A Legal Analysis on the State of Land Evictions in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uoteammemberhandbook2011.Pdf

3 WELCOME! Welcome to Universal Orlando® Resort! You are now a member of an extraordinary team of people whose combined talents make us one of the finest entertainment companies in the world — and a destination that people around the globe desire to visit. We are proud of our accomplishments and are always striving toward our vision of being recognized as the number one entertainment destination in the world! We have developed the most exciting and technologically advanced attractions, we operate the finest shops and restaurants, and we present the most spectacular live entertainment available. Now you are the one who will energize it all… you are the one who will bring it all to life… you are the one who will provide an unforgettably great experience for our guests. Every member of our team is vital to the success of our resort. The friendliness, enthusiasm, and hospitality you extend each day to our guests and each other are critical to our success. You are about to create experiences and thrills that our guests will always remember. This handbook will help you: • learn about our organization; • understand your responsibilities as a Team Member; and • know some of our important policies and procedures. As you learn, please be active and involved. Think about how each idea and each guideline will help us work together to achieve our vision. On behalf of the Universal family, we are proud to welcome you as a new Team Member and to wish you success. We’re glad you’re here! The Team Table of Contents History in the Making ...................................................... -

“Dragon Quest: the Real” Unveil of Detailed Information About the Attraction Three Reasons Why You Can Become a Real Hero

2017 goes beyond “over-the-top” The curtain finally rises on a year that will break through barriers and take you beyond the “over-the-top” 15th anniversary You’re the hero now! “Dragon Quest: The Real” Unveil of detailed information about the attraction Three reasons why you can become a real hero in well-loved world of adventure Open for a limited time only: March 17, 2017 (Fri) to September 3, 2017 (Sun) In 2017, Universal Studios Japan is set to outdo its “over-the-top” 15th anniversary with the new theme of “going beyond ‘over-the-top’!” From March 17 (Fri), USJ will bring you a variety of attractions and pieces of entertainment that go one step beyond. We’d like to share some detailed information about the first installment of this new series of attractions: Dragon Quest: The Real. After its announcement in December of last year, social networking services like Twitter exploded with posts in anticipation, like “What, a tie-in between Universal Studios Japan and Dragon Quest!? I’ve got to go!”, “This is what I’ve been waiting for!”, and “Now I can finally be a hero!”, and there were many posts from people waiting for follow-up information with bated breath as well, such as “I want to know more!” and “I’ve got to get my vacation plans ready when the details come out!”. Please look forward to this emotional experience where you can become a hero and engage in real combat, all in a world of adventure that, so far, you’ve only seen in the games. -

JAPAN "GOLDEN ROUTE" (8) DAYS TOUR (Visit : Osaka Universal St Udios, Nara, Kyot O, Toyohashi, Mt

JAPAN "GOLDEN ROUTE" (8) DAYS TOUR (Visit : Osaka Universal St udios, Nara, Kyot o, Toyohashi, Mt . Fuji, Hakone, Tokyo Disney Resort ) Itinerary: DAY 01 MANILA / OSAKA (D.) Assemble at the airport for your departure flight to OSAKA, JAPAN. Upon arrival at the Kansai Int ernat ional Airport , meet by English speaking guide and transfer for dinner and overnight stay at Nikko Kansai Airport Hot el or similar class. DAY 02 OSAKA UNIVERSAL STUDIOS (B.D.) Breakfast at the hotel. Today begin with full day tour of ?Universal St udios Japan?. It is the legendary entertainment company?s first studio theme park outside of the United States. It combine the most popular rides and shows from Universal?s Hollywood and Florida Movie Studio Theme Parks, along with all new attractions designed specifically for Japan. It features eight areas full of breathtaking and gripping rides and attractions namely : Hollywood with Shrek?s 4- D Adventure,New York with U n i v ersal Studios Japan Terminator 2: 3-D and Amazing Amazing Adventure of Spider Man ? The Ride. San Francisco with Back to the Future ? The Ride and Backdraft, Jurassic Park ? The Ride, Amity Village with Jaws, Water world, Universal Wonderland with three massive areas themed after Sesame Street, Hello Kitty, Peanuts and the newest attraction : The Wizarding World of Harry Potter (expect long queue). Lunch at own arrangement. Buffet dinner at Universal Port or similar. Overnight stay at Hilt on Osaka Hot el or similar class. DAY 03 OSAKA / NARA SIGHTSEEING / OSAKA (B.L.) Breakfast at the hotel. Morning transfer to Nara, which was the Ancient Capital in 710. -

