Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Studies Association 59Th Annual Meeting

AFRICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION 59TH ANNUAL MEETING IMAGINING AFRICA AT THE CENTER: BRIDGING SCHOLARSHIP, POLICY, AND REPRESENTATION IN AFRICAN STUDIES December 1 - 3, 2016 Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C. PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Benjamin N. Lawrance, Rochester Institute of Technology William G. Moseley, Macalester College LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Eve Ferguson, Library of Congress Alem Hailu, Howard University Carl LeVan, American University 1 ASA OFFICERS President: Dorothy Hodgson, Rutgers University Vice President: Anne Pitcher, University of Michigan Past President: Toyin Falola, University of Texas-Austin Treasurer: Kathleen Sheldon, University of California, Los Angeles BOARD OF DIRECTORS Aderonke Adesola Adesanya, James Madison University Ousseina Alidou, Rutgers University Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Columbia University Brenda Chalfin, University of Florida Mary Jane Deeb, Library of Congress Peter Lewis, Johns Hopkins University Peter Little, Emory University Timothy Longman, Boston University Jennifer Yanco, Boston University ASA SECRETARIAT Suzanne Baazet, Executive Director Kathryn Salucka, Program Manager Renée DeLancey, Program Manager Mark Fiala, Financial Manager Sonja Madison, Executive Assistant EDITORS OF ASA PUBLICATIONS African Studies Review: Elliot Fratkin, Smith College Sean Redding, Amherst College John Lemly, Mount Holyoke College Richard Waller, Bucknell University Kenneth Harrow, Michigan State University Cajetan Iheka, University of Alabama History in Africa: Jan Jansen, Institute of Cultural -

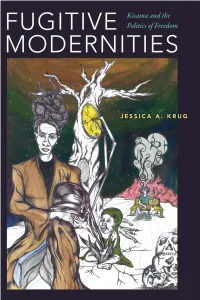

Jessica Krug , Fugitive Modernities: Kisama and the Politics of Freedom (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 280 Pp, Paperback, ISBN 9781478001546

All the contents of this journal, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License Jessica Krug , Fugitive Modernities: Kisama and the Politics of Freedom (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 280 pp, paperback, ISBN 9781478001546. This is a book about the political imaginations and intellectual labor of fugi- tives. It is about people who didn’t write, by choice. — Jessica Krug, Fugitive Modernities I am no scholar of Angola. I am not particularly knowledgeable about Portuguese colonialism; I have learnt the trans-Atlantic slave trade, yes, but no more than other informed readers disturbed by its ongoing afterlives. It is therefore telling that I came across Jessica Krug’s Fugitive Modernities in a conversation with friends similarly unacquainted with West Central Africa and the Americas, but, like me, animated by questions that lie at the heart of this book: How do we write about the disap- peared? How to put into words communities whose worlds have been targeted in acts of mass violence? How do we narrate the worlds of those who actively tried to evade the power that, as Trouillot reminds us, makes and records history? My friends and I focus on post-20th century communities elsewhere upended by other forms of violence, including settler-colonial destruction in Palestine, the Ottoman geno- cide of Armenians, and imperial war in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border regions.1 In contrast, Fugitive Modernities engages the ideas of communities escaping the grip of brutal states and the violence of the trans-Atlantic slave trade around present-day Angola, Colombia and Brazil from the 16th century until today. -

