Interview with Harry Haven Kendall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sakaide Port Tourist Information

Sakaide Port Tourist Information http://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/cruise/ Home of Sanuki Udon Noodles Kagawa Prefecture is known as Udon Prefecture. You can enjoy going from one udon shop to the next only in this Udon Prefecture. One of the must-visit spots is the local udon shops attached to udon noodle factories. It's wonderful to eat freshly boiled udon noodles in an at-home environment. It's not too much to say that Sakaide is the birthplace of the Sanuki Udon Noodles and you can enjoy each shop’s boast of noodles, dashi soup, and toppings such as tempura. Location/View Access Season Year-round Sakaide Tourism Association Related links https://www.sakaide-kankou.net/ Contact Us[Community Revitalization Office, Industry Division, Construction and Economic Affairs Department, City of Sakaide] TEL: +81-877-44-5015 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.city.sakaide.lg.jp/index.html Yasoba's Tokoroten agar crystal noodles You can enjoy famous tokoroten noodles born in the Edo period, in front of "Yasoba's spring water," which is believed to have been running from ancient times. The texture of the slippery and smooth noodles is addictive. You can find your favorite taste among choices like vinegar soy sauce, brown sugar syrup, kinako soy bean powder, and more. Kiyomizuya Location/View 759-1 Nishinoshocho, Sakaide, Kagawa 762-00021 Access 20 min. via car from port (5.4km) Season Mid March to November Yasoba's Tokoroten agar noodles Kiyomizuya Related links http://www.yasoba.com/ Contact Us[Kiyomizuya ] TEL: +81-877-46-1505 E-Mail:[email protected] Website: http://www.yasoba.com/ Sakaide Three Kintoki Kintoki Mikan mandarin oranges, Kintoki Ninjin carrots, and Kintoki Imo sweet potatoes are Sakaide's local specialties. -

Shikoku Island Tour ( Feb 21 – Mar 3, 2022 )

758 Kapahulu Avenue Suite 220 Honolulu, Hawaii 96816 Tel: (808) 739-9010 Fax: (808) 735-0142 TA#4988 Email address: [email protected] Shikoku Island Tour ( Feb 21 – Mar 3, 2022 ) HIGHLIGHTS of the TOUR: Bus tour goes over most of the bridges that connects SHIKOKU. 1 night in Kansai Airport, 2 nights in Takamatsu, 2 nights in Kochi, 3 nights in Matsuyama- Dogo Onsen, and 1 night in Himeji Hands on Experience: making Sanuki Udon and Uchiwa “fan” Last day on 3/3, Kobe Beef Teppanyaki Steak Lunch in Kobe MONDAY, Feb 21st HONOLULU – OSAKA/KANSAI____ 8:00a.m. Please meet NADINE SHIMABUKURO, at the Japan Airlines baggage check-in area located at Lobby #5 at Honolulu International Airport. NADINE will give you your “E” ticket and help you check-in. Please have your passport ready. 10:45a.m. Depart on JAPAN AIRLINES FLT. #791 bound for Osaka/ Kansai, Japan. A meal will be served one hour after take-off. In-flight meals: LUNCH: Main entrée’with miso soup, salad, ice cream, & cookies. Prior to arrival: Cold Cut Sandwich with Yogurt Throughout the flight, you can enjoy complimentary soft drinks like JAL's SKY TIME drink (real “Yuzu” Citrus Juice), other soft drinks, assorted beers, wines, sake, coffee, tea, and green tea. Complimentary In-flight Movies like the new up-to-date ones, Japanese, Chinese, & Korean Movies. Over 40 Music Channels and limited games too. TUESDAY, Feb 22nd OSAKA / KANSAI _____________ You will be passing thru International Date Line so you will be losing a day. 3:50p.m. -

瀬戸内海 Dr Shinya Yamanaka Was Awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize in Seto Naikai— Japan’S Inland Sea Physiology Or Medicine, Becoming Japan’S 19Th Nobel Laureate

