1002915 [2011] RRTA 615 (14 July 2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Govt Works with Private Sector on Deadly Virus

WEDNESDAY MARCH 18, 2020 l 16 PAGES l ISSUE 5 VOL 11 l WWW.FIJI.GOV.FJ Fijijj Focus Govt works with private sector on deadly virus Attorney-General and Minister for Economy Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum and Minister for Industry, Trade, Tourism, Local Government, Housing and Community Development Premila Kumar during the open discussion on the impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) on businesses. Photo: AZARIA FAREEN COVID-19 WATCH AZARIA FAREEN World Health Organization especially with day as many times you like and this in fact gestions that will drive the businesses and the phenomenal statistics coming out from is a creative way of having money coming that in turn will drive our economy,” she USINESS leaders, policy makers different countries.” in the country which would help business- said. and member of the Fiji Chamber The A-G said the Government is open to es meet their cash-flow and continue with “It is better for the Ministry of Economy BOf Commerce and Industry met this assist and look at some form of subsidi- their mortgage payments among others,” to receive submissions that are more mean- week for an open discussion on the impact zation for business sectors which will be the A-G added. ingful for the specific sector then to receive of Coronavirus (COVID-19) on businesses directly impacted upon that has enormous A number of recommendations was put submissions which are very broad and gen- in Fiji. ramification upon the country’s economic forward from the various business sectors eral. Speaking during a panel discussion, Min- growth and foreign reserves. -

CONSTITUTION of the REPUBLIC of FIJI CONSTITUTION of the REPUBLIC of FIJI I

CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI i CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI CONTENTS _______ PREAMBLE CHAPTER 1—THE STATE 1. The Republic of Fiji 2. Supremacy of the Constitution 3. Principles of constitutional interpretation 4. Secular State 5. Citizenship CHAPTER 2—BILL OF RIGHTS 6. Application 7. Interpretation of this Chapter 8. Right to life 9. Right to personal liberty 11. Freedom from cruel and degrading treatment 12. Freedom from unreasonable search and seizure 13. Rights of arrested and detained persons 14. Rights of accused persons 15. Access to courts or tribunals 16. Executive and administrative justice 17. Freedom of speech, expression and publication 18. Freedom of assembly 19. Freedom of association 20. Employment relations 21. Freedom of movement and residence 22. Freedom of religion, conscience and belief 23. Political rights 24. Right to privacy 25. Access to information 26. Right to equality and freedom from discrimination 27. Freedom from compulsory or arbitrary acquisition of property 28. Rights of ownership and protection of iTaukei, Rotuman and Banaban lands 29. Protection of ownership and interests in land 30. Right of landowners to fair share of royalties for extraction of minerals 31. Right to education 32. Right to economic participation 33. ii 34. Right to reasonable access to transportation 35. Right to housing and sanitation 36. Right to adequate food and water 37. Right to social security schemes 38. Right to health 39. Freedom from arbitrary evictions 40. Environmental rights 41. Rights of children 42. Rights of persons with disabilities 43. Limitation of rights under states of emergency 44. -

Fiji's Constitution of 2013

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:28 constituteproject.org Fiji's Constitution of 2013 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:28 Table of contents Preamble . 8 CHAPTER 1: THE STATE . 8 1. The Republic of Fiji . 8 2. Supremacy of the Constitution . 9 3. Principles of constitutional interpretation . 9 4. Secular State . 9 5. Citizenship . 10 CHAPTER 2: BILL OF RIGHTS . 11 6. Application . 11 7. Interpretation of this Chapter . 11 8. Right to life . 12 9. Right to personal liberty . 12 10. Freedom from slavery, servitude, forced labour and human trafficking . 13 11. Freedom from cruel and degrading treatment . 14 12. Freedom from unreasonable search and seizure . 14 13. Rights of arrested and detained persons . 14 14. Rights of accused persons . 15 15. Access to courts or tribunals . 17 16. Executive and administrative justice . 18 17. Freedom of speech, expression and publication . 18 18. Freedom of assembly . 19 19. Freedom of association . 20 20. Employment relations . 20 21. Freedom of movement and residence . 21 22. Freedom of religion, conscience and belief . 22 23. Political rights . 23 24. Right to privacy . 24 25. Access to information . 24 26. Right to equality and freedom from discrimination . 24 27. Freedom from compulsory or arbitrary acquisition of property . 25 28. Rights of ownership and protection of iTaukei, Rotuman and Banaban lands . 26 29. Protection of ownership and interests in land . 27 30. Right of landowners to fair share of royalties for extraction of minerals . -