Report: the State of Black Gw Presented by the Black Student Union Fall 2020

REPORT: THE STATE OF BLACK GW PRESENTED BY THE BLACK STUDENT UNION FALL 2020 Email: [email protected] Instagram: @gwubsu Facebook: @GWBSU This report is presented to administrators, faculty, and student leaders at The George Washington University on behalf of the Black community by the Black Student Union. CONTENTS I. CURRENT BLACK ORGANIZATIONS 2 II. EXECUTIVE STATEMENT 3 III. INTRODUCTION 5 IV. HISTORY OF BLACK GW 6 V. COMMUNITY ACHIEVEMENTS 2020 7 A. MEDIA ATTENTION 8 VI. FINANCIAL SUPPORT 9 VII. FALL 2020 SURVEY DATA 11 VIII. ANALYSIS OF SURVEY RESULTS 14 IX. RECOMMENDATIONS 16 X. CONTRIBUTORS 20 XI. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 21 1 CURRENT BLACK ORGANIZATIONS The Black Student Union African Student Association Ethiopian-Eritrean Student Association ALIANZA Black Men's Initiative Black Women's Forum GW National Council of Negro Women GW NAACP GW Black Defiance Queer and Trans People of Color Association Xola Black Girl Mentorship Black Graduate Student Association The Multicultural Business Student Association GW National Society of Black Engineers GW National Association of Black Journalists Young Black Professionals in International Affairs The African Development Initiative Undergraduate Chapter of the Black Law Student Association D.R.E.A.M.S GW National Pan-Hellenic Council Gamma Alpha Phi Chapter of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity Inc. Nu Beta Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc. Kappa Chi Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity Inc. Mu Beta Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. Mu Delta Chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Xi Sigma Chapter of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. The Williams “Black” House The Black Ace Magazine GW Ubuntu 2 EXECUTIVE STATEMENT It is no secret that Black students at The George Washington University do not have an equitable student experience to our peers. -

Transcript: Why Are White American Women Posting As Black and Latinx Women?

The Table Podcast (Jan.-Mar. 2021) Item Type Recording, oral Authors Carney, Courtney Jones; Ferreira, Rosemary Publication Date 2021 Keywords current events; University of Maryland, Baltimore. Intercultural Center; Culture; Ethnicity; Race; University of Maryland, Baltimore Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 03/10/2021 04:34:24 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10713/14810 Transcript: Why Are White American Women Posting as Black and Latinx Women? Producer, Angela Jackson: Warning, in this episode there are mentions of police violence and substance abuse. Please exercise caution for all listeners under thirteen. Courtney Jones Carney Do you remember back in September 2020 when there was all this news about an associate professor at George Washington University who was pretending to be an Afro-Latina from the Bronx? Rosemary Ferreira I do remember that. The professor’s name is Jessica Krug and she was a professor in history and Africana studies. She released a public letter in which she apologized for being a quote, “cultural leech” and a quote, “coward” for lying about her race and ethnicity, because in truth she is a white Jewish woman from suburban Kansas. Courtney Jones Carney So what’s really interesting here is that Krug has built her career as an academic studying African and Caribbean cultures and she’s claimed activist fighting against gentrification and police brutality in New York City. Archived Recording (Jessica Krug) It’s all part of copwatching and all part of the culture. And I realize now that I’m talking about this a little bit institutionally. -

CURRICULUM VITAE John M

CURRICULUM VITAE John M. Janzen January, 2016 I. Education 1967 Ph.D., University of Chicago, Anthropology 1964 M.A., University of Chicago, Anthropology 1963 Certificate in African Studies, University of Paris (Sorbonne) 1961 B.A., Bethel College, North Newton, KS. Social Science & Philosophy II. Teaching Positions Visiting Professor, Gulu University, Uganda. M.A. Program in Medical Anthropology. Nov, 2014 University of Kansas, assoc. prof., 1972-5; professor, 1977- 2014; emeritus professor, 2014- Visiting Professor, Medical University of Vienna, Austria, spring 2004 Visiting Lecturer, Harvard University, Central for Population & Development, March, 2004 University of Cape Town, visiting professor, 1982 American Univ. Cairo, visit. distinguish. prof., Jan., 1983 McGill University, ass't prof., 1969-72 Bethel College, ass't professor, 1967-8; visiting prof., 1976 III. Languages American English: native speaker German: fluent speaker, reading; reasonably proficient, writing. Low-German (Vistula Delta originating Mennonite plautdietsch) French: fluent speaker, reading, writing. KiKongo: fluent speaker, reading, writing. Arabic: one year intensive study for reading, with Mushin Madhi, Oriental Institute, Chicago. IV. Research Experiences and Interests Lower Congo, 1964-6; 1969; 1982; 2013 (social & political organization of Kongo society, economic development; religion; health and patterns of health-care seeking). Eastern & Southern Africa, 1982 & 83 ( distribution and character of "ngoma" healing and interpretation of misfortune). Central Africa (Burundi, Rwanda, E. Zaire), 1994-5 (ethnic conflict, war & trauma healing). West Africa & Sahel (Senegal, Sudan), 2000, 2001, 2004 (religion & healing, esp. Sufism) Western & Central Europe (historic origins and development of aspects of Mennonite society and culture, including the Netherlands, Baltic coast, Russia, also the diaspora in Paraguay and Brazil) 1970, 1977, 1989, 1990, 1993. -

