Prolegomena to the Metaphysics of Tense, the Phenomenology of Temporality, and the Ontology of Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ontotheology? Understanding Heidegger’S Destruktion of Metaphysics* Iain Thomson

T E D U L G O E R · Internationa l Journal o f Philo sophical Studies Vol.8(3), 297–327; · T a p y u lo o r Gr & Fr ancis Ontotheology? Understanding Heidegger’s Destruktion of Metaphysics* Iain Thomson Abstract Heidegger’s Destruktion of the metaphysical tradition leads him to the view that all Western metaphysical systems make foundational claims best understood as ‘ontotheological’. Metaphysics establishes the conceptual parameters of intelligibility by ontologically grounding and theologically legitimating our changing historical sense of what is. By rst elucidating and then problematizing Heidegger’s claim that all Western metaphysics shares this ontotheological structure, I reconstruct the most important components of the original and provocative account of the history of metaphysics that Heidegger gives in support of his idiosyncratic understanding of metaphysics. Arguing that this historical narrative generates the critical force of Heidegger’s larger philosophical project (namely, his attempt to nd a path beyond our own nihilistic Nietzschean age), I conclude by briey showing how Heidegger’s return to the inception of Western metaphysics allows him to uncover two important aspects of Being’s pre-metaphysical phenomeno- logical self-manifestation, aspects which have long been buried beneath the metaphysical tradition but which are crucial to Heidegger’s attempt to move beyond our late-modern, Nietzschean impasse. Keywords: Heidegger; ontotheology; metaphysics; deconstruction; Nietzsche; nihilism Upon hearing the expression ‘ontotheology’, many philosophers start looking for the door. Those who do not may know that it was under the title of this ‘distasteful neologism’ (for which we have Kant to thank)1 that the later Heidegger elaborated his seemingly ruthless critique of Western metaphysics. -

A Critique of the Metaphysics of Presence Peter Eisenman

Lateness: A Critique of the Metaphysics of Presence Peter Eisenman Colin Rowe used to say that one of the problems with architectural thought was that it saw itself in a state of perpetual crisis. Always focusing on the latest problem or issue, architecture was said to obey a crisis mentality, an attitude partly fueled by nostalgia for an impossible avant-garde and partly by the received notion that archi- tecture was actually about solving problems. But as Rowe also would have said, permanent crisis is no crisis at all. For many historians, crisis is part of an historical cycle. In his book Krisis. Saggio sulla crisi del pensiero negativo da Nietzsche a Wittgenstein (1976), the philoso- pher Massimo Cacciari suggests that a crucial change had taken place in the way modernity was perceived. This rupture, he argued, was a "crisis of foundations," which signaled the end of classical rationality and dialectics in philosophy. He suggested that a crisis of dialectical problem of the limit; it projects the crisis of techniques synthesis in fact underlay the history of the modern already given." "The real problem is how to project a phase of contemporary development. Cacciari's crisis of criticism capable of putting itself into crisis by putting dialectical synthesis opens architecture to the synthetic into crisis the real." In his terms, the historical "project" project. In another interpretation, Manfredo Tafuri saw is an open discursive construct. Rather than producing a the idea of crisis as productive. Tafuri considered history linear narrative of history, the crisis provoked by criticism as a project of crisis, in that historical work, i.e. -

Embedding Intentional Semantics Into Inquisitive Semantics Valentin Richard

Embedding Intentional Semantics into Inquisitive Semantics Valentin Richard To cite this version: Valentin Richard. Embedding Intentional Semantics into Inquisitive Semantics. Computation and Language [cs.CL]. 2021. hal-03280889 HAL Id: hal-03280889 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-03280889 Submitted on 7 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Embedding Intentional Semantics into Inquisitive Semantics Valentin D. Richard Master report Université de Paris supervised by Philippe de Groote, Sémagramme team, Loria, Inria Nancy Grand Est, France July 7, 2021 Résumé Plongement de la sémantique intentionnelle en sémantique inquisitrice La sémantique inquisitrice [14] est un modèle de la sémantique de la langue qui représente uniformément les phrases interrogatives et déclaratives. Les propositions sont représentées par un ensemble d’ensembles de mondes possibles, non vide et clos par le bas, dont les élé- ments maximaux sont appelés alternatives. Les questions ont plusieurs alternatives, lesquelles correspondent à leurs réponses possibles. Dans ce mémoire, on examine le plongement de la sémantique intentionnelle dans la sémantique inquisitrice. On conçoit une extension conserva- trice [23] qui à toute représentation sémantique lexicale associe un sens inquisiteur. On prouve que cette transformation conserve la conséquence logique (et donc l’équivalence logique) et la composition. -