Magazine Cover Page-13

VoICE. NET Oct-Dec 2017 VoICE International 1 VoICE International EDITORIAL BOARD UMESH SINHA DHIRENDRA OJHA S D SHARMA DR. AARTI AGGARWAL Editor-in-Chief Election Advisor Associate Editor Election Commission of India Election Election Commission of India Commission of India Commission of India PADMA ANGMO ARIN KUMAR SAFAA E. JASIM LYDIA MACHELI Election Fijian Elections Office Independent High Independent Commission of India Electoral Commission Electoral Commission Iraq Lesotho JANE GITONGA Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission Kenya NAZMA NIZAM VASU MOHAN ADHY AMAN Election Commission of International Foundation International IDEA Maldives for Electoral Systems 2 VoICE International Oct-Dec 2017 VoICE International EDITORIAL BOARD UMESH SINHA S.D SHARMA DR. AARTI AGGARWAL DHIRENDRA OJHA PADMA ANGMO ZUBNAH KHAN Editor-in-Chief Advisor Associate Editor Member Member Member Election Election Election Election Election Fijian Elections Office Commission of India Commission of India Commission of India Commission ofVoICE India Commission International of India * ADVISORY BOARD SAFAA IBRAHIM JASIM JANE GITONGA LYDIA MACHELI MS. NAZMA NIZAM VASU MOHAN ADHY AMAN Member Member Member Member Member Member IHEC, Iraq IEBC Kenya IEC Lesotho Election Commission of IFES International IDEA Maldives DR. ABDUL KHABIR ASADUZZAMAN ZEHRA TEPIC PHUB DORJI DR. FABIO LIMA ADVISORYMOMAND BOARD Election Central Election Election QUINTAS Independent Election Commission, Commission, Commission of Bhutan Superior Electoral Commission of Afghanistan Bangladesh -

CONSTITUTION of the REPUBLIC of FIJI CONSTITUTION of the REPUBLIC of FIJI I

CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI i CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI CONTENTS _______ PREAMBLE CHAPTER 1—THE STATE 1. The Republic of Fiji 2. Supremacy of the Constitution 3. Principles of constitutional interpretation 4. Secular State 5. Citizenship CHAPTER 2—BILL OF RIGHTS 6. Application 7. Interpretation of this Chapter 8. Right to life 9. Right to personal liberty 10. Freedom from slavery, servitude, forced labour and human trafficking 11. Freedom from cruel and degrading treatment 12. Freedom from unreasonable search and seizure 13. Rights of arrested and detained persons 14. Rights of accused persons 15. Access to courts or tribunals 16. Executive and administrative justice 17. Freedom of speech, expression and publication 18. Freedom of assembly 19. Freedom of association 20. Employment relations 21. Freedom of movement and residence 22. Freedom of religion, conscience and belief 23. Political rights 24. Right to privacy 25. Access to information 26. Right to equality and freedom from discrimination 27. Freedom from compulsory or arbitrary acquisition of property 28. Rights of ownership and protection of iTaukei, Rotuman and Banaban lands 29. Protection of ownership and interests in land 30. Right of landowners to fair share of royalties for extraction of minerals 31. Right to education 32. Right to economic participation 33. Right to work and a just minimum wage ii 34. Right to reasonable access to transportation 35. Right to housing and sanitation 36. Right to adequate food and water 37. Right to social security schemes 38. Right to health 39. Freedom from arbitrary evictions 40. -

