Gender Issues and the Slave Narratives:" Incidents in the Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2006 Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction Miya G. Abbot University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Abbot, Miya G., "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1487 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. Abbot entitled "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of , with a major in English. Miriam Thaggert, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary Jo Reiff, Janet Atwill Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. -

In Memoriam Frederick Dougla

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection CANNOT BE PHOTOCOPIED * Not For Circulation Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection / III llllllllllll 3 9077 03100227 5 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection jFrebericfc Bouglass t Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection fry ^tty <y /z^ {.CJ24. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Hn flDemoriam Frederick Douglass ;?v r (f) ^m^JjZ^u To live that freedom, truth and life Might never know eclipse To die, with woman's work and words Aglow upon his lips, To face the foes of human kind Through years of wounds and scars, It is enough ; lead on to find Thy place amid the stars." Mary Lowe Dickinson. PHILADELPHIA: JOHN C YORSTON & CO., Publishers J897 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Copyright. 1897 & CO. JOHN C. YORSTON Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection 73 7^ In WLzmtxtrnm 3fr*r**i]Ch anglais; "I have seen dark hours in my life, and I have seen the darkness gradually disappearing, and the light gradually increasing. One by one, I have seen obstacles removed, errors corrected, prejudices softened, proscriptions relinquished, and my people advancing in all the elements I that make up the sum of general welfare. remember that God reigns in eternity, and that, whatever delays, dis appointments and discouragements may come, truth, justice, liberty and humanity will prevail." Extract from address of Mr. -

Introduction

Introduction R. J. Ellis One of the most influential books ever written, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly was also one of the most popular in the nineteenth century. Stowe wrote her novel in order to advance the anti-slavery cause in the ante-bellum USA, and rooted her attempt to do this in a ‘moral suasionist’ approach — one designed to persuade her US American compatriots by appealing to their God-given sense of morality. This led to some criticism from immediate abolitionists — who wished to see slavery abolished immediately rather than rely upon [per]suasion. Uncle Tom's Cabin was first published in 1852 as a serial in the abolitionist newspaper National Era . It was then printed in two volumes in Boston by John P. Jewett and Company later in 1852 (with illustrations by Hammatt Billings). The first printing of five thousand copies was exhausted in a few days. Title page, with illustration by Hammatt Billings, Uncle Tom’s Cabin Vol. 1, Boston, John P. Jewett and Co., 1852 During 1852 several reissues were printed from the plates of the first edition; each reprinting also appearing in two volumes, with the addition of the words ‘Tenth’ to ‘One Hundred and Twentieth Thousand’ on the title page, to distinguish between each successive re-issue. Later reprintings of the two-volume original carried even higher numbers. These reprints appeared in various bindings — some editions being quite lavishly bound. One-volume versions also appeared that same year — most of these being pirated editions. From the start the book attracted enormous attention. -

Discovering the Underground Railroad Junior Ranger Activity Book

Discovering the Underground Railroad Junior Ranger Activity Book This book to:___________________________________________belongs Parents and teachers are encouraged to talk to children about the Underground Railroad and the materials presented in this booklet. After carefully reading through the information, test your knowledge of the Underground Rail- road with the activities throughout the book. When you are done, ask yourself what you have learned about the people, places, and history of this unique yet difficult period of American history? Junior Rangers ages 5 to 6, check here and complete at least 3 activities. Junior Rangers ages 7 to 10, check here and complete at least 6 activities. Junior Rangers ages 10 and older, check here and complete 10 activities. To receive your Junior Ranger Badge, complete the activities and then send the booklet to our Omaha office at the address below. A ranger will go over your answers and then return your booklet along with an official Junior Ranger Badge for your efforts. Please include your name, age, and mailing address where you would like your Junior Ranger Badge to be sent. National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program National Park Service 601 Riverfront Drive Omaha, Nebraska 68102 For additional information on the Underground Railroad, please visit our website at http://www.nps.gov/ugrr This booklet was produced by the National Park Service Southeast Region, Atlanta, Georgia To Be Free Write about what “Freedom” means to you. Slavery and the Importance of the Underground Railroad “To be a slave. To be owned by another person, as a car, house, or table is owned. -