List of Intamin Rides

List of Intamin rides This is a list of Intamin amusement rides. Some were supplied by, but not manufactured by, Intamin.[note 1] Contents List of roller coasters List of other attractions Drop towers Ferris wheels Flume rides Freefall rides Observation towers River rapids rides Shoot the chute rides Other rides See also Notes References External links List of roller coasters As of 2019, Intamin has built 163roller coasters around the world.[1] Name Model Park Country Opened Status Ref Family Granite Park United [2] Unknown Unknown Removed Formerly Lightning Bolt Coaster MGM Grand Adventures States 1993 to 2000 [3] Wilderness Run Children's United Cedar Point 1979 Operating [4] Formerly Jr. Gemini Coaster States Wooden United American Eagle Six Flags Great America 1981 Operating [5] Coaster States Montaña Rusa Children's Parque de la Ciudad 1982 Closed [6] Infantil Coaster Argentina Sitting Vertigorama Parque de la Ciudad 1983 Closed [7] Coaster Argentina Super Montaña Children's Parque de la Ciudad 1983 Removed [8] Rusa Infantil Coaster Argentina Bob Swiss Bob Efteling 1985 Operating [9] Netherlands Disaster Transport United Formerly Avalanche Swiss Bob Cedar Point 1985 Removed [10] States Run La Vibora 1986 Formerly Avalanche Six Flags Over Texas United [11] Swiss Bob 1984 to Operating Formerly Sarajevo Six Flags Magic Mountain States [12] 1985 Bobsleds Woodstock Express Formerly Runaway Reptar 1987 Children's California's Great America United [13] Formerly Green Smile 1984 to Operating Coaster Splashtown Water Park States [14] Mine -

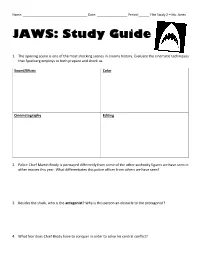

JAWS: Study Guide

Name: ____________________________________ Date: _________________ Period:______ Film Study 2 – Ms. Jones JAWS: Study Guide 1. The opening scene is one of the most shocking scenes in cinema history. Evaluate the cinematic techniques that Spielberg employs to both prepare and shock us. Sound/Music Color Cinematography Editing 2. Police Chief Martin Brody is portrayed differently from some of the other authority figures we have seen in other movies this year. What differentiates this police officer from others we have seen? 3. Besides the shark, who is the antagonist? Why is this person an obstacle to the protagonist? 4. What fear does Chief Brody have to conquer in order to solve his central conflict? 5. Quint and Hooper compare scars to size up their masculinity. In doing so, they bond together. What about this act defines what it means to be a man to these men? 6. Quint’s recounting of the U.S.S. Indianapolis is true. Research it online. When you hear Quint recount this story, does your opinion of him change? Why or why not? Is he still a stereotypical fisherman, a revenge- seeking lunatic, or someone else? Explain. 7. Why does Quint break the radio, preventing them from being able to communicate with anyone? 8. Certainly, the central conflict of Jaws is man vs. nature. Explain how man vs. self and man vs. man are evident in this movie, too. Man vs. Nature Man vs. Self Man vs. Man Discussion Questions 1. One of the themes of Jaws is “Materialistic consumption (i.e. money) shouldn’t drive one’s life.” Explain how the people of Amity Island forget that money isn’t everything. -

Universal Studios Japan® the Park at Halloween Offers a Succession Of

Universal Studios Japan® The Park at Halloween offers a succession of spectacles! Awaken your instincts with this autumn's hottest entertainment “Universal Surprise Halloween” From Friday 9/14/12 to Sunday 11/11/12 Go crazy in the daytime for our photogenic world carnival, "Parade De Carnivale" In the nighttime, our "Halloween Horror Night" brings you the world's most horrific screams with the combination of Resident Evil, Jason and The Mummy! Let your emotions run wild with our daytime and nighttime ultimate experiences! Trick or Treating is enjoyed the world over: Experience it alongside our adorable characters in our family friendly "Universal Wonderland" together with your children to see their maximum smiles! June 29(Fri),2012 Universal Studios Japan will hold the limited seasonal autumn event "Universal Surprise Halloween" from Friday 9/14/12 until Sunday 11/11/12, offering two completely different daytime and nighttime horrifying and impressive experiences. In this Halloween event, you can stay from morning to night to immerse yourself in two completely different worlds. In the daytime, experience the frenzied "Parade De Carnivale", inspired by the world's most traditional festivals. At night, the Park transforms into the "world's scariest" horror experience to bring you "Halloween Horror Night", including the world-shaking Resident Evil, Jason and The Mummy. Not only will the wild parade make you "be surprised", "shout" and "make merry", by exposing you to the thrilling experience of the "fear", "loud screams" and "running away" provided by the "scariest" horror environment, the stress and feelings you work so hard to suppress every day will simply fly away. -

