Mobility Master Plan Pedestrian and Bicycle Design Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Basic Roadway Improvements the Street System Provides the Basic Network for Bicycle Travel

Figure 2-1: Many low-volume resi- YES dential streets need only the most basic improve- ments to make them more ridable. 2. Basic Roadway Improvements The street system provides the basic network for bicycle travel. Other ele- ments (e.g., bike lanes and paths) supplement this system. To make most streets work for bicyclists, basic improvements may be needed. Such things as safe railroad crossings, traffic signals that work for bicyclists, and street networks that connect benefit bicyclists and make more bicycle trips possible and likely. 2.1 Roadway types While the most basic improvements are appropriate for all categories of street, some improvements are most appropriate for certain categories. In a typical community, streets types range from quiet residential streets, to minor collector streets, to major arterials, and highways or expressways. Figure 2-2: Long blocks and a lack 2.1.1 Residential streets of connectivity On quiet residential streets with little traffic and slow speeds (fig. 2-1), make trips longer bicyclists and motorists can generally co-exist with little difficulty. Such and discourage streets seldom need bike lanes. Only the most basic improvements may bicycling for pur- poseful trips. be required, for instance: • bicycle-safe drainage grates • proper sight distance at intersections • smooth pavement and proper maintenance One additional factor that may need attention is connectivity. Providing bicycle linkages between residential streets and nearby commercial areas or adjacent neighborhoods can significantly improve bicycling conditions. In many communi- 2-1 Wisconsin Bicycle Facility Design Handbook ties, newer parts of town tend to have dis- Figure 2-3: Bicycle- continuous street networks that require bicy- pedestrian connec- clists, pedestrians, and motorists to travel a tions like that long distance to get to a nearby destination shown can provide (fig. -

Traffic Calming Fact Sheets May 2018 Update Speed Table/Raised Crosswalks

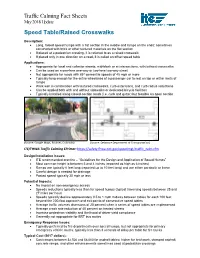

Traffic Calming Fact Sheets May 2018 Update Speed Table/Raised Crosswalks Description: • Long, raised speed humps with a flat section in the middle and ramps on the ends; sometimes constructed with brick or other textured materials on the flat section • If placed at a pedestrian crossing, it is referred to as a raised crosswalk • If placed only in one direction on a road, it is called an offset speed table Applications: • Appropriate for local and collector streets; mid-block or at intersections, with/without crosswalks • Can be used on a one-lane one-way or two-lane two-way street • Not appropriate for roads with 85th percentile speeds of 45 mph or more • Typically long enough for the entire wheelbase of a passenger car to rest on top or within limits of ramps • Work well in combination with textured crosswalks, curb extensions, and curb radius reductions • Can be applied both with and without sidewalks or dedicated bicycle facilities • Typically installed along closed-section roads (i.e. curb and gutter) but feasible on open section (Source: Google Maps, Boulder, Colorado) (Source: Delaware Department of Transportation) ITE/FHWA Traffic Calming EPrimer: https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/speedmgt/traffic_calm.cfm Design/Installation Issues: • ITE recommended practice – “Guidelines for the Design and Application of Speed Humps” • Most common height is between 3 and 4 inches (reported as high as 6 inches) • Ramps are typically 6 feet long (reported up to 10 feet long) and are either parabolic or linear • Careful design is needed for drainage -

Chapter 3 Review Questions

Chapter 3 - Learning to Drive PA Driver’s Manual CHAPTER 3 REVIEW QUESTIONS 1. TEENAGE DRIVERS ARE MORE LIKELY TO BE INVOLVED IN A CRASH WHEN: A. They are driving with their pet as a passenger B. They are driving with adult passengers C. They are driving with teenage passengers D. They are driving without any passengers 2. DRIVERS WHO EAT AND DRINK WHILE DRIVING: A. Have no driving errors B. Have trouble driving slow C. Are better drivers because they are not hungry D. Have trouble controlling their vehicles 3. PREPARING TO SMOKE AND SMOKING WHILE DRIVING: A. Do not affect driving abilities B. Help maintain driver alertness C. Are distracting activities D. Are not distracting activities 4. THE TOP MAJOR CRASH TYPE FOR 16 YEAR OLD DRIVERS IN PENNSYLVANIA IS: A. Single vehicle/run-off-the-road B. Being sideswiped on an interstate C. Driving in reverse on a side street D. Driving on the shoulder of a highway 5. WHEN PASSING A BICYCLIST, YOU SHOULD: A. Blast your horn to alert the bicyclist B. Move as far left as possible C. Remain in the center of the lane D. Put on your four-way flashers 6. WHEN YOU DRIVE THROUGH AN AREA WHERE CHILDREN ARE PLAYING, YOU SHOULD EXPECT THEM: A. To know when it is safe to cross B. To stop at the curb before crossing the street C. To run out in front of you without looking D. Not to cross unless they are with an adult 7. IF YOU ARE DRIVING BEHIND A MOTORCYCLE, YOU MUST: A. -

