William E. Lass: "The First Attempt to Organize Dakota Territory."

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laws of Wisconsin Territory

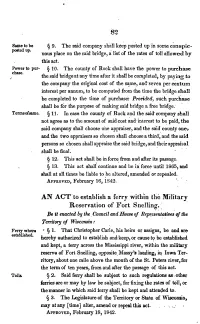

82 Same to be § 9. The said company shall keep posted up in some conspic- posted up. uous place on the said bridge, a list of the rates of toll allowed by this act. Power to pur- § 10. The county of Rock shall have the power to purchase chase. the said bridge at any time after it shall be completed, by paying to the company the original cost of the same, and seven per centum interest per annum, to be computed from the time the bridge shall be completed to the time of purchase: Provided, such purchase shall be for the purpose of making said bridge a free bridge. Terms ofsame. § 11. In case the county of Rock and the said company shall not agree as to the amount of said cost and interest to be paid, the said company shall choose one appraiser, and the said county one, and the two appraisers so chosen shall choose a third, and the said persons so chosen shall appraise the said !midge, and their appraisal shall be final. § 12. This act shall be in force, from and after its passage. § 13. This act shall continue and be in force until 1865, and shall at all times be liable to he altered, amended or repealed. APPROVED, February 16, 1S42. AN ACTA() establish a ferry within the Military Reservation of Fort Snelling.. Be it enacted by the Council and House of Representatives of the Territory of Wisconsin : Ferry where ' § 1. That Christopher Carle, his heirs or assigns, be and are established. hereby authorized to establish and keep, or cause to be established and kept, a ferry across the Mississippi river, within the military reserve of Fort Snelling, opposite, Massy's landing, in, Iowa Ter- ritory, about one mile above the mouth of the St. -

Edmund Rice (1638) Association Newsletter

EDMUND RICE (1638) ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER Published Summer, Fall, Winter, Spring by the Edmund Rice (1638) Association, 24 Buckman Dr., Chelmsford MA 01824-2156 The Edmund Rice (1638) Association was established in 1851 and incorporated in 1934 to encourage antiquarian, genealogical, and historical research concerning the ancestors and descendants of Edmund Rice who settled in Sudbury, Massachusetts in 1638, and to promote fellowship among its members and friends. The Association is an educational, non-profit organization recognized under section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Edmund Rice (1638) Assoc., Inc. NONPROFIT ORG 24 Buckman Drive US POSTAGE Chelmsford, MA 01824-2156 PAID Return Postage Guarantee CHELMSFORD MA PERMIT NO. 1055 1 Edmund Rice (1638) Association Newsletter _____________________________________________________________________________________ 24 Buckman Dr., Chelmsford MA 01824 Vol. 79, No. 1 Winter 2005 _____________________________________________________________________________________ President's Column Inside This Issue Our Rice Reunion 2004 seemed to have attracted cousins who normally Editor’s Column p. 2 don’t attend, so the survey instigated by George Rice has proven particularly useful. One theme reunion attendees asked for appears to be a desire to hear more history of Database Update p. 5 our early Puritan forefathers. US Census Online p. 6 To that end, we have found an expert in the history of the Congregationalists Family Thicket V p. 7 who succeeded the Puritans. He is Rev. Mark Harris who, among other things, teaches at the Andover Newton Theological Seminary. He will speak at our Annual Meeting Genetics Report p. 8 2005 on the evolution of Puritans from the 1700s, where Francis Bremer left off, to the Rices In Kahnawake p. -