Fugitive Modernities This Page Intentionally Left Blank Fugitive Modernities

Fugitive Modernities This page intentionally left blank Fugitive Modernities Kisama and the politics of freedom JESSICA A. KRUG duke university press Durham & London 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Westchester Library of Congress Cataloguing- in- Publication Data Names: Krug, Jessica A., [date] author. Title: Fugitive modernities : Kisama and the politics of freedom / Jessica A. Krug. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018016917 (print) | lccn 2018019866 (ebook) isbn 9781478002628 (ebook) isbn 9781478001195 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478001546 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Sama (Angolan people) | Fugitive slaves— Angola. | Fugitive slaves— Colombia. | Fugitive slaves— Brazil. Classification: lcc dt1308.s34 (ebook) | lcc dt1308.s34 k78 2018 (print) | ddc 305.896/36— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2018016917 Cover art: Francisco McCurry, We Are Here: 3076. Mixed media on paper, 9 in. × 12 in. Courtesy of the artist. i have long believed that love is not pos si ble in translation, and yet, inevitably, I find myself interpreting ways of seeing the world, of being, of knowing, from one context to another, daily. It goes far deeper than language. This is a book about the po liti cal imagination and intellectual labor of fugitives. It is about people who didn’t write, by choice. And yet, it is a book. A textual artifact created by someone who learned to tell stories and ask questions from those who never read or wrote, but who loves the written word. -

Current Issue

MILESTONESTHE SONJA HAYNES STONE CENTER FOR BLACK CULTURE AND HISTORY fall 2019 · volume 16 · issue 1 unc.edu/depts/stonecenter NEW STONE CENTER DRIVE OPENS AND NEW WEEKNIGHT PARKING RULES SEPT. 19 – NOV. 21 Robert and Sallie Brown Gallery and Museum Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History 19-5917_BCC_Milestones_NL_Fall2019_final.indd 2 8/8/19 7:45 AM 2 MILESTONES · FALL 2019 · VOLUME 16 · ISSUE 1 1619 COLLECTIVE MEMORY(IES) PROJECT Confirmed symposium participants include: Jessica A. Krug is Assistant Professor of History at George Washington University whose work focuses on politics, ideas, and cultural practices in West Central Africa and the African Diaspora, and maroon societies in the early modern period. She is deeply interested in intellectual histories of those who never wrote documents and the use of embodied knowledge for both research and teaching. Her book Fugitive Modernities: Politics and Identity Outside the State in Kisama, Angola, and the Americas, c. 1594-Present, interrogates the political practices and discourses through which those who fled from slavery and the violence of the slave trade in Angola forged coherent political communities outside of, and in opposition to, state politics. Chief Lynette Allston is the Chief and Tribal Council Chair of the Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia, one of 11 Tribes officially recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia. She is co-author of the book entitled, DoTraTung, which offers a compelling look at the history, culture and lifestyle of the Nottoway Indians whose Community House and Interpretive Center is located in Capron, Virginia. Chief Allston is the former President of the Board of Rawls Museum Arts, Courtland Virginia. -

The Protest Issue SPRING 2021 2 ART CONTRIBUTOR: ANDI ARNOVITZ

The Protest Issue SPRING 2021 2 ART CONTRIBUTOR: ANDI ARNOVITZ Coat of the Agunot, 2010. Digital scans of antique ketubot, threads. 60.2 x 59.4 in. Read AJS Perspectives online at Photo by Avshlom Avital. Permission for use of the ketubot courtesy of the National Library of Israel. © 2010 Andi Arnovitz. Courtesy of the artist. associationforjewishstudies.org 2 | AJS PERSPECTIVES | SPRING 2021 The Protest Issue SPRING 2021 From the Editors 6 Urgent Witness: Spaces of Belonging 57 in Jewish Argentina Essay Contributors 8 Natasha Zaretsky Art Contributors 9 From Israel’s Black Panthers’ Protest to 60 a Transnational MENA Jewish Solidarity The Jewish Hercules: How Sports Created 17 Aviad Moreno Space for Hellenic Judaism in Salonica Makena Mezistrano Jewish Symbols in German Gangsta Rap: 64 A Subtle Form of Protest Prophetic Protest in the Hebrew Bible 19 Max Tretter Marian Kelsey The Ordeal of Scottsboro 66 A Color-Blind Protest of Jewish 25 Stephen J. Whitfield Exceptionalism and Jim Crow Wendy F. Soltz Reading Prophetic Protest without 69 Anti-Judaism White People’s Work, or What Jessica Krug 28 Ethan Schwartz Teaches Us about White Jewish Antiracism Naomi S. Taub Violence Justified: Resistance among 71 the Hasmoneans and Hong Kongers Alternative Rituals as Protest 30 Dr. V Lindsey Jackson The Profession Early Rabbinic Reluctance to Protest 34 Matthew Goldstone The Invisible Meḥiẓah 74 Jodi Eichler-Levine The 1943 Jewish March on Washington, 36 through the Eyes of Its Critics A Protest Novel That Went Unheeded 78 Rafael Medoff Josh Lambert A Golem for Protest: Julie Weitz’s My Golem 42 When Your Book Is Protested: 82 Melissa Melpignano Lessons in Communal Knowing Claire Sufrin Uprising against Butchers! 46 Julia Fermentto-Tzaisler A Protest against the JCC Conception 85 of Jewish Studies This Is Brazil: Jewish Protests under 48 Benjamin Schreier Democracy and Dictatorship Michael Rom After the Pittsburgh Shooting: 88 A Scholar Cries for Justice Allyship and Holding One’s Own Accountable: 54 Rachel Kranson The New Jewish Labor Movement Susan R. -

Fugitive Modernities Fugitive Modernities

Kisama and the FUGITIVE Politics of Freedom MODERNITIES JESSICA A. KRUG Fugitive Modernities Fugitive Modernities isama JESSICA A. KRUG Durham & London © Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Westchester Library of Congress Cataloguing- in- Publication Data Names: Krug, Jessica A., [date] author. Title: Fugitive modernities : Kisama and the politics of freedom / Jessica A. Krug. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, . | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identiers: (print) | (ebook) (ebook) (hardcover : alk. paper) (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: : Sama (Angolan people) | Fugitive slaves— Angola. | Fugitive slaves— Colombia. | Fugitive slaves— Brazil. Classication: . (ebook) | . (print) | . / — dc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / Cover art: Francisco McCurry, We Are Here: . Mixed media on paper, in. × in. Courtesy of the artist. that love is not pos si ble in translation, and yet, inevitably, I nd myself interpreting ways of seeing the world, of being, of knowing, from one context to another, daily. It goes far deeper than language. is is a book about the po liti cal imagination and intellectual labor of fugitives. It is about people who didn’t write, by choice. And yet, it is a book. A textual artifact created by someone who learned to tell stories and ask questions from those who never read or wrote, but who loves the written word. It is an act of translation. It is a love letter. It is an inadequate and perhaps unintelligible love letter to and for those who do not read. -