High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Detection System Testing

High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Detection System Testing Project #: RES2016-05 Final Report Submitted to Tennessee Department of Transportation Principal Investigator (PI) Deo Chimba, PhD., P.E., PTOE. Tennessee State University Phone: 615-963-5430 Email: [email protected] Co-Principal Investigator (Co-PI) Janey Camp, PhD., P.E., GISP, CFM Vanderbilt University Phone: 615-322-6013 Email: [email protected] July 10, 2018 DISCLAIMER This research was funded through the State Research and Planning (SPR) Program by the Tennessee Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration under RES2016-05: High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Detection System Testing. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Tennessee Department of Transportation and the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The State of Tennessee and the United States Government assume no liability of its contents or use thereof. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author(s), who are solely responsible for the facts and accuracy of the material presented. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Tennessee Department of Transportation or the United States Department of Transportation. ii Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. RES2016-05 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date: March 2018 High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Detection System Testing 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Deo Chimba and Janey Camp TDOT PROJECT # RES2016-05 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering; Tennessee State University 11. -

Understanding Intersections –– Stopping at Intersections Are Places Where a Number of Road Users Cross Intersections Paths

4 rules of the road Chapter 3, signs, signals and road markings, gave you some in this chapter information about the most common signs, signals and road markings you will see when driving. This chapter gives • Understanding you the information you’ll need to help you drive safely at intersections intersections, use lanes correctly and park legally. – signalling – types of intersections Understanding intersections – stopping at Intersections are places where a number of road users cross intersections paths. There is often a lot of activity in intersections, so it’s – right‑of‑way at important to be alert. Remember that other road users may be intersections in a hurry, and may want to move into the same space that you • Using lanes are planning on moving into. correctly – which lane Signalling should you use Signals are important — they let other traffic know what you are – lane tracking intending to do. You should signal when you’re preparing to: – turning lanes – reserved lanes • turn left or right – pulling into a • change lanes lane • park – passing – merging • move toward, or away from, the side of the road. – highway or freeway Types of intersections entrances and exits Controlled intersections – cul‑de‑sacs A controlled intersection is one that has signs or traffic lights – turning around telling you what to do. To drive safely in these intersections, you • Parking tips and need to know what the signals and signs mean, and also the rules right‑of‑way rules. But always be cautious. Other drivers may not be paying attention to the signs and signals. Uncontrolled intersections Uncontrolled intersections have no signs or traffic lights. -

Literature Review- Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic

Literature Review Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic July 2018 0 U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. REPORT NO. 2. GOVERNMENT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. FHWA-SA-18-030 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Literature Review: Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic 2018 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR(S) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Bill Schultheiss, Rebecca Sanders, Belinda Judelman, and Jesse Boudart (TDG); REPORT NO. Lauren Blackburn (VHB); Kristen Brookshire, Krista Nordback, and Libby Thomas (HSRC); Dick Van Veen and Mary Embry (MobyCON). 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME & ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NO. Toole Design Group, LLC VHB 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 8300 Boone Boulevard, Suite 300 DTFH61-16-D-00005 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Vienna, VA 22182 12. SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD Federal Highway Administration Office of Safety 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE Washington, DC 20590 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE FHWA 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The Task Order Contracting Officer's Representative (TOCOR) for this task was Tamara Redmon. -