Japanese Nobel Laureate 瀬戸内海 Dr Shinya Yamanaka was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize in Seto Naikai— Japan’s Inland Sea Physiology or Medicine, becoming Japan’s 19th Nobel laureate. Seto Naikai 瀬戸内海 is the name of of the three most famous bridges in Japan. Dr Yamanaka of Kyoto University Gurdon, done half a century ago in Japan’s largest inland sea—the Seto Inland Walking over the Kintai Bridge is a novel received the prize for the discovery 1962 (coincidentally the year of Dr Sea. This 450km-long body of water lies experience as you climb and descend the that mature cells can be Yamanaka’s birth). Dr Gurdon between three of Japan’s main islands, five beautiful but quite steep arches. Of the reprogrammed to become pluripotent showed it was possible to clone Kyushu, Honshu and Shikoku. Connected Seto Inland Sea’s giant modern bridges, through two straits to the Pacific Ocean and (a biological term meaning ‘capable tadpoles from adult cells, overturning only the westernmost has a pedestrian one to the Sea of Japan, the Seto Inland of giving rise to several different cell the accepted science of the day. crossing and it will take you considerably a Sea has long been an important domestic longer to cross. It is almost 60 kilometres types’). The co-winner of the 2012 and international trading route. In an interview with Nobelprize.org’s from Onomichi (a town famous for its prize was Sir John B. Gurdon Adam Smith, Dr Yamanaka Before the advent of the Sanyo Main Line, photogenic port and streets) to Imabari in (Cambridge University). -

Itinerary & Price List

Itinerary & Price List June – November 2021 Guntû is a little hotel floating on the Seto Inland Sea Since October 2017, guntû has roamed the Seto Inland Sea The sea reflects upon the silver hull like a mirror; inside, soothing interiors are finished with the finest wood. Calm on a journey to rediscover Setouchi’s delights. awaits in one of just 19 cabins and the spacious public areas. Discover the allure of Setouchi as our ship becomes Encounters with people, with landscapes, with cuisine. a part of the region’s serene natural beauty and rich cul- A guntû journey is one of a kind. ture̶ exploring, expressing, and linking together its charms. Relax and feel as one with the scenery outside as the hue of the mountain silhouettes and the water changes New discoveries and encounters await on every route, from moment to moment. in every season, and every time you come aboard. We look forward to sharing an exhilarating time with you. guntû crew Seto Inland Sea “Setouchi Roaming” This is one of the concepts behind guntû voyages. After de- parting from the home port of Bella Vista Marina in Onomichi, without docking at any ports, guntû roams Setouchi and an- chors alongside island silhouettes at night. To go ashore on islands alongside the ship’s route and see local lifestyles and cultures, our guests take dedicated speed boats designed by guntû’s architect, Yasushi Horibe. guntû Speed Boat 2 About suites The guntû Suite Grand Suite Terrace Suite with Open-Air Bath Terrace Suite [ 1 cabin, approx. 90m2 / 969 ft2 ] [ 2 cabins, approx. -

Example of the Seto Inland Sea in Japan

Island Sustainability II 131 Development and preservation of tourist resources: example of the Seto Inland Sea in Japan H. Gotoh1, Y. Maeno1, M. Takezawa1, K. Shimizu1 & M. Shimizu2 1Nihon University, Tokyo, Japan 2Tekken Corporation, Japan Abstract Japan has a total of 29 national parks, 55 quasi-national parks, and numerous environmental preservation areas. The Seto Inland Sea National Park consists of the ocean area separating Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu; three of the main islands of Japan. It serves as an international waterway, connecting the Pacific Ocean to the Sea of Japan and Osaka Bay, and it provides a sea transport link to the industrial centers of the Kansai region, including Osaka and Kobe. Before the construction of the Sanyo Main Railroad Line, it was the main transportation link between Kansai and Kyushu. The Inland Sea region is known for its moderate climate, stable year-round temperatures, and relatively low levels of rainfall. Since the 1980s, its northern and southern shores have been connected by the three routes of the Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Project, including the Great Seto Bridge, which serves both railroad and automobile traffic. The Inland Sea measures 450 km from east to west, and 15 to 55 km from north to south. In most places, the Seto Inland Sea is relatively shallow and the average depth is 37.3 m; the deepest point is 105 m. There are approximately 3,000 islands located in the Seto Inland Sea, including the larger islands Awajishima and Shodoshima. Many of the smaller islands are uninhabited. In this paper, the present state and future potential of some of these islands are examined and proposed within the context of tourism in Seto Inland Sea. -

