polar Pioneer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild and adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of naturalists, historians remote places on our planet. With over 25 years’ experience, our small group voyages allow and destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they are the secret to a for a truly intimate experience with nature. fulfilling and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting wildlife Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group of like-minded education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every opportunity for lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild and adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of naturalists, historians and remote places on our planet. With over 27 years’ experience, our small group voyages allow for destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they are the secret to a fulfilling a truly intimate experience with nature. and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting wildlife Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group of like-minded education and preservation of the environment. -

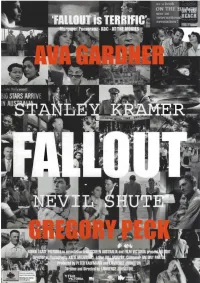

Reviews of Fallout

REVIEWS OF FALLOUT Cinephilia Review Synopsis: In 1959 Hollywood came to Melbourne in the form of director Stanley Kramer shooting the film adaptation of Neville Shute’s novel, On the Beach, which posits an end of the world scenario in which nuclear war has erupted and Melbourne is waiting for an atomic cloud to travel south and kill the last surviving humans. Fallout is a documentary tracing the story of Shute himself, from his early days in Britain through to his emigration to Australia and the subsequent worldwide response to his novel and the film. Here’s another example of an excellent film picked up by only one local cinema (thank heavens for the Nova!). Fallout works on several interwoven levels – it is at once the story of a famous novelist whose life was filled with fascinating details. It is also a depiction of a more naïve and insular time when a Hollywood movie being made here in Melbourne was the talk of the town, as was the presence of famous stars Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, Antony Perkins and Fred Astaire. And underlying all this is the ominous theme of Shute’s novel which, when talking today about the still-relevant possible annihilation of the human species, is nothing short of compulsory reading for war-mongers everywhere. The director’s artful use of archival footage is impressive flowing along almost seamlessly into the main narrative. The film hits a nerve from the opening scene in which J.F.K. contemplates in a speech the possibility of nuclear annihilation and we then see the iconic image of a billowing exploding A-bomb. -

Beach Nourishment in China: Status and Prospects

BEACH NOURISHMENT IN CHINA: STATUS AND PROSPECTS Feng Cai1, Robert G Dean2, Jianhui Liu1,3 Many beach nourishment projects have been performed in China over the last 2 decades since the first project was completed in 1990 in Hong Kong. The history and distribution of beach nourishment in China is summarized in this paper. Considering the development of nourishment design and public perceptions, the history of beach fill in China can be summarized into 3 stages. In general, this paper shows the characteristics of 4 types of nourishment projects based on different environmental conditions, 4 typical nourished sites for each type were selected and described in detail respectively. Considering the current research status in China, recommendations and suggestions for future development are outlined, including such aspects as construction of more and larger projects, development of beach management strategies, a beach nourishment manual, research efforts on numerical models for sediment transport and post-project monitoring and evaluation. Keywords: beach nourishment; beach design; China 1. INTRODUCTION Beach nourishment comprises the placement of large quantities of good quality sand on the beach to advance it seaward (Dean, 2002). The principal approach to protecting coastal property and maintaining recreational beaches in the United States today is beach nourishment. It also has been applied successfully to beach stabilization and development of beaches where none were present in many countries including the Netherlands, Japan, Spain, Germany, France, etc. China has 18000 km of mainland coastline, about 1/3 of them consist of sandy beaches, and 70% of sandy beaches are experiencing coastal erosion (Xia, 1996). Coastal erosion has become a major concern for future socio-economic developments in coastal cities (Cai et al., 2009).