African American Heritage Trail

Robinson family home 1 Rokeby Museum Described as “unrivaled” by the National Park Service, Rokeby Museum is a National Historic Landmark and preeminent Underground Railroad site. “Free and Safe: One of many farm buildings The Underground Railroad in Vermont,” introduces visitors to Simon and Jesse – two historically documented fugitives from slavery who were sheltered at Rokeby in the 1830’s. The exhibit traces their stories from slavery to freedom, introduces the abolitionist Robinson family who called Rokeby home for nearly 200 years, and explores the turbulent decades leading up to the Civil War. Once a thriving Merino sheep farm, Rokeby retains eight historic farm buildings filled with agricultural artifacts along with old wells, stone walls and fields. Acres of pastoral landscape invite a leisurely stroll or a hike up the trail. Picnic tables are available for dining outdoors. Rowland Thomas and Rachel Gilpin Robinson Vermont Folklife 3 Center Daisy Turner, born in June 1883 to ex-slaves Alexander and Sally Turner in Grafton, Vermont, embodied living history during her 104 years as a Vermonter. Her riveting style of storytelling, reminiscent of West African griots, wove the history of her family from slavery until her death in 1988 as Vermont’s oldest citizen. The Vermont Folklife Center recorded over 60 hours of interviews with Daisy. A selection of these audio recordings, plus photographs and video relating to Daisy and the Turner family, are part of an interactive listening exhibit for visitors to the Center. The full collection of Great Convention Turner materials in the Folklife Center Archive is available 2 Historic Marker to qualified researchers by appointment only. -

Resolution to Support and Celebrate Juneteenth Within the Utah System of Higher Education

RESOLUTION TO SUPPORT AND CELEBRATE JUNETEENTH WITHIN THE UTAH SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION WHEREAS, Juneteenth, also known as Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, Liberation Day, and Emancipation Day, celebrates the emancipation of those who had been enslaved in the United States; and WHEREAS, the nineteenth day of June is officially recognized as the day when enslaved peoples in Texas learned of the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation that had been issued by President Lincoln more than two years earlier; and WHEREAS, during this time, the nation celebrates the accomplishments, inventions, triumphs, and resiliency of African American, African, and Black peoples in this country; and WHEREAS, each Juneteenth is an opportunity for the Board to reflect on the previous year’s efforts and renew the System and institutional commitment to closing opportunity and attainment gaps for African American, African, and Black students, staff, and faculty persisting within Utah higher education; and WHEREAS, the Board commits to recognize, rectify, improve, strengthen, and support African American, African, and Black peoples; and WHEREAS, the Board acknowledges that failing to affirm and celebrate the diverse cultural identities and histories that exist in Utah and its institutions reinforces systemic racism, trauma, and erasures that impact students, staff, and faculty; and WHEREAS, institutions of higher education are curators of knowledge and advanced learning that are expected to provide an exhaustive, complex, and inclusive account of history; and WHEREAS, although -

African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship

Catholic University Law Review Volume 43 Issue 1 Fall 1993 Article 4 1993 Ironic Encounter: African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship Dena S. Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Dena S. Davis, Ironic Encounter: African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship, 43 Cath. U. L. Rev. 109 (1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol43/iss1/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC ENCOUNTER: AFRICAN-AMERICANS, AMERICAN JEWS, AND THE CHURCH- STATE RELATIONSHIP Dena S. Davis* I. INTRODUCTION This Essay examines a paradox in contemporary American society. Jewish voters are overwhelmingly liberal and much more likely than non- Jewish white voters to support an African-American candidate., Jewish voters also staunchly support the greatest possible separation of church * Assistant Professor, Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. For critical readings of earlier drafts of this Essay, the author is indebted to Erwin Chemerinsky, Stephen W. Gard, Roger D. Hatch, Stephan Landsman, and Peter Paris. For assistance with resources, the author obtained invaluable help from Michelle Ainish at the Blaustein Library of the American Jewish Committee, Joyce Baugh, Steven Cohen, Roger D. Hatch, and especially her research assistant, Christopher Janezic. This work was supported by a grant from the Cleveland-Marshall Fund. 1. In the 1982 California gubernatorial election, Jewish voters gave the African- American candidate, Tom Bradley, 75% of their vote; Jews were second only to African- Americans in their support for Bradley, exceeding even Hispanics, while the majority of the white vote went for the white Republican candidate, George Deukmejian. -

William Cooper Nell. the Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

William Cooper Nell. The Colored Patriots of the American ... http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/nell/nell.html About | Collections | Authors | Titles | Subjects | Geographic | K-12 | Facebook | Buy DocSouth Books The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons: To Which Is Added a Brief Survey of the Condition And Prospects of Colored Americans: Electronic Edition. Nell, William Cooper Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities supported the electronic publication of this title. Text scanned (OCR) by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Images scanned by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Text encoded by Carlene Hempel and Natalia Smith First edition, 1999 ca. 800K Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. © This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text. Call number E 269 N3 N4 (Winston-Salem State University) The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South. All footnotes are moved to the end of paragraphs in which the reference occurs. Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references. All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively. All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively. -