Fiji's Constitution of 2013

PDF generated: 12 Aug 2019, 19:19 constituteproject.org Fiji's Constitution of 2013 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 12 Aug 2019, 19:19 Table of contents Preamble . 8 CHAPTER 1: THE STATE . 8 1. The Republic of Fiji . 8 2. Supremacy of the Constitution . 9 3. Principles of constitutional interpretation . 9 4. Secular State . 9 5. Citizenship . 10 CHAPTER 2: BILL OF RIGHTS . 11 6. Application . 11 7. Interpretation of this Chapter . 11 8. Right to life . 12 9. Right to personal liberty . 12 10. Freedom from slavery, servitude, forced labour and human trafficking . 13 11. Freedom from cruel and degrading treatment . 14 12. Freedom from unreasonable search and seizure . 14 13. Rights of arrested and detained persons . 14 14. Rights of accused persons . 15 15. Access to courts or tribunals . 17 16. Executive and administrative justice . 18 17. Freedom of speech, expression and publication . 18 18. Freedom of assembly . 19 19. Freedom of association . 20 20. Employment relations . 20 21. Freedom of movement and residence . 21 22. Freedom of religion, conscience and belief . 22 23. Political rights . 23 24. Right to privacy . 24 25. Access to information . 24 26. Right to equality and freedom from discrimination . 24 27. Freedom from compulsory or arbitrary acquisition of property . 25 28. Rights of ownership and protection of iTaukei, Rotuman and Banaban lands . 26 29. Protection of ownership and interests in land . 27 30. Right of landowners to fair share of royalties for extraction of minerals . -

Thursday – 3Rd September 2020

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DAILY HANSARD THURSDAY, 3RD SEPTEMBER, 2020 [CORRECTED COPY] C O N T E N T S Pages Minutes … … … … … … … … … … … 1909 Communications from the Chair … … … … … … … 1909 Presentation of Reports of Committees … … … … … … 1909-1917 (1) Review Report of the Ministry of Youth and Sports 2017/2018 Annual Report (2) Review Report on the COP 23 Presidency Trust Fund Second Semi-Annual Report 2017 (3) Consolidated Annual Review Report on the Ministry of Agriculture 2014 &2015 Annual Reports (4) Annual Review of the National Fire Authority 2013 Annual Report (5) Review Report on the Provincial Councils Volume 2 Report Ministerial Statements … … … … … … … … … 1917-1926 (1) Fiji Airways Fleet Acquisition Public Health (Amendment)(No.2) Bill 2020 … … … … … … 1927-1935 Pharmacy Profession (Amendment) Bill 2020 … … … … … … 1935-1940 Television (Amendment) Bill 2020 … … … … … … … 1940-1942 Companies (Amendment) Bill 2020 … … … … … … … 1943-1953 Immigration (Amendment) Bill 2020 … … … … … … … 1954-1963 Citizenship of Fiji (Amendment) Bill 2020 … … … … … … 1963-1970 Passports (Amendment) Bill 2020 … … … … … … … 1970-1974 Suspension of Standing Orders … … … … … … … … 1974-1975 Adoption Bill 2018 … … … … … … … … … 1975-1987 Ministry of Youth & Sports 2016-2017 Annual Review Report … … … 1987-1993 COP 23 Presidency Trust Fund 2nd Semi-Annual Report 2017 … … … 1993-1999 Inquiry into the Financial State and Overall Viability of Fiji Airways … … … 1999-2015 Inquiry into Freehold Land Held by FSC… … … … … … … 2015-2026 Questions … … … … … … … … … … 2027-2038 Oral Questions (1) Passage of Heavy Goods Trucks - Residential Subdivision (Q/No. 127/2020) (2) Progress on the National Tree Planting Initiative (Q/No. 128/2020) (3) Policies to Reduce Urban Drift (Q/No. 129/2020) (4) VSAT Stations and Tsunami Sirens (Q/No. -