Teacher’S Guide Teacher’S Guide Little Bighorn National Monument

LITTLE BIGHORN NATIONAL MONUMENT TEACHER’S GUIDE TEACHER’S GUIDE LITTLE BIGHORN NATIONAL MONUMENT INTRODUCTION The purpose of this Teacher’s Guide is to provide teachers grades K-12 information and activities concerning Plains Indian Life-ways, the events surrounding the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the Personalities involved and the Impact of the Battle. The information provided can be modified to fit most ages. Unit One: PERSONALITIES Unit Two: PLAINS INDIAN LIFE-WAYS Unit Three: CLASH OF CULTURES Unit Four: THE CAMPAIGN OF 1876 Unit Five: BATTLE OF THE LITTLE BIGHORN Unit Six: IMPACT OF THE BATTLE In 1879 the land where The Battle of the Little Bighorn occurred was designated Custer Battlefield National Cemetery in order to protect the bodies of the men buried on the field of battle. With this designation, the land fell under the control of the United States War Department. It would remain under their control until 1940, when the land was turned over to the National Park Service. Custer Battlefield National Monument was established by Congress in 1946. The name was changed to Little Bighorn National Monument in 1991. This area was once the homeland of the Crow Indians who by the 1870s had been displaced by the Lakota and Cheyenne. The park consists of 765 acres on the east boundary of the Little Bighorn River: the larger north- ern section is known as Custer Battlefield, the smaller Reno-Benteen Battlefield is located on the bluffs over-looking the river five miles to the south. The park lies within the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana, one mile east of I-90. -

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV Maps and Descriptions Denis White March 2020

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV maps and descriptions Denis White March 2020 (Image NOAA, Landsat, Copernicus; Presentation Google Earth) A contribution to the corpus of materials created by James Omernik and colleagues on the Ecological Regions of the United States, North America, and South America The page size for this document is 9 inches horizontal by 12 inches vertical. Table of Contents Content Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Geographic patterns in Minnesota 1 Geographic location and notable features 1 Climate 1 Elevation and topographic form, and physiography 2 Geology 2 Soils 3 Presettlement vegetation 3 Land use and land cover 4 Lakes, rivers, and watersheds; water quality 4 Flora and fauna 4 3. Methods of geographic regionalization 5 4. Development of Level IV ecoregions 6 5. Descriptions of Level III and Level IV ecoregions 7 46. Northern Glaciated Plains 8 46e. Tewaukon/BigStone Stagnation Moraine 8 46k. Prairie Coteau 8 46l. Prairie Coteau Escarpment 8 46m. Big Sioux Basin 8 46o. Minnesota River Prairie 9 47. Western Corn Belt Plains 9 47a. Loess Prairies 9 47b. Des Moines Lobe 9 47c. Eastern Iowa and Minnesota Drift Plains 9 47g. Lower St. Croix and Vermillion Valleys 10 48. Lake Agassiz Plain 10 48a. Glacial Lake Agassiz Basin 10 48b. Beach Ridges and Sand Deltas 10 48d. Lake Agassiz Plains 10 49. Northern Minnesota Wetlands 11 49a. Peatlands 11 49b. Forested Lake Plains 11 50. Northern Lakes and Forests 11 50a. Lake Superior Clay Plain 12 50b. Minnesota/Wisconsin Upland Till Plain 12 50m. Mesabi Range 12 50n. Boundary Lakes and Hills 12 50o. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 3, 2008 No. 90 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. and was THE JOURNAL On January 5, 2007, 1 day after his called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The 40th birthday, Rabbi Goodman became pore (Mr. JACKSON of Illinois). Chair has examined the Journal of the a United States citizen. last day’s proceedings and announces Rabbi Goodman is the co-author of f to the House his approval thereof. ‘‘Hagadah de Pesaj,’’ which is the most Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- widely used edition of The Pesach Hagadah used in Latin America. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER nal stands approved. Singled-out by international leaders PRO TEMPORE f for both his ideas and hard work, The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Felipe became vice president of the fore the House the following commu- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the World Union of Jewish Students. nication from the Speaker: gentlewoman from Nevada (Ms. BERK- He is one of 12 members of The Rab- WASHINGTON, DC, LEY) come forward and lead the House binic Cabinet of The Chancellor of The June 3, 2008. in the Pledge of Allegiance. Jewish Theological Seminary and I hereby appoint the Honorable JESSE L. Ms. BERKLEY led the Pledge of Alle- serves as a member of The Joint Place- JACKSON, Jr., to act as Speaker pro tempore giance as follows: ment Commission of The Rabbinical on this day. -

Memorial of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wisconsin, Praying That the Title of the Menomonie Indians to Lands Within That Territory May Be Extinguished