The Geography of Knowledge Production: Connecting Islands and Ideas

The Geography of Knowledge Production: Connecting Islands and Ideas Andrew B. Bernard Andreas Moxnes Yukiko U. Saito Tuck@Dartmouth Princeton & U. Oslo Waseda U. CEP, CEPR and NBER CEPR RIETI Preliminary International Trade Online, April 17, 2020 1 / 47 Introduction The production of ideas: y = f (i1;i2;::) The quality/quantity of ideas might depend on 1 The composition of teams (matching function) F e.g. quality of team members and team size. 2 The productivity of teams (match quality). Economic integration likely to affect both 1) and 2). We know little about the impact of economic integration on these margins. 2 / 47 What we do Use universe of geocoded patent data from Japanese Patent Office. Natural experiment: Connecting a Japanese island with bridges. Study the activities of inventors with large fall in travel time before/after the connections. I Inventor productivity. I Team characteristics: size, quality, distance to co-inventors. 3 / 47 Literature Scientific production I Catalini et al (2020), Waldinger (2011), Iaria et al (2018), Agrawal and Goldfarb (2007) Distance & spread of knowledge (citations): I Comin et al (2012), Head et al (2019), Jaffe et al (1993) Teams and innovation I Akcigit et al (2018) Geography and innovation I Railroads: Perlman (2016) The bridge literature I Akerman (2009), Armenter et al (2014), Arnarson (2016), Brooks and Donavan (2019). 4 / 47 Today Data, measurement and stylized facts. Research design. Results. 5 / 47 Data Patent data from JPO, 1981 to 2005. For each (Japanese) patent, we know I the applicant(s) and the set of inventors. I the work address (geocode) of each inventor and applicant. -

Bridge Design

Bridge Design Introduction 22.02.2021 ETH Zurich | Chair of Concrete Structures and Bridge Design | Bridge Design Lectures 1 1 What is a Bridge? 22.02.2021 ETH Zurich | Chair of Concrete Structures and Bridge Design | Bridge Design Lectures 2 ‘Living Root Bridges’, Meghalaya plateau, India Photo Credit: Ferdinand Ludvig, professor for green technologies in landscape architecture at the Technical University of Munich; https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/living-bridges-india-scn/index.html 2 What is a Bridge? 22.02.2021 ETH Zurich | Chair of Concrete Structures and Bridge Design | Bridge Design Lectures 3 Akashi Kaikyō Bridge, Awaji Island and Kobe, Japan (1998) Owner/Designer: Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Authority Contractors: Obayashi Corp., Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Solétanche Bachy, Taisei Corp., Kawada Industries, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd., Yokogawa Bridge Corp., … (More than 100 contractors involved) Type: Suspension Materials: Steel (cables, pylons, deck truss), Reinforced Concrete (anchorages) Longest main span in the world = 1,991 m Overall length = 3,911 m Pylon height = 283 m Roadway bridge References: https://structurae.net/en/structures/akashi-kaikyo-bridge https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/98julaug/worlds.cfm Photo Credit: http://eskipaper.com/pic/getsecond 3 What is a Bridge? Some definitions: “a structure spanning and providing passage over a river, chasm, road, or the like.” [Dictionary.com] “a structure carrying a pathway or roadway over a depression or obstacle (such as a river)” [Merriam-Webster] “a structure that is built over a river, road, or railway to allow people and vehicles to cross from one side to the other” [Cambridge Dictionary] “A bridge is a structure that is built over a railway, river, or road so that people or vehicles can cross from one side to the other.” [Collins Dictionary] “A structure carrying a road, path, railway, etc. -