Passports Act 2002

103 ACT NO. 14 OF 2016 I assent. J. K. KONROTE President [6 June 2016] AN ACT TO AMEND THE PASSPORTS ACT 2002 ENACTED by the Parliament of the Republic of Fiji— Short title and commencement 1.—(1) This Act may be cited as the Passports (Amendment) Act 2016. (2) This Act comes into force on a date or dates appointed by the Minister by notice in the Gazette. (3) In this Act, the Passports Act 2002 is referred to as the “Principal Act”. Section 2 amended 2. Section 2 of the Principal Act is amended by— (a) in subsection (1), inserting the following new definitions— ““disciplined force” means— (a) the Republic of Fiji Military Forces; (b) the Fiji Police Force; or (c) the Fiji Corrections Service; 104 Passports (Amendment)—14 of 2016 “Fijian official passport” means a passport issued under section 9A; “peacekeeping duty” means any peacekeeping or peace enforcement mission sanctioned by the Government;”; and (b) in subsection (2), inserting “and a Fijian official passport” after “emergency passport”. New sections 9A, 9B, 9C, 9D and 9E inserted 3. The Principal Act is amended by inserting the following new sections after section 9— “Fijian official passport 9A.—(1) A passport officer may, upon receipt of an application— (a) made in the approved form; and (b) endorsed by the Commander of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces, Commissioner of Police or Commissioner of the Fiji Corrections Service, as the case may be, issue a Fijian official passport to a member of the disciplined force travelling on peacekeeping duties. (2) A person issued with a Fijian official passport under subsection (1) must be a citizen of Fiji. -

Vessel Will Provide Medical Services for 40,000 Fijians

SUNDAY JUNE 3, 2018 l 16 PAGES l ISSUE 11 VOL 9 l WWW.FIJI.GOV.FJ Fijij Focus Mobile hospital The Veivueti after being commissioned in Suva. INSET TOP: Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama with medical staff on the vessel. INSET BOTTOM: Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama on the bridge of the Veivueti. Photos: ERONI VALILI Vessel will provide medical services for 40,000 Fijians NANISE NEIMILA out emergency surgeries, take X-rays, as for someone to have an operation, sel was much needed. screen for pulmonary tuberculosis, the patient is airlifted to Suva. But “The travelling cost from Taveuni LOSE to 40,000 Fijians living perform urgent dental procedures and with the new vessel and services pro- to Labasa and return by boat is about in the maritime islands will more. vided on board this is very efficient,” $60 and we have to think of accom- Cnow access better and mobile “The medical facility is a promise Mr Soqoi said. modation. We are lucky to have rela- medical services on new Govern- fulfilled by my Government. Mereseini Dakuna, 68, who lives tives otherwise it’s an added cost but ment Shipping Services vessel the This vessel will be constantly mov- near Mualevu Village on Vanuaba- with the new vessel providing such Veivueti. ing; its current schedule consists of lavu, shared similar sentiments saying services, it will be a great help to us,” Commissioned by Prime Minister 10 week-long trips, through which Fijians living in the maritime islands she said. Voreqe Bainimarama, the $8million more than 10,000 patients from the would not spend a lot of money to “We are thankful to the Government vessel was specifically designed and far reaches of Fiji are expected to be travel to Suva now. -

Student Visasthe On

Migration and Refugee Division Commentary Student visasthe on Current as atby 19 September 2019 FOI 2019 WARNING This work is protected by copyright. You may download, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) forunder your personal, non-commercial use or educational use within your organisation. ReleasedApart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 all other rights are reserved. AAT © CommonwealthSeptember of Australia 19 Subclasses 570 – 576: Genuine Student - Relevant Assessment Levels and Schedule 5A Criteria (pre 1 July 2016) Contents Overview Genuine intention to stay temporarily • Relevant considerations when determining ‘genuine intention’ Evidentiary requirements – Schedule 5A • Assessment levels o Determining the applicant’s assessment level Visa applications made on or after 27 March 2010 Visa applications made before 27 March 2010 o Determining assessment level when applicant is no longer enrolled o Transitional arrangements for former Subclassthe 560 or 562 visa holders • English language proficiency on o IELTS test ‘taken less than 2 years before the date of the application’ o Alternative to IELTS test The applicable instrument by 2019 o Successful completion of a course ‘less than 2 FOIyears before the date of the application’ o Other ways to meet English language proficiency requirement • Financial Capacity o Funds from an acceptable source Money deposits Successful completion of part of a course Financial institutions Loans, overdrafts, linesunder of credit and credit -

