The Emergence of a Collaborative Approach Challenges Hong Kong's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Translation) Minutes of the 23 Meeting of the 4 Wan Chai District

(Translation) Minutes of the 23rd Meeting of the 4th Wan Chai District Council Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Date: 7 July 2015 (Tuesday) Time: 2:30 p.m. Venue: District Council Conference Room, Wan Chai District Office, 21/F Southorn Centre, 130 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, H.K. Present Chairperson Mr SUEN Kai-cheong, SBS, MH, JP Vice-Chairperson Mr Stephen NG, BBS, MH, JP Members Ms Pamela PECK Ms Yolanda NG, MH Ms Kenny LEE Ms Peggy LEE Mr Ivan WONG, MH Mr David WONG Mr CHENG Ki-kin Dr Anna TANG, BBS, MH Ms Jacqueline CHUNG Dr Jeffrey PONG 1 23 DCMIN Representatives of Core Government Departments Ms Angela LUK, JP District Officer (Wan Chai), Home Affairs Department Ms Renie LAI Assistant District Officer (Wan Chai), Home Affairs Department Ms Daphne CHAN Senior Liaison Officer (Community Affairs), Home Affairs Department Mr CHAN Chung-chi District Environmental Hygiene Superintendent (Wan Chai), Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Mr Nelson CHENG District Commander (Wan Chai), Hong Kong Police Force Ms Dorothy NIEH Police Community Relation Officer (Wan Chai District), Hong Kong Police Force Mr FUNG Ching-kwong Assistant District Social Welfare Officer (Eastern/Wan Chai)1, Social Welfare Department Mr Nelson CHAN Chief Transport Officer/Hong Kong, Transport Department Mr Franklin TSE Senior Engineer 5 (HK Island Div 2), Civil Engineering and Development Department Mr Simon LIU Chief Leisure Manager (Hong Kong East), Leisure and Cultural Services Department Ms Brenda YEUNG District Leisure Manager (Wan Chai), Leisure and -

Hong Kong Final Report

Urban Displacement Project Hong Kong Final Report Meg Heisler, Colleen Monahan, Luke Zhang, and Yuquan Zhou Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Research Questions 5 Outline 5 Key Findings 6 Final Thoughts 7 Introduction 8 Research Questions 8 Outline 8 Background 10 Figure 1: Map of Hong Kong 10 Figure 2: Birthplaces of Hong Kong residents, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 11 Land Governance and Taxation 11 Economic Conditions and Entrenched Inequality 12 Figure 3: Median monthly domestic household income at LSBG level, 2016 13 Figure 4: Median rent to income ratio at LSBG level, 2016 13 Planning Agencies 14 Housing Policy, Types, and Conditions 15 Figure 5: Occupied quarters by type, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Figure 6: Domestic households by housing tenure, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Public Housing 17 Figure 7: Change in public rental housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 18 Private Housing 18 Figure 8: Change in private housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 19 Informal Housing 19 Figure 9: Rooftop housing, subdivided housing and cage housing in Hong Kong 20 The Gentrification Debate 20 Methodology 22 Urban Displacement Project: Hong Kong | 1 Quantitative Analysis 22 Data Sources 22 Table 1: List of Data Sources 22 Typologies 23 Table 2: Typologies, 2001-2016 24 Sensitivity Analysis 24 Figures 10 and 11: 75% and 25% Criteria Thresholds vs. 70% and 30% Thresholds 25 Interviews 25 Quantitative Findings 26 Figure 12: Population change at TPU level, 2001-2016 26 Figure 13: Change in low-income households at TPU Level, 2001-2016 27 Typologies 27 Figure 14: Map of Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Table 3: Table of Draft Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Typology Limitations 29 Interview Findings 30 The Gentrification Debate 30 Land Scarcity 31 Figures 15 and 16: Google Earth Images of Wan Chai, Dec. -

Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM)

Appendix Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM) The Honourable Chief Justice CHEUNG Kui-nung, Andrew Chief Justice CHEUNG is awarded GBM in recognition of his dedicated and distinguished public service to the Judiciary and the Hong Kong community, as well as his tremendous contribution to upholding the rule of law. With his outstanding ability, leadership and experience in the operation of the judicial system, he has made significant contribution to leading the Judiciary to move with the times, adjudicating cases in accordance with the law, safeguarding the interests of the Hong Kong community, and maintaining efficient operation of courts and tribunals at all levels. He has also made exemplary efforts in commanding public confidence in the judicial system of Hong Kong. The Honourable CHENG Yeuk-wah, Teresa, GBS, SC, JP Ms CHENG is awarded GBM in recognition of her dedicated and distinguished public service to the Government and the Hong Kong community, particularly in her capacity as the Secretary for Justice since 2018. With her outstanding ability and strong commitment to Hong Kong’s legal profession, Ms CHENG has led the Department of Justice in performing its various functions and provided comprehensive legal advice to the Chief Executive and the Government. She has also made significant contribution to upholding the rule of law, ensuring a fair and effective administration of justice and protecting public interest, as well as promoting the development of Hong Kong as a centre of arbitration services worldwide and consolidating Hong Kong's status as an international legal hub for dispute resolution services. The Honourable CHOW Chung-kong, GBS, JP Over the years, Mr CHOW has served the community with a distinguished record of public service. -

Branch List English

Telephone Name of Branch Address Fax No. No. Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 2545 0950 Des Voeux Road West Branch 111-119 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2546 1134 2549 5068 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 2855 0240 Happy Valley Branch 11 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 2838 6668 2573 3662 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 2525 8756 409 Hennessy Road Branch 409-415 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2835 6118 2591 6168 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 2545 4896 Wan Chai (China Overseas Building) Branch 139 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2529 0866 2866 1550 Johnston Road Branch 152-158 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2574 8257 2838 4039 Gilman Street Branch 136 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2135 1123 2544 8013 Wyndham Street Branch 1-3 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong 2843 2888 2521 1339 Queen’s Road Central Branch 81-83 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong 2588 1288 2598 1081 First Street Branch 55A First Street, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong 2517 3399 2517 3366 United Centre Branch Shop 1021, United Centre, 95 Queensway, Hong Kong 2861 1889 2861 0828 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2291 6081 2291 6306 Causeway Bay Branch 18 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2572 4273 2573 1233 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 2804 6370 Harbour Road Branch Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, -

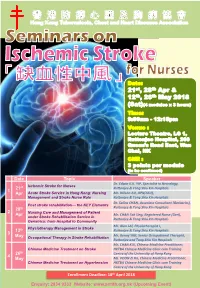

21St, 28Th Apr & 12Th, 26Th May 2018 (Sat)(4 Modules X 3 Hours)

Date: 21st, 28th Apr & 12th, 26th May 2018 (Sat)(4 modules x 3 hours) Time: 9:00am - 12:15pm Venue : Lecture Theatre, LG 1, Ruttonjee Hospital, 266 Queen’s Road East, Wan Chai, HK CNE : 3 points per module (to be confirmed) Date Topic Speaker Dr. Edwin K.K. YIP, Specialist in Neurology, Ischemic Stroke for Nurses 21st Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 1 Apr Acute Stroke Service in Hong Kong: Nursing Mr. Wilson AU, APN(ASU), Management and Stroke Nurse Role Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Dr. Selina CHAN, Associate Consultant (Geriatrics), Post stroke rehabilitation— the KEY Elements 28th Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 2 Nursing Care and Management of Patient Apr Mr. CHAN Tak Sing, Registered Nurse (Geri), under Stroke Rehabilitation Service in Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Geriatrics: from Hospital to Community Mr. Alan LAI, Physiotherapist I, Physiotherapy Management in Stroke 12th Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals 3 Mr. Benny YIM, Senior Occupational Therapist, May Occupational Therapy in Stroke Rehabilitation Ruttonjee and Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals Mr. CHAN KUI, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Chinese Medicine Treatment on Stroke HKTBA Chinese Medicine Clinic cum Training 26th Centre of the University of Hong Kong 4 May Ms. POON Zi Ha, Chinese Medicine Practitioner, Chinese Medicine Treatment on Hypertension HKTBA Chinese Medicine Clinic cum Training Centre of the University of Hong Kong Enrollment Deadline: 18th April 2018 Enquiry: 2834 9333 Website: www.antitb.org.hk (Upcoming Event) Seminars on “Ischemic Stroke” for Nurses Objectives a) To strengthen, update and develop knowledge of nurses on the topic of endocrine system. b) To enhance the skills and technique in daily practice. -

Town Planning Appeal No. 18 of 2005

IN THE TOWN PLANNING APPEAL BOARD Town Planning Appeal No. 18 of 2005 BETWEEN WAN SHUET CHUN (溫雪珍) 1st Appellant CHAN WAI HING (陳惠興) 2nd Appellant LEE YUK PING (李玉萍) 3rd Appellant LAU WING YEE (劉穎而) 4th Appellant TAM KIN YEUNG (譚建陽) 5th Appellant YEUNG YUET YING (JANET) 6th Appellant CHAN TAK MING & TAM KWAN HING 7th Appellant TSANG SIM (曾嬋) 8th Appellant NG MAN SHING (伍萬成) 9th Appellant FOK LAI CHING 10th Appellant FREE WAVE CO. LTD. 11th Appellant RACO INVESTMENT LTD (偉恆昌) 12th Appellant WEI HUA DEVELOPMENT LTD (偉華發展) 13th Appellant IP TAK HING 14th Appellant CHAN NGO & YIP PUI (陳娥 & 葉培) 15th Appellant CHING KANG HOI (程鏡海) 16th Appellant TSE SAI KUI (謝世區) 17th Appellant LEE KIT MAN (李潔雯) 18th Appellant SUEN CHING TONG (孫政堂) 19th Appellant and THE TOWN PLANNING BOARD Respondent Appeal Board : Mr. Patrick FUNG Pak-tung, SC (Chairman) Mr. KAM Man-kit (Member) Ms. Helen KWAN Po-jen (Member) Ms. Ivy TONG May-hing (Member) Mr. WONG Chun-wai (Member) In Attendance : Miss Christine PANG (Secretary) Representation : Mr. TO Lap-kee, Madam FOK Lai-ching & Others as representatives of the Appellants Mr. Simon LAM (instructed by the Department of Justice) for the Respondent Date of Hearing: 1st, 3rd, 14th November & 6th December 2006 Date of Decision: 12th April 2007 D E C I S I O N - 2 - The Constitution of the Appeal Board 1. Before we go into the substance of this Appeal, we need to deal with the constitution of the Appeal Board. 2. As indicated by the formal part of this Decision above, this Appeal was originally heard by five members of the Appeal Board, including Mr. -

1193Rd Minutes

Minutes of 1193rd Meeting of the Town Planning Board held on 17.1.2019 Present Permanent Secretary for Development Chairperson (Planning and Lands) Ms Bernadette H.H. Linn Professor S.C. Wong Vice-chairperson Mr Lincoln L.H. Huang Mr Sunny L.K. Ho Dr F.C. Chan Mr David Y.T. Lui Dr Frankie W.C. Yeung Mr Peter K.T. Yuen Mr Philip S.L. Kan Dr Lawrence W.C. Poon Mr Wilson Y.W. Fung Dr C.H. Hau Mr Alex T.H. Lai Professor T.S. Liu Ms Sandy H.Y. Wong Mr Franklin Yu - 2 - Mr Daniel K.S. Lau Ms Lilian S.K. Law Mr K.W. Leung Professor John C.Y. Ng Chief Traffic Engineer (Hong Kong) Transport Department Mr Eddie S.K. Leung Chief Engineer (Works) Home Affairs Department Mr Martin W.C. Kwan Deputy Director of Environmental Protection (1) Environmental Protection Department Mr. Elvis W.K. Au Assistant Director (Regional 1) Lands Department Mr. Simon S.W. Wang Director of Planning Mr Raymond K.W. Lee Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Ms Jacinta K.C. Woo Absent with Apologies Mr H.W. Cheung Mr Ivan C.S. Fu Mr Stephen H.B. Yau Mr K.K. Cheung Mr Thomas O.S. Ho Dr Lawrence K.C. Li Mr Stephen L.H. Liu Miss Winnie W.M. Ng Mr Stanley T.S. Choi - 3 - Mr L.T. Kwok Dr Jeanne C.Y. Ng Professor Jonathan W.C. Wong Mr Ricky W.Y. Yu In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Ms Fiona S.Y. -

District Profiles 地區概覽

Table 1: Selected Characteristics of District Council Districts, 2016 Highest Second Highest Third Highest Lowest 1. Population Sha Tin District Kwun Tong District Yuen Long District Islands District 659 794 648 541 614 178 156 801 2. Proportion of population of Chinese ethnicity (%) Wong Tai Sin District North District Kwun Tong District Wan Chai District 96.6 96.2 96.1 77.9 3. Proportion of never married population aged 15 and over (%) Central and Western Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District North District District 33.7 32.4 32.2 28.1 4. Median age Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District Sha Tin District Yuen Long District 44.9 44.6 44.2 42.1 5. Proportion of population aged 15 and over having attained post-secondary Central and Western Wan Chai District Eastern District Kwai Tsing District education (%) District 49.5 49.4 38.4 25.3 6. Proportion of persons attending full-time courses in educational Tuen Mun District Sham Shui Po District Tai Po District Yuen Long District institutions in Hong Kong with place of study in same district of residence 74.5 59.2 58.0 45.3 (1) (%) 7. Labour force participation rate (%) Wan Chai District Central and Western Sai Kung District North District District 67.4 65.5 62.8 58.1 8. Median monthly income from main employment of working population Central and Western Wan Chai District Sai Kung District Kwai Tsing District excluding unpaid family workers and foreign domestic helpers (HK$) District 20,800 20,000 18,000 14,000 9. -

Information Paper Food and Environmental Hygiene Committee Paper No.30/2014

2nd September 2014 Wan Chai District Council Information Paper Food and Environmental Hygiene Committee Paper No.30/2014 Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Anti-mosquito Campaign 2014 (Phase III) in Wan Chai District Purpose The purpose of this paper is to brief Members of the details and arrangements for the Anti-mosquito Campaign 2014 (Phase III) to be launched by the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) in Wan Chai District. Background 2. The Anti-mosquito Campaign 2014 (Phase II) organized by FEHD was launched between 28.4.2014 and 4.7.2014. Actions taken in the district and the results are detailed at Annex I . 3. Last year, there were two local, three imported and one unclassified Japanese encephalitis cases, 103 imported dengue fever cases and 5 imported chikungunya fever cases in Hong Kong. On the other hand, one local Japanese encephalitis case had been reported in June this year. In order to safeguard public health and to sustain anti-mosquito efforts, FEHD will continue to strengthen mosquito control and organize the Anti-mosquito Campaign 2014 (Phase III) for eight consecutive weeks from 18.8.2014 to 10.10.2014. 4. The Anti-mosquito Campaign 2014 (Phase III) to be carried out under - 1 - the slogan “ Prevent Japanese Encephalitis and Dengue Fever Act Now! ” aims to achieve the following objectives - (a) To heighten public awareness of the potential risk of dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis, chikungunya fever and other mosquito-borne diseases; (b) To encourage community participation and forge close partnership of government departments concerned in anti-mosquito work; and (c) To eliminate potential mosquito breeding sites . -

Wan Chai Connect Design Group Lead Consultant / Ideation / Buro Happold Multi Disciplinary Engineering / Sustainability Strategy

52 CITIES Wan Chai Connect Design Group Lead Consultant / Ideation / Buro Happold Multi Disciplinary Engineering / Sustainability Strategy Conceptual Architects Urban Design DCMSTUDIOS Architects Conceptual Master Planning Studio B Cost Management Currie and Brown Public Relations Stakeholder Engagement Executive Counsel Real Estate Advisory Knight Frank WAN CHAI Socal Economic Impact Waters Economics BuroHappold marketing and relationships director, Peter Dampier, said: “Serving as a catalyst for regeneration, we hope this sparks serious debate around the provision and ownership of quality public space. Private developers haven’t always historically worked with local communities to create functional but iconic public spaces or looked beyond the site to maximise value.” The Design Group believes that the provision of public space should be considered now in conjunction with the needs and desires of the Wan Chai community. The estimated cost of Wan Chai Connect’s social infrastructure (excluding the extension to the convention centre and new commercial tower) is HK$1.65 Billion. CONNECTS Wan Chai Connect presents a rare, visionary and unmissable opportunity to restore illed as Hong Kong’s equivalent of the New York High Line, Wan Chai Connect is a Hong Kong’s position as a leading World City. vision for the future, weaving old Wan Chai and the harbour, back together. Studio B managing director, Peter Brannan, said: “Taking inspiration from innovative projects B such as New York High Line (an abandoned railway redeveloped into a green walkway Making something out of nothing, Wan Chai Connect is a progressive idea conceptualised to deliver true world-class placemaking, a significant new public space, maximising societal and now the No.1 tourist attraction in New York), Seoul’s Seoullo (a former highway value, connecting the fragmented, and making it safe, enjoyable and smart to walk easily transformed to a sky garden) and Hong Kong Mid-Levels escalators (that has catalysed around Wan Chai. -

Page 1 of Annex a Development Proposals/Cases Related To

Page 1 of Annex A Development Proposals/Cases Related to Preservation of Historic Buildings (Position as at 30 November 2010) Hong Kong Island Development Project/Case Built Heritage At The Site Background & Current Progress 1. Revitalization of the Former Central The CPS Compound comprising the Central Following extensive consultation with the public and Police Station Compound (CPS Police Station, the Central Magistracy and the the local arts and cultural sector, a revised design for Compound) Victoria Prison has been declared a monument the project was announced on 11 October 2010. since 1995. There are a number of Victoria-style buildings within the site. A Conservation Under the revised design, the CPS Compound will be Management Plan (CMP) was presented to the revitalised as a centre for heritage, art and leisure, Board at its meeting on 26 November 2008. complementing the organic development of the neighbouring area as a contemporary arts zone. All 15 historic buildings in the Compound will be preserved. Two new buildings of a modest scale will be constructed, namely the Old Bailey Wing to house gallery space and the Arbuthnot Wing to house a multi-purpose venue as well as central plant. In response to the public views received, the height and the bulk of the proposed new structures have been substantially reduced and the F Hall will be preserved. Accessibility to the compound and connectivity within the compound has been enhanced under the revised design. 2. Re-provisioning of David Trench The Old Upper Levels Police Station, commonly HIA including a CMP has been conducted for the Rehabilitation Centre to the Old known as “No. -

Designated 7-11 Convenience Stores

Store # Area Region in Eng Address in Eng 0001 HK Happy Valley G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0009 HK Quarry Bay Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0028 KLN Mongkok G/F., Comfort Court, 19 Playing Field Rd., Kln 0036 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0077 KLN Kowloon City Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0084 HK Wan Chai G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 HK Sheung Wan G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0094 HK Causeway Bay Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0102 KLN Jordan G/F, 11 Nanking Street, Kln 0119 KLN Jordan G/F, 48-50 Bowring Street, Kln 0132 KLN Mongkok Shop 16, G/F., 60-104 Soy Street, Concord Bldg., Kln 0150 HK Sheung Wan G01 Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Rd C, HK-Macau Ferry Terminal, HK 0151 HK Wan Chai Shop 2, 20 Luard Road, Wanchai, HK 0153 HK Sheung Wan G/F., 88 High Street, HK 0226 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, Cheung King Mansion, 144 Austin Road, Kln 0253 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui East Shop 1, Lower G/F, Hilton Tower, 96 Granville Road, Tsimshatsui East, Kln 0273 HK Central G/F, 89 Caine Road, HK 0281 HK Wan Chai Shop A, G/F, 151 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, HK 0308 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Hart Avenue Plaza, 5-9A Hart Avenue, TST, Kln 0323 HK Wan Chai Portion of shop A, B & C, G/F Sun Tao Bldg, 12-18 Morrison Hill Rd, HK 0325 HK Causeway Bay Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0327 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 7, G/F Star House, 3 Salisbury Road, TST, Kln 0328 HK Wan Chai Shop C, G/F, Siu Fung Building, 9-17 Tin Lok Lane, Wanchai, HK 0339 KLN Kowloon Bay G/F, Shop No.205-207, Phase II Amoy Plaza, 77 Ngau Tau Kok Road, Kln 0351 KLN Kwun Tong Shop 22, 23 & 23A, G/F, Laguna Plaza, Cha Kwo Ling Rd., Kwun Tong, Kln.