Itinerary & Price List

Itinerary & Price List December 2020 - May 2021 Guntû is a little hotel floating on the Seto Inland Sea Greetings from guntû Drift across the waters of the Seto Inland Sea, encountering Since launching in October 2017, guntû has been roaming across Setouchi, the region's island chains and local ways of life as you become connected to the peaceful environment. Pass the as people call the region in western Japan where strings of small islands are time any way you want in serenity and comfort on board. The woven together by the calm waters of the Seto Inland Sea. shape of the mountains and islands, and the color of the sea, Setouchi is a beautiful and mysterious world unto itself, shifts with each passing moment. with more than 700 islands floating in a seascape of 23,000 Our ship itself becomes a part of the Seto Inland Sea's gentle square kilometers and 7,000 kilometers of shoreline. natural beauty and rich culture -exploring, expressing, and linking together its charms. Journey across a sea that spar- To rediscover the allure of Setouchi, kles like a treasure chest and discover the allure of Setouchi. we have prepared eight routes for the winter of 2020 and spring of 2021, including five brand-new routes. Seto Inland Sea Relax aboard our ship resembling a Japanese ryokan that blends into the gentle scenery of Setouchi. We look forward to welcoming you on guntû. Concept of guntû voyages “Setouchi Roaming” is one of the concepts behind guntû voy- guntû crew ages. After departing from the home port of Bella Vista Marina in Onomichi, without docking at any ports, guntû roams Setouchi and anchors alongside island silhouettes at night. -

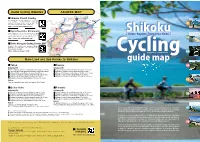

Guide to 28 Cycling Routes Throughout Ehime Prefecture Along with Events and Other Handy Info

Useful Cycling Websites ACCESS MAP Okayama Hiroshima Shodoshima ■Shikoku Circuit Cycling JR Seto-Ohashi-Line Seto-Chuo Expwy Created as part of the "Challenge 1,000 km Project" to encourage Kobe-Awaji-Naruto Expwy cyclists to make a circuit of the entire island of Shikoku and JR Kotoku-Line experience its abundance of natural scenery and culture. They Takamatsu Chuo IC 01 now accept both domestic and international applicants! Nishi-seto Expwy https://cycling-island-shikoku.com/ (Shimanami-Kaido) Kagawa Naruto IC Tokushima IC JR Yosan-Line Imabari IC Tokushima Expwy ■CycloTourisme Shimanami JR Dosan-Line Tokushima Offers suggestions for cycling journeys along the Matsuyama IC Matsuyama Expwy Setouchi Shimanami Kaido. Covers everything including [Shikoku Ehime・Kagawa・Tokushima・Kochi ] route overviews, cyclist rescue services and more. https://www.cyclo-shimanami.com/ Ehime JR Mugi-Line 02 Kochi Expwy Kochi Kochi IC ■Ehime Marugoto Cycling Service Site Suzaki East IC Seiyo Uwa IC A guide to 28 cycling routes throughout Ehime Prefecture along with events and other handy info. Shimanto-Cho Mobile app also available. Chuo IC https://ehime-cycling.jp/HOME JR Yodo-Line 03 CyclingPresented by Tourism Shikoku Main Land and Sea Routes to Shikoku guide map ■Tokyo ■Nagoya 04 By Railway (JR): By Railway (JR): ● Tokyo to Takamatsu: Sunrise Seto overnight limited express (approx. 9 hr. 30 min.) ● Nagoya to Okayama: Nozomi Shinkansen (approx 1 hr. 37 min.) ● Tokyo to Okayama: Nozomi Shinkansen (between 3 hr. 9 min. and 3 hr. 22 min.) Okayama to Takamatsu: Marine Liner rapid train (55 min.) Okayama to Takamatsu: Marine Liner rapid train (55 min.) Okayama to Matsuyama: Limited Express Shiokaze (2 hr. -

