Brothers of the Christian Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule and Foundational Documents

Rule and Foundational Documents Frontispiece: facsimile reproduction of a page—chapter 22, “Rules Concern- ing the Good Order and Management of the Institute”—from the Rule of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, the 1718 manuscript preserved in the Rome archives of the Institute. Photo E. Rousset (Jean-Baptiste de La Salle; Icono- graphie, Boulogne: Limet, 1979, plate 52). Rule and Foundational Documents John Baptist de La Salle Translated and edited by Augustine Loes, FSC, and Ronald Isetti Lasallian Publications Christian Brothers Conference Landover, Maryland Lasallian Publications Sponsored by the Regional Conference of Christian Brothers of the United States and Toronto Editorial Board Luke Salm, FSC, Chairman Paul Grass, FSC, Executive Director Daniel Burke, FSC William Mann, FSC Miguel Campos, FSC Donald C. Mouton, FSC Ronald Isetti Joseph Schmidt, FSC Augustine Loes, FSC From the French manuscripts, Pratique du Règlement journalier, Règles communes des Frères des Écoles chrétiennes, Règle du Frère Directeur d’une Maison de l’Institut d’après les manuscrits de 1705, 1713, 1718, et l’édition princeps de 1726 (Cahiers lasalliens 25; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1966); Mémoire sur l’Habit (Cahiers lasalliens 11, 349–54; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1962); Règles que je me suis imposées (Cahiers lasalliens 10, 114–16; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1979). Rule and Foundational Documents is volume 7 of Lasallian Sources: The Complete Works of John Baptist de La Salle Copyright © 2002 by Christian Brothers Conference All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Control Number: 2002101169 ISBN 0-944808-25-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-944808-26-3 (paper) Cover: Portrait of M. -

Lasallian Values in Higher Education.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 6, No

Salm, Luke. “Lasallian Values in Higher Education.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 6, no. 2 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2015). © Luke Salm, FSC, STD. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for- profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. Lasallian Values in Higher Education Luke Salm, FSC, STD1 The topic assigned to these reflections concerns Lasallian values in higher education. To anyone familiar with the history of the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools from its seventeenth century origins to its situation in the world today, there are many reasons why it is timely to take a fresh look at the importance of the [De La Salle] Christian Brothers and their educational tradition in our institutions of higher learning. This discussion comes at a time when the Brothers in our schools at every level, but especially in the tertiary institutions, are no longer as predominant among the faculty and administrators as they once were. In fact, it no longer seems possible to think of many of our schools as Brothers’ schools; it is more accurate perhaps to call them Lasallian schools. For that reason, in our colleges and universities in particular, there are many among the faculty, students, and staff who seem to feel that the contribution of the Brothers and their Lasallian teaching tradition is an institutional asset that ought not to be lost. One guarantee that the tradition will be handed on is the continued presence of the Brothers in the university and their individual and corporate commitment to it. -

Summer/Fall 2015 Newsletter (PDF)

4 1'nner-city scholarship fund A Child. A Chance. A Future. Inner-City Scholarship Fund 1011 First Avenue, Suite 1400 New York, NY 10022 www.innercityscholarshipfund.org inner-city inner-city Newsletter of Inner-City Scholarship Fund | Summer/Fall 2015 Edward Cardinal Egan, Frank Rooney, and Ann Mara CONTENTS SAYING GOODBYE TO GREAT FRIENDS COVER STORY 1,8 This year, Inner-City Scholarship Fund lost million in scholarships were awarded Save the Dates! MESSAGE FROM 2 four great champions of Catholic education: to underprivileged children to attend THE EXECUTIVE His Eminence, Edward Cardinal Egan, James Catholic school in the Archdiocese of The 26th Annual Lawyers Luncheon DIRECTOR B. “Jimmy” Lee, Jr., Ann Mara, and Francis New York. His Eminence was a firm believer Cipriani 42nd Street EVENTS 3 C. “Frank” Rooney, Jr. Throughout their that all children should have access to a Thursday, November 5, 2015 SCHOLARSHIP 4-5 lives, these four outstanding individuals quality education and fought passionately PROGRAMS The 39th Annual Award Dinner made Catholic education a viable option for for them throughout his episcopal career. FAMILY ALBUM 6-7 thousands of underprivileged children in Mandarin Oriental IN THE NEWS 8 New York City. Known as “The First Lady of Football,” New Tuesday, December 14, 2015 York Giants owner Ann Mara passed away VOLUNTEERS 9 On March 10th, over 2,500 guests, at the age of 85. A funeral mass was held at CLASS OF 2015 10-11 including Governor Andrew Cuomo St. Ignatius Loyola Church, the same church Published twice yearly by: and Mayor Bill de Blasio, gathered at where she was baptized and both met and Inner-City Scholarship Fund St. -