JAWS: a Framework for High-Performance Web Servers

JAWS: A Framework for High-performance Web Servers James C. Hu Douglas C. Schmidt [email protected] [email protected] Department of Computer Science Washington University St. Louis, MO 63130 Abstract Siemens [1] and Kodak [2] and database search engines such as AltaVista and Lexis-Nexis. Developers of communication software face many challenges. To keep pace with increasing demand, it is essential to de- Communication software contains both inherent complexities, velop high-performance Web servers. However, developers such as fault detection and recovery, and accidental complex- face a remarkably rich set of design strategies when config- ities, such as the continuous re-rediscovery and re-invention uring and optimizing Web servers. For instance, developers of key concepts and components. Meeting these challenges must select from among a wide range of concurrency mod- requires a thorough understanding of object-oriented appli- els (such as Thread-per-Request vs. Thread Pool), dispatching cation frameworks and patterns. This paper illustrates how models (such as synchronous vs. asynchronous dispatching), we have applied frameworks and patterns for communication file caching models (such as LRU vs. LFU), and protocol pro- software to develop a high-performance Web server called cessing models (such as HTTP/1.0 vs. HTTP/1.1). No sin- JAWS. gle configuration is optimal for all hardware/software platform JAWS is an object-oriented framework that supports the and workloads [1, 3]. configuration of various Web server strategies, such as a The existence of all these alternative strategies ensures that Thread Pool concurrency model with asynchronous I/O and Web servers can be tailored to their users’ needs. -

JAWS® for Windows® Quick Start Guide

JAWS® for Windows® Quick Start Guide Freedom Scientific, Inc. PUBLISHED BY Freedom Scientific www.FreedomScientific.com Information in this document is subject to change without notice. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or any means electronic or mechanical, for any purpose, without the express written permission of Freedom Scientific. Copyright © 2018 Freedom Scientific, Inc. All Rights Reserved. JAWS is a registered trademark of Freedom Scientific, Inc. in the United States and other countries. Microsoft, Windows 10, Windows 8.1, Windows 7, and Windows Server are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. Sentinel® is a registered trademark of SafeNet, Inc. ii Table of Contents Welcome to JAWS for Windows ................................................................. 1 System Requirements ............................................................................... 2 Installing JAWS ............................................................................................ 3 Activating JAWS ....................................................................................... 3 Dongle Authorization ................................................................................. 4 Network JAWS .......................................................................................... 5 Running JAWS Startup Wizard ................................................................. 5 Installing Vocalizer Expressive Voices ..................................................... -

Towers Thrill Rides Giant Wheels/Round Rides

THRILL RIDES TOWERS GIANT WHEELS/ROUND RIDES SIMULATORS/DARK RIDES GYRO DROP GYRO DROP GYRO DROP GYRO DROP GIANT DROP/GYRO TOWER COMBI SUPER GYRO TOWER 1000 SUPER GYRO TOWER 1200 SUPER GYRO TOWER 1500 GIANT WHEEL STAR WHEEL COASTER WHEEL GIANT WHEEL ON BUILDING BACK TO THE FUTURE HANNA BARBERA MAXI MOTION SEAT 2 MAXI MOTION SEAT 4 T.H.C.: 400–1200 pph T.H.C.: 1000–1680 pph T.H.C.: 1000 pph Stand up vehicle Two in One: white-knuckle rides T.H.C.: 1000pph T.H.C.: 1200pph T.H.C.: 1500pph T.H.C.: 1200–4030 pph T.H.C.: 960–1400 pph T.H.C.: 1000pph T.H.C.: 640 pph Customised Simulator Themed Motion Platform Pavillon de la Vienne Futuroscope T.H.C.: 300–2200pph Height: 54–93 m (177–305 ft) Heights: 54–100 m (177–300 ft) Height: 80 m (262 ft) Stand up & tilt vehicle with great panoramic views. Cabin capacity: 50–60 pers. Cabin capacity: 60–80 pers. Cabin capacity: 90–100 pers. Height: up to 212 m (696 ft) Height: up to 142 m (466 ft) Height: 48 m (157ft) Height: 78 m (246 ft) Capacity per motion-seat: 4 pers. Capacity of ring: 12/20/56 pers. Capacity of ring: 40/60 pers. Capacity of ring: 30 pers. Sit down & tilt vehicle Height: up to 67 m (220 ft) Height: up to 110 m (361 ft) Height: up to 120 m (400 ft) Number of gondolas: up to 90 Number of gondolas: 24/32/40 No. -