Arab Republic of Egypt the Project for Improvement of the Bridge

Arab Republic of Egypt General Authority for Roads, Bridges and Land Transport (GARBLT) Arab Republic of Egypt The Project for Improvement of the Bridge Management Capacity Project Completion Report July 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency Nippon Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. Chodai Co., Ltd. EI JR 15-134 Project Area Abbreviation chart Abbreviation English ASTM American Society for Testing and Materials AASHTO American Association of State Highway and Transport Officials BMS Bridge Management System BIV Bridge Inspection Vehicle C/P Counterpart CSV Comma-Separated Values DO District Office DSL Domain-Specific Language GARBLT General Authority for Roads, Bridges and Land Transport GM General Manager HCD Head of Central Department HTB High Tension Bolt JCC Joint Coordination Comittee JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency JIS Japanese Industrial Standards M/M Minutes of Meeting MOT Ministry of Transport NDT Non-Destructive Test ODA Official Development Assistance OS Operating System OST On-site Training PC Prestressed Concrete PDM Project Design Matrix pH Potential Hydrogen PM Project Manager PMS Photo Management System PO Plan of Operation RC Reinforced Concrete Rebar Reinforcing Steel Bar R/D Record of Discussion TWG Technical Working Group WG Working Group Table of Contents 1 Outline of the Project ............................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 The -

Using History to Reinforce Ethics and Equilibrium

AC 2010-895: USING HISTORY TO REINFORCE ETHICS AND EQUILIBRIUM Wilfrid Nixon, University of Iowa Wilfrid Nixon is a Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Iowa, and has been on the faculty there since 1987. In addition to his research on winter highway maintenance, he has also conducted research into student learning, and ways in which faculty can enhance such learning. He has been involved both with the Civil Engineering Division of ASEE and with the ASCE Committee on Faculty Development, and has also both attended and served as a mentor at ExCEEd Teaching Workshops. He plays bad golf, and also dances the Argentine Tango. Page 15.1326.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2010 Using History to Reinforce Ethics and Equilibrium Abstract The American Society of Civil Engineers in the 2 nd edition of the “Body of Knowledge” (BOK2) document identify the level of achievement for outcome 11 (Contemporary Issues and Historical Perspectives) as: Analyze the impact of historical and contemporary issues on the identification, formulation, and solution of engineering problems and analyze the impact of engineering solutions on the economy, environment, political landscape, and society. This is not an outcome that is readily achieved in most civil engineering undergraduate classes when taught in their traditional format. To address this, the author decided to introduce a segment into each offering of two different classes, the classes being statics and bridge engineering. The statics class is taught twice a week over a semester (15 weeks) and the bridge engineering class is taught one evening a week, again over a semester. -

Anchor Offshore at T

A three-day voyage to enjoy contemporary art and timeless island culture Eastward route (2 nights, 3 days) anchor ofshore at Tamano and Tomonoura (P_V2) Schedule Contents are subject to change without prior notice depending on the reservation date, the weather and sea conditions on the day. Departure from Bella Vista Marina ( 4:30 p.m. ) Pass through the Onomichi Strait 1st Day Octopus purchase of the coast of Mihara, Hiroshima Innoshima Bridge, the nightscape of Mizushima industrial complex, the Great Seto Bridge Anchor ofshore at Tamano Of-ship activity: Visit to an art island such as Naoshima and Inujima Departure from of the coast of Tamano 2nd Day Of-ship activity : Tour of Honjima’s Kasashima Historical Preservation District Anchor ofshore at Tomonoura Great Seto Bridge About Honjima Located at the center of the Shiwaku Islands, Honjima has a vista of the Great Seto Bridge connecting Okayama Prefecture on Honshu and Kagawa Prefecture on Shikoku. The main base for a local band of pirates, Honjima also has a large number of historic buildings constructed by Shiwaku This three-day journey invites passengers to explore the old and new carpenters, who utilized shipbuilding techniques to construct temples and houses across Kagawa, Okayama and even as far away as Osaka. Along with Toyomachi Mitarai in Osaki-Shimojima, the Kasashima village of Honjima is part of a nationally-designated historical preservation district on allure of Setouchi, from the reinvented art island of Inujima to Honjima the islands of the Seto Inland Sea. in the Shiwaku Islands, once the home base of a local band of pirates.