Evaluation of Concrete Pavements with Tied Shoulders Or Widened Lanes Bert E

39 19. K. Y. Kung. A New Method in Correlation Study of vision of Pavements. Proc., 3rd International Con Pavement Deflection and Cracking. Proc., 2nd In ference on Structural Design of Asphalt Pavements, ternational Conference on Structural Design of 1972, pp. 1188-1205. Asphalt Pavements, 1967, pp. 1037-1046. 20. P. H. Leger and P. Autret. The Use of Deflection Publication of this paper sponsored by Committee on Pavement Condi Measurements for the Structural Design and Super- tion Evaluation. Evaluation of Concrete Pavements With Tied Shoulders or Widened Lanes Bert E. Colley, Claire G. Ball, and Pichet Arriyavat, Portland Cement Association Field and laboratory pavements were instrumented and load tested to reducing pavement performance, Because of this prob evaluate the effect of widened lanes, concrete shoulders, and slab thick lem, several states have installed costly longitudinal ness on measured strains and deflectfons. Eight slabs were tested in the and transverse drainage systems. Thus, concrete field and two in the laboratory. Pavement slabs were 203, 229, or 254 shoulders and widened lanes have the potential for curing mm (8, 9, or 10 in) thick. Other major design variables included the width of lane widening, the presence or absence of dowels or of a con many drainage problems as well as providing additional crete shoulder, joint spacing, and the type of shoulder joint construc slab strength. tion. Generally, there was good agreement between measured strains and Many design features contribute to pavement life. values calculated by using Westergaard's theoretical equations. Concrete The effect of some of these features can be evaluated shoulders were effective in reducing the magnitude of measured strains analytically. -

Making Streets Safe

About WalkBoston WalkBoston plays an important role ensuring walker- CHICANE TREES BIKE friendly/safe designs and has an impressive record LANES of getting cities, towns, state agencies, developers, RAISED institutions, and elected officials to provide for the CROSSWALK needs of walkers. Every additional member helps our message be heard. Join online at walkboston.org. We work to transform communities into more walkable CURB places and reintroduce people to walking as a con- EXTENSION venient, healthy and low-cost transportation choice. People who depend on walking most: lower income, elders, children, people with disabilities, and transit PARKED users especially benefit from our advocacy. CARS SPEED How we can help you CUSHION • Advise on walking improvements for your community. MIDBLOCK CROSSWALK • Provide guidance, moral support, technical assistance. making • Give a variety of presentations on pedestrian design and advocacy. Speed Kills: Small-scale fixes go a long way to slow traffic • Help set up advocacy groups and strengthen them. • Demonstrate how these techniques are working streets The human costs and economic consequences of The tools can be small in scale, relatively inexpensive, across Massachusetts and elsewhere. speed-related crashes are immense. In 2007, about and are easily tested and evaluated. Streets can be 31 percent of all fatal crashes were speeding-related, made safer by putting them on a “road diet,” reducing safe resulting in 13,420 fatalities. In Massachusetts, 15 to speeds and enhancing pedestrian safety. Techniques Thanks to our supporters 20 percent of all road fatality victims are pedestrians. include signage, pavement devices and paint. Physically Nationwide, the economic cost to society of speed- or visually narrowing a standard width lane by 1 foot Striders ing-related crashes is estimated to be $40.4 billion slows cars by 7 miles per hour. -

Pedestrian and Bicycle Infrastructure Network Data Catalog

Pedestrian and Bicycle Infrastructure Network Data Catalog Created by Institute for Transportation Research and Education Bicycle and Pedestrian Program For North Carolina Department of Transportation Division of Bicycle and Pedestrian Transportation January 21, 2016 JANUARY 2016 PBIN DATA CATALOG PBIN Data Catalog Each dataset provides a consistent set of attribute fields on existing bicycle, pedestrian, and shared-use path data for use in asset management as well as proposed data for use in planning and project development by PGI awarded communities. Where applicable, fields or attributes marked with an asterisk (*) are required data for NCDOT Planning Grant Initiative (PGI) communities to collect and/or update as a condition of award. PGI communities should consider including additional fields or attributes from the Data Catalog when inventorying focus areas or corridors, as identified through the plan development process. The data catalog is broken up into three sections: 1. BICYCLE ASSETS The Bike_Fac_Linear feature class includes polyline data on existing and proposed facilities such as bike lanes, bike routes, bicycle boulevards, and paved shoulders. It also includes information on surface condition, facility width, slope, and rumble strips. The Bike_Fac_Point feature class includes polyline data on existing and proposed facilities such as bike parking, crossing improvement, bike boxes, bike share kiosks, and bike detection loops. It also includes information on bicycle-oriented signage and hazardous grates. It also includes information on surface condition, facility width, slope, and rumble strips. The Ped_Fac_Linear feature class includes polyline data on existing and proposed facilities such as sidewalks and other types of footpaths. It includes information on material, facility width, buffer, buffer width and slope. -

FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide

BIKEWAY SELECTION GUIDE FEBRUARY 2019 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave Blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED February 2019 Final Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. FUNDING NUMBERS Bikeway Selection Guide NA 6. AUTHORS 5b. CONTRACT NUMBER Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; DTFH61-16-D-00005 Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION VHB, 940 Main Campus Drive, Suite 500 REPORT NUMBER Raleigh, NC 27606 NA Toole Design Group, 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Mobycon - North America, Durham, NC 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AND ADDRESS(ES) AGENCY REPORT NUMBER Tamara Redmon FHWA-SA-18-077 Project Manager, Office of Safety Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE Washington DC 20590 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE This document is available to the public on the FHWA website at: NA https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike 13. ABSTRACT This document is a resource to help transportation practitioners consider and make informed decisions about trade- offs relating to the selection of bikeway types. This report highlights linkages between the bikeway selection process and the transportation planning process. This guide presents these factors and considerations in a practical process- oriented way. It draws on research where available and emphasizes engineering judgment, design flexibility, documentation, and experimentation. 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES Bike, bicycle, bikeway, multimodal, networks, 52 active transportation, low stress networks 16. PRICE CODE NA 17. SECURITY 18. SECURITY 19. SECURITY 20. -

Chapter Four Pedestrian Facility Recommendations

CHAPTER FOUR PEDESTRIAN FACILITY RECOMMENDATIONS This chapter recommends two types of Recommendations included in this chapter are infrastructure improvements: planning-level design concepts. This means that the recommendations are guided by the »» Design concepts for six example plan goals and informed by existing conditions, locations; and prioritized missing best practices, and opportunities identified sidewalk links in the City. The during field work. Additional engineering example location recommendations analysis and field work is needed before show how a mix of treatments can proceeding with project implementation. improve the pedestrian network in a defined area. Recommended Example Locations treatments include sidewalks, pedestrian crossing facilities, and bus Six locations were identified for field work in stop improvements. order to develop conceptual recommendations »» A prioritized list of sidewalk projects. to improve pedestrian safety and comfort. Sidewalk projects are scored and These “example locations” were identified from ranked using the new method several sources, including the demand and recommended in Chapter 3. needs analysis, public input, and input from the City’s technical team. Appendix C provides 76 DECEMBER 2012 sample comments from CommunityWalk of the design concepts are described in around each example location. Chapter 3, Best Practices, Design Standards and Sidewalks. Overall, recommended design The example locations are typical of pedestrian concepts are intended to achieve one or more of conditions in many areas of the City. Thus, the following objectives: these design concepts recommended can be applied elsewhere in the City. The example locations are not in any priority order. Many Ensure ADA compliance. Ensure sufficient crossing time. All sidewalks and intersection features meet Adjust signal timing to ensure pedestrians have at standards set by PROWAAG, NCDOT and the City of least 3.5 feet per second to cross the street. -

Indiana Drivers Manual: Ch. 7

CHAPTER 7 | Safe Vehicle Operation CHAPTER SEVEN | SAFE VEHICLE OPERATION Even the most experienced drivers can be distracted while driving. A defensive driver looks out for the actions of other drivers and anticipates potential problems. LANE MARKINGS Lane markings separate traffic and alert drivers when it is permissible to pass other vehicles. Yellow Lane Markings Yellow lane markings separate multiple lanes of traffic going in opposite directions. You may cross a broken yellow line to pass another vehicle when it is safe, but you should not cross a solid yellow line except to turn. Two-lane road with a solid yellow line Two-lane road with a broken Four-lane road with a solid yellow line yellow line White Lane Markings White lane markings separate multiple lanes of traffic going in the same direction. Most roads with more than two lanes have broken white lines to separate the lanes. You may cross a broken white line when it is safe to change lanes, but you should not cross a solid white line. Three lanes of traffic with broken white lines CHANGING LANES AND PASSING OTHER VEHICLES Change only one lane at a time. When changing lanes to prepare for a turn, you must signal your intention to do so at least 200 feet prior to changing lanes or turning. Your signal distance must be at least 300 feet before the turn if you are operating a vehicle in a speed zone of at least 50 miles per hour. Do not weave in and out of lanes, which will greatly increase your risk of an accident.