Virkelighedsfilosofi Er Jörg Zeller Bogen Er En Del Af Serien Applied Philosophy/ Skrevet Med Henblik På to Målsætninger

Redigeret af Mogens Pahuus Redigeret Redigeret af Mogens Pahuus Jörg Zeller Denne anden del af bogen om virkelighedsfilosofi er Jörg Zeller Bogen er en del af serien Applied Philosophy/ skrevet med henblik på to målsætninger. For det før- Anvendt Filosofi ste skal den gennemføre den i første del opridsede konstruktionsplan for en filosofisk virkelighedsfor- # Filosofiens anvendelighed, 2012 Gunnar Scott Reinbacher & Jörg Zeller ståelse, der tager hensyn til den viden, der præger det begyndende enogtyvende århundrede. For det # Aktuelle etiske udfordringer – bidrag til anvendt etik, 2012 andet skal denne anden del gøre et forsøg på at slå DANNELSE Patrik Kjærsdam Telléus & Mogens Pahuus bro over den kløft mellem to videnskulturer, der er næsten lige så gammel som menneskets refleksion # Praksisformernes etik - bidrag til anvendt etik, 2012 I EN LÆRINGSTID Patrik Kjærsdam Telléus & Mogens Pahuus over grundlaget for og fremgangsmåden i vores vir- kelighedsforståelse – kort sagt: kløften mellem form II Virkelighedsfilosofi DANNELSE I EN LÆRINGSTID DANNELSE # The Challenge of Complexity, 2013 Emnet forog denne indhold artikelsamling. er problemet om dannelsens plads i uddan- Gunnar Scott Reinbacher, Ole Preben Riis & Jörg Zeller nelse og undervisning. Spørgsmålet er, om det er nødvendigt med mere eller S 2.1 S 3.1 mindre explicitte forestillinger om dannelse, forstået som den ønskværdige # Theoretical and Applied Ethics, 2013 udvikling af personligheden hos de, der uddannes og undervises. Man har Hannes Nykänen, Ole Preben Riis, Jörg Zeller formuleret sådanne forestillinger i de sidste 2000 år, men heraf følger ikke, at dannelse fortsat er et gyldigt begreb. Måske er vi nu blevet klogere. Det # Dannelse i en læringstid, 2013 mener faktisk ganske mange i dag, og det er noget af grunden til, at man har S S S S Mogens Pahuus gjort læringsbegrebet til det centrale. -

5 Derrida's Critique of Husserl and the Philosophy

5 DERRIDA’S CRITIQUE OF HUSSERL AND THE PHILOSOPHY OF PRESENCE David B. Allison* Now would be the time to reject the myths of inductivity and of the Wesenschau, which are transmitted, as points of honor, from generation to generation. ...Am I primitively the power to contemplate, a pure look which fixes the things in their temporal and local place and the essences in an invisible heaven; am I this ray of knowing that would have to 1 arise from nowhere? SÍNTESE – O autor reexamina a crítica de Derrida ABSTRACT – The author reexamines Derrida’s à fenomenologia de Husserl de forma a mostrar critique of Husserl’s phenomenology, so as to como a sua coerência estrutural emerge não show how its structural coherency arises not so tanto de uma redução a uma doutrina particular, much from the reduction to a particular doctrine, mas antes das exigências de uma concepção but rather from the demands of a unitary concep- unitária, especificamente impostas pelas deter- tion, specifically from the demands imposed by minações epistemológicas e metafísicas da the epistemological and metaphysical determina- presença. tions of presence. PALAVRAS-CHAVE – Desconstrução. Derrida. KEY WORDS – Deconstruction. Derrida. Husserl. Fenomenologia. Husserl. Presença. Significado. Meaning. Phenomenology. Presence. * Doutor. Professor, State University of New York, Stony Brook, EUA. 1 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l’invisible (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1964), Eng. tr., Alphonso Lingis, The Visible and the Invisible (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1968). pp. 113-116. VERITAS Porto Alegre v. 50 n. 1 Março 2005 p. 89-99 It is practically a truism to say that most of Husserl’s commentators have in- sisted on the rigorously systematic character of his writings. -

