Integrating Sexual and Reproductive Health in Primary Health Care In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Economy of Belarus Magazine

CONTENTS: FOUNDER: MODERNIZATION Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus MEMBERS: Alexei DAINEKO Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus, Modernization: Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Belarus, Priorities and Essence Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus, Belarusian Telegraph Agency BelTA A country’s prosperity hinges on the pace of its economic modernization 4 EDITORIAL BOARD: Tatyana IVANYUK Mikhail Prime Minister of Belarus, MYASNIKOVICH Corresponding Member of the National Academy Learning of Sciences of Belarus (NASB), Doctor of Economics, from Mistakes Professor (Chairman of the Editorial Board) Total investment spent on the upgrade of Belarus’ wood processing industry Boris BATURA Chairman of the Minsk Oblast is estimated at €801.9 million 9 Executive Committee Olga BELYAVSKAYA Igor VOITOV Chairman of the State Committee for Science and Technology, Doctor of Technical Sciences, A New Lease on Life Professor Belarus is set to upgrade about 3,000 enterprises in 2013 13 Igor VOLOTOVSKY Academic Secretary of the Department of Biological Sciences, NASB, Doctor of Biology, Professor Dmitry ZHUK Director General of Belarusian Telegraph Agency BelTA Vladimir ZINOVSKY Chairman of the National Statistics Committee Alexander Director General of the NASB Powder Metallurgy ILYUSHCHENKO Association, NASB Corresponding Member, Doctor of Technical Sciences, Professor Yekaterina NECHAYEVA Viktor KAMENKOV Chairman of the Supreme Economic Court, Ingredients of Success Doctor of Law, Professor Belarusian companies can rival many world-famous producers 16 Dmitry KATERINICH Industry Minister IN THE SPOTLIGHT Sergei KILIN NASB сhief academic secretary, NASB Corresponding Member, Doctor of Physics and Mathematics, Tatyana POLEZHAI Professor Business Plan Nikolai LUZGIN First Deputy Chairman of the Board of the National for the Country Bank of the Republic of Belarus, Ph.D. -

Health Care System in Belarus: Path of Least Resistance

MODERN ECONOMIC STUDIES, VOLUME 1, ISSUE 1, 2018, pp. 18-27 HEALTH CARE SYSTEM IN BELARUS: PATH OF LEAST RESISTANCE MARIIA CHEBANOVA Kyiv School of Economics KATERYNA CHERNOKNYZHNA Kyiv School of Economics VALENTYNA SINICHENKO1 Kyiv School of Economics ABSTRACT As in other post-Soviet countries, in 1991 the Republic of Belarus started off with a highly centralized Semashko system in healthcare. Over the years of independence, the healthcare system of Belarus has been characterized by great physical and financial access but vast inefficiencies. Using the Harvard flagship approach, we show that there have been no systematic changes in terms of five control knobs of the healthcare system. The relatively minor improvements have concerned anti- alcohol campaigns, improvement of access to healthcare in rural areas, and a shift of primary care to capitation-based financing. As a result, no major improvements of health status have been attained. Key words: healthcare reform, Belarus, Semashko system JEL classifications: H51, I15, P46 1. Overview of the health care system in Belarus 1.1. Principal geographic characteristics and a historical overview According to the Constitution, “the Republic of Belarus is a unitary, democratic, social state based on the rule of law”. The country is situated in Eastern Europe and has a population of approximately 9.5 million people, with less than a quarter living in rural areas. According to the World Bank, Belarus is an upper middle-income country. After the proclamation of independence in 1991, Belarus chose a path of gradual reforms, thereby avoiding a complicated process of economic restructuring; this managed to provide almost a decade of strong economic growth (up to 9% annually) until 2009, when a period of serious turmoil came instead. -

Republic of Belarus: Assessment of the Sustainability of the Opioid Agonist Therapy Programme in the Context of Transition from Donor Support to Domestic Funding

Re p u b l i c o f B e l a r u s : АSSESSMENT OF THE SUSTAINABILITY OF THE OPIOID AGONIST THERAPY PROGRAMME IN THE CONTEXT OF TRANSITION FROM DONOR SUPPORT T O D O M E S T I C F U N D I N G February-April 2020 Aliaksei A. Kralko Acknowledgements This assessment has been initiated by the Eurasian Harm Reduction Association (EHRA) to assess the progress in reaching sustainability of the opioid agonist therapy (OAT) programme in the Republic of Belarus in the context of transition from donor support to domestic funding. The EHRA and the author extend their gratitude for the help in gathering information to the staff members of the state-run institution, “Republican Scientific and Applied Research Centre for Mental Health'; the state-run institution, “Republican Scientific and Applied Research Centre for Medical Technologies, Information, Management and Economics of Health Care”; health care facilities, including the Narcologic Dispensary Clinic of the City of Minsk; the Minsk Regional Clinical Centre 'Psychiatry & Narcology”; the Department of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology of the Belarusian State Medical University; the Department of Psychiatry and Narcology of the Belarusian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education; the Belarusian non-governmental association “Positive Movement”; and the Republican social non-governmental association “Your Chance”. In particular, EHRA and the author are deeply grateful to the member of the Advisory Group for this project whose critical feedback and advice made a significant contribution to the preparation and finalising of this report, namely, Dr. A.A. Alexandrov, Chief Physician of the Minsk Regional Clinical Centre 'Psychiatry & Narcology'; Dr. -

The Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on Public Expenditures on Education and Health in the Economies of the Former Soviet Union

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Chubrik, Alexander; Dabrowski, Marek; Mogilevsky, Roman; Sinitsina, Irina Working Paper The impact of the global financial crisis on public expenditures on education and health in the economies of the former Soviet Union CASE Network Reports, No. 100 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for Social and Economic Research (CASE), Warsaw Suggested Citation: Chubrik, Alexander; Dabrowski, Marek; Mogilevsky, Roman; Sinitsina, Irina (2011) : The impact of the global financial crisis on public expenditures on education and health in the economies of the former Soviet Union, CASE Network Reports, No. 100, ISBN 978-83-7178-549-8, Center for Social and Economic Research (CASE), Warsaw This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/87595 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Prospects for Democracy in Belarus Joerg Forbrig, David R

Demeš (eds.) Demeš Marples Forbrig, Prospects for Democracy in Belarus Joerg Forbrig, David R. Marples and Pavol Demeš, Editors Prospects for Democracy in Belarus in Democracy for Prospects Finland Alyaksandr Mikuláš Dzurinda David J. Kramer Milinkevich Prime Minister of the Deputy Assistant Norway Leader of the United Slovak Republic Secretary for European Democratic Forces in and Eurasian Affairs, Belarus US Department of State Estonia Russia Sweden Our country will never be A free and democratic The story of Belarus the same. We have set in Belarus will be a better and the aspirations motion something that home for its people and of freedom-loving will not be forgotten and for their children. It will Belarusians did not end Latvia cannot be stopped. We be a good neighbor with the March elections. do not know when victory for Europe and Russia On the contrary, it began Denmark will come but we do […] And a free Belarus a new chapter. The Lithuania know that, at some time would send a message weeks, months and even in the future, our victory to the world that the last years ahead may not be is assured. dictatorship in Europe easy. At the same time, has finally come to an change may come sooner end. than many people think. Belarus Either way, we and our European allies remain united on Belarus. Poland Germany Ukraine Czech Republic ISBN 80 - 969487 - 2 - 5 Slovakia Moldova Prospects for Democracy in Belarus Prospects for Democracy in Belarus Joerg Forbrig, David R. Marples and Pavol Demeš Editors 2006 List of Contents Preface Pavol Demeš and Sascha Müller-Kraenner 7 This publication has been supported by the European Commission, within the “Enlargement 200” program as part of the “Neighbourhoods in Europe: Foreword Alyaksandr Milinkevich 9 Within new borders with common perspectives” initiative. -

“Preventing Non-Communicable Diseases, Promoting Healthy Lifestyle and Support to Modernization of the Health System in Belarus” (BELMED)

“Preventing non-communicable diseases, promoting healthy lifestyle and support to modernization of the health system in Belarus” (BELMED) FINAL PROGRAMME1 NARRATIVE REPORT REPORTING PERIOD: 20 NOVEMBER 2015 – 31 AUGUST 2020 Country, Locality(s), Priority Area(s) / Programme Title & Project Number Strategic Results2 ● Programme Title: “Preventing non- Country/Region: communicable diseases, promoting healthy The Republic of Belarus lifestyle and support to modernization of the Priority area/ strategic results: health system in Belarus” Promoting effective prevention of NCDs and ● Programme Number (if applicable): strengthening national health system to ENPI/2014/352-372 effectively address the challenges of NCDs in ● MPTF Office Project Reference Number:3 the Republic of Belarus 00093066 Participating Organization(s) Implementing Partners ● UNDP Ministry of Health ● WHO ● UNICEF ● UNFPA Programme/Project Cost (US$) Programme Duration Total approved budget as per Overall Duration: 57 months, Project document: € 4 100 000 MPTF /JP Contribution4: 11 days ● by Agency (if applicable) Agency Contribution Start Date5 20.11.2015 UNDP, WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA - € 300 000 Government Contribution Original End Date6 (if applicable) 19.11.2019 1 The term “programme” is used for programmes, joint programmes and Projects. 2 Strategic Results, as formulated in the Strategic UN Planning Framework (e.g. UNDAF) or Project document; 3 The MPTF Office Project Reference Number is the same number as the one on the Notification message. It is also referred to as “Project ID” on the Project’s factsheet page the MPTF Office GATEWAY 4 The MPTF or JP Contribution, refers to the amount transferred to the Participating UN Organizations, which is available on the MPTF Office GATEWAY 5 The start date is defined by the date in the signed project document. -