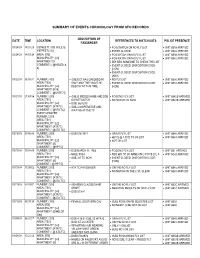

Summary of Events Chronology from Sfo Records Date Time Location

SUMMARY OF EVENTS CHRONOLOGY FROM SFO RECORDS DESCRIPTION OF DATE TIME LOCATION REFERENCES TO WATCHLISTS POLICE PRESENCE PASSENGER 03/24/03 14:03:29 XSTREET1: [ITB AISLE 5] • POSS MATCH ON NO FLY LIST • UNIT 6B59 ARRIVED XSTREET2: [6] • EVENT CLOSED • UNIT 6B42 ARRIVED 03/24/03 14:09:34 AREA: [ITB] • POS MATCH ON NO FLY LIST • UNIT 6B58 ARRIVED MUNICIPALITY: [L3] • POS MATCH ON NO FLY LIST • UNIT 6B42 ARRIVED APARTMENT:[0] • B58 REQ SOMEONE TO CHECK THE LIST COMMENT: [: @AISLE5: & • EVENT CLOSED: DISPOSITION CODE: 6] [NOM] • EVENT CLOSED: DISPOSITION CODE [ADV] 03/22/03 06:06:41 NUMBER: [400] • SUBJECT HAS CHECKED IN • NO FLY LIST • UNIT 6B50 ARRIVED AREA: [TB3] ONLY AND THEY HAVE NO • EVENT CLOSED: DISPOSITION CODE: • UNIT 6B51 ARRIVED MUNICIPALITY: [L2] DESCRY AT THIS TIME [NOM] APARTMENT: [N18] COMMENT: [: @GATE 75] 03/21/03 21:49:56 NUMBER: [200] • SUBJS MIDDLE NAME AND DOB • POSS NO FLY LIST • UNIT 6B42B ARRIVED AREA: [TB1] DO NOT MATCH • NO MATCH ON SUBJ • UNIT 6B41B ARRIVED MUNICIPALITY: [L2] • DOB: 06/06/79 APARTMENT: [ATATC] • SUBJ COOPERATIVE AND COMMENT: [: @ATA TC] WAITING AT THE TC EVENT UPDATED: NUMBER: [200] AREA: [TB1] MUNICIPALITY: [L2] APARTMENT: [ATATC] COMMENT: [: @ATC TC] 03/18/03 07:45:48 NUMBER: [200] • DOB 07311971 • ON NO FLY LIST • UNIT 6B40 ARRIVED AREA: [TB1] • 6B102 @ 1-7072 TO CK LIST • UNIT 6B41 ARRIVED MUNICIPALITY: [L2] • NOT ON LIST APARTMENT: [0] COMMENT: [: @HP TC] 03/15/03 10:08:45 NUMBER: [200] • DOB MARCH 11, 1960 • POSS NO FLY LIST • UNIT 6B1 ARRIVED AREA: [TB1] • MALE SUBJ • REQ 6B1 TO CK NAME -

Challenges Facing Pacific Communities: the Case of Fijians in New Zealand”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. LIVING IN TWO WORLDS “Challenges Facing Pacific Communities: The Case of Fijians in New Zealand” A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Maori & Pacific Development at the University of Waikato By KALISITO VUNIDILO 2006 ABSTRACT Living in two worlds is an insider perspective of how indigenous Pacific Immigrant communities, in this specific case Fijian’s living in New Zealand face the challenges of living two cultures in a developed country like New Zealand. The quest to hold on to one’s indigenous culture while adapting to another, in order to survive the realities of everyday circumstances can be a complicated struggle. The main objective of this research was to collate and analyze information from Fijian families who migrated to New Zealand from 1970’s to the mid 1980’s with reference to the challenges they faced.