Frederick Douglass Helped to Organize the Famous 1850 Anti-Fugitive Sla

Frederick Douglass helped to organize the famous 1850 Anti-Fugitive Sla... http://blog.syracuse.com/news/print.html?entry=/2012/02/frederick_dougl... Frederick Douglass helped to organize the famous 1850 Anti-Fugitive Slave Law Convention in Cazenovia Published: Tuesday, February 14, 2012, 5:55 AM The Post-Standard By Frederick Douglass — abolitionist, eloquent orator, writer, editor, and women’s rights advocate — was born a slave in Maryland in February 1817 or 1818. He chose Feb. 14 as his birthday. Douglass succeeded on his second attempt at freedom in 1838, and settled in New Bedford, Mass. William Lloyd Garrison heard Douglass speak at an antislavery meeting and invited him to join the American Anti-Slavery Society. After moving to Rochester in the 1840s, Gerrit Smith of Peterboro convinced Douglass to join his effort to abolish slavery by political means. Douglass spoke at anti-slavery conventions in Peterboro and throughout Central New York and worked with Smith in organizing the famous 1850 Courtesy OHA Anti-Fugitive Slave Law Convention in This daguerreo type, fro m the co llectio n o f the Onondaga Historical Cazenovia. Association, is the earliest kno wn pho to graph o f Frederick Do uglass. It was taken in the early 1840s, when Douglass was about 26. In 1863, after the Emancipation, Douglass traveled to Syracuse and elsewhere delivering passionate recruitment speeches. “The arm of the slave is the best defense against the arm of the slaveholder,” Douglass implored. His work as an abolitionist, his stance on behalf of justice and equal opportunity, and his defense of women’s rights brought international recognition. -

Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad

BIOGRAPHY from Harriet Tubman CONDUCTOR ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD by Ann Petry How much should a person sacrifi ce for freedom? QuickTalk How important is a person’s individual freedom to a healthy society? Discuss with a partner how individual freedom shapes American society. Harriet Tubman (c. 1945) by William H. Johnson. Oil on paperboard, sheet. 29 ⁄" x 23 ⁄" (73.5 cm x 59.3 cm). 496 Unit 2 • Collection 5 SKILLS FOCUS Literary Skills Understand characteristics Reader/Writer of biography; understand coherence. Reading Skills Notebook Identify the main idea; identify supporting sentences. Use your RWN to complete the activities for this selection. Vocabulary Biography and Coherence A biography is the story of fugitives (FYOO juh tihvz) n.: people fl eeing someone’s life written by another person. We “meet” the people in from danger or oppression. Traveling by a biography the same way we get to know people in our own lives. night, the fugitives escaped to the North. We observe their actions and motivations, learn their values, and incomprehensible (ihn kahm prih HEHN see how they interact with others. Soon, we feel we know them. suh buhl) adj.: impossible to understand. A good biography has coherence—all the details come The code that Harriet Tubman used was together in a way that makes the biography easy to understand. incomprehensible to slave owners. In nonfi ction a text is coherent if the important details support the incentive (ihn SEHN tihv) n.: reason to do main idea and connect to one another in a clear order. something; motivation. The incentive of a warm house and good food kept the Literary Perspectives Apply the literary perspective described fugitives going. -

Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, James, "Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution" (2015). Masters Theses. 23. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/23 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memory as Torchlight: Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2015 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: The Antebellum Era………………………………………………………….22 Chapter 2: Secession and the Civil War…………………………………………………66 Chapter 3: Reconstruction and the Post-War Years……………………………………112 Epilogue………………………………………………………………………………...150 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………154 ii Abstract The following explores how Frederick Douglass used memoires of the Haitian Revolution in various public forums throughout the nineteenth century. Specifically, it analyzes both how Douglass articulated specific public memories of the Haitian Revolution and why his articulations changed over time. Additional context is added to the present analysis as Douglass’ various articulations are also compared to those of other individuals who were expressing their memories at the same time. -

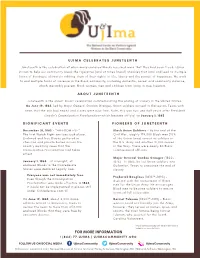

Juneteenth One-Sheeter

U J I M A C E L E B R A T E S J U N E T E E N T H Juneteenth is the celebration of when many enslaved Blacks received word that they had been freed. Ujima strives to help our community break the figurative (and at times literal) shackles that bind and lead to multiple forms of bondage; ultimately robbing them of their rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We work to end multiple forms of violence in the Black community, including domestic, sexual and community violence, which inevitably prevent Black women, men and children from living in true freedom. A B O U T J U N E T E E N T H Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration commemorating the ending of slavery in the United States. On June 19, 1865, led by Major General Gordan Granger, Union soldiers arrived to Galveston, Texas with news that the war had ended and slaves were now free. Note, this was two and half years after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation—which became official on January 1, 1863. S I G N I F I C A N T E V E N T S P I O N E E R S O F J U N E T E E N T H December 31, 1862 - "FREEDOM EVE" Black Union Soldiers - By the end of the The first Watch Night services took place. Civil War, roughly 179,000 Black men (10% Enslaved and free Blacks gathered in of the Union Army) served as soldiers in churches and private homes across the the U.S.