Diabetes in Europe

THE STATE WE ARE IN THE STATE POLICY PUZZLE DIABETES IN EUROPE DIABETES IN DIABETES IN EUROPE – POLICY PUZZLE – THE STATE WE ARE IN COVER_PolicyPuzzle_COVER_PolicyPuzzle_IDF 26/11/14 12:06 Page 1 © European Coalition for Diabetes, 2014 No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the European Coalition for Diabetes. First published, 2005 Second edition, 2008 Third edition, 2011 Fourth edition, 2014 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS POLICY PUZZLE STEERING COMMITTEE • Anne-Marie Felton – Co-Chair of the Policy Puzzle Steering Committee, President of FEND • Michael Hall – Co-Chair of the Policy Puzzle Steering Committee; Medical Doctor, Honorary consultant to the Board of IDF Europe • Clifford Bailey – EURADIA DIAMAP Committee Member, Professor of Clinical Sciences, Aston University, UK • Angus Forbes – FEND, Professor of Clinical Diabetes Nursing at King’s College London, UK • Sarah Hills – Executive Director of EURADIA • Luc Martinez – Liaison Officer of Primary Care Diabetes Europe (PCDE); Professor of General Practice, Pierre et Marie Curie University; Vice-President of the French Society of General Medicine • Tim Nolan – Consultant, Editor of the Policy Puzzle • Michael Skjødt Sørensen – Board Member of IDF Europe; Medical Doctor, Vice-President of the Danish Diabetes Association SENIOR PROJECT RESEARCH STAFF • Elodie Besnier • Mayur Mandalia WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONTRIBUTION OF • Gaël Bassetto – Communication Officer, IDF Europe • Leonor Guariguata – Consultant • Tijana Milanovic – Diabetes Association of Serbia • Lala Rabemananjara – Regional Executive, IDF Europe • Lexitech – Translating • Fastlane – Design and layout • Rosseels – Printing REPORT FUNDING This publication was funded by FEND, IDF Europe, and PCDE, EURADIA provided a donation in kind. -

Report on the Literature Review

Report on the Literature Review Results from the Literature Review concerning “Counteracting brain drain and professional isolation of health professionals in remote primary health care through teleconsultation and telementoring to strengthen social conditions in remote BSR“. Output no. 3.1 Irina Moroz Laura Prett Kaija Loppela, Kristiina Vaahtera, Minna Kamula Bosco Lehr, Katrin Olenik Aigars Miezitis, Madara Vegnere Darius Jegelevičius Anna-Lena Nilsson, Sture Eriksson Output no. 3.1 Output title: Report on transnational literature review Belarus: Irina Moroz Estonia: Laura Prett Finland: Kaija Loppela, Kristiina Vaahtera, Minna Kamula Authors: Germany: Bosco Lehr, Katrin Olenik Latvia: Aigars Miezitis, Madara Vegnere Lithuania: Darius Jegelevičius Sweden: Anna-Lena Nilsson, Sture Eriksson Reviewer: Sami Perälä, South Ostrobothnia Healthtechnology Development Centre (EPTEK) Needs and strategies to counteract brain drain and professional isolation in remote WP title: primary health care through teleconsultation and telementoring Date: 2012.06.25 Page 2 / 105 Output no. 3.1 Output title: Report on transnational literature review Table of Contents Short Abstract ........................................................................................................................ 7 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 2 Methods .................................................................................................................... -

Report on the Assessment of the Actors and Donors Active in the Eastern Partnership Countries in the Field of Local Government

REPORT ON THE ASSESSMENT OF THE ACTORS AND DONORS ACTIVE IN THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP COUNTRIES IN THE FIELD OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT May 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Background ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 3 Common trends and main findings …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Key features of the local government systems in the EaP countries …………………………………………... 9 Instruments of local authorities to promote local economic development ………………………………. 15 Major donors active in the field ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 Annex 1. Country reports on each of the six EaP countries ………………………………………………………. 32 Armenia – Country Report ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 32 Azerbaijan – Country Report ……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 54 Belarus - Country Report …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 67 Georgia – Country Report ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 104 Moldova – Country Report …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 140 Ukraine – Country Report ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 164 2 Introduction This report was drafted during the Inception Phase of the Mayors for Economic Growth (M4EG) Initiative launched by the European Union in October 2016. The report was revised in April-May 2017 based on comments received. The M4EG Initiative targets local authorities throughout the Eastern Partnership Countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine (EaP). The focus of the Initiative is on sustainable local -