Run-On and Fragment Exercise

RUN-ON AND FRAGMENT EXERCISE Below are examples of the four most common kinds of sentence errors, with an abbreviation next to each. In the practice exercises that follow, write the abbreviation that describes each numbered group of words in the space to its left. S = sentence Since he was feeling hungry, John cooked dinner. F = fragment Since he was feeling hungry. CS = comma splice John was feeling hungry, he cooked dinner. FS = fused sentence John was feeling hungry he cooked dinner ___1. One of the most popular films of all time being King Kong a film about a giant gorilla. ___2. Protests against immorality which became very strong by 1928. ___3. Americans will pay to cry the proverbial buckets, too, witness the success of a tear-jerker like Love Story. ___4. Movements toward censorship and federal regulations began. ___5. In the 1970's a new kind of spectacular became popular it allowed the public to have an almost real experience with disaster. ___6. In 1930 the movie industry adopted the Production Code, which probably saved the industry from government control. ___ 7. Then there are the ever-popular Disney cartoons. ___ 8. Since the industry agreed to control itself from within. ___ 9. Some films like Earthquake and Midway which treated the audience to the sights and sounds -- and the sensations of disaster. ___10. In essence the code states that movies may portray immoral conduct but may not advocate it. ___11. Jaws, an unusually frightening film about a shark's attacking swimmers at a popular beach area. ___12. War may not seem a likely booster for the film industry. -

King Kong Project Universal Studios Tour's Most Costly by Linda Deckard

From www.thestudiotour.com All rights reserved AMUSEMENT BUSINESS The International Mass Entertainment Newsweekly April 12 1986 King Kong project Universal Studios Tour's most costly by Linda Deckard The opening of the $6.5million King Kong attraction at Universal Studios Tour here in June will help "establish new plateaus," according to Steve Lew, president of the tour, which is owned and operated by MCA Inc. "King Kong will do what Jaws did in the mid-Seventies, which was to make us a maJor outdoor attraction," said Lew. Interviewed at his office here, Lew is bullish on 1986, coming off a record 1985. "We're more dependent on the world economy, the price of oil and the price of airline fares than most theme parks. We are definitely excited about the rest of the year." The King Kong project, which will occupy a 160 by 160-foot stage and will be part of the tram-ride portion of the tour, represents the largest single-attraction investment yet for MCA. "Conan," a stage show opened in 1983, represented the next highest investment at $5 million. Kong is touted as "the world's largest computerized creature" at 30 feet tall. The King Kong adventure will involve a ride through a devastated New York street, complete with news media broadcasts and screaming victims, climaxed by Kong's sudden appearance three feet from the tram. Guests will have the illusion King Kong is tilting the tram, but they'll be able to escape. The goal of the two-and-a-half minute show is to lure local attendance, particularly repeat visits from those who haven't been to the tour for a year or more. -

Calling Card: 800-657-4711 • ABA Visa® Credit Card • ABA Entertainment Discounts: 301-865-1776

July 1998 Issue 104 © sm American Boating Association • 16 Bank Street • Harwich Port, MA 02646 Boating Safety Summer Thunder Storms Beyond a certain age, portable AM-FM radios and nothing stops fun on the cellular telephones, you’re water better than unex- only a moment away from pected soakings, suddenly everything you should ever violent waves, or any need to know. activity that can lead to a And that’s not all. For serious risk of falling out of the technology-deficient, the boat. And few events toy-deprived or electroni- can end a good time on the cally unprepared, there is water as precipitously as another reliable resource in being hit by lightning. the form of accumulated These are all summer- lore and common sense. time risks, but they can vary greatly in degree of Since thunderstorms usually travel from west to probability depending on your knowledge of - and east, boaters should keep an eye on the western sky. respect for - the weather. Calm usually does precede a storm, so can a There may have been a time, way back before mackerel sky. And yes, red skies at morning are a Odysseus, when ignorance of the elements was an sailor’s warning. excuse for mishap or disaster. But incredible If you don’t have a phone, can’t hear the modern-day refinements in satellite-based forecast- crackling on the AM radio and there is haze in the ing and communications technology have removed path of the roiling clouds, one of the best indicators the last traces of an alibi for being caught on the of increased electrical activity in the area is still the water unawares.