Brothers of the Christian Schools United States/Toronto Region

Brothers of the Christian Schools United States/Toronto Region 2010-2011 Statistical Report Christian Brothers Conference Hecker Center, Suite 300 3025 Fourth Street, NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Data as of February 2011 Phone: 202-529-0047 Printed May 2011 Fax: 202-529-0775 2010-2011 Statistical Report U.S./Toronto Region U.S./TORONTO REGION 2010-2011 STATISTICAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW OF ALL U.S./TORONTO MINISTRIES AND OFFICES OVERVIEW OF ALL U.S./TORONTO MINISTRIES AND OFFICES TAB ONE: SCHOOLS TABLES PAGE CATEGORY Table 1. 1-1 Canonical "Ownership" of Schools Table 2. 1-2 Number of Schools By District and Grades Table 3. 1-2 Number of Students by Gender Table 4. 1-3 Number of Co-ed vs. All Boys Schools Table 5. 1-3 Number of Students by Religious Preference Table 6. 1-4 Number of Students in by Ethnic Origin Table 7. 1-5 Financial Aid Given in Schools (PK-12) Table 8. 1-5 Number of Students who Qualify for Free or Reduced Lunch Program (PK-12) Table 9. 1-6 Head of School (PK-12) Table 10. 1-6 Number of Full and Part Time Persons in Administration Table 11. 1-7 Number of Full and Part Time Teachers (PK-12) Table 12. 1-8 Number of Full and Part Time Teachers - Higher Education Table 13. 1-9 Number of Full and Part time Other Professionals Table 14. 1-10 Number of Full and Part time Support Staff Table 15. 1-11 Faculty and Staff by Ethnic Origin Table 16. -

What Is a Capuchin Friar? What Do They Do? Who Are They?

what is a capuchin friar? what do they do? who are they? an introduction to the Exactly 257 years ago before anyone knew Capuchin Friars about capuchin monkeys (so named in 1758), there were Capuchin friars. It was more than 400 years after Capuchin friars came into existence in 1528 that anyone tasted a cup of cappuccino (first served in 1948). As for friar’s, no, they aren’t fryers, but some of them do prefer theirs fried, rather than baked or grilled. The ‘hood’? It’s all in the name. The brotherhood is found in all kinds of neighbourhoods, hoods and all. Even if you have known Capuchin friars for a long time, it wouldn’t be surprising if you found them somewhat mysterious. The Catholic Church has many religious Orders and communities of men. So what makes Capuchins different? Aren’t they Franciscans? And how are they different from Diocesan priests? It can all be confusing even for those well versed in Catholic life. Maybe you can recognize a Capuchin because of the curious, medieval clothing he wears, but you might wonder what makes him tick on the inside. Come to think about it, why do they wear that robe? And you might ask why anyone would want to be a Capuchin friar in this day and age? Is there a point to a bunch of men living together? Why don’t they get married like other people? And then there’s the money thing? Like everyone else they need it, but they take a vow of poverty. -