Functions: Selection and Mechanisms SYNTHESE LIBRARY

Functions: selection and mechanisms SYNTHESE LIBRARY STUDIES IN EPISTEMOLOGY, LOGIC, METHODOLOGY, AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE Editors-in-Chief: VINCENT F. HENDRICKS, University of Copenhagen, Denmark JOHN SYMONS, University of Texas at El Paso, U.S.A. Honorary Editor: JAAKKO HINTIKKA, Boston University, U.S.A. Editors: DIRK VAN DALEN, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands THEO A.F. KUIPERS, University of Groningen, The Netherlands TEDDY SEIDENFELD, Carnegie Mellon University, U.S.A. PATRICK SUPPES, Stanford University, California, U.S.A. JAN WOLEN´ SKI, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland VOLUME 363 For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/6607 Philippe Huneman Editor Functions: selection and mechanisms Editor Philippe Huneman IHPST (CNRS/Université Paris I Sorbonne) Paris, France ISBN 978-94-007-5303-7 ISBN 978-94-007-5304-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-5304-4 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956316 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, speci fi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on micro fi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied speci fi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

Derrida's Objection to the Metaphysical Tradition

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholarship@Claremont Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2015 Derrida's Objection To The etM aphysical Tradition Christopher A. Wheat Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Wheat, Christopher A., "Derrida's Objection To The eM taphysical Tradition" (2015). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 1188. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1188 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Derrida’s Objection to the Metaphysical Tradition Submitted to Prof. James Kreines And Dean Nicholas Warner By Christopher Wheat For Senior Thesis Spring 2015 4/27/15 Table of Contents: Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………2 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………4 The Metaphysical Tradition…………………………………………………………...6 Derrida’s Objection…………………………………………………………………..16 Metaphysics Given the Abandonment of the Metaphysical Tradition………………26 Conclusion………………………………………………….………………………..31 Bibliography…………………………………………………………..……………..33 1 Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Professor Kreines for his generous assistance in my thesis and initial research of deconstruction, and for helping to nurture my interest in philosophy over the course of my college career. I would also like to thank Professor Rajczi, Professor Schroeder, Professor Kind, Professor Kincaid, and Professor Gaitskill. In addition to my professors, my friends and family have supported and influenced me in ways I could never begin to repay them for, and hope that this thesis is only a small reflection of what they have taught me. 2 Abstract Derrida’s deconstruction of the philosophic tradition shows us not only the importance of pursuit of knowledge, but also the importance of questioning the assumptions on which such a pursuit is based. -

Truth and Simplicity F

Brit. J. Phil. Sci. 58 (2007), 379–386 Truth and Simplicity F. P. Ramsey 1 Preamble ‘Truth and Simplicity’ is the title we have supplied for a very remarkable nine page typescript of a talk that Ramsey gave to the Cambridge Apostles on April 29, 1922.1 It is a relatively early work but it already touches even in such brief compass on several topics of fundamental philosophical interest: truth, ontological simplicity, the theory of types, facts, universals, and probability, that are recurrent themes found in most of Ramsey’s papers, published and posthumous. The present paper has not appeared in any of the classic collections, and it comes as a pleasant surprise—just when we thought we had seen it all.2 In the paper, Ramsey develops two ideas he thinks are related: that ‘true’ is an incomplete symbol, and ‘the only things in whose existence we have reason to believe are simple, not complex’. The first relies on Russell’s notion of an incomplete symbol and the second he says is a view now (1922) held by Russell, and, as he generously says, he got it from Russell in conversation and doubts whether he would ever have thought of it by himself. Ramsey is very clear as to what simplicity requires: I mean that there are no classes, no complex properties or relations, or facts; and that the phrases which appear to stand for these things are incomplete symbols. Ramsey says later in this paper, that the statements that ‘true’ is an incomplete symbol and that everything in the world is simple are part of the same view. -

The Subterranean Influence of Pragmatism on the Vienna Circle: Peirce, Ramsey, Wittgenstein