Subject Index

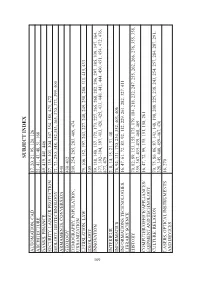

SUBJECT INDEX AUTOMATION, CAD 17, 20, 21, 95, 120, 126 ARCHITECTURE 21, 41, 43, 48, 51, 168 BANKS, FINANCE 49, 419, 441, 446 SECURITY, LABOUR PROTECTION 27, 135, 303, 304, 307, 354, 380, 471, 472 BIOLOGY, BIOTECHNOLOGY 71, 73, 250, 348, 352,353, 365, 370, 373, 399, 400 ARMAMENTS, CONVERSION 440 GEOLOGY 430–432 DEMOGRAPHY, POPULATION, 209, 254, 265, 283, 409, 474 URBANIZATION LEGISLATION, LAW 79, 106, 152, 197, 203, 227, 248, 249, 258, 280, 311, 415, 433 IDEOLOGY 305 109 INNOVATION 59, 138, 140, 157, 172, 173, 227, 265, 268, 282, 296, 297, 305, 339, 347, 364, 377, 392–394, 397, 413, 420, 425, 433, 440, 441, 444, 450, 451, 454, 472, 476, 477, 479 INTERIEUR 2, 8, 14, 15, 21, 31, 48 INFORMATICS 76, 92, 131, 170, 230, 352, 403, 406 INFORMATIONS TECHNOLOGIES, 16, 47, 61, 72, 83, 92, 112, 229, 261, 282, 327, 411 LIBRARY SCIENCE HISTORY 70, 82, 89, 153, 155, 175, 179, 184, 218, 232, 247, 255, 262, 266, 276, 355, 358, 359, 367, 435–439, 468, 469 COMPUTER/OFFICE/APPLIANCES/ 16, 47, 72, 99, 135, 151, 158, 261 EQIPMENT AND TECHNOLOGY CULTURE, RELIGION 70, 75, 80, 86, 87, 143, 148, 198, 208, 225, 238, 243, 254, 257, 284, 287, 291, 328, 345, 408, 459–467, 470 LASERS, OPTICAL INSTRUMENTS 16, 270 AND DEVICES LICHT INDUSTRY 4, 11, 37 FORESTRY, WOODWORKING 22, 43, 407 MASS MEDIA 16, 19, 67, 98 MATHEMATICS AND STATISTICS 56, 57, 96, 211, 230, 297 STUDY OF MATERIALS 74, 109, 161, 162, 165, 346, 381, 387 MACHINERY CONSTRUCTION, 12, 17, 20, 105, 120, 183, 185, 369, 397, 424 MACHINES AND MECHANISMS MEDICINE AND HEALTH 3, 10, 35, 44, 133, 453, 480–569 PROTECTION -

Belarus and the Baltic States: Repercussions of the Lingering Political Crisis Belarus and the Baltic States: Repercussions of the Lingering Political Crisis

The political crisis in Belarus is not yet over. Its continuation risks turning the country into a source of constant challenges for the Baltic states and the EU, as Research report shown by the Ryanair flight incident. BELARUS AND A return to the pre-crisis THE BALTIC STATES: state of relations is impossible without resolution of the Belarusian crisis. New factors have REPERCUSSIONS appeared, including non- recognition of Lukashenka’s legitimacy and Vilnius's OF THE LINGERING hosting of Tsikhanouskaya. POLITICAL CRISIS Although economic Pavel Slunkin, Artyom Shraibman, Hanna Hubarava relations have shown June 2021 resistance to negative political impulses, in the long run the ongoing crisis will inevitably lead to more serious economic repercussions. 1 Research report BELARUS AND THE BALTIC STATES: REPERCUSSIONS OF THE LINGERING POLITICAL CRISIS BELARUS AND THE BALTIC STATES: REPERCUSSIONS OF THE LINGERING POLITICAL CRISIS Index of Contents BELARUS AND THE BALTIC STATES: 4 REPERCUSSIONS OF THE LINGERING POLITICAL CRISIS 1 KEY DRIVERS AND TENDENCIES 5 OF RELATIONS PRIOR TO AND AT THE BEGINNING OF THE CRISIS 2 EFFECTS OF THE POLITICAL CRISIS 7 ON BILATERAL RELATIONS 2.1 Lithuania................................................................................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Latvia ......................................................................................................................................................................... 13 2.3 Estonia ....................................................................................................................................................................