Courtesy and Protocal

WHAT IS THE PROPER DRESS FORMS OF ADDRESS CODE OF A MASON? In referring to a Member of a Lodge, the A Mason's personal appearance in proper form is "Brother" (in the plural Lodge is normally a mark of his respect for "Brethren"). MASONIC COURTESY AND the Fraternity. PROTOCOL The form used when addressing the The proper attire for attending a Lodge Worshipful Master of a Lodge is Masonic Courtesy or Etiquette refers to meeting is normally a coat and tie and "Worshipful Master". A Past Master is those social graces that Distinguish street shoes. Do not let this prevent you referred to as "Worshipful Brother". It Masonic Fellowship. may be termed a from attending Lodge if you don't have a system of formality, which sets Masonry coat or suit. Wear the most appropriate In Lodge Assembled, each Officer is apart from contemporary customs. clothing you own. addressed by the title "Brother" and the title of the station he occupies. Example: The authority of the Worshipful Master If you are taking part in a Degree or an and proper form when entering or retiring Installation, wear the best clothing that you "Brother Senior Warden". from the Lodge are to be observed. can afford. Others may wear tuxedoes for Improper movement of the Brethren about these and other special events, but that Each Brother on the sidelines is the Lodge room is disrespectful and is not does not require you to rush out and buy addressed as "Brother Smith" or "Brother to be tolerated by the Worshipful Master. one "Unless you can afford it and wish to Kenneth", not just as "Pete" or "Joe". -

Bulletin of Information 1945-1946 Fordham Law School

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Law School Bulletins 1905-2000 Academics 1-1-1945 Bulletin of Information 1945-1946 Fordham Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/bulletins Recommended Citation Fordham Law School, "Bulletin of Information 1945-1946" (1945). Law School Bulletins 1905-2000. Book 40. http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/bulletins/40 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academics at FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law School Bulletins 1905-2000 by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BULLETIN OF FORDHAM UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE SCHOOL OF LAW 1945-1946 302 Broadway New York 7, N. Y. THE SCHOOL OF LAW OF FORDHAM UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCEMENT, 1945-1946 FORDHAM UNIVERSITY 302 Broadway, New York 7, N. Y. INFORMATION The office of the Registrar of the Law School, in Room 1301, 302 Broadway, New York, is open during every business day of the year. Information regarding the requirements of the School for entrance, for degree and for admission to the bar, may be obtained upon applica- tion. For further information, address Registrar of the Law School 302 Broadway New York 7, N. Y. THE SCHOOL OF LAW FORDHAM UNIVERSITY NEW YORK THE FACULTY Academic Year 1945-1946 Reverend Robert I. Gannon, S.J President . Director, City Ha// Division Reverend Matthew J. Fitzsimons, S.J. -

La Salle Academy 2017-2018 Annual U P D A

LA SALLE ACADEMY 2017-2018 ANNUA L UPDATE OUR MISSION The mission of La Salle Academy, a rigorous college-preparatory high school, is to educate students of diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds with special outreach to those most in need. We provide a nurturing environment, which fosters spiritual, moral, intellectual, emotional and physical growth in the Roman Catholic tradition and the Lasallian spirit, as embodied in St. John Baptist de La Salle. We create experiences of community within the school and encourage each student to develop their gifts and talents for their own growth, as well as engage in the caring service of others, through its academic, extra-curricular and spiritual programs. LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD Dear Members of the La Salle Community, As we begin another school year, I wanted to take the opportunity to update the La Salle Community on a few of the things happening at La Salle. At the close of fiscal 2018, we find ourselves in one of the best financial positions the school has ever been in. We have just concluded our fourth consecutive year of significant growth in fund raising with nearly $2.7M and our projections are to exceed that amount again this year. I would like to congratulate our administration and faculty led by Dr. Catherine Guerriero. Over the past year, we have expanded to the third floor in our current building and have added a band room, a Chapel, a special education classroom and a library. In addition, we now have more flagship programs than ever before that wrap around the core academic work of La Salle: La Salle in the City (action-based learning trips), La Salle @2:30 (after-school clubs), La Salle Works (internships), La Salle Partners (several collegiate partnerships including The Cooper Union, NYU, La Salle University and St. -

VOCATION STORY:Friar Julian Zambanini, OFM Conv

VOCATION STORY: Friar Julian Zambanini, OFM Conv. When people ask me about myself, I generally begin by telling them I was born in Brooklyn! But I guess I started thinking about my vocation when I was in 7th grade, when our class was given the assignment to write a paragraph on what we would like to be, with a picture of that occupation. I wrote I wanted to be a, “teaching religious brother.” All I remember was a bit of pleased surprise on the part of the Court Street Franciscan, Sr. Casilda, and my parents. “Of course, he’s only 12 and still may change his mind.” And they were right. At the end of 8th grade, I was offered the opportunity to go to St. Francis Seminary, Staten Island, for 4 years of high school. But fortunately, I received a scholarship to attend a local Catholic High School, V.I. (Vincentian Institute) in Albany NY, a co-educational -- boys and girls the same building but separately taught by the Holy Cross Brothers and the Sisters of Mercy. It was the perfect excuse for not going to the seminary at 13 years old and one of the best decisions I have made. I had a great 4 years: the teachers, my friends, the football and basketball games, the dances … in the Marching Band and 2 Dance Bands …. All this time I stayed in contact with Conventual Franciscan Friars at my parish and at the end, although I still was looking to be a, “teaching brother,” I decided to go to St. -