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 1-28-1839 Memorial of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Wisconsin, praying that the title of the Menomonie Indians to lands within that territory may be extinguished Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Doc. No. 148, 25th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1839) This Senate Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , ~ ' ' 25th CoNGREss, [SENATE.] [ 14-8] 3d Session. '. / o.r Til~ t.EtitsLA.Tff:E .Ass·EMBtY oF, THE TERRITORY oF W'ISCONSIN, l'RAYING That the title of the MenQ'!JfQ,~zie IJ_y]j(J.1JS. tq ?fJnds within that Territory ni'ay be extinguished. JA~u~RY 28, ~839. Referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs, and ordered to be printed. To the honorable the Senate and House of Representotives of the United States of America in Congress assembled: The memorial of the Legislative Assembly of the 'rerritory of Wisconsin RESPECTFULLY REPRESENTS : That the title of the Menomonie nation of Indians is yet unextinguished to that portion of our Territory lying on the northwest side of, and adjacent to, the Fox river of'Green bay, from the portage of the Fox and Wisconsin _rivers to the mouth of Wolf river. -

Vol. 01/ 6 (1916)

REVIEWS OF BOOKS History of Stearns County, Minnesota. By WILLIAM BELL MITCHELL. In two volumes. (Chicago, H. C. Cooper Jr. and Company, 1915. xv, xii, 1536 p. Illustrated) These two formidable-looking volumes, comprising some fif teen hundred pages in all, are an important addition to the literature of Minnesota local history. The author is himself a pioneer. Coming to Minnesota in 1857, he worked as surveyor, teacher, and printer until such time as he was able to acquire the St. Cloud Democrat. He later changed the name of the paper to the St. Cloud lournal, and, after his purchase of the St. Cloud Press in 1876, consolidated the two under the name St. Cloud Journal-Press, of which he remained editor and owner until 1892. During this period he found time also to discharge the duties of receiver of the United States land office at St. Cloud, and to serve as member of the state normal board. It would appear, then, that Mr. Mitchell, both by reason of his long resi dence in Stearns County and of his editorial experience, was preeminently fitted for the task of writing the volumes under review. Moreover, he has had the assistance of many of the prominent men of the county in preparing the general chapters of the work. Among these may be noted chapters 2-6, dealing with the history of Minnesota as a whole during the pre-territorial period, by Dr. P. M. Magnusson, instructor in history and social science in the St. Cloud Normal; a chapter on "The Newspaper Press" by Alvah Eastman of the St. -

Sioux Falls, 1877-1880

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2004 A Dakota Boomtown: Sioux Falls, 1877-1880 Gary D. Olsen Augustana College - Sioux Falls Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Olsen, Gary D., "A Dakota Boomtown: Sioux Falls, 1877-1880" (2004). Great Plains Quarterly. 268. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/268 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A DAKOTA BOOMTOWN SIOUX FALLS, 1877 .. 1880 GARY D. OLSON The "Dakota boom" is a label historians have claiming of land by immigrant and American almost universally adopted to describe the would, be farm owners in the plains of Dakota period of settlement in Dakota Territory be, Territory and adjacent areas. Less well known tween the years 1878 and 1887. The term is the impact this rapid, large,scale settling of "boom" has been applied to this period largely the land had on the rise and growth of townsites because of the volume of land claimed and the aspiring to become prosperous ci ties. We know rapid increase in Dakota Territory's popula, the rural landscape changed as sod houses and tion that occurred during those years. Most dugouts were erected, fields plowed, and trees accounts of this time period have treated the planted. -

Beginnings (Pp. 0-23)

Minnesota Territory established. Benedictines arrived in Minnesota. Free school opened in Stearns County. Bill No. 70 of Minnesota's Eighth Legislative Session incorporated the St. John's Seminary. Abbot Rupert Seidenbusch, OSB, St. John's first abbot, blessed on June 2. Pope Pius IX created Archbishop James Gibbons of Baltimore as first American car- dinal. Vicariate Apostolic of Northern Minnesota established on February 12. Abbot Alexius Edelbrock, OSB, St. John's second abbot, blessed on October 24. St. john the Baptist Parish established on December 12. English began to replace German in parish announcements. BEGINNINGS In 1875 the American Church - including its faithful in central Minnesota - was making headlines. Pope Pius IX Vicariate of had named Archbishop James Gibbons the first American Northern cardinal and had established the Vicariate of Northem Min- Minnesota nesota from the then diocese of St. Paul. The apostolic i vicar's jurisdiction stretched for 600 miles east to west and a, 250 miles north to south. That May, Most Rev. Rupert Seidenbusch, OSB, was consecrated the vicariate's bishop in i St. Mary's Church in St. Cloud. Shortly after his consecra- tion, Bishop Seidenbusch resigned as the first abbot of the j then abbey of St. Louis on the Lake, "situated in the most healthy part of Minnesota,' and moved to St. Cloud to administer the vicariate which numbered 14,000 immigrant \ settlers and 25,000 Indians, and a clergy of twenty-one Bene- dictine and eight diocesan priests. That December this \ bishop answered the request of twenty settlers who lived near the abbey to establish the St. -