JOURNAL FOR THE HISTORY OF ANALYTICAL PHILOSOPHY THE SUBTERRANEAN INflUENCE OF PRAGMATISM ON THE VOLUME 4, NUMBER 5 VIENNA CIRCLE: PEIRCE, RAMSEY, WITTGENSTEIN CHERYL MISAK EDITOR IN CHIEF KEVIN C. KLEMENt, UnIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS An underappreciated fact in the history of analytic philoso- EDITORIAL BOARD phy is that American pragmatism had an early and strong in- GaRY EBBS, INDIANA UnIVERSITY BLOOMINGTON fluence on the Vienna Circle. The path of that influence goes GrEG FROSt-ARNOLD, HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES from Charles Peirce to Frank Ramsey to Ludwig Wittgenstein to HENRY JACKMAN, YORK UnIVERSITY Moritz Schlick. That path is traced in this paper, and along the SANDRA LaPOINte, MCMASTER UnIVERSITY way some standard understandings of Ramsey and Wittgen- LyDIA PATTON, VIRGINIA TECH stein, especially, are radically altered. MARCUS ROSSBERG, UnIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT MARK TEXTOR, KING’S COLLEGE LonDON AUDREY YAP, UnIVERSITY OF VICTORIA RICHARD ZACH, UnIVERSITY OF CALGARY REVIEW EDITORS JULIET FLOYD, BOSTON UnIVERSITY CHRIS PINCOCK, OHIO STATE UnIVERSITY ASSISTANT REVIEW EDITOR SEAN MORRIS, METROPOLITAN STATE UnIVERSITY OF DenVER DESIGN DaNIEL HARRIS, HUNTER COLLEGE JHAPONLINE.ORG C 2016 CHERYL MISAK THE SUBTERRANEAN INflUENCE OF saving labor, is . true instrumentally. Satisfactorily . means PRAGMATISM ON THE VIENNA CIRCLE: PEIRCE, more satisfactorily to ourselves, and individuals will emphasize their points of satisfaction differently. To a certain degree, there- RAMSEY, WITTGENSTEIN fore, everything here is plastic. (James 1975, 34–35)2 CHERYL MISAK It was Peirce’s more sophisticated pragmatism that influenced Ramsey. C. K. Ogden, inventor of Basic English, publisher of the Tractaus, and co-author of The Meaning of Meaning, was Ram- sey’s mentor from the time he was a schoolboy. -

Carnap's Logic of Science and Reference to the Present Moment

Carnap's Logic of Science and Reference to the Present Moment Florian Fischer Abstract The important switch from the so-called old B-theory to the new tenseless theory of time (NTT), which had significant implications for the field of tense and indexicals, occurred after Carnap's era. Against this new background, Carnap's original inter-translatability thesis can no longer be upheld. The most natural way out would be to modify Carnap's position according to the NTT; but this is not compatible with Carnap's metaphysi- cal neutrality thesis. Even worse, Carnap's work on measurement theory can be used to develop an argument in favour of the A-theory. I argue that there are tensed basic sentences which are needed in order to construct a tenseless system and thus cannot be translated without loss of meaning into tenseless ones (old B-theory) or made true by tenseless facts (NTT). Keywords: Rudolf Carnap, Philosophy of Time, Tense vs. Tenseless Theory, A-Theory, B-Theory, New Tenseless Theory of Time 1 Carnap and Tense This paper brings the work of Rudolf Carnap together with the modern debate about tense in the philosophy of time. It is an interesting fact that these fields have never been put together,1 despite the fact, or so I believe, that their content is deeply connected. The debate between so-called tensed and tenseless theories is a central issue in contemporary philosophy of time. `Tensers hold that grammatical tense is semantically irreducible, while detensers hold that tense is semantically reducible' [69, p. 2]. Under the buzz phrase `tensed versus tenseless theory', I subsume different philosophical positions about the reference to the present mo- ment. -

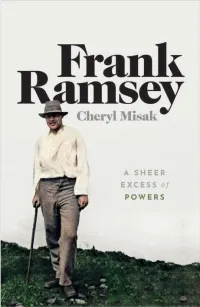

FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi FRANK RAMSEY OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi CHERYL MISAK FRANK RAMSEY a sheer excess of powers 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 7/1/2020, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OXDP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Cheryl Misak The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Forthcoming in Time and Identity: Topics in Contemporary Philosophy

Time and Identity: Topics in Contemporary Philosophy, Vol. 6, Michael O’Rourke, Joseph Campbell, and Harry Silverstein, eds. (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2009). Temporal Reality Lynne Rudder Baker University of Massachusetts Amherst Nonphilosophers, if they think of philosophy at all, wonder why people work in metaphysics. After all, metaphysics, as Auden once said of poetry, makes nothing happen.1 Yet some very intelligent people are driven to spend their lives exploring metaphysical theses. Part of what motivates metaphysicians is the appeal of grizzly puzzles (like the paradox of the heap or the puzzle of the ship of Theseus). But the main reason to work in metaphysics, for me at least, is to understand the shared world that we all encounter and interact with. And the shared world that we all encounter includes us self-conscious beings and our experience. The world that we inhabit is unavoidably a temporal world: the signing of the Declaration of Independence is later than the Lisbon earthquake; the Cold War is in the past; your death is in the future. There is no getting away from time. The ontology of time is currently dominated by two theories: Presentism, according to which “only currently existing objects are real,”2 and Eternalism, according to which “past and future objects and times are just as real as currently existing ones.”3 In my opinion, neither Presentism nor Eternalism yields a satisfactory ontology of time. Presentism seems both implausible on its face and in conflict with the Special Theory of Relativity, and Eternalism gives us no handle on time as universally experienced in terms of an ongoing now.