Directory of Discipline of The

25 DIRECTORY OF DISCIPLINE OF THE CANONS REGULAR OF THE NEW JERUSALEM I. INTRODUCTION: 1. The principal end of the Canons Regular of the New Jerusalem is the sanctification of its members through the perfection of charity (Constitutions 1, 10, 24b, 55, 59, 63). This end is achieved through means of community life, liturgical worship according to the particular law of the institute, ascetic discipline and religious vows. 2. The purpose of this Directory of Discipline (DOD) is to establish a pattern in daily personal and community practices which assist members in striving towards that charity which is the common goal of all. For this reason this Directory constitutes a set of particular laws intended to lead members, and the community as a whole, towards the common goal set forth in the Constitutions. 3. A vocation to the Canons Regular of the New Jerusalem is founded in a voluntary self-abandonment to God through the context of its common life. Deliberate disregard of the Rule, Constitutions or Directory of Discipline contradicts the voluntary desire for sanctification expressed by membership. Thus every one incorporated into the CRNJ’s community life is, by his own free choice, bound to obey the whole of the Rule, Constitutions and DOD in a spirit of Christian perfection (cf. Cons., 60, 61). 4. Voluntary disobedience constitutes a breach of charity which effects the life of the community and the member’s place in it. For this reason disobedience is subject to lawful correction for the good of the member and the community as a whole. 5. -

Lasallian Calendar

October 16, 2016 Pope Francis declares Saint Brother SOLOMON LE CLERCQ LLAASSAALLLLIIAANN CCAALLEENNDDAARR 22001177 General Postulation F.S.C.- Via Aurelia 476 – 00165 Roma JANUARY 2017 1 Sunday - S. Mary, Mother of God - World Day of Peace 2 Monday Sts. Basil the Great and Gregory Nazianzen, bishops , doctors 3 Tuesday The Most Holy Name of Jesus 4 Wednesday Bl. Second Pollo, priest. ex-pupil in Vercelli (Italy) 5 Thursday St. Telesphorus, pope 6 Friday - The Epiphany of the Lord Missionary Childhood Day – 1st Friday of the month 7 Saturday St. Raymond of Peñafort 8 Sunday - The Baptism of Jesus Christ St. Laurence Giustiniani 9 Monday St. Julian 10 Tuesday St. Aldus 11 Wednesday St. Hyginus, pope 12 Thursday St. Modestus 1996: Br. Alpert Motsch declared Venerable 13 Friday St. Hilary of Poitiers, bishop, doctor 14 Saturday St. Felix of Nola 15 Sunday II in Ordinary Time Day of Migrants and Refugees - St. Maurus, abbot 16 Monday St. Marcellus I, pope and martyr 17 Tuesday St. Anthony abbot 18 Wednesday St. Prisca 19 Thursday Sts. Marius and family, martyrs 20 Friday Sts. Fabian, pope and Sebastian, martyrs 21 Saturday St. Agnes, virgin and martyr 22 Sunday III in Ordinary Time St. Vincent Pallotti 23 Monday St. Emerentiana 24 Tuesday St. Francis de Sales, bishop and doctor 25 Wednesday - Vocation Day Conversion of St. Paul 26. Thursday – Sts. Timothy and Titus 1725: Benedict XIII approves the Institute by the Bull “In Apostolicae Dignitatis Solio 1937: Transfer to Rome of the relics of St. JB. de La Salle 27 Friday St. Angela Merici, virgin 28 Saturday St. -

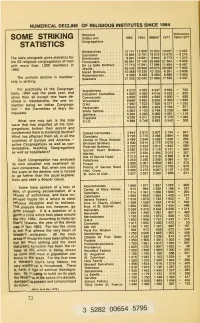

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ...