Content & Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting Your Business

BUSINESS LEARNING CURVES 13 POINTS OF REFERENCE THAT YOU CAN PUT TO WORK FOR YOUR ENTERPRISE PROTECTING YOUR BUSINESS SEIB INSURANCE & REINSURANCE COMPANY DEPUTY CEO AND COO ELIAS CHEDID THE RECAP The role of insurance in developing Qatar’s economy- and why it pays for QATAR your SME to have a safety net ENTERPRISE AGILITY AWARDS 2015 CREATING The second annual SUSTAINABLE Qatar Enterprise Agility Awards, Entrepreneur IMPACT of the Year QATARI SMES AWARDED CONTRACTS BY QDB AND QATAR SHELL AMRO AHMED TALKS ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 9 772312 595000 > DECEMBER 2015 | WWW.ENTREPRENEUR.COM/ME | QAR15 DECEMBER 2015 CONTENTS 16 Amro Ahmed, Qatar Local Content and SME Manager, Qatar Shell 16 14 22 54 INNOVAtor: ProtECTING YOUR THE RECAP SKILLSET THE VALUE OF BUSINEss ENTERPRISE AGILITY Innovation happens ProDUCTION IN CREATING Seib Insurance & Reinsurance ACHIEVERS 2015 outside of the classroom SUstAINABLE IMPACT Company Deputy CEO and The second annual Qatar Three things entrepreneurs Qatari SMEs awarded COO Elias Chedid Enterprise Agility Awards, can teach MBAs, and contracts by QDB and Qatar The role of insurance in Entrepreneur of the Year guess what? It all involves Shell developing Qatar’s economy- staged in association with hands-on experience in the Amro Ahmed talks economic and why it pays for your SME Doha Bank market. development to have a safety net 72 38 ‘TREPONOMICS: SKILLSET PRO Promoting SMEs as key The Diderot effect drivers of innovation and Olympian and entrepreneur engines for global trade James Clear talks about the and growth vicious cycle that ensues Marc Proksch analyzes when you spend a bit, then some external and internal spend a bit more, and then factors to consider for your spend even more. -

GNFN Tabloid Harvest 11.Qxd

Inside Football kick-off - 3 Norfolk launch - 4 Good work - 6 Community care - 9 GOOD NEWS ▲ FOR NORWICH & NORFOLK Harvest 2011: FREE Celebrate faith - 12 Norwich foodbank appeals for tonnes of food ■ Norwich Foodbank has launched a harvest appeal to "None of this could have happened without the won- "We resorted to borrowing a raise six tonnes of food in just two months and revealed derful support we have received from local people who tin of soup from next door plans to set up distribution centres across Norfolk. want to help their neighbours in need via our local to feed our 18-month-old Manager of the Christian charity, Grant Habershon, Christian charity. However to keep pace with the daughter. The problems revealed that the demand for the emergency food demand and our plans we are now launching our 2011 came when my partner got parcels is growing every month. Harvest Appeal to collect six tonnes of donated food in ill and received no sick pay. "In June we provided 253 local people with three days just two months," said Grant. It was snowing and we were of emergency food and in July we fed 279 local people. Foodbank is appealing for help from churches, struggling to afford food Over 40% of these people were under 16. We have schools, Cubs, Brownies and other organizations and and heating. In the end the seen the demand for our services increase each month supporters during September and October to organize cupboards were bare. I don't since we launched in October last year. -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 05-13 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter Of

Federal Communications Commission FCC 05-13 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 04-227 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) ELEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: January 14, 2005 Released: February 4, 2005 By the Commission: Chairman Powell issuing a statement; Commissioners Copps and Adelstein concurring and issuing a joint statement. TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................................1 A. Scope of this Report..................................................................................................................2 B. Summary of Findings ..............................................................................................................4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2004 ...................................................................4 2 General Findings .........................................................................................................7 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING......16 A. Cable Television Service.......................................................................................................16 1. General Performance.................................................................................................17 2. Capital Acquisition and Disposition.........................................................................33 -

Business Unusual: Collective Action Against Bribery in International Business

Business unusual: collective action against bribery in international business Article (Published Version) Dávid-Barrett, Elizabeth (2019) Business unusual: collective action against bribery in international business. Crime, Law and Social Change, 71 (2). pp. 151-170. ISSN 0925-4994 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/70211/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Crime Law Soc Change https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-017-9715-1 Business unusual: collective action against bribery in international business Elizabeth Dávid-Barrett1 # The Author(s) 2017. -

2009 Annual Report

Fiscal Year 2009 Annual Financial Report And Shareholder Letter January 2010 To the Shareholders and Cast Members of The Walt Disney Company: As I was drafting this letter, word came about the passing of a true Disney legend, Roy E. Disney. Roy devoted the better part of his life to our Company, and during his 56 year tenure, he was involved on many levels with many businesses, most notably animation. No one was a bigger champion of this art form than Roy, and it was at his urging that we returned to a full commitment to animation in the mid-1980s. Roy also introduced us to Pixar in the 1990s, a relationship that has proven vital to our success. Roy understood the essence of Disney, and his passion for the Company, his appreciation of its past and his keen interest in its future will be sorely missed. Last year was both an interesting and challenging one for your Company. On the positive side, we released two extraordinary animated films, Up and The Princess and the Frog that exemplify the very best of what we do. We received the go-ahead from China’s government to build a new theme park in Shanghai. We acquired Marvel Entertainment, whose portfolio of great stories and characters and talented creative staff complement and strengthen our own. And we reached an agreement to distribute live-action films made by Steven Spielberg’s DreamWorks SKG. At the same time, we faced a severe global economic downturn and an acceleration of secular challenges that affect several of our key businesses. -

Supplier Directory Managed Sites

Supplier Directory Managed Sites WHRSourcing.com | [email protected] Q3 2018 Your New Procurement Services Provider Guest Supply is now recognized as a Procurement Services Provider for Wyndham Hotel Group! Our FF&E Division, established in 2000, has become an industry leader in FF&E procurement. We are a recognized partner with top management companies across the country and value the long term relationship we have built with our clients. We believe in a direct, upfront approach to pricing and project management where our clientele is fully aware of all aspects of the job throughout the process. Our services are all inclusive and our dedication and involvement remains until the end of each successful project. We provide our customers with a full range of services including design consultation, purchasing, installation coordination and project management for new construction and hotel renovation projects. As part of Guest Supply, we are able to o er an unrivaled level of fi nancial stability, as well as the support of the largest sales team in the industry. For more information contact your Territory Manager or call 1.800.772.7676 Guest Supply®, a Sysco® Company • 300 Davidson Avenue • Somerset, NJ 08873 • guestsupply.com • ©2017 Guest Supply®, a Sysco® Company ©2018 Worldwide Sourcing Solutions, Inc. All products and services are provided by Guest Supply®, a Sysco® Company and not Wyndham Worldwide Corporation (WWC) or its a liates. Neither WWC nor its a liates are responsible for the accuracy or completeness of any statements made in this advertisement, the content of this advertisement (including the text, representations and illustrations) or any material on the listed supplier’s website to which the advertisement provides a link or a reference. -

1 September 2019

SEPTEMBER 2019 1 DISCLAIMER This report presents the findings of a commissioned study on the lessons learned of the Yemen Emergency Crisis Re- sponse Project (ECRP). The views expressed in this study are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP, and of the World Bank, the Social Fund for Development (SFD) and the Public Works Project (PWP). Furthermore, the designations employed herein, their completeness and presentation of information are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the United Nations Development Programme. Copyright 2019 By United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 60th Meter Road P.O.Box: 551 Sana’a, Republic of Yemen Website: http://ye.undp.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of UNDP TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 ACRONYMS 2 I. INTRODUCTION 3 II. COUNTRY CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND TO THE ECRP 4 COUNTRY SITUATION / CONTEXT 4 OVERVIEW OF THE ECRP 4 III. MORE THAN THE SUM OF ITS PARTS: INNOVATIONS IN PARTNERSHIP AND COLLABORA- TION 6 1. RATIONALE, FRAMING AND FORMALIZATION OF THE PARTNERSHIP 6 2. STRATEGIC VALUE AND CONTRIBUTION OF THE ECRP PARTNERSHIP 9 3. COLLABORATION AND WORKING TOGETHER IN PRACTICE 11 IV. TOWARDS A NEW PARADIGM FOR DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE IN CONFLICT CONTEXTS 14 1. STRATEGIC INNOVATION: STRENGTHENING RESILIENCE IN PROTRACTED CRISES 14 2. BRIDGING THE HUMANITARIAN-DEVELOPMENT NEXUS 32 3. -

Partnerships for Women's Health

The United Nations University was established as a subsidiary organ of the United Nations by General Assembly resolution 2951 (XXVII) of 11 December 1972. It functions as an international community of scholars engaged in research, postgraduate training and the dis- semination of knowledge to address the pressing global problems of human survival, development and welfare that are the concern of the United Nations and its agencies. Its activities are devoted to advanc- ing knowledge for human security and development and are focused on issues of peace and governance and environment and sustainable development. The University operates through a worldwide network of research and training centres and programmes, and its planning and coordinating centre in Tokyo. Partnerships for women’s health Partnerships for women’s health Striving for best practice within the UN Global Compact EDITED BY MARTINA TIMMERMANN AND MONIKA KRUESMANN © United Nations University, 2009 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations University. United Nations University Press United Nations University, 53-70, Jingumae 5-chome, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-8925, Japan Tel: +81-3-5467-1212 Fax: +81-3-3406-7345 E-mail: [email protected] general enquiries: [email protected] http://www.unu.edu United Nations University Office at the United Nations, New York 2 United Nations Plaza, Room DC2-2062, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: +1-212-963-6387 Fax: +1-212-371-9454 E-mail: [email protected] United Nations University Press is the publishing division of the United Nations University. -