National Endowment for the Humanities Grant Awards and Offers, December 2013

NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES GRANT AWARDS AND OFFERS, DECEMBER 2013 ALABAMA (2) $150,399 Tuscaloosa University of Alabama Outright: $50,400 [Fellowships for University Teachers] Project Director: Margaret Abruzzo Project Title: Good People and Bad Behavior: Changing Views of Sin, Evil, and Moral Responsibility in the 18th and 19th Centuries Tuskegee Tuskegee University Outright: $99,999 [Humanities Initiatives: HBCUs] Project Director: Loretta Burns Project Title: A Critical Reappraisal of Booker T. Washington: A Tuskegee Humanities Initiative Project Description: A two-year archival digitization, faculty-student research, and course development project on the work and legacy of Booker T. Washington, to take place at Tuskegee University. ALASKA (3) $14,969 Anchorage Municipality of Anchorage, Anchorage Municipal Libraries Outright: $5,988 [Preservation Assistance Grants] Project Director: Angela Demma Project Title: Anchorage 1% for Art Program and Anchorage Museum Exterior Sculpture Conservation Assessment Project Description: A conservation assessment of 90 outdoor sculptures from Anchorage's 1% for Art Program and five additional outdoor sculptures and a Japanese cannon from World War II that are part of the Anchorage Museum's collection. The collection to be assessed includes works by local, national, and international artists such as James Schoppert, Nancy Taylor Stonington, Edward Brownlee, Mauricio Robalino, William King, Dennis Oppenheim, and Antony Gormley. The sculptures are located throughout Anchorage near public -

Chapter 1: Introduction

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Building Community and Capacity: Institutionalized Faculty Development in Community Colleges Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/06p452d8 Author Krug, Jessica Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Building Community and Capacity: Institutionalized Faculty Development in Community Colleges A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education by Jessica Marion Michele Krug 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Building Community and Capacity: Institutionalized Faculty Development in Community Colleges by Jessica Marion Michele Krug Doctor of Education University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Robert A. Rhoads, Chair Based on the presumptions that faculty are critical to student success and that faculty in the community college sector are largely underprepared to serve the diversity of students they encounter, this study sought to examine how community colleges create and sustain their faculty development programs. The faculty development programs selected for this study have high participation of faculty across disciplines, including both adjunct and full-time faculty, and are permanent fixtures on their campuses instead of relying on grant funding or other temporary sources of funding that could eventually be phased out. Further, institutions in this study are improving student outcomes across their campuses, particularly of low-income students and students of color. Utilizing a multi-case study design based on semi-structured interviews, document analysis and observations of public spaces, this study looked holistically and in-depth at institutionalized faculty development programs at three community colleges across the ii country: Bradley Community College, Pomelo College and High Hill College, all pseudonyms. -

Human Rights Education & Black Liberation

International Journal of Human Rights Education Volume 5 Issue 1 Human Rights Education and Black Article 1 Liberation 2021 Volume 5, Special Issue: Human Rights Education & Black Liberation Monisha Bajaj University of San Francisco, [email protected] Susan Roberta Katz University of San Francisco, [email protected] Lyn-Tise Jones [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/ijhre Part of the Education Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Recommended Citation Bajaj, Monisha; Katz, Susan Roberta; and Jones, Lyn-Tise. (2021) . "Volume 5, Special Issue: Human Rights Education & Black Liberation," International Journal of Human Rights Education, 5(1) . Retrieved from https://repository.usfca.edu/ijhre/vol5/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Human Rights Education by an authorized editor of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 5 International Journal of Human Rights Education Photographs by Stephen Shames Special Issue Human Rights Education & Black Liberation Monisha Bajaj, Susan Roberta Katz, and Lyn-Tise Jones Table of Contents Editorial Introduction 1. Bajaj, M., Katz, S.R., & Jones, L.T. (2021). Human Rights Education & Black Liberation. International Journal of Human Rights Education, 5(1), 1-16. Research Articles 2. Ross, L.J., & Bajaj, M. (2021). “My Life's Work Is to End White Supremacy”: Perspectives of a Black Feminist Human Rights Educator.