Inventory of Art in the Minnesota State Capitol March 2013

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Minnesota Historical Society - State Capitol Historic Site Inventory of Art in the Minnesota State Capitol March 2013 Key: Artwork on canvas affixed to a surface \ Artwork that is movable (framed or a bust) Type Installed Name Artist Completed Location Mural 1904 Contemplative Spirit of the East Cox. Kenyon 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Winnowing Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Commerce Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Stonecutting Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Mill ing Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Mining Willett Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Navigation Willett Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Courage Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 Senate Chamber Mural 1904 Equality Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 Senate Chamber Mural 1904 Justice Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 Senate Chamber Mural 1904 Freedom Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 Senate Chamber Mural 1905 Discovers and Civilizers Led Blashfield. Edwin H. 1905 Senate Chamber, North Wall ' to the Source of the Mississippi Mural 1905 Minnesota: Granary of the World Blashfield, Edwin H. 1905 Senate Chamber, South Wall Mural 1905 The Sacred Flame Walker, Henry Oliver 1903 West Grand Staircase (Yesterday. Today and Tomorrow) Mural 1904 Horticulture Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 West Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Huntress Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 West Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Logging Willett. -

H. Doc. 108-222

1776 Biographical Directory York for a fourteen-year term; died in Bronx, N.Y., Decem- R ber 23, 1974; interment in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, Hacken- sack, N.J. RABAUT, Louis Charles, a Representative from Michi- gan; born in Detroit, Mich., December 5, 1886; attended QUINN, Terence John, a Representative from New parochial schools; graduated from Detroit (Mich.) College, York; born in Albany, Albany County, N.Y., October 16, 1836; educated at a private school and the Boys’ Academy 1909; graduated from Detroit College of Law, 1912; admitted in his native city; early in life entered the brewery business to the bar in 1912 and commenced practice in Detroit; also with his father and subsequently became senior member engaged in the building business; delegate to the Democratic of the firm; at the outbreak of the Civil War was second National Conventions, 1936 and 1940; delegate to the Inter- lieutenant in Company B, Twenty-fifth Regiment, New York parliamentary Union at Oslo, Norway, 1939; elected as a State Militia Volunteers, which was ordered to the defense Democrat to the Seventy-fourth and to the five succeeding of Washington, D.C., in April 1861 and assigned to duty Congresses (January 3, 1935-January 3, 1947); unsuccessful at Arlington Heights; member of the common council of Al- candidate for reelection to the Eightieth Congress in 1946; bany 1869-1872; elected a member of the State assembly elected to the Eighty-first and to the six succeeding Con- in 1873; elected as a Democrat to the Forty-fifth Congress gresses (January 3, 1949-November 12, 1961); died on No- and served from March 4, 1877, until his death in Albany, vember 12, 1961, in Hamtramck, Mich; interment in Mount N.Y., June 18, 1878; interment in St. -

The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: an Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 1 1976 The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J. Sheran Timothy J. Baland Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Sheran, Robert J. and Baland, Timothy J. (1976) "The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Sheran and Baland: The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An THE LAW, COURTS, AND LAWYERS IN THE FRONTIER DAYS OF MINNESOTA: AN INFORMAL LEGAL HISTORY OF THE YEARS 1835 TO 1865* By ROBERT J. SHERANt Chief Justice, Minnesota Supreme Court and Timothy J. Balandtt In this article Chief Justice Sheran and Mr. Baland trace the early history of the legal system in Minnesota. The formative years of the Minnesota court system and the individuals and events which shaped them are discussed with an eye towards the lasting contributionswhich they made to the system of today in this, our Bicentennialyear.