Tech-Notes #119

In this PDF version, click on the bookmark tap to the left. It will provide you with navigation features to this edition. http://www.Tech-Notes.tv October 27, 2003 Tech-Note – 119 Established May 18, 1997 Our purpose, mission statement, this current edition, archived editions and other relative information is posted on our website. This is YOUR forum! Editor's Comments LARCAN-USA/Tech-Notes Seminar Up date By Larry Bloomfield The response to the LARCAN-USA/Tech-Notes Seminar has really been impressive. We’ve got folks flying in from the San Francisco Bay Area, Albuquerque, NM and Anchorage, Alaska. As of today, we have a total of 50 registered for all three venues. It is the same seminar in three different venues; Portland, OR, Eugene, OR and Medford, OR on November 4th, 5th and 6th and it is FREE. Its open anyone interested and it’s not too late to register. (We need a head count for both food and chairs – yes, we’re going to feed you.) All interested parties should RSVP by Friday, October 31, 2003. For maps to venues, visit: www.Tech-Notes.TV - Select Educational Opportunities. Registrations forms are there also in PDF. If you have trouble doing the PDF thing, download it, fill it in and Fax it to: (503) 217-0712. You can also e- mail a filled in copy to [email protected]. The subject matter will be LPTV, Digital Translators, Analog Translators, LPFM, FM Translators and Trick of the Trade. The scheduled presenters are David Hale, VP LARCAN-USA, Dr. -

Certified Third-Party Interfaces E78960-01

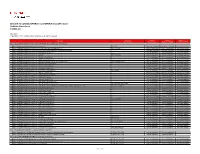

Oracle® Hospitality OPERA Cloud Services Products Certified Third-Party Interfaces E78960-01 January 2019 Copyright © 2019, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. OPERA Cloud OPERA Cloud Interface Services Services Enterprise Professional Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Third-Party Channel Managers Cloud Service Opera Hospitality Distibution Connector to AxisRooms Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector for Channel Manager by yieldPlanet S.A. Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector for TravelClick Channel Manager (EzYield) by TravelClick Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Aeroplan Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Availpro Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Avenues Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Book Assist Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Booking Expert by Nexteam S.r.l. Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Booking.com Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Cyllenius Cloud Service General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to DerbySoft -

Validated Interfaces with OPERA

Oracle® Hospitality OPERA 5 and OPERA Cloud Products Validated Interfaces F23596-04 May 2021 Copyright © 2021, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Interface OPERA 5 OPERA 5 Interface OPERA Cloud Part Number On-Premise Hosted by Oracle Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Third-Party Channel Managers Cloud Service Opera Hospitality Distibution Connector to AxisRooms OPA_AXIS Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector for Channel Manager by yieldPlanet S.A. OPA_YLDPLANET General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector for TravelClick Channel Manager (EzYield) by TravelClick Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Controlled Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Aeroplan Cloud Service General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Availpro OPA_AVAILPRO General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Avenues Cloud Service General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Book Assist Cloud Service General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Booking Expert by Nexteam S.r.l. Cloud Service OPA_BOOKINGEXPERT General Availability General Availability General Availability Oracle Hospitality Distribution Connector to Booking.com Cloud -

Signature Redacted ___Signature Redacted

Online Independent Film Distribution - What is missing? By Perihan AbouZeid BBA Business Administration The American University in Cairo, 2009 SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION ARCHNES AT THE MASSACH . -!TT 1IN;STITUTE OF CHNOLOLGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2015 JUN 2 4 2015 @2015 Perihan AbouZeid. All rights reserved. LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: MIT Sloan School of Management May 8, 2015 Sign ature redacted Certified by: V Scott Stern David Sarnoff Professor of Management of Technology Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: __________Signature redacted Maur -Herson Director, MBA Program MIT Sloan School of Management 2 Online Independent Film Distribution - What is missing? By Perihan AbouZeid Submitted to MIT Sloan School of Management on May 8, 2015 in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Business Administration. ABSTRACT This thesis proposes a new model for online platforms for independent films. Today, platforms such as Netflix, iTunes, and YouTube are in the face of major industry challenges: more competitors are entering the market; consumers are demanding more diverse content and higher quality service; and cost of content acquisition keeps increasing. In addition, the independent film industry has a fragmented value chain, which makes it challenging for filmmakers to fund and distribute their films. By applying the platforms framework proposed by Prof.